Summary

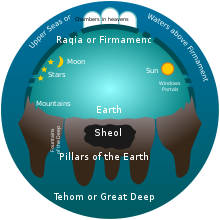

In ancient near eastern cosmology, the firmament signified a cosmic barrier that separated the heavenly waters above from the Earth below.[1] In biblical cosmology, the firmament (Hebrew: רָקִ֫יעַ rāqīa) is the vast solid dome created by God during the Genesis creation narrative to divide the primal sea into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear.[2][3]

The concept was adopted into the subsequent Classical/Medieval model of heavenly spheres, but was dropped with advances in astronomy in the 16th and 17th centuries. Today it is known as a synonym for sky or heaven.

Etymology edit

In English, the word "firmament" is recorded as early as 1250, in the Middle English Story of Genesis and Exodus.

It later appeared in the King James Bible. The same word is found in French and German Bible translations, all from Latin firmamentum (a firm object), used in the Vulgate (4th century).[4] This in turn is a calque of the Greek στερέωμᾰ (steréōma), also meaning a solid or firm structure (Greek στερεός = rigid), which appears in the Septuagint, the Greek translation made by Jewish scholars around 200 BC.

These words all translate the Biblical Hebrew word rāqīaʿ (רָקִ֫יעַ), used for example in Genesis 1.6, where it is contrasted with shamayim (שָׁמַיִם), translated as "heaven(s)" in Genesis 1.1. Rāqīaʿ derives from the root rqʿ (רָקַע), meaning "to beat or spread out thinly".[5][6] The Hebrew lexicographers Brown, Driver and Briggs gloss the noun with "extended surface, (solid) expanse (as if beaten out)" and distinguish two main uses: 1. "(flat) expanse (as if of ice), as base, support", and 2. "the vault of heaven, or 'firmament,' regarded by Hebrews as solid and supporting 'waters' above it."[7] A related noun, riqquaʿ (רִקּוּעַ), found in Numbers 16.38 (Hebrew numbering 17.3), refers to the process of hammering metal into sheets.[7] Gerhard von Rad explains:

Rāqīaʿ means that which is firmly hammered, stamped (a word of the same root in Phoenecian means "tin dish"!). The meaning of the verb rqʿ concerns the hammering of the vault of heaven into firmness (Isa. 42.5; Ps.136.6). The Vulgate translates rāqīaʿ with firmamentum, and that remains the best rendering.

— Gerhard von Rad [8]

History edit

Ancient near eastern cosmology edit

Near eastern cosmology is primarily known from cuneiform literature (such as the Enūma Eliš)[9] and the Bible[10]: in particular, the Genesis creation narrative as well as some passing references in the Psalms and the Book of Isaiah. Between these two main sources, there is a fundamental agreement in the cosmological models pronounced: this included a flat and likely disk-shaped world with a solid firmament. The two primary structural representations of the firmament was that it was flat and hovering over the Earth, or that it was a dome and entirely enclosed the Earth's surface. Beyond the firmament is the upper waters, above which further still is the divine abode.[11] The gap between heaven and Earth was bridged by ziggurats and these supported stairways that allowed gods to descend into the Earth from the heavenly realm. A Babylonian clay tablet from the 6th century BC illustrates a world map.[12]

Greek cosmology edit

Prior to the systematic study of the cosmos by the Ionian School in the city of Miletus in the 6th century BC, the early Greek conception of cosmology was closely related to that of near eastern cosmology and envisioned a flat Earth with a solid firmament above the Earth supported by pillars. However, the work of Anaximander, Anaximenes, and Thales, followed by classical Greek theoreticians like Aristotle and Ptolemy ushered in the notions of a spherical Earth and an Earth floating in the center of the cosmos as opposed to resting on a body of water. This picture was geocentric and represented the cosmos as a whole as spherical.[13]

Patristic cosmology edit

One problem for Christian interpreters was in understanding the distinction between the heaven created on the first day and the firmament created in the second day. For Origen, the resolution was in by supposing two heavens and two Earths: a pair created on the first day residing in the invisible and supreme region of creation, and a visible pair (corresponding to the firmament from the second day and the "dry land" from the third) that acted as its corporeal, physical counterpart and as the plain in which humans existed. Appealing to a Platonic division between base and heavenly or spiritual matter, Augustine of Hippo would distinguish between the waters below the firmament and the waters above the firmament. This involved a spiritual interpretation of the upper waters. In this, he was followed by John Scotus Eriugena. Ambrose struggled with understanding how the waters above the firmament could be held up given the spherical nature of the cosmos: the solution was to be sought in God's dominion over the cosmos, in the same way that God held up the Earth in the middle of the cosmos though it has no support.[14] Bede reasoned that the waters might be held in place if they were frozen solid: the siderum caelum (heaven of the celestial bodies) was made firm (firmatum) in the midst of the waters so should be interpreted as having the firmness of crystalline stone (cristallini Iapidis).[15] Gregory of Nyssa suggested that the mountains reached up into the heavens to contain the waters. Basil of Caesarea, in his Hexaemeron depicted a domed firmament with a flat underside that formed a pocket or membrane in which the waters were held. The debate over the maintenance of the waters above the firmament continued into the Middle Ages. These interpretations represent a sizable divergence from near eastern cosmological views of the firmament and its waters above. In addition, medieval debates often honed in on the question of what the upper waters were made of. Various views had already emerged among the Church Fathers, including that it had been made out of air, out of the four elements, or out of a yet-distinct fifth element. Whether the firmament was hard/firm or soft/fluid was also up for debate: the notion of a soft or fluid firmament was held until it was challenged in the 13th century by the introduction oft he Aristotelian-Ptolemaic cosmos, a trend that would only culminate in the 16th century.[16]

Jewish cosmology edit

A distinctive collection of ideas about the cosmos were drawn up and recorded in the rabbinic literature, though the conception is rooted deeply in the tradition of near eastern cosmology recorded in Hebrew, Akkadian, and Sumerian sources, combined with some additional influences in the newer Greek ideas about the structure of the cosmos and the heavens in particular.[17] The rabbis viewed the heavens to be a solid object spread over the Earth, which was described with the biblical Hebrew word for the firmament, raki’a. Two images were used to describe it: either as a dome, or as a tent; the latter inspired from biblical references, though the latter is without an evident precedent.[18] As for its composition, just as in cuneiform literature the rabbinic texts describe that the firmament was made out of a solid form of water, not just the conventional liquid water known on the Earth. A different tradition makes an analogy between the creation of the firmament and the curdling of milk into cheese. Another tradition is that a combination of fire and water makes up the heavens. This is somewhat similar to a view attributed to Anaximander, whereby the firmament is made of a mixture of hot and cold (or fire and moisture).[19] Yet another dispute concerned how thick the firmament was. A view attributed to R. Joshua b. R. Nehemiah was that it was extremely thin, no thicker than two or three fingers. Some rabbis compared it to a leaf. On the other hand, some rabbis viewed it as immensely thick. Estimates that it was as thick as a 50 year journey or a 500 year journey were made. Debates on the thickness of the firmament also impacted debates on the path of the sun in its journey as it passes through the firmament through passageways called the "doors" or "windows" of heaven.[20] The number of heavens or firmaments was often given as more than one: sometimes two, but much more commonly, seven. It is unclear whether the notion of the seven heavens is related to earlier near eastern cosmology or the Greek notion of the surrounding of the Earth by seven concentric spheres: one for the sun, one for the moon, and one for each of the five other (known) planets.[21] A range of additional discussions in rabbinic texts surrounding the firmament included those on the upper waters,[22] the movements of the heavenly bodies and the phenomena of precipitation,[23] and more.[24][25]

The firmament also appears in non-rabbinic Jewish literature, such as in the cosmogonic views represented in the apocrypha. A prominent example is in the Book of Enoch composed around 300 BC. In this text, the sun rises from one of six gates from the east. It crosses the sky and sets into a window through the firmament in the west. The sun then travels behind the firmament back to the other end of the Earth, from whence it could rise again.[26] In the Testament of Solomon, the heavens are conceived in a tripartite structure and demons are portrayed as being capable of flying up to and past the firmament in order to eavesdrop on the decisions of God.[27] Another example of Jewish literature describing the firmament can be found in Samaritan poetry.[28]

Islamic cosmology edit

The Quran describes a concrete firmament above the Earth, built by God and lifted up[29][30]: the firmament is maintained not by any pillars but by God directly maintaining it, in a description resembling that of the Syriac theologian Jacob of Serugh in his Hexaemeron.[31] Another commonality between the two is in describing the firmament as being decorated by stars.[32] The heavens are analogized to a roof, structure, and edifice without crack or fissure. It is extremely broad and stretched, but it is also constantly broadening.[30] Though there has been some dispute over the exact shape of the Quranic firmament (primarily over whether it is flat or domed), the most recent study by Tabatabaʾi and Mirsadri favors a flat firmament.[33] In addition, there are seven heavens or firmaments[34][35] and they were made from smoke during the creation week, resembling the view of Basil of Caesarea.[36]

Modern cosmology edit

The model established by Aristotle became the dominant model in the Classical and Medieval world-view, and even when Copernicus placed the Sun at the center of the system he included an outer sphere that held the stars (and by having the earth rotate daily on its axis it allowed the firmament to be completely stationary). Tycho Brahe's studies of the nova of 1572 and the Comet of 1577 were the first major challenges to the idea that orbs existed as solid, incorruptible, material objects,[37] and in 1584 Giordano Bruno proposed a cosmology without a firmament: an infinite universe in which the stars are actually suns with their own planetary systems.[38] After Galileo began using a telescope to examine the sky it became harder to argue that the heavens were perfect, as Aristotelian philosophy required, and by 1630 the concept of solid orbs was no longer dominant.[37]

Models of the Firmament edit

Perhaps beginning with Origen, the different identifiers use d for heavens in the Book of Genesis, caelum and firmamentum, sparked some commentary on the significance of the order of creation (caelum identified as the heaven of the first day, and firmamentum as the heaven of the second day).[39] Some of these theories identified caelum as the higher, immaterial and spiritual heaven, whereas firmamentum was of corporeal existence.[40]: 237

Christian theologians of note writing between the 5th and mid-12th century were generally in agreement that the waters, sometimes called the "crystalline orb", were located above the firmament and beneath the fiery heaven that was also called empyrean (from Greek ἔμπυρος). One medieval writer who rejected such notions was Pietro d'Abano who argued that theologians "assuming a crystalline, or aqueous sphere, and an empyrean, or firey sphere" were relying on revelation more than Scripture.[41]

About this Ambrose wrote: "Wise men of the world say that water cannot be over the heavens"; the firmament is called such, according to Ambrose, because it held back the waters above it.[42]

See also edit

- Abzu – Primeval sea in Mesopotamian mythology

- Cosmic ocean – Mythological motif

- Flood geology – Pseudoscientific attempt to reconcile geology with the Genesis flood narrative

- Heaven in Judaism – Dwelling place of God and other heavenly beings

- Nu – Ancient Egyptian personification of the primordial watery abyss

- Primum Mobile – Outermost moving sphere in the geocentric model of the universe

- Sky deity – Deity associated with the sky

- Wuji – The primordial in Chinese philosophy

Citations edit

- ^ Rochberg 2010, p. 344.

- ^ Pennington 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Ringgren 1990, p. 92.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary – Firmament". Archived from the original on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ^ Brown, Driver & Briggs 1906, p. 955.

- ^ "Lexicon Results Strong's H7549 – raqiya'". Blue Letter Bible. Blue Letter Bible. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ^ a b Brown, Driver & Briggs 1906, p. 956.

- ^ von Rad 1961, p. 53.

- ^ Horowitz 1998.

- ^ Stadelmann 1970.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 19–20.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 70–71.

- ^ Rochberg 2010, p. 349–350.

- ^ Randles, W. G. L. (1999). The Unmaking of the Medieval Christian Cosmos, 1500–1760. Routledge.

- ^ Rochberg 2010, p. 350–353.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 72.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 72–75.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 75–77.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 77–80.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 80–81.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 81–88.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 88–96.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 150–151.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 149.

- ^ Brannon 2011, p. 196.

- ^ Lieber 2022, p. 137–138.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 180–185.

- ^ a b Tabatabaʾi & Mirsadri 2016, p. 209.

- ^ Decharneux 2019.

- ^ Sinai 2023, p. 413–414.

- ^ Tabatabaʾi & Mirsadri 2016, p. 218–233.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 185–193.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 184.

- ^ Tabatabaʾi & Mirsadri 2016, p. 128–129.

- ^ a b Grant 1996, p. 349.

- ^ Giordano Bruno, De l'infinito universo e mondi (On the Infinite Universe and Worlds), 1584.

- ^ Et vocavit Deus firmamentum caelum.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca (2008). "A Short History of the Waters of the Firmament". In Ross, Micah (ed.). From the Banks of the Euphrates: Studies in Honor of Alice Louise Slotsky. Eisenbrauns. pp. 227–244. ISBN 978-1-57506-144-3.

- ^ Grant 1996, p. 321.

- ^ Boccaletti Dino, The Waters Above the Firmament, p.36 2020

Works cited edit

- Brannon, M. Jeff (2011). The Heavenlies in Ephesians: A Lexical, Exegetical, and Conceptual Analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Brown, Francis; Driver, S.R.; Briggs, Charles A. (1906). A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Decharneux, Julien (2019). "Maintenir le ciel en l'air " sans colonnes visibles " et quelques autres motifs de la creatio continua selon le Coran en dialogue avec les homélies de Jacques de Saroug". Oriens Christianus. 102: 237–267.

- Decharneux, Julien (2023). Creation and Contemplation The Cosmology of the Qur’ān and Its Late Antique Background. De Gruyter.

- Grant, Edward (1996). Planets, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56509-7.

- Hannam, James (2023). The Globe: How the Earth Became Round. Reaktion Books.

- Horowitz, Wayne (1998). Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography. Eisenbrauns.

- Lieber, Laura Suzanne (2022). Classical Samaritan Poetry. Eisenbrauns.

- Pennington, Jonathan T. (2007). Heaven and earth in the Gospel of Matthew. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16205-1.

- Ringgren, Helmer (1990). "Yam". In Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer (eds.). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2330-4.

- Rochberg, Francesca (2010). In the Path of the Moon: Babylonian Celestial Divination and Its Legacy. Brill.

- Simon-Shoshan, Moshe (2008). ""The Heavens Proclaim the Glory of God..." A Study in Rabbinic Cosmology" (PDF). Bekhol Derakhekha Daehu–Journal of Torah and Scholarship. 20: 67–96.

- Sinai, Nicolai (2023). Key Terms of the Qur'an: A Critical Dictionary. Princeton University Press.

- Stadelmann, Luis I.J. (1970). The Hebrew Conception of the World. Biblical Institute Press.

- Tabatabaʾi, Mohammad Ali; Mirsadri, Saida (2016). "The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself". Arabica. 63: 201–234.

- von Rad, Gerhard (1961). Genesis: A Commentary. London: SCM Press.

Further reading edit

- Bandstra, Barry L. (1999). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 0-495-39105-0.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-Creation, Re-Creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11. T&T Clarke International. ISBN 978-0-567-57455-8.

- Broadie, Sarah (1999). "Rational Theology". In Long, A.A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44667-9.

- Clifford, Richard J (2017). "Creatio ex Nihilo in the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible". In Anderson, Gary A.; Bockmuehl, Markus (eds.). Creation ex nihilo: Origins, Development, Contemporary Challenges. University of Notre Dame. ISBN 978-0-268-10256-2.

- Couprie, Dirk L. (2011). Heaven and Earth in Ancient Greek Cosmology: From Thales to Heraclides Ponticus. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-8116-5.

- Grunbaum, Adolf (2013). "Science and the Improbability of God". In Meister, Chad V.; Copan, Paul (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-78294-4.

- James, E.O. (1969). Creation and Cosmology: A Historical and Comparative Inquiry. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-37807-0.

- López-Ruiz, Carolina (2010). When the Gods Were Born: Greek Cosmogonies and the Near East. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04946-8.

- May, Gerhard (2004). Creatio ex nihilo. T&T Clarke International. ISBN 978-0-567-45622-9.

- Nebe, Gottfried (2002). "Creation in Paul's Theology". In Hoffman, Yair; Reventlow, Henning Graf (eds.). Creation in Jewish and Christian Tradition. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84127-162-0.

- Pruss, Alexander (2007). "Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit". In Campbell, Joseph Keim; O'Rourke, Michael; Silverstein, Harry (eds.). Causation and Explanation. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03363-3.

- Rubio, Gonzalez (2013). "Time Before Time: Primeval Narratives in Early Mesopotamian Literature". In Feliu, L.; Llop, J. (eds.). Time and History in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 56th Recontre Assyriologique Internationale at Barcelona, 26–30 July 2010. Eisenbrauns. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- von Rad, Gerhard (1961). Genesis: A Commentary. London: SCM Press.[ISBN missing]

- Waltke, Bruce K. (2011). An Old Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-86332-8.

- Walton, John H. (2006). Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2750-0.

- Walton, John H. (2015). The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-9771-1.

- Wasilewska, Ewa (2000). Creation Stories of the Middle East. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85302-681-2.

- Wolfson, Harry Austryn (1976). The Philosophy of the Kalam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-66580-4.

- Wolters, Albert M. (1994). "Creatio ex nihilo in Philo". In Helleman, Wendy (ed.). Hellenization Revisited: Shaping a Christian Response Within the Greco-Roman World. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-9544-9.

External links edit

- The Vault of Heaven.