Summary

The Kingdom of the East Saxons (Old English: Ēastseaxna rīce; Latin: Regnum Orientalium Saxonum), referred to as the Kingdom of Essex /ˈɛsɪks/, was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy.[a] It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Middlesex, much of Hertfordshire and (for a short while) west Kent. The last king of Essex was Sigered of Essex, who in 825 ceded the kingdom to Ecgberht, King of Wessex. From 825 Essex was ruled as part of a south-eastern kingdom of Essex, Kent, Sussex and Surrey. It was not until 860 that Essex was fully integrated into the crown of Wessex.

Kingdom of the East Saxons | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 527–825 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Common languages | Old English | ||||||||

| Religion | Paganism (before 7th century) Christianity (after 7th century) | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 527–587 | Æscwine (first) | ||||||||

• 798–825 | Sigered (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Witenagemot | ||||||||

| Historical era | Heptarchy | ||||||||

• Established | 527 | ||||||||

• Full integration into crown of Wessex | 825 | ||||||||

| Currency | Sceat | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Extent edit

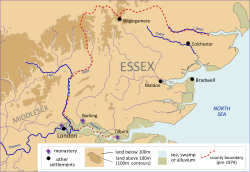

The Kingdom of Essex was bounded to the north by the River Stour and the Kingdom of East Anglia, to the south by the River Thames and Kent, to the east lay the North Sea and to the west Mercia. The territory included the remains of two provincial Roman capitals, Colchester and London.

The kingdom included the Middle Saxon Province,[1] which included the area of the later county of Middlesex, and most if not all of Hertfordshire[2] Although the province is only ever recorded as a part of the East Saxon kingdom, charter evidence shows that it was not part of their core territory. In the core area they granted charters freely, but further west they did so while also making reference to their Mercian overlords. At times, Essex was ruled jointly by co-Kings, and it thought that the Middle Saxon Province is likely to have been the domain of one of these co-kings.[3] The links to Essex between Middlesex and parts of Hertfordshire were long reflected in the Diocese of London, re-established in 604 as the East Saxon see, and its boundaries continued to be based on the Kingdom of Essex until the nineteenth century.

The East Saxons also had intermittent control of Surrey.[4] For a brief period in the 8th century, the Kingdom of Essex controlled west Kent.

The modern English county of Essex maintains the historic northern and the southern borders, but only covers the territory east of the River Lea, the other parts being lost to neighbouring Mercia during the 8th century.[2]

In the Tribal Hidage it is listed as containing 7,000 hides.

History edit

Although the kingdom of Essex was one of the kingdoms of the Heptarchy, its history is not well documented. It produced relatively few Anglo-Saxon charters[5] and no version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; in fact the only mention in the chronicle concerns Bishop Mellitus.[6] As a result, the kingdom is regarded as comparatively obscure.[7] For most of the kingdom's existence, the Essex king was subservient to an overlord – variously the kings of Kent, East Anglia or Mercia.[8]

Origin edit

Saxon occupation of land that was to form the kingdom had begun by the early 5th century at Mucking and other locations. A large proportion of these original settlers came from Old Saxony.[9] According to British legend (see Historia Brittonum) the territory known later as Essex was ceded by the Celtic Britons to the Saxons following the infamous Treason of the Long Knives, which occurred c. 460 during the reign of High King Vortigern. Della Hooke relates the territory ruled by the kings of Essex to the pre-Roman territory of the Trinovantes.[10] Studies suggest a pattern of typically peaceful co-existence, with the structure of the Romano-British landscape being maintained, and with the Saxon settlers believed to have been in the minority.[11]

The kingdom of Essex grew by the absorption of smaller subkingdoms[12] or Saxon tribal groups. There are a number of suggestions for the location of these subkingdoms including:

- The Rodings ("the people of Hrōþa"),[12]

- the Haemele, Hemel Hempstead[13]

- Vange[14] – "marsh district" (possibly stretching to the Mardyke)

- Denge[5]

- Ginges[13]

- Berecingas – Barking, in the south west of the kingdom[15][16]

- Haeferingas in the London Borough of Havering[15]

- Uppingas – Epping[15]

Essex monarchy edit

Essex emerged as a single kingdom during the 6th century. The dates, names and achievements of the Essex kings, like those of most early rulers in the Heptarchy, remain conjectural. The historical identification of the kings of Essex, including the evidence and a reconstructed genealogy are discussed extensively by Yorke.[17] The dynasty claimed descent from Woden via Seaxnēat. A genealogy of the Essex royal house was prepared in Wessex in the 9th century. Unfortunately, the surviving copy is somewhat mutilated.[18] At times during the history of the kingdom several sub-kings within Essex appear to have been able to rule simultaneously.[2] They may have exercised authority over different parts of the kingdom. The first recorded king, according to the East Saxon King List, was Æscwine of Essex, to which a date of 527 is given for the start of his reign, although there are some difficulties with the date of his reign, and Sledd of Essex is listed as the founder of the Essex royal house by other sources.[19] The kings of Essex are notable for their S-nomenclature, nearly all their names begin with the letter S.

The Essex kings issued coins that echoed those issued by Cunobeline simultaneously asserting a link to the first century rulers while emphasising independence from Mercia.[20]

Christianity edit

Christianity is thought to have flourished among the Trinovantes in the 4th century (late Roman period); indications include the remains of a probable church at Colchester,[21] dating from some time after 320 AD, shortly after the Constantine the Great granted freedom of worship to Christians in 313 AD. Other archaeological evidence includes a chi rho symbol etched on a tile at a site in Wickford, and a gold ring inscribed with a chi rho monogram found at Brentwood.[22] It is not clear to what extent, if any, Christianity persisted by the time of the pagan East Saxon kings in the sixth century.

The earliest English record of the kingdom dates to Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, which noted the arrival of Bishop (later Saint) Mellitus in London in 604. Æthelberht (King of Kent and overlord of southern England according to Bede) was in a position to exercise some authority in Essex shortly after 604, when his intervention helped in the conversion of King Saebert of Essex (son of Sledd), his nephew, to Christianity. It was Æthelberht, and not Sæberht, who built and endowed St. Paul's in London, where St. Paul's Cathedral now stands. Bede describes Æthelberht as Sæberht's overlord.[23][24] After the death of Saebert in AD 616, Mellitus was driven out and the kingdom reverted to paganism. This may have been the result of opposition to Kentish influence in Essex affairs rather than being specifically anti-Christian.[25]

The kingdom reconverted to Christianity under Sigeberht II the Good following a mission by St Cedd who established monasteries at Tilaburg (probably East Tilbury, but possibly West Tilbury) and Ithancester (almost certainly Bradwell-on-Sea). A royal tomb at Prittlewell was discovered and excavated in 2003. Finds included gold foil crosses, suggesting the occupant was Christian. If the occupant was a king, it was probably either Saebert or Sigeberht (murdered AD 653). It is, however, also possible that the occupant was not royal, but simply a wealthy and powerful individual whose identity has gone unrecorded.[26]

Essex reverted to Paganism again in 660 with the ascension of the Pagan King Swithelm of Essex. He converted in 662, but died in 664. He was succeeded by his two sons, Sigehere and Sæbbi. A plague the same year caused Sigehere and his people to recant their Christianity and Essex reverted to Paganism a third time. This rebellion was suppressed by Wulfhere of Mercia who established himself as overlord. Bede describes Sigehere and Sæbbi as "rulers […] under Wulfhere, king of the Mercians".[27] Wulfhere sent Jaruman, the bishop of Lichfield, to reconvert the East Saxons.[28]

Wine (in 666)[29] and Erkenwald (in 675)[29] were appointed bishops of London with spiritual authority over the East Saxon Kingdom. A small stone chest bearing the name of Sæbbi of Essex (r. 664–683) was visible in Old St Paul's Cathedral until the Great Fire of London of 1666 when the cathedral and the tombs within it were lost. The inscription on the chest was recorded by Paul Hentzner and translated by Robert Naunton as reading: "Here lies Seba, King of the East Saxons, who was converted to the faith by St. Erkenwald, Bishop of London, A.D. 677."[30]

Although London (and the rest of Middlesex) was lost by the East Saxons in the 8th century, the bishops of London continued to exert spiritual authority over Essex as a kingdom, shire and county until 1845.[31]

Later history and end edit

Despite the comparative obscurity of the kingdom, there were strong connections between Essex and the Kentish kingdom across the river Thames which led to the marriage of King Sledd to Ricula, sister of the king, Aethelbert of Kent. For a brief period in the 8th century the kingdom included west Kent. During this period, Essex kings were issuing their own sceattas (coins), perhaps as an assertion of their own independence.[32] However, by the mid-8th century, much of the kingdom, including London, had fallen to Mercia and the rump of Essex, roughly the modern county, was now subordinate to the same.[33] After the defeat of the Mercian king Beornwulf around AD 825, Sigered, the last king of Essex, ceded the kingdom which then became a possession of the Wessex king Egbert.[34]

The Mercians continued to control parts of Essex and may have supported a pretender to the Essex throne since a Sigeric rex Orientalem Saxonum witnessed a Mercian charter after AD 825.[35][36] During the ninth century, Essex was part of a sub-kingdom that included Sussex, Surrey and Kent.[36] Sometime between 878 and 886, the territory was formally ceded by Wessex to the Danelaw kingdom of East Anglia, under the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum. After the reconquest by Edward the Elder the king's representative in Essex was styled an ealdorman and Essex came to be regarded as a shire.[37]

List of kings edit

The following list of kings may omit whole generations.

| Reign | Incumbent | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 527 to 587 | (perhaps) Æscwine or Erchenwine | First king according to some sources, others saying son Sledd was first |

| 587 to ante 604 | Sledd | Son of Æscwine/Erchenwine |

| ante 604 to 616/7? | Sæberht | Son of Sledd |

| 616/7? to 623? | Sexred | Son of Sæberht. Joint king with Saeward and a third brother; killed in battle against the West Saxons |

| 616/7? to 623? | Saeward | Son of Sæberht. Joint king with Sexred and a third brother; killed in battle against the West Saxons |

| 616/7? to 623? | (another son of Sæberht, name unknown) | Joint king with Sexred and Saeward; killed in battle against the West Saxons |

| 623? to ante c. 653 | Sigeberht the Little | |

| c. 653 to 660 | Sigeberht the Good | Apparently son of Sæward. Saint Sigeberht; Saint Sebbi (Feast Day 29 August) |

| 660 to 664 | Swithhelm | |

| 664 to 683 | Sighere | son of a Sigeberht, probably 'the Good'. Joint-king with Sæbbi |

| 664 to c. 694 | Sæbbi | Son of Sexred. Joint-king with Sighere; abdicated in favour of his son Sigeheard |

| c. 694 to c. 709 | Sigeheard | Joint-king with his brother Swaefred[38] |

| c. 695 to c. 709 | Swæfred | Son of Sæbbi. Joint-king with his brother Sigeheard[38] |

| c. 709 | Offa | Son of Sighere. Joint-king during latter part of reign of Swæfred and perhaps Sigeheard. |

| c. 709? to 746 | Saelred | Representing distant line descended from Sledd. Probably joint-king with Swaefbert |

| c. 715 to 738 | Swæfbert | Probably joint-king with Saelred |

| 746 to 758 | Swithred | Grandson of Sigeheard |

| 758 to 798 | Sigeric | Son of Saelred. Abdicated |

| 798 to 812 | Sigered | Son of Sigeric. Mercia defeated by Egbert of Wessex, sub-kingdom of Essex subsumed into Wessex; from 812 to about 825 held it only as dux. |

Notes edit

- ^ The Latin name was used, for instance, by William of Malmesbury.

References edit

- ^ Keightley, Thomas (1842). The History of England: In two volumes. Longman.

- ^ a b c Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. Routledge. pp. 47–52. ISBN 978-1-134-70725-6.

- ^ Kings and Kingdoms of early Anglo-Saxon England, Chapter 3, Barbara Yorke, 1990, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16639-X

- ^ Baker, John T. (2006). Cultural Transition in the Chilterns and Essex Region, 350 AD to 650 AD. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-902806-53-2.

- ^ a b Rippon, Stephen, Essex c. 760 – 1066 (in Bedwin, O, The Archaeology of Essex: Proceedings of the Writtle Conference (Essex County Council, 1996)

- ^ Campbell, James, ed. (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin. p. 26.

- ^ H Hamerow, Excavations at Mucking, Volume 2: The Anglo-Saxon Settlement (English Heritage Archaeological Report 21, 1993)

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (1985). "The Kingdom of the East Saxons". In Clemoes, Peter; Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (eds.). Anglo-Saxon England 14. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–36.

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (1985). "The Kingdom of the East Saxons". In Clemoes, Peter; Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (eds.). Anglo-Saxon England 14. Cambridge University Press. p. 14.

- ^ Hooke, Della (1998). The Landscape of Anglo-Saxon England. Leicester University Press. p. 46.

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (2005) [1990]. Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and new York: Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

- ^ a b Andrew Reynolds, Later Anglo-Saxon England (Tempus, 2002, page 67) drawing on S Bassett (ed) The Origin of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (Leicester, 1989)

- ^ a b Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-134-70725-6.

- ^ Pewsey & Brooks, East Saxon Heritage (Alan Sutton Publishing, 1993)

- ^ a b c Hooke, Della (1998). The Landscape of Anglo-Saxon England. Leicester University Press. p. 47.

- ^ "VCH, volume 5".

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (1985). "The Kingdom of the East Saxons". In Clemoes, Peter; Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (eds.). Anglo-Saxon England 14. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–36.

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (1985). "The Kingdom of the East Saxons". In Clemoes, Peter; Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (eds.). Anglo-Saxon England 14. Cambridge University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (1985). "The Kingdom of the East Saxons". In Clemoes, Peter; Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (eds.). Anglo-Saxon England 14. Cambridge University Press. p. 16.

- ^ Metcalf, DM (1991). "Anglo-Saxon Coins 1". In Campbell, James (ed.). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin. pp. 63–64.

- ^ Details on the church, Colchester Archaeologist website https://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=34126

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 58. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ Bede, book II, chapter 3

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 109.

- ^ Yorke, Barbara, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England (1990)

- ^ Blair, I. 2007. Prittlewell Prince. Current Archaeology 207: 8-11

- ^ Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 114.

- ^ Bede, HE, III, 30, pp. 200–1.

- ^ a b Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 239

- ^ Travels in England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth by Paul Hentzner; Fragmenta Regalia by Sir Robert Naunton. 1892 Cassell https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1992/pg1992.html accessed 8.9.2021

- ^ "Essex archdeaconry through time". Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ Rippon, Stephen (1996). "Essex c.700 - 1066". In Bedwin, O (ed.). The Archaeology of Essex, proceedings of the Writtle conference. Essex County Council. p. 117. ISBN 9781852811228.

- ^ Brooke, Christopher Nugent Lawrence; Keir, Gillian (1975). London, 800-1216: the shaping of a city. University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780520026865.

- ^ Swanton, Michael, ed. (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. Phoenix Press. p. 60.

- ^ Sigeric 4 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved 2016-01-29.

- ^ a b Cyril Hart The Danelaw (The Hambledon Press, 1992, chapter 3)

- ^ Hart, Cyril (1987). "The Ealdordom of Essex". In Neale, Kenneth (ed.). An Essex Tribute. Leopard's Head Press. p. 62.

- ^ a b Handbook of British Chronology (CUP, 1996)

Bibliography edit

- Carpenter, Clive. Kings, Rulers and Statesmen. Guinness Superlatives, Ltd.

- Ross, Martha. Rulers and Governments of the World, Vol. 1. Earliest Times to 1491.

Further reading edit

- Rippon, Stephen (2022). Territoriality and the Early Medieval Landscape: the Countryside of the East Saxon Kingdom. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-680-6.