Summary

| Action of 22 August 1917 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Battle of Ypres of the First World War | |||||||

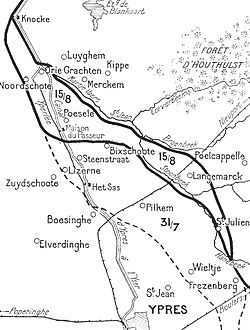

Front line after Battle of Langemarck, 16–18 August 1917 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sir Douglas Haig Hubert Gough |

Crown Prince Rupprecht Sixt von Armin | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

14th (Light) Division 15th (Scottish) Division 61st (2nd South Midland) Division 18th (Eastern) Division 11th (Northern) Division Tank Corps | Gruppe Ypern | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6 brigades, 18 tanks | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,508 (excl. XVIII Corps) | |||||||

class=notpageimage| St Julien, in West Flanders | |||||||

The action of 22 August 1917, took place during the First World War, in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front as part of the Third Battle of Ypres. The engagement was fought by the Fifth Army (General [[Hubert Gough) of the British Expeditionary Force and the German 4th Army (Lieutenant-GeneralSixt von Armin). During the Battle of Langemarck (16–18 August), the British had advanced north of the village but had been defeated further south and failed to capture the Wilhelmstellung, the third German defensive position. At a conference with the Fifth Army corps commanders on 17 August, Gough arranged for local attacks to gain jumping-off positions for another general attack on 25 August. At the action of the Cockcroft on 19 August, XVIII Corps and the 1st Tank Brigade had captured five fortified farms and strongpoints for a fraction of the casualties of a conventional attack.

The attack on 22 August was much bigger effort, which advanced the British front line up to 600 yd (550 m) in places, on a 2 mi (3.2 km) front but failed to reach the more distant objectives. On 24 August, a German Gegenangriff (methodical counter-attack) recaptured Inverness Copse on the Gheluvelt Plateau and the more ambitious British attack due on 25 August was cancelled. It began to rain on 23 August and torrential rain fell on 26 August, flooding the battlefield again. Haig transferred responsibility for the offensive to General Herbert Plumer and the Second Army, to include the southern edge of the Gheluvelt Plateau in the offensive. As reinforcements were transferred from the armies further south, the Fifth Army continued with minor operations. On 27 August, the Springfield and Vancouver blockhouses were captured by tanks supported by infantry from the 48th (South Midland) Division but most attacks were costly failures. The quantity of casualties and the cold, wet and muddy conditions lowered morale among the infantry on both sides.

Background edit

German defensive tactics edit

In July 1917, the 4th Army defence in depth began with a front system of three breastworks Ia, Ib and Ic, about 200 yd (180 m) apart, garrisoned by the four companies of each front battalion, with listening-posts in no-man's-land. About 2,000 yd (1,800 m) behind was the Albrechtstellung (second or artillery protective line), the rear boundary of the forward battle zone (Kampffeld). About 25 per cent of the infantry in the supporting battalions were Sicherheitsbesatzungen (security detachments) to hold strong-points, the remainder being Stoßtruppen (storm troops) to counter-attack towards them from the back of the Kampffeld.[1]

Dispersed in front of the line were divisional Scharfschützen (machine-gun armed sharpshooters) in the Stützpunktlinie (strongpoint line) a line of pillboxes, blockhouses and fortified farms prepared for all-round defence. The Albrechtstellung also marked the front of the main battle zone (Grosskampffeld) which was about 2,000 yd (1,800 m) deep, containing most of the field artillery of the Stellungsdivisionen (ground holding divisions) behind which was the Wilhelmstellung. In the pillboxes of the Wilhelmstellung were reserve battalions of the front-line regiments, held back as divisional reserves.[2]

Battle of Langemarck edit

At the Battle of Langemarck, (16–18 August), XVIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Ivor Maxse) had attacked at 4:45 a.m. with a brigade each from the 48th (South Midland) Division and the 11th (Northern) Division, supported by eight tanks. The tanks were ordered to keep off the roads but the approach to the front line was so boggy that the tanks were cancelled and sent back. The 48th (South Midland) Division attacked with one brigade and after a long fight managed to capture the last house at the north end of St Julien, taking forty prisoners and a machine-gun. The advance resumed and as the first wave went over a rise 200 yd (180 m) east of the Steenbeek, it was caught in cross fire from Hillock Farm and Maison du Hibou 200 yd (180 m) beyond. Border House and the gun pits either side of the north-east bearing St Julien–Winnipeg road were captured but attempts to press on were bloodily repulsed and parties that reached Springfield Farm disappeared.[3]

The 48th (South Midland) Division consolidated on a line from the village to the gun pits, Jew Hill and Border House. At 9:00 a.m., German troops massed around Triangle Farm and made an abortive counter-attack at 10:00 a.m. Another counter-attack after dark was repulsed at the gun pits and at 9:30 p.m., a counter-attack from Triangle Farm was repulsed. The Germans in Maison du Hibou and Triangle Farm, opposite the 48th (South Midland) Division, caught the troops on the right of the 34th Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division in enfilade as it was fired on from pillboxes to the front. The British captured Haanixbeer Farm and the cemetery but lost the barrage and were unable to capture the Cockcroft and Bülow Farm. On the left, the brigade dug in 100 yd (91 m) north-east of Langemarck, opposite the White House and Pheasant Farm and on the right facing Maison du Hibou and Triangle Farm to the east. With observation from higher ground, German artillery-fire inflicted many casualties on the British troops holding the new line beyond Langemarck.[4]

Fifth Army edit

After the Battle of Langemark, Major-General Oliver Nugent, commander of the 36th (Ulster) Division, reported that German artillery could not bombard advancing British troops once they were inside the German forward zone, where the German positions were lightly held and distributed in depth. The advance of British troops following-up had been much easier to obstruct by bombarding no man's land but helping the foremost British infantry was more important than counter-battery fire, even if it had failed to suppress the German guns. Nugent wanted fewer field guns in the creeping barrage and the surplus to fire sweeping (side-to-side) barrages. Shrapnel shells should be fuzed to burst higher up, to hit the inside of shell holes where German troops took cover and creeping barrages should be slower, with more and longer pauses, during which the barrages from field artillery and 60-pounder guns should sweep and search (fire from side-to-side and back-and-forth). The infantry should change formation from skirmish lines to company columns accompanied by a machine-gun and a Stokes mortar. The advance should be on a narrower front, since skirmish lines were impractical in muddy crater fields and broke up under machine-gun fire.[5]

Tanks to help capture pillboxes had bogged down behind the British front-line and air support had been impeded by the weather, particularly by low cloud early on and a lack of aircraft for battlefield support. One aircraft per corps had been reserved for counter-attack patrols and two aircraft per division for ground attack. Only eight aircraft had been available to cover the army front and engage German counter-attacks.[6] Signals had failed at vital moments and deprived the infantry of artillery support, making German counter-attacks much more effective in areas where the topography gave German artillery observers sight of the British infantry. The 56th (1/1st London) Division report recommended that the depth of the advance be shortened to give more time for consolidation and to minimise the organisational and communication difficulties being caused by the muddy ground and wet weather.[7] Artillery commanders asked for two aircraft per division exclusively for counter-attack patrols.[8]

Prelude edit

British preparations edit

At the Battle of Langemarck, XIV Corps and the French I Corps in the north had overrun the Wilhelmstellung and XVIII Corps, to their right, captured Langemarck and a short stretch of the Wilhelmstellung east of the village. On the rest of the corps front and on the XIX Corps and II Corps fronts further south, most captured ground had been lost to German counter-attacks.[9] Dispersed German strong points, fortified farms and pillboxes in the Grosskampfzone (main battle zone), the area between the Albrechtstellung and the Wilhemstellung, were greater in number than in the Kampgzone (battle zone) between the original front line and the Wilhemstellung. German artillery had concentrated on cutting off the leading British troops from their supports by bombarding the British front line and its approach routes, causing casualties and delays to the delivery of supplies and troops following up the advance.[10]

German machine-gunners in their strong points, pillboxes and fortified farms had severely depleted the British infantry as they advanced, even though German artillery could not bombard the area for fear of hitting their infantry. Once the II Corps attack on the Gheluvelt Plateau had been repulsed, the defenders were free to fire on the British in the Steenbeek valley north of the Ypres–Roulers railway, sweeping them with machine-gun fire in enfilade from their right (southern) flank.[11] On 17 August, the fresh 15th (Scottish) Division and the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division (the second line Territorial Force duplicate of the 48th [South Midland] Division) relieved the 16th (Irish) Division and the 36th (Ulster) Division in the XIX Corps area. In the XVIII Corps area further north, the 48th (South Midland) Division (Major-General Robert Fanshawe) had been in the line since 4 August and the 11th (Northern) Division (Major-General Henry Davies) since 7 August but had to remain.[12] North of the Ypres–Roulers railway, five days of preparatory artillery-fire and constant patrolling had established the positions of some of the defenders but on 21 August, an attack on Borry House was stopped by German small-arms fire, about 50 yd (46 m) short of the objective.[13]

Fifth Army plan edit

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0.0 | 68 | dull |

| 17 | 0.0 | 72 | fine |

| 18 | 0.0 | 74 | fine |

| 19 | 0.0 | 69 | dull |

| 20 | 0.0 | 71 | dull |

| 21 | 0.0 | 72 | fine |

| 22 | 0.0 | 78 | dull |

| 23 | 1.4 | 74 | dull |

At a conference with the Fifth Army corps commanders on 17 August, Gough complained that troops had failed to hold captured ground and considered court-martialling some NCOs and officers to make examples. Gough also thought that divisions had been relieved too frequently, which had exhausted fresh divisions before the attack.[16] Where divisions had fallen short on 16 August, the corps commanders were asked for proposals for attacks to reach the final objective. Lieutenant-General Claud Jacob (II Corps) wanted to attack the brown line and then the yellow line, Lieutenant-General Herbert Watts (XIX Corps) wanted to attack the purple line but Maxse (XVIII Corps) preferred to attack the dotted purple line, ready to capture the yellow line at the same time as XIX Corps. The proposed attacks on the plethora of "lines" marked on staff maps were intended to reach good jumping off points for a much larger attack on the Wilhemstellung by II, XIX and XVIII corps on 25 August but attacking in different places, at different times, risked defeat in detail.[17]

In June, the 1st Tank Brigade had been allotted to XVIII Corps, the 3rd Tank Brigade to XlX Corps and the 2nd Tank Brigade to II Corps.[18] The Action of the Cockcroft, a small, surprise attack by XVIII Corps and twelve tanks 1st Tank Brigade on 19 August succeeded but for the bigger effort on 22 August, the artillery would have to suppress the German artillery and machine-gunners on a much wider front, if the infantry were to struggle through the mud and waterlogged shell-holes to their objectives. On 19 August, a British intelligence estimate reported 558 German guns around the Ypres salient, which meant that the Fifth Army had a 3:1 advantage but the British guns were firing outwards on a 15,500 yd (8.8 mi; 14.2 km) front, which diluted their effect.[19] The XVIII Corps divisions were to advance to the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road and XIX Corps was to get across the morass of the Hanebeek stream and capture the Potsdam, Vampir, Borry Farm, Iberian Farm, Pommern and Bremen redoubts, Gallipoli Farm and Somme Farm, to advance up Frezenberg Ridge closer to the Wilhemstellung.[20]

An overhead machine-gun barrage was to be fired and six platoons of pioneers were to consolidate new positions on Hill 35. On the five days before the attack, night harassing fire from artillery and machine-guns was conducted; field artillery and heavy artillery bombarded all known strong points and patrols covered the front, looking for German positions. To guard the right flank of the 15th (Scottish) Division, II Corps to the south was to provide smoke barrages and covering fire from artillery and machine-guns. The 47th (1/2nd London) Division on the northern flank of II Corps, was to set up posts along the Ypres–Roulers railway line between Railway Dump and Potsdam.[20] On 21 August, a patrol reached Beck House and bombed it, then a party was sent to occupy the post but was forestalled by the Germans and had to occupy a trench 50 yd (46 m) short.[21]

German defences edit

On 31 July, the German front line north of the Ypres–Roulers railway and the Kampffeld had been overrun and the garrisons lost. The front line had been pushed back between the Albrechtstellung and the Wilhelmstellung, behind which was the rearward battle zone (rückwärtiges Kampffeld). The main defensive engagement had been fought in the Grosskampffeld by the reserve regiments and Eingreif divisions, against depleted, tired and disorientated attackers, whose advance had been slowed by the forward garrisons before they were overrun. The new German front was a line of shell holes backed by the fortified farms, strong points and pillboxes in the Grosskampffeld in front of the Wilhelmstellung.[22] On 16 August, the British had tried to capture the Wilhemstellung but in the XVIII Corps area, the British artillery failed to destroy many pillboxes and fortified farms in the Grosskampffeld or to suppress the German artillery, which inflicted 81 per cent of the wounds suffered by the infantry of the 11th (Northern) Division.[23]

The 11th (Northern) Division had captured most of its objectives but the 48th (South Midland) Division on the right barely advanced 100 yd (91 m).[23] After 16 August, the Germans increased the size of regimental sectors to enable even more dispersal and divided the field artillery, one part to be kept hidden and used only against big attacks.[24] The Germans occupied the higher ground and their observation posts could direct the fire of the artillery with greater accuracy than the British observers, who were on the wrong side of the spurs running northwards from the Gheluvelt Plateau. German artillery was concealed by the plateau ridges around the salient, the guns could fire inwards, concentrating their firepower. Dummy positions had been built to evade British counter-battery fire and British reconnaissance aircraft were grounded by bad weather; the muffling effect of the high ground made British sound-ranging much less effective.[25]

Battle edit

XIX Corps edit

In the 15th (Scottish) Division area, supported by patrols from the 47th (1/2nd London) Division south of the Ypres–Roulers railway, the 45th Brigade on the right was to attack behind four tanks, a creeping barrage and overhead fire from 32 machine-guns but the tanks ditched short of the front line on the Frezenberg–Zonnebeke road.[26] As soon as the infantry advance began, German artillery-fire fell along a line from Frezenberg to Square Farm, followed by machine-gun fire on the attacking troops and on the support and reserve troops even before they left their trenches. The 13th Battalion, Royal Scots (13th RS) and the 11th Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (11th ASH) were supported by the 6th Battalion, Cameron Highlanders (6th Cameron). As soon as the advance began, German small-arms fire became so dense that runners could not go back or reinforcements move forward. Recognition flares were seen later at Potsdam, Borry Farm and Vampir Farm but nothing else was known of the progress of the infantry. Survivors retreated to join the 6th Cameron along the track running north-west from the Railway Dump to Beck House.[27]

On the left flank, the 8th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders (8th Seaforth) and the 7th Cameron of the 44th Brigade were to be preceded by six tanks but four bogged on the start line west of Pommern Redoubt. The infantry were caught by machine-gun fire on the start line and on the right some parties confused the Steenbeek with the Zonnebeke stream and lost direction. It was thought that the right company, that advanced east of Beck House, was caught by machine-gun fire from behind and annihilated. The advance of the left company of the 8th Seaforth was costly but got to within 40 yd (37 m) of Iberian Farm. The support company went forward to reinforce by rushes, from shell-hole to shell-hole, reaching the forward company despite many casualties and linked with the 7th Cameron on the left. The 7th Cameron had reached the crest of Hill 35, where the advance was stopped by machine-gun fire from Gallipoli and the troops dug in. Iberian Farm had not been captured by the 8th Seaforth and the machine-gunners in the blockhouse fired on the 7th Cameron troops on Hill 35. The 8th Seaforth made several attempts to outflank Gallipoli, all of which failed. To the left of the 7th Cameron, the six pioneer platoons detailed to consolidate Hill 35 had advanced via Pommern Redoubt and then began to dig a defensive flank north-east from Pommern to Hill 35, then north-west to Somme Farm; as the trenches were dug, fewer casualties were suffered.[28]

By 7;00 a.m. it was clear that the 15th (Scottish) Division attack had failed; the line was only a few yards forward on the right and in the centre and the few survivors of the attack were back on the start line. At 8:00 a.m. the troops on the right flank of the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division began to fall back until rallied on a line dug slightly north of Somme Farm. On the right flank, the 13th RS made several attempts to get forward by shell-hole rushes but found it impossible against the massed machine-gun fire from the German fortifications.[29] Two small German counter-attacks from 1:00 to 3:00 p.m. were driven off with help from the 47th (1/2nd London) Division to the south and German small-arms fire was eventually subdued by constant rifle and Lewis-gun fire.[30] During the evening, reports were received of troops near Beck House, Borry Farm, Iberian Farm and Gallipoli and orders were issued to rush the positions in the dark. The attacks failed against alert opposition but the line was advanced about 80 yd (73 m) towards Gallipoli, until cross fire stopped the advance and the new position was consolidated.[29][b]

The 184th Brigade of the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division attacked with the 2/1st Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (2/1st OBLI) and the 2/4th OBLI, supported by the 2/5th Gloucestershire Regiment (2/5th Gloucester). The 2/4th OBLI eventually managed to capture Pond Farm, after the garrison of fifty men surrendered in the afternoon, then the battalion pushed on and captured Hindu Cot. The 2/1st OBLI advanced on Kansas Cross but the supporting companies had many casualties capturing Aisne and Somme farms. Aisne Farm was re-captured during a German counter-attack and the 2/5th Gloucester came up from reserve to reinforce the new line, which had been advanced about 600 yd (550 m) in places.[32] On 24 August, attacks on Aisne Farm and Schuler Galleries failed.[31]

XVIII Corps edit

The 143rd and 144th brigades of the 48th (1st South Midland) Division were to attack with an advance guard of tanks followed by a thin wave of infantry to mop up German positions and capture the St Julien–Polcappelle road. On the right flank, a protective barrage began at 4:45 a.m. and ten tanks drove out of St Julien. Six tanks advanced eastwards up the road to Winnipeg followed by the 1/5th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment (1/5th Warwick) but the tanks were knocked out or bogged at Janet Farm. Four tanks drove along the St Julien–Polcappelle road and enabled the 1/5th Warwick to capture the Springfield strong point (recaptured in a German counter-attack). The infantry attacked gun pits and captured Winnipeg further on, lost Winnipeg to a counter-attack, then recaptured it but the German artillery and machine-guns prevented the British infantry in support from getting forward to reinforce the attacking troops. On the left flank, the 1/6th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment (1/6th Gloucester) of the 144th Brigade managed to advance close to the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road in touch with the 1/5th Warwick; the tanks on the St Julien–Polcappelle road attacked Vancouver, which was captured at 8:15 a.m.[12] By nightfall, Jury Farm and Springfield had been captured and then lost to counter-attacks, the gun pits were thought to be occupied but Vancouver, Spot Farm and Pond Farm were still held by the Germans. During the night a fresh battalion moved up but the division had managed to advance scattered outposts no more than 200 yd (180 m) beyond the start line.[33]

On the left (northern) flank, the 11th (Northern) Division attacked with the 6th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment (6th Lincoln) and the 6th Battalion, Border Regiment (6th Border) of the 33rd Brigade, to reach the White House and join the 38th (Welsh) Division on the right flank of XIV Corps in the Wilhemstellung. On the right flank, two tanks were to lead an advance of 2,500 yd (2,300 m) to attack Bülow Farm, the most distant of the XVIII Corps objectives. The tanks followed the creeping barrage out of St Julien on the Poelcappelle road followed by the 6th Lincoln and drove to the Vancouver blockhouse. The tank crews found that the Germans had cut down the trees lining the road and managed to drive over the obstacles, machine-gunning as they went, to find that the 6th Lincoln had already arrived, begun their attack and been pinned down by machine-gun fire from Bülow Farm. The first tank was hit by a shell and blocked most of the road but the second tank managed to drive round and attack the farm, which was captured. The 6th Lincoln formed a defensive flank through Keerselare along the St Julien–Poelcappelle road, to link with the 48th (1st south Midland) Division and on the left flank, the 6th Border managed to keep up with the barrage and reach the final objective, gaining touch with the 38th (Welsh) Division in the XIX Corps area, close to the White House.[34]

II Corps edit

At 7:00 a.m. the 43rd Brigade of the 14th (Light) Division on the Gheluvelt Plateau, attacked Inverness Copse and the open ground to the north. One battalion got into Inverness Copse south of the Menin road with few losses and defeated the 5th Company of II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 67 (IR 67). At about 8:00 a.m. the château south of the road was captured and 60 prisoners taken. The companies of IR 67 were almost obliterated in the fighting but reduced the British party to about 90 men. The advance of the second battalion was caught in machine-gun fire from Inverness Copse, lost the barrage and was forced under cover. Three of the supporting tanks bogged down but the fourth forced the Germans from Inverness Copse and the second battalion managed to move up another 200 yd (180 m) but was still far short of the objective.[35] IR 67 sent the I Battalion to counter-attack, which found the survivors of II Battalion in the Albrechtstellung and took them forward. The British infantry were too depleted to repulse the attack and fell back to the western edge of the Copse. Reinforced by a fresh battalion, the British managed to hold a line about 250 yd (230 m) south of the Menin road and gained touch with the battalion to the north. At around 5:00 p.m., two companies of III Battalion, IR 67 in the Albrechtstellung advanced into the Copse but a counter-attack had to be postponed.[36]

Tank operations edit

A tank company of D Battalion attacked Springfield and Winnipeg using the same tactics as the attack on 19 August but the ploy failed and the accompanying infantry were pinned down. Further south as far as the Gheluvelt Plateau, tanks from the 2nd and 3rd Tank brigades also attacked but to little effect. On the XIX Corps front, a tank of F Battalion, 3rd Tank Brigade drove south-east of St Julien towards Gallipoli but the accompanying infantry were driven under cover and the tank ditched in no man's land. The tank was so far forward that the infantry thought that it had been captured and opened fire on it as German troops did the same. The crew were stranded, because of the British small-arms fire but with their 6-pounders and machine-guns, managed to repulse several German parties from the troops assembling behind Gallipoli to counter-attack the British infantry. After dark, German infantry set up a machine-gun close to the tank and got on the roof; the British infantry, assuming that the Germans had turned the tank into a strong point, continued to fire on it.[37]

On the morning of 23 August, attempts by the crew tried to signal to the British lines failed and the crew fought on. On the night of 23/24 August, the Germans attacked again, using machine-guns and hand grenades but were driven off. By dawn on 24 August, one crewman was dead, all but the commander were wounded and little food or ammunition was left. Every attempt to communicate with the British infantry failed; when night fell a crew member managed to crawl back and got the British to cease fire; the rest of the crew then made their escape, having spent 72 hours in action.[37] Gallipoli was engaged with a 6-pounder in the tank Fray Bentos until it bogged down and the infantry began to retire. The crew of Fray Bentos continued to fire as German troops closed in. The tank was hit by small-arms fire from both sides and all of the crew were wounded. At 9:00 p.m. the crew abandoned the tank, handed the guns to the infantry nearby and made their way back.[26]

Aftermath edit

Analysis edit

Gough had received an intelligence report on 24 August describing the checkerboard layout of the German defensive positions and the tactic of holding back counter-attacking Eingreifdivisionen beyond artillery range. Gough ordered that more troops be used to ensure that enough would survive to defeat counter-attacks and that the ratio of troops reserved for mopping up behind the foremost infantry should be increased, to make sure that by-passed positions were occupied.[38] In 1931, Gough wrote that the attack had been made with reduced objectives because of the state of the ground to limit the ordeal of the infantry, while conforming to his instructions from Haig to continue the battle. An advance of about 500 yd (460 m) had been achieved on about a 2 mi (3.2 km) front up to the II Corps boundary. The attack by II Corps on the Gheluvelt Plateau was a success but by 24 August, German counter-attacks had re-taken most of the captured ground.[39] In 1948, James Edmonds, the British official historian, wrote that the XIX and XVIII Corps were still overlooked by the German defenders in the Wilhelmstellung from the Ypres–Zonnebeke road northwards to the east end of Langemarck.[40] In 1996, Prior and Wilson wrote that the success of XVIII Corps on 19 August had not been repeated in the bigger effort on 22 August. The German strong points were further from the roads still fit to drive on; when the tanks tried to get closer they sank in the mud.[41]

On the XIX Corps front, machine-gun fire from the German fortified posts had devastated the infantry of the 15th (Scottish) Division and 61st (2nd South Midland) Division as they struggled through the mud. A report from the 8th Seaforth described how the creeping barrage had failed to damage many pillboxes; the German defences had been underestimated and were insufficiently bombarded by the heavy artillery. The swiftness of the Germans in inflicting casualties left the survivors incapable of capturing strong points, even where the garrisons seemed willing to surrender. The attack by II Corps on Inverness Copse began two hours later, which gave the Germans on the Gheluvelt Plateau time to get ready.[41] In 2008, J. P. Harris called the attack an "almost complete failure" and that rather than pausing, Gough continued to attack until 27 August, despite it raining from 23 August.[42] In 2017, Nick Lloyd wrote that the attack had gained some ground but that the German pillboxes, blockhouses and fortified farms had been almost impossible to capture. Eighteen tanks were still operational and four tanks from C Battalion managed to drive along the Frezenberg–Zonnebeke road but it had been bombarded to the point where it was almost invisible. One tank had been knocked out and the others ditched. Six tanks of F Battalion had been able to suppress snipers and some machine-gunners but it had not been a successful operation for the Tank Corps.[43]

After the Germans recaptured Inverness Copse on 24 August, Gough cancelled the general attack due for 25 August. Haig transferred responsibility for the offensive to the Second Army, which would use all the resources that could be assembled to capture the Gheluvelt Plateau. The II Corps was to revert to the Second Army and the attack front was extended southwards to Klein Zillebeke.[44] By the end of August, thirty German divisions had fought at Ypres, two of them twice and 23 had been exhausted and replaced; at full strength, German divisions had only 12,000 men, rather than the 20,000, in a British division. The British had used 21 divisions, two twice, of which 14 had been withdrawn. Including the four French divisions of the First Army, 26 Anglo-French divisions with an establishment of 520,000 men had engaged 37 German divisions with an establishment of 440,000 men. Nine of the German divisions had been transferred from Champagne and Alsace-Lorraine, which eased the pressure on the French armies.[25]

It was conventionally assumed that an attacker needed a 3:1 superiority to prevail but the Fifth Army had a superiority of only about 2:1.2; the British would have needed another 40 divisions to outnumber the Germans by 3:1.[25] In 2007, Jack Sheldon wrote that during August the 4th Army inflicted "morale-sapping" defeats on the British and that after the attack on 22 August, British prisoners complained about their commanders and said that Germany could not be defeated without the Americans. Despite the undoubted success of the defence, the victories in August had been costly and had been the cause only of grim satisfaction to the German commanders.[45] Doubts among the divisional staffs about the competence of Gough and the Fifth Army staff increased and relations were further strained by what was perceived as the abrasiveness of the chief of staff, Major-General Neill Malcolm but these complaints may have been influenced by personal considerations. Major-General Gerald Cuthbert (39th Division) was sacked on 20 August and Major-General Hew Fanshawe (58th (2/1st London) Division) was sent home on 6 October. The officers challenged their dismissals by Maxse but Gough upheld the decisions. Major-General George Harper (51st Highland Division) received a "glowing report" from Maxse and was promoted to corps command; the 48th (South Midland) Division commander, Major-General Robert Fanshawe (brother of Hew), received a favourable report and these matters might have coloured judgements made on Gough and the Fifth Army staff.[46]

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 0.1 | 68 | cloud |

| 25 | 0.0 | 67 | cloud |

| 26 | 19.6 | 70 | dull |

| 27 | 15.3 | 57 | — |

On 19 August, Sir Douglas Haig suggested that victory was possible in 1917 and ordered rear areas to be scoured for men capable of joining the infantry. Despite Haig's "endemic optimism", control of the battle was transferred to the Second Army (General Herbert Plumer) from 24 August, to capture the Gheluvelt Plateau, in a wider front attack to overcome its elaborate defences and counter-attack divisions, which were making the progress of the Fifth Army further north irrelevant.[48] In 2014, Robert Perry wrote that the success of the German defence had been likely, given the resources available to the Fifth Army; its achievements had been gained by resilience of the infantry, which had been exhausted. The 4th Army had also been severely shaken and its troops worn out. More German divisions were on the way to Flanders, denying the Germans the initiative and aiding the French recovery from the trauma of the Nivelle Offensive in the spring. The Fifth Army was far from defeat and it had inflicted a "severe mauling" on the 4th Army.[25]

Tanks edit

The initial estimate that one tank in two would get into action was revised to one tank in ten but those that did engage the Germans usually had considerable, if local, effect. On 22 August, four tanks attacking with II Corps on the Gheluvelt Plateau had some effect and in the XIX Corps area, 18 tanks were used in a gamble that they would find a way forward, despite the Zonnebeke–Frezenberg road having been obliterated by artillery-fire. Tanks of the 1st Brigade attacked Winnipeg, Vancouver, Bülow Farm and other pillboxes in the XVIII Corps area and several tanks lasted long enough to assist the infantry. Where tanks got into action, the psychological effect led some Germans to surrender as soon as they appeared; some prisoners said that they "felt helpless" against the tanks. Four tanks of the 2nd Brigade were to attack Inverness Copse in the II Corps area on 23 August but the operation was rushed, liaison broke down and the attack failed. On 26 August, another four tanks with II Corps attacked Jerk House; the morning was misty, German shells set off a dump of smoke bombs and the attack failed. There was a downpour in the night and four tanks due to support an attack on 27 August failed to reach the start line.[49] In Tanks in the Great War, 1914–1918 (1920) J. F. C. Fuller wrote that on 22 August, a tank [Fray Bentos] ditched near Gallipoli, held out for sixty-eight hours and repulsed several counter-attacks in the vicinity, until the crew withdrew on the night of 24/25 August.[50]

Casualties edit

In the History of the Great War the official historian, James Edmonds, wrote that the 15th (Scottish) Division had 2,071 casualties, 1,052 casualties in the 44th Brigade and 1,019 in the 45th Brigade, the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division lost 914 men in the attack and during German counter-attacks on 23 August. From 22 to 24 August, the 43rd Brigade, 14th (Light) Division had 1,523 casualties.[40] Prior and Wilson wrote in 1996 that in the XVIII and XIX corps attacks, the British suffered 3,000 casualties.[38] In 2014, Robert Perry reproduced the figures from the Official History.[12]

Minor Actions edit

23–26 August edit

Despite the failures on 22 August, the beginning of another rainy spell on 23 August and 0.77 in (19.6 mm) of rain on 26 August, the offensive continued.[38][51] On 24 August, a German party with flamethrowers recaptured the gun pits occupied by the 48th (South Midland) Division during the 22 August attack. When a company of the 8th Warwick counter-attacked next day, the pits were discovered to be unoccupied. During the lull, the 48th (South Midland) Division dug assembly positions sufficient for four battalions, only for the camouflage material to hide them to be destroyed when German artillery hit the supply dump at van Heule Farm.[33]

At 11:00 p.m. on 25 August, two companies of the 15th (Scottish) Division attacked Gallipoli and Iberian farms, advanced behind a creeping barrage and a Stokes mortar bombardment. The Scottish reached Gallipoli, only to be shot down from behind by a hidden machine-gun and then be caught in crossfire from the farm buildings and a derelict tank. The survivors fell back and dug in on a line 170 yd (160 m) forward of the start line; during the attack, a patrol towards Iberian Farm was also repulsed.[31] A 61st (2nd South Midland) Division attack on Aisne Farm failed.[52]

Action of 27 August edit

On 27 August, the Fifth Army attacked again, II Corps on the right attacking at 4:45 a.m. and the corps to the north at 1:55 p.m. The attacking battalions had moved up during the night in rain and then had to remain hidden for ten hours, soaking wet and in mud up to their knees. Twenty minutes before zero hour, torrents of rain fell and a gale began to blow.[53] Each man carried three smoke candles to form a smoke screen but these were soaked by the rain; the ground was covered in waterlogged shell-holes and became much muddier, causing to the infantry to lag behind the creeping barrage.[53] In the XIX Corps attack, the 15th (Scottish) Division advanced with 120 men, who were forced back after reaching Gallipoli.[54] The 61st (2nd South Midland) Division attack was stopped about 100 yd (91 m) short of Schuler Farm. After losing about a third of the men and half of their officers, the survivors fell back to the start line. In the XVIII Corps area, the 48th (South Midland) Division was to advance 800 yd (730 m) with the 143rd Brigade on the right flank and the 144th Brigade on the left. The first objective of the 143rd Brigade was the trench from Winnipeg to Springfield and after a thirty-minute pause the brigade was to advance to a second objective, the south end of the Wilhemstellung. On the left, the 144th Brigade was to capture the Wilhemstellung as far south as the Genoa blockhouse.[55]

The creeping barrage and the overhead barrage by 64 machine-guns would lift twelve minutes after H-Hour and move at 100 yd (91 m) in twelve minutes, then accelerate to a rate of 100 yd (91 m) every eight minutes. The higher ground beyond was to be bombarded by smoke shell, shrapnel and gas for three hours. The attack was to be accompanied by four tanks of the 1st Tank Battalion, to cover the advance to the final objective; the 145th Brigade, which was to reach the jumping-off trenches of the other two brigades by zero hour + 4, was to leapfrog the leading brigades to the final objectives at von Tirpitz, Stroppe and Hubner farms at zero hour + 5.[56][55] On the left of the 143rd Brigade, Springfield was the first objective of three companies of the 1/8th Warwick, supported by two companies of the 1/7th Warwick of the 144th Brigade to the north. As the rain came down again, the water formed pools in stretches up to 30 yd (27 m) wide. Four tanks drove up the road towards the Triangle and some troops reached the gun pits but two of the tanks bogged down beyond Hillock Farm.[57]

Some of the German troops in the front line appeared to have been surprised by the barrage and several of the dead were seen to be without boots.[58][d] Some of the survivors appeared willing to surrender but as the Worcester battalions struggled slowly through the mud, the Germans resumed firing at close range. C Company of the 1/8th Warwick was ordered to up the road to Springfield and only about 15 unwounded men advanced. In the rain and gathering darkness, German return fire was inaccurate until the party reached the bogged tanks. Amidst shrapnel-fire, the party struggled on and when the survivors reached the Triangle, they found that the German small-arms fire was going over their heads and the artillery-fire had died down. Wounded from the 1/8th Worcester and 1/7th Warwick, in shell-holes nearby, joined the party and a tank drove behind the Springfield blockhouse, only to be knocked out soon after it opened fire. As the party got closer, in the darkness, a group which turned out to be from the 1/7th Warwick, attacked from the opposite side. The German garrison ran out and 16 prisoners were taken but they had only moved about 100 yd (91 m) towards the rear when they were hit by German machine-gun fire.[59]

After a quick conference, the British decided that Spot Farm and the cemetery were too formidable to attack and dug in on a line from east of the blockhouse to 100 yd (91 m) west of the Langemarck–Zonnebeke road, where troops from the 1/7th Worcester had managed to advance another 300 yd (270 m) and throw back a defensive flank. Springfield was found to be solidly built, with three walls about 10 ft (3.0 m) thick, each with a machine-gun post and the rear wall containing a 3 ft × 3 ft (0.91 m × 0.91 m) opening.[60] The 1/8th Warwick had lost 66 men killed and the rest of the brigade had been stopped short of the first objective.[61] The 11th (Northern) Division on the left was only able to make a small advance near Pheasant Farm.[62] The 38th (Welsh) Division on the right flank of XIV Corps attacked with the 16th (Cardiff City) Battalion, Welch Regiment of the 115th Brigade, which was to advance from White Trench and Bear Trench and capture about 600 yd (550 m) of the Wihlemstellung (Eagle Trench), either side of the Schreiboom crossroads. The infantry had waited in shell holes, which filled with water during the rainstorm, greatly impeding the troops as they climbed out to begin the advance. The Welsh lost the barrage in the mud and received small-arms fire from Pheasant Farm to the front and enfilade fire from the White House on the right flank; by evening the remaining troops were back where they started.[63][e]

Notes edit

- ^ Rainfall measured at Vlamertinghe, temperature at Ypres.[15]

- ^ From 23 to 25 August, the 15th (Scottish} Division front was relatively quiet, Scottish snipers keeping the Germans under cover; the battalions involved in the attack were relieved and the front reorganised.[31]

- ^ Rainfall measured at Vlamertinghe, temperature at Ypres[15]

- ^ The Württemberg 27th, 204th, 26th and 26th Reserve divisions (north to south).[58]

- ^ To reach Springfield and Vancouver on the Langemarck–Zonnebeke road, the tanks had to detour up the St Julien–Poelcappelle road to the Keerselare crossroads, then turn south onto the Langemarck–Zonnebeke road, because the direct route along the St Julien–Winnipeg track was blocked by derelict tanks. The rains had made the road very slippery and German heavy artillery bombarded the road as soon as the tanks appeared. One tank bumped a tree trunk 0.5 mi (0.80 km) from the German front line, slid off the road and bogged. Two crewmen got out under machine-gun fire and attached the un-ditching beam but this only bogged the tank deeper. Three tanks reached the Keerselare crossroads, turned right, passed through British outposts and fired on the Germans sheltering in fortified shell-holes. The effect was limited by banks 4–5 ft (1.2–1.5 m) high on either side; the Germans in shell-holes beyond prevented the British infantry from advancing. One tank drove towards the objectives but was blocked by a knocked-out tank, reversed and slid into a shell crater. The creeping barrage kept going and as the British troops floundered in the mud, German infantry began to advance from shell-hole to shell-hole either side of the tank and the British retired to their old positions. Several hundred yards away, another tank had also put the Germans close by to flight with machine-gun and 6-pounder fire. The tanks were easily visible to German field gunners, who engaged them with direct fire. The crews in the bogged tanks dismounted their Lewis guns and retreated to the road on foot, as the last tank drove about the Keerselare crossroads, trying to find a way through the bogged tanks, until that tank also ditched. Two of the abandoned tanks were hit by shells, one was blown up and the other sank into the mud.[64]

Footnotes edit

- ^ Wynne 1976, p. 292.

- ^ Wynne 1976, p. 288.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, p. 199; McCarthy 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, p. 199; McCarthy 1995, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Falls 1996, pp. 122–124.

- ^ Wise 1981, p. 424.

- ^ Dudley Ward 2001, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, p. 201.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, pp. 189–201.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, pp. 191.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, pp. 194, 201.

- ^ a b c Perry 2014, p. 228.

- ^ Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 181.

- ^ Perry 2014, pp. 203, 230.

- ^ a b Perry 2014, p. 203.

- ^ Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 105.

- ^ Simpson 2006, p. 101.

- ^ Fuller 1920, p. 117.

- ^ Perry 2014, pp. 224–227, 231–232.

- ^ a b Perry 2014, pp. 224–227.

- ^ Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Wynne 1976, pp. 289, 303.

- ^ a b Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 102.

- ^ Wynne 1976, p. 303.

- ^ a b c d Perry 2014, pp. 231–232.

- ^ a b Perry 2014, p. 227.

- ^ Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Stewart & Buchan 2003, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 184.

- ^ Maude 1922, p. 107.

- ^ a b c Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 185.

- ^ Perry 2014, pp. 227–228; Rawson 2017, p. 108.

- ^ a b Mitchinson 2017, p. 174.

- ^ Perry 2014, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Rogers 2011, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Rogers 2011, p. 165.

- ^ a b Browne 1920, pp. 236–238.

- ^ a b c Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Gough 1968, p. 206.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1991, p. 203.

- ^ a b Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Harris 2008, p. 370.

- ^ Lloyd 2017, p. 144.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Sheldon 2007, p. 138.

- ^ Simpson 2006, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Perry 2014, pp. 230, 234.

- ^ Harris 2008, p. 371.

- ^ Williams-Ellis & Williams-Ellis 1919, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Fuller 1920, pp. 117, 123.

- ^ Perry 2014, p. 230.

- ^ McCarthy 1995, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1991, p. 207.

- ^ Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 186.

- ^ a b Mitchinson 2017, p. 175.

- ^ Williams 1999, p. 105.

- ^ Vaughan 1985, pp. 222.

- ^ a b Sheldon 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Vaughan 1985, pp. 222, 224–225.

- ^ Vaughan 1985, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Williams 1999, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Edmonds 1991, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Munby 2003, p. 27; Edmonds 1991, p. 208.

- ^ Watson 1920, pp. 142–147.

References edit

Books

- Browne, D. G. (1920). The Tank in Action (online scan ed.). Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. OCLC 699081445. Retrieved 26 July 2017 – via Archive Foundation.

- Dudley Ward, C. H. (2001) [1921]. The Fifty Sixth Division 1914–1918 (1st London Territorial Division) (Naval and Military Press ed.). London: Murray. ISBN 978-1-84342-111-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II. Nashville, TN: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Falls, C. (1996) [1922]. The History of the 36th (Ulster) Division (Constable ed.). Belfast: McCaw, Stevenson & Orr. ISBN 978-0-09-476630-3. Retrieved 26 July 2017 – via Project Gutenburg.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1920). Tanks in the Great War, 1914–1918. New York: E. P. Dutton. OCLC 559096645. Retrieved 26 July 2017 – via Archive Foundation.

- Gough, H. de la P. (1968) [1931]. The Fifth Army (repr. Cedric Chivers ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 59766599.

- Harris, J. P. (2008). Douglas Haig and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Lloyd, N. (2017). Passchendaele: A New History. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-241-00436-4.

- Maude, A. H. (1922). The 47th (London) Division 1914–1919. London: Amalgamated Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-205-1. Retrieved 26 March 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- McCarthy, C. (1995). The Third Ypres: Passchendaele, the Day-By-Day Account. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-217-5.

- Mitchinson, K. W. (2017). The 48th (South Midland) Division 1908–1919 (hbk. ed.). Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-911512-54-7.

- Munby, J. E., ed. (2003) [1920]. A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division: By the GSO's.I of the Division (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Hugh Rees. ISBN 978-1-84342-583-0.

- Perry, R. A. (2014). To Play a Giant's Part: The Role of the British Army at Passchendaele. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-78331-146-0.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (1996). Passchendaele: the Untold Story. London: Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-07227-3.

- Rawson, A. (2017). The Passchendaele Campaign 1917. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-52670-400-9.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2011). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-90603-376-7.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. London: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-564-4.

- Simpson, A. (2006). Directing Operations: British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-292-7.

- Stewart, J.; Buchan, J. (2003) [1926]. The Fifteenth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (pbk. repr. Naval & Military Press ed.). Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood and Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-639-4.

- Vaughan, E. C. (1985) [1981]. Some Desperate Glory: The Diary of a Young Officer, 1917 (pbk. Papermac ed.). London: Frederick Warne. ISBN 978-0-333-38727-6.

- Watson, W. H. L. (1920). A Company of Tanks. Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood. OCLC 262463695. Retrieved 27 July 2017 – via Archive Foundation.

- Williams-Ellis, A.; Williams-Ellis, C. (1919). The Tank Corps. New York: G. H. Doran. OCLC 317257337. Retrieved 26 July 2017 – via Archive Foundation.

- Wise, S. F. (1981). Canadian Airmen and the First World War. The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Vol. I. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-2379-7.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, Westport, CT ed.). Cambridge: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Theses

- Williams, R. D. (1999). A Social and Military History of the 1/8th Battalion, The Royal Warwickshire Regiment in the Great War (PDF) (MPhil). School of Historical Studies, Birmingham University. OCLC 690660403. Docket no docket. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

Further reading edit

Books

- Cruttwell, C. R. M. F. (1922). The War Service of the 1/4 Royal Berkshire Regiment (T. F.) (online ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 126–128. OCLC 568434340. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Foerster, Wolfgang, ed. (1939). Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die Militärischen Operationen zu Lande Zwölfter Band, Die Kriegführung im Frühjahr 1917 [The World War 1914 to 1918, Military Land Operations Twelfth Volume, Warfare in the Spring of 1917] (in German). Vol. XII (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. OCLC 248903245. Retrieved 29 June 2021 – via Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich.

- Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903–39. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4814-2.

- Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War (1914–1918). Document (United States. War Department) number 905. Washington D.C.: United States Army, American Expeditionary Forces, Intelligence Section. 1920. OCLC 565067054. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Liddle, P. H., ed. (1997). Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third Battle of Ypres. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-588-5.

- Munby, J. E., ed. (1920). A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division: By the GSO's.I of the Division (online ed.). London: Hugh Rees. OCLC 495191912. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

Theses

- Simpson, A. (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18 (pdf). London: London University. OCLC 53564367. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- The 61st (2nd South Midland) Division had the Reputation of Being a poorly Performing Formation. How did it Acquire this Reputation and was it a Justified Description? (PDF) (pdf) (online ed.). Birmingham: University of Birmingham. 984318. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

External links edit

- Tank operations in August 1917