Summary

Harold Godwinson (c. 1022 – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066[1] until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the Conqueror during the Norman Conquest of England. His death marked the end of Anglo-Saxon rule over England.

| Harold Godwinson | |

|---|---|

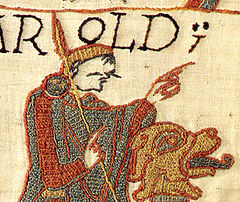

Harold Godwinson, from the Bayeux Tapestry | |

| King of the English | |

| Reign | 5 January – 14 October 1066 |

| Coronation | 6 January 1066 |

| Predecessor | Edward the Confessor |

| Successor |

|

| Born | c. 1022 Wessex, England |

| Died | 14 October 1066 (aged about 44) near Senlac Hill, Sussex, England |

| Burial | Waltham Abbey, Essex, or Bosham, Sussex (disputed) |

| Spouses | |

| Issue | |

| House | Godwin |

| Father | Godwin, Earl of Wessex |

| Mother | Gytha Thorkelsdóttir |

Harold Godwinson was a member of a prominent Anglo-Saxon family with ties to Cnut the Great. He became a powerful earl after the death of his father, Godwin, Earl of Wessex. After his brother-in-law, King Edward the Confessor, died without an heir on 5 January 1066, the Witenagemot convened and chose Harold to succeed him; he was probably the first English monarch to be crowned in Westminster Abbey. In late September, he successfully repelled an invasion by rival claimant Harald Hardrada of Norway in York before marching his army back south to meet William the Conqueror at Hastings two weeks later.

Family background edit

Harold was a son of Godwin (c. 1001–1053), the powerful earl of Wessex, and of Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, whose brother Ulf the Earl was married to Estrid Svendsdatter (c. 1015/1016), the daughter of King Sweyn Forkbeard[2] (died 1014) and sister of King Cnut the Great of England and Denmark. Ulf and Estrid's son would become King Sweyn II of Denmark[3] in 1047. Godwin was the son of Wulfnoth, probably a thegn and a native of Sussex. Godwin began his political career by supporting King Edmund Ironside (reigned April to November 1016), but switched to supporting King Cnut by 1018, when Cnut named him Earl of Wessex.[4]

Godwin remained an earl throughout the remainder of Cnut's reign, one of only two earls to survive to the end of that reign.[5] On Cnut's death in 1035, Godwin originally supported Harthacnut instead of Cnut's initial successor Harold Harefoot, but managed to switch sides in 1037—although not without becoming involved in the 1036 murder of Alfred Aetheling, half-brother of Harthacnut and younger brother of the later King Edward the Confessor.[6]

When Harold Harefoot died in 1040, Harthacnut ascended the English throne and Godwin's power was imperiled by his earlier involvement in Alfred's murder, but an oath and large gift secured the new king's favour for Godwin.[7] Harthacnut's death in 1042 probably involved Godwin in a role as kingmaker, helping to secure the English throne for Edward the Confessor. In 1045 Godwin reached the height of his power when the new king married Godwin's daughter Edith.[8]

Godwin and Gytha had several children—six sons: Sweyn, Harold, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth (in that order); and three daughters: Edith of Wessex (originally named Gytha but renamed Ealdgyth (or Edith) when she married King Edward the Confessor), Gunhild and Ælfgifu. The birthdates of the children are unknown.[9] Harold was aged about 25 in 1045, which makes his birth year around 1020.[10]

Powerful nobleman edit

Edith married Edward on 23 January 1045 and, around that time, Harold became Earl of East Anglia. Harold is called "earl" when he appears as a witness in a will that may date to 1044; but, by 1045, Harold regularly appears as an earl in documents. One reason for his appointment to East Anglia may have been a need to defend against the threat from King Magnus the Good of Norway. It is possible that Harold led some of the ships from his earldom that were sent to Sandwich in 1045 against Magnus.[11] Sweyn, Harold's elder brother, had been named an earl in 1043.[12] It was also around the time that Harold was named an earl that he began a relationship with Edith the Fair, who appears to have been the heiress to lands in Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and Essex, lands in Harold's new earldom.[13] The relationship was a form of marriage that was not blessed or sanctioned by the Church, known as More danico, or "in the Danish manner", and was accepted by most laypeople in England at the time. Any children of such a union were considered legitimate. Harold probably entered the relationship in part to secure support in his new earldom.[14]

Harold's elder brother Sweyn was exiled in 1047 after abducting the abbess of Leominster. Sweyn's lands were divided between Harold and a cousin, Beorn.[15] In 1049, Harold was in command of a ship or ships that were sent with a fleet to aid Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor against Baldwin V, Count of Flanders, who was in revolt against Henry. During this campaign, Sweyn returned to England and attempted to secure a pardon from the king, but Harold and Beorn refused to return any of their lands, and Sweyn, after leaving the royal court, took Beorn hostage and later killed him.[16]

In 1051, Edward appointed an enemy of the Godwins as Archbishop of Canterbury and soon afterwards drove them into exile, but they raised an army which forced the king to restore them to their positions a year later. Earl Godwin died in 1053, and Harold succeeded him as Earl of Wessex, which made him the most powerful lay figure in England after the king.[17]

In 1055, Harold drove back the Welsh, who had burned Hereford.[18] Harold also became Earl of Hereford in 1058, and replaced his late father as the focus of opposition to growing Norman influence in England under the restored monarchy (1042–66) of Edward the Confessor, who had spent more than 25 years in exile in Normandy. He led a series of successful campaigns (1062–63) against Gruffydd ap Llywelyn of Gwynedd, king of Wales. This conflict ended with Gruffydd's defeat and death in 1063.[19]

Harold in northern France edit

In 1064, Harold was apparently shipwrecked at Ponthieu. There is much speculation about this voyage. The earliest post-conquest Norman chroniclers state that King Edward had previously sent Robert of Jumièges, the archbishop of Canterbury, to appoint as his heir Edward's maternal kinsman, Duke William II of Normandy, and that at this later date Harold was sent to swear fealty.[20] Scholars disagree as to the reliability of this story. William, at least, seems to have believed he had been offered the succession, but some acts of Edward are inconsistent with his having made such a promise, such as his efforts to return his nephew Edward the Exile, son of King Edmund Ironside, from Hungary in 1057.[a]

Later Norman chroniclers suggest alternative explanations for Harold's journey: that he was seeking the release of members of his family who had been held hostage since Godwin's exile in 1051, or even that he had simply been travelling along the English coast on a hunting and fishing expedition and had been driven across the English Channel by an unexpected storm. There is general agreement that he left from Bosham, and was blown off course, landing at Ponthieu. He was captured by Count Guy I of Ponthieu, and was then taken as a hostage to the count's castle at Beaurain,[b] 24.5 km (15.2 mi) up the River Canche from its mouth at what is now Le Touquet. William arrived soon afterward and ordered Guy to turn Harold over to him.[21]

Harold then apparently accompanied William to battle against William's enemy, Conan II, Duke of Brittany. While crossing into Brittany past the fortified abbey of Mont Saint-Michel, Harold is recorded as rescuing two of William's soldiers from quicksand. They pursued Conan from Dol-de-Bretagne to Rennes, and finally to Dinan, where he surrendered the fortress's keys at the point of a lance. William presented Harold with weapons and arms, knighting him. The Bayeux Tapestry, and other Norman sources, then state that Harold swore an oath on sacred relics to William to support his claim to the English throne. After Edward's death, the Normans were quick to claim that in accepting the crown of England, Harold had broken this alleged oath.[22]

The chronicler Orderic Vitalis wrote of Harold that he "was distinguished by his great size and strength of body, his polished manners, his firmness of mind and command of words, by a ready wit and a variety of excellent qualities. But what availed so many valuable gifts, when good faith, the foundation of all virtues, was wanting?"[23]

Due to a doubling of taxation by Tostig in 1065 that threatened to plunge England into civil war, Harold supported Northumbrian rebels against his brother, and replaced him with Morcar. This led to Harold's marriage alliance with the northern earls but fatally split his own family, driving Tostig into alliance with King Harald Hardrada ("Hard Ruler") of Norway.[1]

Reign edit

At the end of 1065, King Edward the Confessor fell into a coma without clarifying his preference for the succession. He died on 5 January 1066, according to the Vita Ædwardi Regis, but not before briefly regaining consciousness and commending his widow and the kingdom to Harold's "protection". The intent of this charge remains ambiguous, as is the Bayeux Tapestry, which simply depicts Edward pointing at a man thought to represent Harold.[c] When the Witan convened the next day they selected Harold to succeed,[d] and his coronation followed on 6 January, most likely held in Westminster Abbey, though limited but persuasive evidence from the time survives to confirm this, in the form of its depiction in the Bayeux Tapestry (shown above left).[25] Although later Norman sources point to the suddenness of this coronation, the reason may have been that all the nobles of the land were present at Westminster for the feast of Epiphany, and not because of any usurpation of the throne on Harold's part.

In early January 1066, upon hearing of Harold's coronation, William began plans to invade England, building 700 warships and transports at Dives-sur-Mer on the Normandy coast. Initially, William struggled to gain support for his cause, however, after claiming that Harold had broken an oath sworn on sacred relics, Pope Alexander II formally declared William the rightful heir of the throne of England and nobles flocked to his cause.[citation needed] In preparation of the invasion, Harold assembled his troops on the Isle of Wight, but the invasion fleet remained in port for almost seven months, perhaps due to unfavourable winds. On 8 September, with provisions running out, Harold disbanded his army and returned to London. On the same day, the invasion force of Harald Hardrada, [e] accompanied by Tostig, landed at the mouth of the Tyne.

The invading forces of Hardrada and Tostig defeated the English earls Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria at the Battle of Fulford near York on 20 September 1066. Harold led his army north on a forced march from London, reached Yorkshire in four days, and caught Hardrada by surprise. On 25 September, in the Battle of Stamford Bridge, Harold defeated Hardrada and Tostig, who were both killed.

According to Snorri Sturluson, in a story described by Edward Freeman as "plainly mythical",[26] before the battle a single man rode up alone to Harald Hardrada and Tostig. He gave no name, but spoke to Tostig, offering the return of his earldom if he would turn against Hardrada. Tostig asked what his brother Harold would be willing to give Hardrada for his trouble. The rider replied "Seven feet of English ground, as he is taller than other men." Then he rode back to the Saxon host. Hardrada was impressed by the rider's boldness, and asked Tostig who he was. Tostig replied that the rider was Harold Godwinson himself.[27]

Battle of Hastings edit

HIC CECIDERUNT LEVVINE ET GYRÐ FRATRES HAROLDI REGIS

(Here have fallen dead Leofwine and Gyrth, brothers of King Harold)

On 12 September 1066 William's fleet sailed from Normandy. Several ships sank in storms, which forced the fleet to take shelter at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme and to wait for the wind to change. On 27 September the Norman fleet set sail for England, arriving the following day at Pevensey on the coast of East Sussex. Harold's army marched 240 miles (390 kilometres) to intercept William, who had landed perhaps 7,000 men in Sussex, southern England. Harold established his army in hastily built earthworks near Hastings. The two armies clashed at the Battle of Hastings, at Senlac Hill (near the present town of Battle) close by Hastings on 14 October, where after nine hours of hard fighting, Harold was killed and his forces defeated. His brothers Gyrth and Leofwine were also killed in the battle.[28][29] [30]

Death edit

The widely held belief that Harold died by an arrow to the eye is a subject of much scholarly debate. A Norman account of the battle, Carmen de Hastingae Proelio ("Song of the Battle of Hastings"), said to have been written shortly after the battle by Guy, Bishop of Amiens, says that Harold was lanced and his body dismembered by four knights, probably including Duke William. Twelfth-century Anglo-Norman histories, such as William of Malmesbury's Gesta Regum Anglorum and Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum recount that Harold died by an arrow wound to his head. An earlier source, Amatus of Montecassino's L'Ystoire de li Normant ("History of the Normans"), written only twenty years after the battle of Hastings, contains a report of Harold being shot in the eye with an arrow, but this may be an early fourteenth-century addition.[31] Later accounts reflect one or both of these two versions.

In the panel of the Bayeux Tapestry with the inscription "Hic Harold Rex Interfectus Est" ("Here King Harold is killed") a figure standing below the inscription is currently depicted gripping an arrow that has struck his eye. This, however, may have been a late 18th or early 19th-century modification to the Tapestry.[32] Some historians have questioned whether this man is intended to be Harold or if the panel shows two instances of Harold in sequence of his death[33] the figure standing to the left of the central figure commonly thought to be Harold, and then lying to the right almost supine being mutilated beneath a horse's hooves. Etchings made of the Tapestry in the 1730s show the standing figure with differing objects. Benoît's 1729 sketch shows only a dotted line indicating stitch marks which is longer than the currently shown arrow and without any indication of fletching, whereas all other arrows in the Tapestry are fletched. Bernard de Montfaucon's 1730 engraving has a solid line resembling a spear being held overhand matching the manner of the standing figure currently depicted with an arrow to the eye; while stitch marks for where such a spear may have been removed can be seen in the Tapestry.[33] In 1816 Charles Stothard was commissioned by the Society of Antiquaries of London to make a copy of the Bayeux Tapestry. He included in his reproduction previously damaged or missing parts of the work with his own hypothesised depictions. This is when the arrow first appears.[f][33] It has been proposed that the supine figure once had an arrow added by over-enthusiastic nineteenth-century restorers that was later unstitched.[35] Many believe the figure with an arrow in his eye to be Harold as the name "Harold" is above him. This has been disputed by examining other examples from the Tapestry where the visual centre of a scene, not the location of the inscription, identifies named figures.[36] A further suggestion is that both accounts are accurate, and that Harold suffered first the eye wound, then the mutilation, and the Tapestry is depicting both in sequence.[37]

Burial and legacy edit

The account of the contemporary chronicler William of Poitiers states that the body of Harold was given to William Malet for burial:

The two brothers of the King were found near him and Harold himself, stripped of all badges of honour, could not be identified by his face but only by certain marks on his body. His corpse was brought into the Duke's camp, and William gave it for burial to William, surnamed Malet, and not to Harold's mother, who offered for the body of her beloved son its weight in gold. For the Duke thought it unseemly to receive money for such merchandise, and equally he considered it wrong that Harold should be buried as his mother wished, since so many men lay unburied because of his avarice. They said in jest that he who had guarded the coast with such insensate zeal should be buried by the seashore.

— William of Poitiers, Gesta Guillelmi II Ducis Normannorum, William of Poitiers 1953, p. 229

Another source states that Harold's widow, Edith the Fair,[g] was called to identify the body, which she did by some private mark known only to her. Harold's strong association with Bosham, his birthplace, and the discovery in 1954 of an Anglo-Saxon coffin in the church there, has led some to suggest it as the place of King Harold's burial. A request to exhume a grave in Bosham Church was refused by the Diocese of Chichester in December 2003, the Chancellor having ruled that the chances of establishing the identity of the body as Harold's were too slim to justify disturbing a burial place.[38][39] The exhumation in 1954 had revealed the remains of a man in a coffin. "[It] was made of Horsham stone, magnificently finished, and contained the thigh and pelvic bones of a powerfully built man of about 5ft 6in[h] in height, aged over 60 years[i] and with traces of arthritis."[38] It was suggested that the contents of the coffin had been opened at a much earlier date and vandalised, as the skull was missing and the remaining bones damaged in a way that was inconsistent with decomposition post mortem.[38] The description of the remains is not unlike the fate of the king recorded in the Carmen de Hastingae Proeliormen. The poem also claims Harold was buried by the sea, which is consistent with William of Poitiers' account and with the identification of the grave at Bosham Church that is only yards from Chichester Harbour and in sight of the English Channel.[39]

There were legends of Harold's body being given a proper funeral years later in Waltham Abbey Church in Essex, which he had refounded in 1060. Legends also grew up that Harold had not died at Hastings but instead fled England or that he later ended his life as a hermit at Chester or Canterbury.[41]

Harold's son Ulf, along with Morcar and two others, were released from prison by King William as he lay dying in 1087. Ulf threw his lot in with Robert Curthose, who knighted him, and then disappeared from history. Two of Harold's other sons, Godwine and Edmund, invaded England in 1068 and 1069 with the aid of Diarmait mac Máel na mBó (High King of Ireland) but were defeated at the Battle of Northam in Devon in 1069.[j] In 1068, Diarmait presented another Irish king with Harold's battle standard.[42]

Some Eastern Orthodox Christians controversially view King Harold as a saint, though he has not been officially glorified (canonised) by the Orthodox Church. Supporters of Harold's sainthood view him as a potential Martyr or Passion Bearer.[43] Among English-speaking Orthodox Christians there has been some interest in creating iconography and localised veneration.[44]

Marriages and children edit

Harold was married[k] to Edith the Fair[g] for approximately twenty years and had at least five children with her.[45]

According to Orderic Vitalis, Harold was at some time betrothed to Adeliza, a daughter of William the Conqueror; if so, the betrothal never led to marriage.[47]

In about January 1066, Harold married Ealdgyth, daughter of Earl Ælfgar, and widow of the Welsh prince Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. After her husband's death, at the Battle of Hastings, the pregnant Ealdgyth had been collected, from London, by her brothers, the Northern earls, Edwin of Mercia and Morcar of Northumbria, and taken to Chester for safety. It is not known what happened to her thereafter.[48]

Some historians have suggested that Harold and Ealdgyth's union was childless,[48] others ascribe two children to Ealdgyth, named Harold and Wulf/Ulf.[49] Because of the chronology it is likely that the boys would have been twins and born after the demise of their father. Another possibility is that Ulf was the son of Edith the Fair.[49]

There is a tradition that Edith the Fair took the broken body of her husband Harold Godwinson to the Church at Waltham Holy Cross to be buried. What happened to her after 1066, is not known. Also, after their defeat at the Battle of Northam the fate of the sons is unclear although some later sources suggest they took refuge at the Danish court with their grandmother, aunt and sister.[17][50][51]

References edit

Notes edit

- ^ Edward may not have been blameless in this situation, as at least one other man, Sweyn II of Denmark, also thought Edward had promised him the succession.[20]

- ^ Bayeux Tapestry, in which the place is called in Latin Belrem

- ^ Frank Barlow points out that the author of the Vita, who appears to have looked favourably on Harold, was writing after the Conquest and may have been intentionally vague.[24]

- ^ This was in preference to Edward's great-nephew, Edgar the Ætheling, who had yet to reach maturity.

- ^ Who also claimed the English crown through a succession pact concluded between Harthacnut, king of England and Denmark, and Magnus I of Norway, whereby the kingdoms of the first to die were to pass to the survivor. Magnus had thus gained a claim to Denmark on Harthacnut's death but had not pursued this other crown. Hardrada, uncle and heir of Magnus, now claimed England on this basis.

- ^ Stothard's is the first record of the Bayeux Tapestry after it was damaged during the French Revolution and before repairs were carried out in the 19th century.[34]

- ^ a b also known as Edyth Swannesha (Edith Swanneck)

- ^ 5.5 feet (1.7 m)

- ^ Harold was thought to have been in his 40s at his death[40]

- ^ At midsummer in 1069, Brian of Brittany and Alan the Black led a force that defeated a raid by Godwine and Edmund, sons of Harold Godwinson, who had sailed from Ireland with a fleet of 64 ships to the mouth of the River Taw in Devon. They had escaped to Leinster after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 where they were hosted by Diarmait. In 1068 and 1069 Diarmait lent them the fleet of Dublin for their attempted invasions of England.

- ^ The pagan English had been polygynous. When the Anglo-Saxons were evangelized although by church law concubinage would not have been legally ratified, it was largely acknowledged by custom. Edith's marriage was described as more danico (in the Danish fashion) which means unblessed by the church.[45][46]

Citations edit

- ^ a b DeVries 1999, p. 230.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Barlow 1988, p. 451.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Mason, Emma (2004). House of Godwine: The History of Dynasty. London: Hambledon & London. p. 35. ISBN 1-8528-5389-1.

- ^ Rex, Peter (2005). Harold II: The Doomed Saxon King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7394-7185-2.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Barlow 1970, p. 74.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Fleming 2010.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 11.

- ^ "Harold II". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ a b Howarth 1983, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Howarth 1983, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Freeman 1869, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Ordericus Vitalis 1853, pp. 459–460.

- ^ Barlow 1970, p. 251.

- ^ "Westminster Abbey Official site – Coronations"

- ^ Freeman 1869, p. 365.

- ^ Sturluson, Snorri (1966). King Harald's Saga. Baltimore, Maryland: Penguin Books. p. 149.

- ^ Brown 1980, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Grainge & Grainge 1999, pp. 130–142.

- ^ Freeman 1999, pp. 150–164.

- ^ Foys 2010, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Foys 2016.

- ^ a b c Livingston 2022.

- ^ Society of Antiquaries of London (2020). "Bayeux Tapestry". London: College of Antiquaries. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Bernstein 1986, pp. 148–152.

- ^ Foys 2010, pp. 171–175.

- ^ Brooks, N. P.; Walker, H. E. (1997). "The Authority and Interpretation of the Bayeux Tapestry". In Gameson, Richard (ed.). The Study of the Bayeux Tapestry. Boydell and Brewer. pp. 63–92. ISBN 0-8511-5664-9.

- ^ a b c Hill 2003.

- ^ a b Bosham Online 2003.

- ^ Fryde et al. 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Bartlett & Jeffery 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Moss 2011.

- ^ Philips 1995, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Barlow 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Ross 1985, pp. 3–34.

- ^ Round 1885.

- ^ a b Maund 2004.

- ^ a b Barlow 2013, p. 128.

- ^ Barlow 2013, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Arnold 2014, pp. 34–56.

Sources edit

- Arnold, Nick (2014). "The Defeat of the sons of Harold in 1069". Report and Transactions. 146. Barnstable: The Devonshire Association: 33–56. ISSN 0309-7994. OCLC 5840886678.

- Barlow, Frank (1970). Edward the Confessor. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5200-1671-2.

- Barlow, Frank (1988). The Feudal Kingdom of England 1042–1216 (Fourth ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0-5824-9504-0.

- Barlow, Frank (2013). The Godwins: The Rise and Fall of a Noble Dynasty. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-5827-8440-6.

- Bartlett, Thomas; Jeffery, Keith (1997). A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-5216-2989-8.

- Bernstein, David (1986). The Mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry. Univ of Chicago Pr. ISBN 0-2260-4400-9.

- Bosham Online (25 November 2003). "The Debate concerning the remains found in Bosham Church". Bosham Community Website. The Bosham Online Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- Brown, R. Allen, ed. (1980). Anglo-Norman Studies III: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1980. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-8511-5141-8.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press – via Wikisource.

- DeVries, Kelly (1999). The Norwegian Invasion of England in 1066. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 978-1-8438-3027-6.

- Fleming, Robin (23 September 2010). "Harold II [Harold Godwineson] (1022/3?–1066)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12360. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Foys, Martin (2010). "Pulling the Arrow Out: The Legend of Harold's Death and the Bayeux Tapestry". In Foys; Overbey, Karen Eileen; Terkla, Dan (eds.). Bayeux Tapestry: New Interpretations. Boydell and Brewer. pp. 158–75. ISBN 978-1-8438-3470-0.

- Foys, Martin (2016). "Shot through the eye and who's to blame?". History Today. 66 (10). London: History Today Ltd.

- Freeman, Edward Augustus (1869). The History of the Norman Conquest of England: The Reign of Harold and the Interregnum. New York: Macmillan.

- Freeman, Edward Augustus (1999). "Interpretations: The Battle". In Morillo, Stephen (ed.). The Battle of Hastings. Warfare in History. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0-8511-5619-3.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I., eds. (2003). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd, reprinted ed.). Cambridge: University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-8619-3106-8.

- Grainge, Christine; Grainge, Gerald (1999). "Intepretations:The Pevensey Expedition: Brilliantly Executed plan or near disaster". In Morillo, Stephen (ed.). The Battle of Hastings. Warfare in History. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 130–142. ISBN 0-8511-5619-3.

- Hill, Mark (2003). "Consistory Court Judgment CH 79/03" (PDF). Chichester: Consistory Court of the Diocese of Chichester. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- Howarth, David (1983). 1066: The Year of the Conquest. Penguin Books.

- Livingston, Michael (2022). "The Arrow in King Harold's Eye: The Legend That Just Won't Die". Medievalists.net. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- Maund, K.L. (23 September 2004). "Ealdgyth [Aldgyth]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/307. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Moss, Vladimir (2011). The Fall of Orthodox England. Lulu Publishing.

- Philips, Andrew (1995). Orthodox Christianity and the English Tradition. English Orthodox Trust.

- Ross, Margaret Clunies (1985). "Concubinage in Anglo-Saxon England". Past & Present. 108 (108). Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society: 3–34. doi:10.1093/past/108.1.3. JSTOR 650572.

- Round, J. H. (1885). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Ordericus Vitalis (1853). The Ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy. Vol. 1 Bk 3. Translated by Forester, Thomas. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Walker, Ian (2000). Harold the Last Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucestershire: Wrens Park. ISBN 0-9057-7846-4.

- William of Poitiers (1953). Douglas, David; Greenaway, George W. (eds.). Gesta Guillelmi II Ducis Normannorum. English Historical Documents 1042-1189. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Oxford: Routledge.

Further reading edit

- Freeman, Edward Augustus (1871). The History of the Norman Conquest of England: Its Causes and Its Results. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- van Kempen, Ad F. J. (November 2016). "'A mission he bore – to Duke William he came': Harold Godwineson's Commentum and his covert ambitions". Historical Research. 89 (246): 591–612. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.12147.

External links edit

- Harold II at the official website of the British monarchy

- Harold 3 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- BBC Historic Figures: Harold II (Godwineson) (c. 1020–1066)

- Portraits of King Harold II (Harold Godwineson) at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Society of Antiquaries