Summary

Paul Mactire, also known as Paul MacTyre, and Paul M'Tyre, was a 14th-century Scotsman who lived in the north of Scotland. He appears in several contemporary records, as well as in a 15th-century genealogy which records his supposed ancestry. He is known to have married a niece of the brother of the Earl of Ross. According to later tradition, he was a notorious robber, or freebooter in the north of Scotland;[1] and, according to local tradition, he was the builder of a now ruinous fortress in Sutherland. He is said to be the ancestor of several Scottish families. According to some sources Paul Mactire's father was Leod Macgilleandrais.

Paul Mactire | |

|---|---|

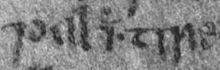

Paul's name as it appears in the 15th century MS 1467. | |

| Spouse(s) | Mary/Mariot of Graham (niece of Hugh of Ross, Lord of Fylorth) |

| Children | Catharene (daughter) |

| Notes | |

Paul's wife is recorded in a charter, his daughter is known from later tradition. | |

Contemporary records edit

In 1365, Hugh of Ross, Lord of Fylorth, the brother of William III, Earl of Ross, granted to the lands of "Tutumtarvok", "Turnok", "Amot", and "Langville", in "Strathokel", to Paul and his wife, "Mariot of Graham", and their lineal descendants. Paul's wife was the niece of Hugh.[2] The next year, William, Earl of Ross, granted the lands of Gairloch to Paul and his heirs by "Mary of Grahame", with remainder to the lawful heirs of Paul, for the annual payment of a silver penny in name of blench ferme, in lieu of all services, except forinsee service to the king if required. In 1372, the grant was confirmed by Robert II.[3][4]

MS 1467 edit

Paul appears in the 15th century MS 1467, as a descendant of Clan Gillanders.[5] Skene's transcription, and translation, of the genealogy of the clan is as follows:

| Skene's mid 19th century transcription of the Gaelic | Skene's mid 19th century translation into English |

|---|---|

| Pal ic Tire ic Eogan ic Muiredaigh ic Poil ic Gilleanris ic Martain ic Poil ic Cainig ic Cranin ic Eogan ic Cainig ic Cranin mc Gilleeoin ha hairde ic Eirc ic Loirn ic Fearchar mc Cormac ic Airbertaig ic Feradaig.[6][note 1] | Paul son of Tire son of Ewen son of Murdoch son of Paul son of Gilleanrias son of Martin son of Paul son of Kenneth son of Crinan son of Ewen son of Kenneth son of Crinan son of Gilleoin of the Aird son of Erc son of Lorn son of Ferchar son of Cormac son of Oibertaigh son of Feradach.[8] |

| Skene's late 19th century transcription of the Gaelic | Skene's late 19th century translation into English |

| Pal mac Tire mhic Eogain mhic Muredaig mhic Poil mhic Gilleainnrias mhic Martain mhic Poil mhic Cainnig mhic Cristin mhic Eogain mhic Cainnig mhic Cristin mhic Gillaeoin na hairde mhic Eirc mhic Loairn mhic Cormac mhic Airbertaigh mhic Fearadhach.[9] | Paul son of Tire son of Ewen son of Muredach son of Paul son of Gillandres son of Martin son of Paul son of Kenneth son of Cristin son of Ewen son of Kenneth son of Cristin son of Gillaeoin of the Aird son of Erc son of Lorn son of Ferchard son of Cormac son of Airbertach son of Feradach.[9] |

The MS 1467 records that Paul's great-great-grandfather was Gillanders, who was in turn eight generations in descent from Gilleoin of the Aird, who is also recorded within the manuscript as the progenitor of the Mackenzies and the Mathesons. Gilleoin of the Aird is thought to have flourished around 1140, and is thought to have governed a large expanse of land in the north of Scotland, independent of the 12th century mormaers of Moray. According to Alexander Grant, he is likely to have filled the vacuum in southern Ross, left by the reduction of Norse power in the later part of the 11th century.[5]

According to Skene, this manuscript shows that Paul descended from a brother of Fearchar, Earl of Ross.[10] W. D. H. Sellar pointed out that there are too many generations between Paul and Gilleoin of the Aird. Sellar considered that the genealogy combined the descendants of Gilleoin of the Aird with the ancestors of Paul; thus, that the genealogy should actually start with the Paul who appears in the manuscript as Gillander's grandfather. However, according to William Matheson, it is possible that this Paul is Páll Bálkason, a 13th-century sheriff of Skye. Matheson considered that Páll Bálkason's father was an ancestor of the MacPhails, MacKillops, and the MacLeods.[5][note 2]

According to the 19th-century historian Alexander Mackenzie, Paul's name Mactire stands for the Gaelic Mac an t'Oighre, meaning "son of the Heir";[11] although the 20th century etymologist George Fraser Black thought this a "wild statement".[12] According to early 20th century Gaelic scholar Alexander Macbain, the Tyre in Paul's name does not mean "Paul, son of Tyre", but rather "Paul the Wolf". Macbain stated that the Gaelic name Mac'ic-tire was a common one during Paul's era, and that the stories of his harrying of Caithness may have contributed to his bearing such a name.[13] Black gave the name's derivation from the Irish mac tire, meaning "son of the soil (wolf)".[12] Later, William Matheson also considered Mactire to be a byname; although, Sellar stated that it was unclear whether it was a byname or a patronymic name.[5]

Manuscript history of the Rosses of Balnagown edit

The manuscript history of the Rosses of Balnagown states that a King of Denmark had three sons who came to the north of Scotland: "Gwine", "Loid", and "Leandres".[14] The manuscript states that Gwine conquered the braes of Caithness; Loid conquered Lewis, and was the progenitor of the MacLeods; and Leandres conquered "Braychat".[14] The 19th century antiquary F. W. L. Thomas noted that Braychat referred to Strathcarron. Thomas considered the "King of Denmark" to be mythological, and proposed that the king likely refers to Sveinn Ásleifarson, a prominent character in the mediaeval Orkneyinga saga. Thomas noted that in the saga, Sveinn's brother as named Gunni; Sveinn's son was named Andreas. Thomas also noted that in the saga, Sveinn was the friend of a man named Ljótólfr, from Lewis;[15] and Thomas considered Ljótólfr to have been an ancestor of the MacLeods.[16][17] According to W. F. Skene, Gwine was probably meant to refer to the eponymous ancestor of Clan Gunn.[18] According to Sellar, Denmark should not be taken literally: in this context, Denmark likely stands for Scandinavia.[19]

The manuscript states that the son of Leandres was "Tyre", whose son was "Paul M'Tyre", and that this Paul M'Tyre was the founder of "Clan Lendres" because his daughter, "Catharene", married the laird of Balnagown, Walter Ross.[14] As earlier as the 17th century, the Rosses were stated to be known in Ross as 'Clan Gillanders'.[5][note 3] The manuscript states that Caithness paid Paul M'Tyre blackmail, and that it was said that he took annually 180 cattle. According to the manuscript, Paul had two sons, "Murthow Reoche", and "Gillespik". It relates how Murthow Reoche was slain at "Spittalhill", between Yule and Candlemas, while on a trip to Caithness to collect the blackmail; when Gillespik heard of his brother's death, he returned home to Ross.[14]

Chief of Clan Ross edit

It is thought that the first five chiefs of Clan Ross held the title of Earl of Ross, starting with Fearchar.[20] On the death of the fifth chief, William III, Earl of Ross (d.1372),[21] the title passed through an heiress to a member of Clan Leslie.[20] With the extinction of the man line in the fifth earl, the leadership of the Rosses passed into the line of the Rosses of Balnagown.[21] From studying the MS 1467, Skene believed that Paul became chief of Clan Ross immediately following the death of the fifth chief.[10] Mackenzie noted that the Rosses were long known in Gaelic as "Clann Gille Ainnrais" (Clan Gillanders), and that the MS 1467 shows that Paul was the chief of this clan; in consequence, Mackenzie like Skene before him, considered that Paul's clan in the manuscript referred to the Rosses. Mackenzie stated that the tradition of Paul taking leadership of the Clan Ross was also collaborated by the charter he received from William III, in which Paul is styled as the earl's cousin.[22] According to Skene, the MS 1467 shows that Clan Gillanders descended from a brother of Fearchar,[10] and Mackenzie stated that Fearchar was the son of Gillanders, eponymous ancestor of the clan.[22] Skene noted that the traditional ancestry of the Rosses of Balnagown stated that they descended from Paul through his daughter. However, according to Skene, "when a family is led by circumstances to believe in a descent different from the real one, we invariably find that they assert a marriage between their ancestor and the heiress of the family from which they are in reality descended".[10]

Other traditions concerning Paul and his daughter edit

In the late 18th century, the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant, toured the north of Scotland and wrote of his travels. Included within his description of the parish of Creich, in Sutherland, Pennant wrote of a tradition concerning Paul, and the marriage of his daughter.

In the 11th or 12th century lived a great man in this parish, called Paul Meutier. This warrior routed an army of Danes near Creich. Tradition says that he gave his daughter in marriage to one Hulver, or Leander, a Dane; and with her, the lands of Strahohee; and that from that marriage are descended the Clan Landris, a brave people, in Rosssshire [sic].[23]

In the mid 19th century, Alexander Pope translated Þormóður Torfason's 17th century Latin history of Orkney. A figure who is portrayed in Þormóður Torfason's account is a violent character named "Aulver Rosta". Pope postulated that this character was the man who married the daughter of Paul Mactire.

As for Aulver Rosta, the author [Þormóður Torfason] gives no further account of him, but it is probable he was the same person that married Paul Mactier's daughter, and got with her the lands of Strath Okel; for he is called a Dane or Norweigian [sic], and Aulver is the same name with Leander. The Paul was a powerful man that lived in Sutherland. It is a common tradition, that Paul Mactier gave the lands of Strath Okel as a patrimony to his daughter, who was married to a nobelman [sic] of Norway, called Leander. His posterity are called Clan Landus.[24]

Places associated with Paul edit

Sometime before 1630, Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonstoun wrote an historical account which mentioned Paul. Gordons wrote that the ruinous fortress of Dun Creich was built by Paul, who possessed the lands of Creich. Gordonstoun stated that Paul built the fortress with a hard mortar which could not be identified even at the time of his writing, in the 17th century. Gordonstoun stated that, while Paul built the fortress, he heard of the news of the killing of his only son in Caithness. At the time of his death, Paul's son had been in the company of an outlaw named "Murthow Raewick". Upon learning of his son's death, Paul ceased the building of Dun Creich. Gordonstoun also noted that there were many things 'fabulously reported among the vulgar people' that he did not relate to. John Jamieson, writing in the early 19th century, stated that this account of the construction of Dun Creich should not be taken seriously. Jamieson proposed that this tradition may be the earliest one to attempt to explain its construction, and that the hard mortar supposedly used by Paul, was an attempt to explain a vitrified fort. Jamieson proposed that the memory of Paul in the area, may have led the locals to connect him to the fortress, and attempt to explain its unfinished state.[25]

In the late 19th century, William Taylor stated that a spot near Tain, on the shores of Fendom, was known as Paul MacTyre's Hill. Taylor noted that the place had been washed away by the sea in the previous century.[26] The 20th-century Scottish toponymist William J. Watson noted that there was a place, located near Plaids (near Tain), where there was said to have been a court-hill of Paul.[27] Watson stated that Lochan Phòil, meaning "Paul's lochlet", is probably named after Paul, who held the surrounding lands.[28]

Supposed descendants edit

According to tradition, Paul was an ancestor of the Rosses of Balnagown (in the female line).[29] According to Macbain, the surname Polson was in the Creich area sometime before the year 1430; and listed two instances of the surname in the area in the mid 16th century. Macbain noted that the 19th century antiquary Cosmo Innes stated that this family was descended from Paul, who is recorded as acquiring the lands by charter, in 1365.[30] However, Black stated that Paul is wrongly assumed to have been the ancestor of the Polsons.[12] Sellar noted that some of the descendants of Paul took the surname Fraser, and became the barons of Moniack. Sellar noted that it was said that some of these Frasers later took the surname Barron and lived in the district of Aird.[19]

See also edit

- Leod Macgilleandrais, said to have been the father of Paul Mactire in the late 19th, and early 20th centuries

Notes edit

- ^ Skene stated, in his late 19th century Celtic Scotland, that judging from the generations within the MS 1467, Cormac mac Airbertach would appear to have lived in the 10th century, but the man represented as his father, Airbertach, is given as the son of Feradach, and brother of Ferchar Fota who died in 697. Skene considered many of the early generations represented in the pedigrees of various clans within the MS 1467 to be unreliable.[7]

- ^ Sellar disagreed with Matheson's assertion that the MacLeods descended in the male-line from Páll Bálkason.[5]

- ^ Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonstoun stated that "all the Rosses in that province ar unto this day called in the Irish language Clan Leamdreis".[5]

References edit

- Footnotes

- ^ Watson 1904: pp. 12–14.

- ^ Origines parochiales Scotiae: p. 411.

- ^ Origines parochiales Scotiae: p. 406.

- ^ Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis: p. 62 footnote 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grant 2000: pp. 113–115.

- ^ Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis: p. 54.

- ^ Skene 1899: pp. 344–346.

- ^ Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis: p. 55.

- ^ a b Skene 1899: pp. 484–485.

- ^ a b c d Skene 1902: pp. 322–325.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: p. 39.

- ^ a b c Black 1946: p. 567.

- ^ Skene 1902: p. 417.

- ^ a b c d Baillie 1850: pp. 30–32.

- ^ Thomas 1879–80: pp. 375–379.

- ^ Thomas 1879–80: pp. 369–370, 379.

- ^ "The Origin of Leod". www.macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2010. This webpage cited: Morrison, Alick (1986). The Chiefs of Clan MacLeod. Edinburgh: Associated Clan MacLeod Societies. pp. 1–20.

- ^ Skene 1899: pp. 354–355.

- ^ a b "The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered". www.macleodgenealogy.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2010. This webpage cited: Sellar, W.D.H. (1997–1998), "The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered", Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, 60: 233–258

- ^ a b Roberts 1997: p. 85.

- ^ a b Moncreiffe of that Ilk 1967: pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Mackenzie 1878: pp. 42–44.

- ^ Pennant 1769: pp. 360–361.

- ^ Pope 1866: pp. 131–132.

- ^ Jamieson 1834: pp. 227–251.

- ^ Taylor 1882: pp. 29–30.

- ^ Watson 1904: p. 34.

- ^ Watson 1904: p. 18.

- ^ Mackenzie 1894: p. 37.

- ^ Macbain 1922: p. 22.

- Bibliography

- The Bannatyne Club, ed. (1851), Origines Parochiales Scotiae: The Antiquities Ecclesiastical and Territorial of the Parishes of Scotland, vol. 2, part 2, Edinburgh: W. H. Lizars

- The Iona Club, ed. (1847), Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis: consisting of original papers and documents relating to the history of the highlands and islands of Scotland, Edinburgh: Thomas G. Stevenson

- Baillie, W.R., ed. (1850), Ane Breve Chronicle of the Earlis of Ross, including notices of The Abbots of Fearn, and of The Family of Ross of Balnagown, Edinburgh

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Black, George Fraser (1946), The Surnames of Scotland: Their Origin, Meaning, and History, New York: New York Public Library

- Grant, Alexander (2000), "The Province of Ross and the Kingdom of Alba", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, R. Andrew (eds.), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-86232-151-5

- Jamieson, John (1834), "On the Vitrified Forts of Scotland", Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom, vol. 2, London: John Murray

- Macbain, Alexander (1922), Place names, Highlands & islands of Scotland, With notes and a foreword by William J. Watson, Stirling: Eneas Mackay

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1878), "History of Clan Mackenzie", in Mackenzie, Alexander (ed.), The Celtic Magazine: A Monthly Periodical devoted to the Literature, History, Antiques, Folk Lore, Traditions, and the Social and Material Interests of the Celt at Home and Abroad, vol. 3, Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1894), History of the Mackenzies: With Genealogies of the Principle Families of the Name (New, revised, and extended ed.), Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk, Iain (1967), The Highland Clans, London: Barrie & Rockliff

- Pennant, Thomas (1769), A Tour in Scotland: MDCCLXIX (4th ed.), London: Printed for Benjamin White

- Roberts, John Leonard (1997), Lost Kingdoms: Celtic Scotland and the Middle Ages, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-585-06082-8

- Skene, William F. (1899), Celtic Scotland: a history of Ancient Alban, vol. 3 (2nd ed.), Edinburgh: David Douglas

- Skene, William F. (1902), Macbain, Alexander (ed.), The Highlanders of Scotland, Stirling: Eneas Mackay

- Taylor, William (1882), Researches into the History of Tain: Earlier and Later, Tain: Alexander Ross

- Torfæus, Thormodus (1866), Pope, Alexander (ed.), Ancient History of Orkney, Caithness, & the North, Wick: Peter Reid

- Thomas, F.W.L. (1879–80), "Traditions of the Macaulays of Lewis" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 14

- Watson, William J. (1904), Place names of Ross and Cromarty, Inverness: The Northern Counties Printing and Publishing Company