Summary

Kirkdale Cave is a cave and fossil site located in Kirkdale near Kirkbymoorside in the Vale of Pickering, North Yorkshire, England. It was discovered by workmen in 1821, and found to contain fossilized bones of a variety of mammals not currently found in Great Britain, including hippopotamuses (the farthest north any such remains have been found), elephants and cave hyenas.

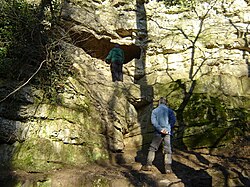

| Kirkdale Cave | |

|---|---|

Entrance to Kirkdale Cave | |

Showing location of Kirkdale Cave in North Yorkshire | |

| Location | Vale of Pickering, North Yorkshire, England |

| OS grid | SE 6784 8560 |

| Coordinates | 54°15′42″N 0°57′36″W / 54.261588°N 0.960088°W |

| Length | 436 metres (1,430 ft)[1] |

| Elevation | 58 metres (190 ft)[1] |

| Discovery | 1821 |

| Geology | Jurassic Corallian Limestone |

| Entrances | 1 |

| Access | Entrance is in face of old quarry |

William Buckland analyzed the cave and its contents in December 1821 and determined that the bones were the remains of animals brought in by hyenas who used it for a den, and not a result of the Biblical flood floating corposes in from distant lands, as he had first thought. His reconstruction of an ancient ecosystem from detailed analysis of fossil evidence was admired at the time, and considered to be an example of how geo-historical research should be done.

The cave was extended from its original length of 175 metres (574 ft) to 436 metres (1,430 ft) by Scarborough Caving Club in 1995. A survey was published in Descent magazine.[1]

Contents edit

The fossil bones found in the cave included elephants, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, hyenas, bison, giant deer, smaller mammals and birds.[2] Aside from the reported discovery of hippopotamus remains in Stockton-on-Tees,[3] this is the northernmost site in the world where hippopotamus remains have been found.[4] It also included a considerable amount of fossilized hyena faeces. The fossilized remains were embedded in a silty layer sandwiched between layers of stalagmite.[5]

Discovery and analysis edit

The discovery at Kirkdale occurred in the wake of new forms of stratigraphic dating developed during the Enlightenment.[6] As was the case for many nineteenth century fossils, the bones in Kirkdale were originally found by local inhabitants. The entrance to the cave was found by limestone quarry workers in the summer of 1821. The quarry workers assumed that the abundant bones buried in the cave floor were the remains of cattle that had been dumped in the cave after dying from some past epidemic. They used some of the bones to fill potholes in a nearby road, where an amateur naturalist noticed them and realized that they were not the remains of livestock. This attracted the attention of numerous fossil collectors. Some of the fossils were sent to William Clift the curator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons; he identified some of the bones as the remains of hyenas larger than any of the modern species. At the same time, William Buckland was told about the cave and shown some of the fossils by a colleague at Oxford.[5]

Buckland began his investigation believing that the fossils in the cave were diluvial, that is that they had been deposited there by a deluge that had washed them from far away, possibly the Biblical flood. Upon further investigation, he realized the cave had never been open to the surface through its roof, and that the only entrance was too small for the carcasses of animals as large as elephants or hippos to have floated in. He began to suspect that the animals had lived in the local area, and that the hyenas had used the cave as a den and brought in remains of the various animals they fed on. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that many of the bones showed signs of having been gnawed prior to fossilization, and by the presence of objects which Buckland suspected to be fossilized hyena dung. Further analysis, including comparison with the dung of modern spotted hyenas living in menageries, confirmed the identification of the fossilized dung.[5]

He published his analysis in an 1822 paper he read to the Royal Society.[7] A few days before reading the formal paper, he gave the following colourful account at a dinner held by the Geological Society:

The hyaenas, gentlemen, preferred the flesh of elephants, rhinoceros, deer, cows, horses, etc., but sometimes, unable to procure these, & half starved, they used to come out of the narrow entrance of their cave in the evening down to the water's edge of a lake which must once have been there, & so helped themselves to some of the innumerable water-rats in wh[ich] the lake abounded.[8]

He developed these ideas further in his 1823 book Reliquiae Diluvianae; or, Observations on the organic remains contained in caves, fissures, and diluvial gravel, and on other geological phenomena, attesting the action of an universal deluge, challenging the belief that the bones were brought to the cave by Noah's flood and providing detailed evidence that instead hyenas had used the cave as a den into which they brought the bones of their prey.[9]

Calcite deposits overlying the bone-bearing sediments have been dated as 121,000 ± 4000 yr BP using uranium-thorium dating, confirming that the material dates from the Ipswichian interglacial.[10]

Impact and legacy edit

The specimens were an original part of the archaeology collection of the Yorkshire Museum and it is said that "the scientific interest aroused founded the Yorkshire Philosophical Society".[11] While criticized by some, William Buckland's analysis of Kirkland Cave and other bone caves was widely seen as a model for how careful analysis could be used to reconstruct the Earth's past, and the Royal Society awarded William Buckland the Copley Medal in 1822 for his Kirkdale paper.[5] At the presentation the society's president, Humphry Davy, said:

by these inquiries, a distinct epoch has, as it were, been established in the history of the revolutions of our globe: a point fixed from which our researches may be pursued through the immensity of ages, and the records of animate nature, as it were, carried back to the time of the creation.[12]

Region edit

The cave is a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a Geological Conservation Review site.

The Saxon St Gregory's Minster with its unusual sundial is nearby.

References edit

- ^ a b c Monico, Paul (December 1997 – January 1998). "Beyond the unexplored extremity". Descent (139): 27.

- ^ MY learning: Learning with Museums, Libraries and Archives in Yorkshire. "Ideas and Evidence in Science: The Kirkdale Cave: Discovery of the cave". Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "The 'Stockton Hippo': 5 questions answered by university professor". Stockton Borough Council. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Natural England. "SSSI citation details for Kirkdale cave" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d Rudwick, Martin Bursting The Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (2005) pp. 622–638

- ^ Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2008). The Language of Mineralogy: John Walker, Chemistry and the Edinburgh Medical School, 1750–1800. London: Ashgate. p. See esp. Ch. 5.

- ^ a b Rudwick, Martin Scenes from Deep Time (1992) pp. 38–42

- ^ Rudwick, Martin Bursting The Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (2005) p. 630

- ^ Oxford University Museum of Natural History. "Learning more:William Buckland" (PDF). p. 3. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ McFarlane, Donald; Ford, Derek (April 1998). "The Age of the Kirkdale Cave Palaeofauna". Cave and Karst Science. 25 (1). British Cave Research Association: 3–6.

- ^ MY learning: Learning with Museums, Libraries and Archives in Yorkshire. "Ideas and Evidence in Science: The Kirkdale Cave: Book that changed the world". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin Bursting The Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (2005) p. 631

External links edit

- SSSI details from Natural England

- GCR details from Joint Nature Conservation Committee