Summary

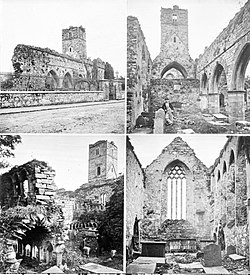

Sligo Abbey (Irish: Mainistir Shligigh[2]) was a Dominican convent in Sligo, Ireland, founded in 1253.[3][4] It was built in the Romanesque style with some later additions and alterations. Extensive ruins remain, mainly of the church and the cloister.

| |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Dominican Order |

| Established | 1253 |

| Disestablished | 1760 |

| Diocese | Elphin |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Maurice Fitzgerald, Baron of Offaly |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Norman, Gothic |

| Site | |

| Location | Sligo, County Sligo |

| Public access | Yes |

| Official name | Sligo Abbey |

| Reference no. | 189[1] |

The site is managed by the Office of Public Works and opens on a seasonal basis - March 17th to November 5th is the 2023 season. Sligo Abbey is open daily from 10.00 am - 6.00 pm, with last admissions at 5.15 pm.[4]

Name and location edit

The name "Sligo Abbey" is the generally accepted traditional name, but strictly speaking "abbey" is inappropriate as Dominican monasteries are led by priors not abbots: "convent", "friary", or "priory" would be more correct. The community was dedicated to the Holy Cross. The ruins are located in Abbey Street, Sligo, but when it was still functioning, the convent lay outside the town's limits and its location was then usually described as "near Sligo".[5]

History edit

Sligo Abbey, was a Dominican Friary, founded in 1253 by Maurice FitzGerald, 2nd Lord of Offaly,[6] who was Justiciar of Ireland from 1232 to 1245.[7] His purpose allegedly was to house a community of monks to pray for the soul of Richard Marshal, 3rd Earl of Pembroke,[8] whom he was rumoured to have killed. The Dominicans were a poor choice for such a task as their specialty is preaching rather than praying. FitzGerald built a substantial Norman abbey, with all the essential parts and endowed it with lands.[9]

In 1414 the buildings were damaged in an accidental fire. The abbey did not have sufficient means for the reconstruction and appealed to the pope for help.[10] At that moment three men competed with each other in the Vatican Standoff: Benedict XIII was pope in Avignon, Gregory XII in Rome, and John XXIII in Pisa. As England supported John, this was the pope the abbey addressed. Their letter reached John at the Council of Constance (1414–1418). John replied by sending an apostolic letter from Constance granting indulgences of ten years to all who would visit the church on the feast of the Assumption and the day of Saint Patrick and contribute to its restoration. The friary was rebuilt in 1416 by Prior Brian, son of Dermot MacDonagh,[11] tanist (prince) of Tirerrill and Collooney. There were 20 friars at the abbey at that time.[12]

When the Dissolution of the Irish monasteries that had started in 1530 in the Pale, began to menace monasteries in the West of Ireland, Donogh O'Connor Sligo in 1568 obtained a letter from Queen Elizabeth that exempted Sligo Abbey on condition that the friars would become secular priests.[13]

During Tyrone's Rebellion (1594–1603) the abbey was damaged when Richard Bingham, president of Connaught, besieged Sligo Castle in 1595,[14][15] which was held by Hugh Roe O'Donnell's men.[16] Bingham stationed six companies of troops and horses in the Abbey, and dismantled the rood screen, using it and other timber from the building to build a siege tower for his unsuccessful attack on the castle. After the war, at the beginning of the 17th century, the abbey and its lands were granted to Sir William Taaffe in consideration of his services to Queen Elizabeth.[17] Sir William was the grandfather of Theobald Taaffe, 1st Earl of Carlingford.[18]

In 1608 only one friar was left in the abbey, Father O'Duane, who died in this year. However, Father Daniel O'Crean arrived from Spain before O'Duane's death and built up a new community,[19] succeeding so well that in 1627 Ross MacGeoghegan, provincial of the Dominical Order in Ireland, held a provincial chapter in Sligo.[20]

During the Irish Confederate Wars (1641–1653) the convent was attacked and burned by Sir Frederick Hamilton in the summer of 1642.[21][22] Some of the friars were killed.[23]

In 1697 when King William reigned alone, the Irish Parliament passed the Banishment Act, which specified that all ordinaries (bishops) and regular clergy (e.g. monks) must leave the country before 1 May 1698. It did not affect the parish priests, who are classified as secular priests. The Dominicans of Sligo left Ireland for Spain, led by their prior, Father Patrick McDonogh. The abbey stood then empty.[24]

In the 18th century some friars came back to Sligo and stayed in the abbey. In 1760 when Father Lawrence Connellan returned from Louvain to Sligo, he found that the buildings had deteriorated so far that it was necessary to find other accommodation. In 1783 he obtained a lease in High Street and moved there.[25] In the second half of the 18th century, the friars built a chapel in Pound Street.[26] In 1803 a new friary was built.[27] In 1846 Father B. J. Goodman, prior of the friary and provincial of the order, built the Neogothic Holy Cross Church in High Street,[28] and in 1865 another residence for the friars was built behind that church in Dominick Street.[29]

The abbey grounds were used as cemetery. The buildings were quarried for reusable stone. In 1893 Evelyn Ashley, to whom the abbey had come from Lord Palmerston, vested part of it in the Board of Works and the rest followed in 1913, donated by his son Wilfrid William Ashley.[30] The Board then did work on the ruins, freeing them from ivy, bushes and trees growing on it.[31]

| Timeline | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1253 | Founded by Maurice FitzGerald, 2nd Lord of Offaly.[6] | |

| 1414 | Accidentally burned.[10] | |

| 1416 | Restored.[11] | |

| 1568 | Donogh O'Connor Sligo obtained from Queen Elizabeth the exemption from the dissolution of the monasteries.[13] | |

| 1595 | Damaged in the siege of Sligo Castle by George Bingham during Tyrone's Rebellion.[14] | |

| c. 1603 | Granted to William Taaffe, who allowed the friars to stay.[17] | |

| 1642 | Attacked and burned by Frederick Hamilton during the Irish Confederate Wars.[21] | |

| 1698 | The friars left for Spain after the Banishment Act.[24] | |

| c. 1770 | The friars built a chapel in Pound Street.[26] | |

| 1846 | The Dominicans built the Holy Cross Church in High Street.[28] | |

| 1913 | The abbey ruins become possession of Board of Works.[30] | |

Architecture edit

The abbey ruins consist of the walls of the church, inclusive those of the tower, three sides of the cloister, and remains of the sacristy, the chapter room, the refectory, and the dormitories. Most of the buildings seem to date from the 13th century, the time of the monastery's foundation and were built in a late romanesque or more specifically Norman Style. In the 15th century late Gothic additions and replacements were made and some others in the 16th century.

The church was never vaulted and, having lost its wooden roof, stands open to the sky. The church's walls are 3 feet 7 inches (1.09 m) thick[32] and their tops are covered with water tables and crowned with ruinous parapets that might once have been crenulated.[33] The church is divided into the choir (or chancel) in the east and the nave in the west by the 15th-century cut-stone rood screen, that consisted of a gallery across the church supported by ribbed groin vaults, three bays wide and one deep. This rood screen has been partially reconstructed from its surviving right and left abutments in the abbey's latest restoration (see photo).[34]

The tower is another 15th-century addition. It is thick-walled and square. It is placed on the main axis of the church just east of the rood screen and suspended over the church by the means of two lofty pointed and profiled arches forming an archway or tunnel that connects the two parts of the church. The underside of the tower is closed by a ribbed and groined fan vault. The tower has a door on its north side that was reached over the roof. With the roof gone, the tower has become inaccessible. The tower resembles those of Kilcrea Friary, Muckross Abbey, Quin Abbey, and Rosserk Friary, but none of those is as daringly suspended.

The church's east end is square. The terminal wall holds a large late-Gothic window divided into four lights by mullions. Its head is filled with reticular tracery. This window must have replaced one or several Romanesque windows in the 15th century. In front of this window stands the table of the high altar, the front of which is divided into nine panels decorated with late-gothic cusped arches and foliage in relief. This altar also dates from the Late Gothic.[35]

The nave has the same width as the choir. Its western façade has been destroyed so that the western end of the church stands open. On the southern side the nave was accompanied by an aisle and a one-armed transept (or lateral chapel). Both are later additions. The aisle has been entirely demolished and the transept partially, so that the arcade, consisting of three pointed arches supported by octagonal pillars, is exposed. The transept once held two altars. The naves of Kilcrea Friary, Muckross Abbey, Quin Abbey, and Rosserk Friary have similar one-armed transepts.

The cloister lies to the north of the church as is also the case at Kilcrea Friary, Moyne Abbey, Muckross Abbey, Quin Abbey, and Rosserk Friary.[36] The cloister's southern walk runs along the northern wall of the church's nave. Only three sides of the cloister remain standing; the western side has been demolished. The cloister walk is covered with rubble barrel vaults. Its arcades are supported by slender pillars reminiscent of double columns. The arches of the arcades and the barrel vaults are slightly pointed. The cloisters of Moyne Abbey and Quin Abbey have similar pillars and vaults. Despite its Romanesque appearance the cloister is attributed to the 15th century.[37]

The sacristy, vestry, and chapter room are in the ground floor of the east range. Excepted the western extension of the chapter room, they are part of the 13th-century core of the abbey.[38] They are covered with rubble barrel vaults similar to those of the cloister. The refectory occupied the first floor of the north range. Only its southern wall above the arcade of the cloister is preserved. From this wall protrudes a ruined oriel window giving light to the reader's desk where a friar would read aloud from the scriptures during mealtimes.[39]

Monuments edit

The church contains two noteworthy funeral monuments: the "O'Craian altar tomb" and the mural in remembrance of "Sir Donogh O'Connor Sligo". O'Craian's tomb is the oldest surviving monument in the church. Its Latin inscription dates it from 1506 and states that it is the tomb of Cormac O'Craian (or Crean) and his wife Johanna, daughter of Ennis (or Magennis). It fills a niche in the northern wall of the nave next to the rood screen. It consists of a stone table, similar to the altar in the choir, and a canopy consisting of a high pointed arch with tracery. The style is late Gothic.[40]

The O'Connor mural is on the wall of the choir to the right of the altar. It shows reliefs of O'Connor and his wife kneeling in prayer in an architectural frame, decorated with heraldic and religious motives.[41] Sir Donogh O'Connor obtained the letter from Queen Elizabeth that saved the abbey from dissolution, mentioned above. He died in 1609. His wife, Eleanor Butler, daughter of Lord Dunboyne, erected the monument in 1624 in a late Renaissance style. Before O'Connor she had been married to Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Desmond, who was killed in 1583.[42]

In popular culture edit

Sligo Abbey appears in two short stories by William Butler Yeats: The Crucifixion of the Outcast and The Curse of the Fires and of the Shadows. In both stories, the head of the monastery is called the abbot.[43][44] It is also the subject of what is possibly the oldest surviving painting of any building in Ireland.[45]

See also edit

-

Inside the cloister-walk

-

The late Gothic east window

-

Refectory window above the cloister

-

The O'Craian monument

-

The O'Connor Mural

Notes edit

- ^ "National Monuments of County Sligo in State Care" (PDF). heritageireland.ie. National Monument Service. p. 3. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ "Mainistir Shligigh | Oidhreacht Éireann". heritageireland.ie. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Visit Sligo Abbey with Discover Ireland". Discover Ireland. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Sligo Abbey | Heritage Ireland". heritageireland.ie. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ O'Rorke 1890, p. 245: "... even so late as the middle of the seventeenth century, it was spoken of as situated 'near Sligo' ..."

- ^ a b Smith 2004, p. 833, left column: "In 1253 he founded a Dominican friary in the town [i.e. Sligo]."

- ^ Fryde et al. 1986, p. 161.

- ^ Webb 1878a, p. 181, left column: "In 1236 he founded the Dominican Abbey at Sligo as the abode of a community of monks to say prayers for the Earl Marshal's soul ..."

- ^ Bell 1829, p. 241, line 2: "It owes its erection to the munificence of Maurice FitzGerald, who endowed it 1252."

- ^ a b Bell 1829, p. 241, line 7: "Having been consumed by an accidental fire in the year 1414, it was rebuilt in 1416, partly by the bounty of Bryan Mac Dermott McDonagh, and partly by votive contributions."

- ^ a b O'Rorke 1890, p. 275: "2. Brian, the son of Dermot McDonogh, as we have seen, was Prior in 1416 when the convent was restored after the burning;"

- ^ Wood-Martin 1882, p. 195, line 2: "... in which it is affirmed twenty brethren have devoutly served God ..."

- ^ a b Cochrane 1914, p. 1, line 14: "In 1568 on the petition of O'Connor Sligo, who pointed out that his ancestors were buried in the Abbey, Queen Elizabeth exempted it from dissolution, under the condition that the friars were converted into secular priests."

- ^ a b Cochrane 1914, p. 1, line 20: "In 1595 George Bingham, brother of the President of Connaught took possession of the abbey while besieging the neighbouring castle, and used much of the woodwork for making engines for the siege. Much damage was done to the building at this time."

- ^ Wood-Martin 1882, p. 342: "Bingham ... for the purpose of breeching the castle walls, commenced the construction of an engine in ancient parlance termed a 'sow;' it was formed of thick planks and rafters, which were taken from the dormitories of the monks; from the latticed screen in the Abbey ..."

- ^ Coleman 1902, p. 98: "In 1595, however, George Bingham, brother of the president of Connaught, took up his quarters in the abbey when he was besieging O'Donnell's warders who were in the castle, and ordered an engine to be constructed for demolishing it."

- ^ a b Taaffe 1958, p. 57: "... he [Sir William] distinguished himself in the service of Queen Elizabeth in the Irish wars, and as a reward received from Her Majesty and King James I large grants of land ... including ... the Abbey and abbey lands of Sligo."

- ^ Webb 1878b, p. 513: "... was grandson of the preceding [i.e. William]."

- ^ Coleman 1902, p. 99, line 6 : "In 1606, the only dominican left in sligo was Father O'Duane, who died that year, but before he closed his eyes in death, Father Daniel O'Crean arrived from Spain ..."

- ^ Coleman 1902, p. 37: "In 1627, he [Father Ross MacGeoghegan] held a provincial chapter in Sligo."

- ^ a b Wood-Martin 1882, p. 195, line 38: "It was burned ... by Sir Frederick Hamilton 22th August 1642."

- ^ O'Rorke 1890, p. 155: "The irruption of Hamilton into Sligo took place on the night of the 1 July, 1642."

- ^ Coleman 1902, p. 99, line 30: "... to the Friary, burned the superstitious trumperies ... the Fryars themselves were also burnt, and two of them running out were killed in their habits."

- ^ a b O'Rorke 1890, p. 282: "... in 1698, when William alone was on the throne, took place the final break-up of the establishment ..."

- ^ Wood-Martin 1892, p. 130, line 7: "... in 1760 ... Laurence Connellan ... returned to Sligo and saw the necessity of vacating the crumbling abbey and securing a more suitable situation. In 1783 he obtained a lease ..."

- ^ a b Coleman 1902, p. 100, line 28: "A neat little chapel was erected at the back of the houses in Pound Street, in the latter half of the eighteenth century."

- ^ Wood-Martin 1892, p. 130, line 15: "The friaary of the order of Saint Dominick was built in 1803 by Father Thomas Brennan ..."

- ^ a b Wood-Martin 1892, p. 130: "The present church of Holy Cross ... is in High-street and was erected about the year 1846 ..."

- ^ Coleman 1902, p. 100, line 36: "The present convent was finished and occupied by the fathers in 1865."

- ^ a b Cochrane 1914, p. 1, line 34: "After the dissolution the Abbey was granted to Sir William Taffe, and it eventually became, with other lands in Sligo, the property of the late Lord Palmerston, who spent some money on repairs and renovation. After his death, his kinsman, the late Hon. Evelyn Ashley, vested in the Board, in December 1893, portion of the Abbey. In July 1913, the present owner, Mr Wilfred W Ashley, M.P., vested the entire structure in the Board."

- ^ Cochrane 1914, p. 15: "The work done at Sligo Abbey during the year under review [1913] comprised the removal of ivy and elder bushes from the walls ..."

- ^ Cochrane 1914, p. 1, line 51: "The side walls are 3 ft. 7 in. ... in thickness."

- ^ Cochrane 1914, p. 6: "The walls of nave and choir are 28 ft. 9 in. in height and were finished by water tables formed of overlapping slabs, and had stepped parapets ..."

- ^ Halpin & Newman 2006, p. 249, line 20: "At the east end of the nave is a partly reconstructed rood screen and gallery ..."

- ^ Crawford 1921, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Wood-Martin 1889, p. 309: "In Sligo, as at Moyne, the cloisters are situated on the north side of the nave, the more usual position being on the south."

- ^ Halpin & Newman 2006, p. 249: "... arcade of pointed arches supported by well-carved pillars, of late 15th century date."

- ^ Halpin & Newman 2006, p. 249, line 32: "... on the north-east side of the church, the vaulted sacristy, vestry and chapter house are largely original 13th-century fabric."

- ^ Cochrane 1914, p. 7: "... light was provided by an oriel window supported on a projecting bracket."

- ^ Crawford 1921, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Crawford 1921, pp. 19–29.

- ^ McGurk 2004, p. 809–811.

- ^ Yeats 1914, p. 83.

- ^ Yeats 1914, p. 134.

- ^ "Oldest painting of Abbey goes on public display". independent. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

References edit

- Bell, Thomas (1829). An Essay on the Origin and Progress of Gothic Architecture, with Reference to the Ancient History and Present State of the Remains of such Architecture in Ireland. Dublin: William Frederick Wakeman. OCLC 1045213323.

- Cochrane, Robert (1914). The Ecclesiastical Remains of Sligo Abbey, co. Sligo. Dublin: His/Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 1049891361.

- Coleman, Ambrose (1902). The Ancient Dominican Foundations of Ireland; an Appendix to O'Heyn's "Epilogus Chronologicus". Dundalk: William Tempest.

- Crawford, Henry S. (1921). "The Carved Altar and Mural Monuments in Sligo Abbey". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 6th. 11 (1): 17–31. JSTOR 25514587.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I., eds. (1986). Handbook of British Chronology. Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks, No. 2 (3rd ed.). London: Offices of the Royal Historical Society. ISBN 0-86193-106-8.

- Halpin, Andrew; Newman, Conor (2006). Ireland: An Oxford Archeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280671-0.

- McGurk, J. J. N. (2004). "FitzGerald, Gerald Fitz James (c. 1533–1583)". In Matthew, Colin; Harrison, Brian (eds.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 809–811. ISBN 0-19-861369-5.

- O'Rorke, Terence (1890). The History of Sligo: Town and County. Vol. 1. Dublin: J. Duffy.

- Smith, B. (2004). "FitzGerald, Maurice (c. 1194–1257)". In Matthew, Colin; Harrison, Brian (eds.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 832–833. ISBN 0-19-861369-5.

- Taaffe, Rudolph (1958). "Taaffe of County Louth". Journal of County Louth Archaeological Society. 14 (2): 55–67. doi:10.2307/27728944. JSTOR 27728944.

- Yeats, William Butler (1914). Stories of Red Hanrahan - The Secret Rose - Rosa Alchemica. New York: The MacMillan Company.

- Webb, Alfred (1878a). "FitzGerald, Maurice, 2nd Baron Offaly". Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son. p. 181, left column.

- Webb, Alfred (1878b). "Taaffe, Theobald, Viscount Taaffe". Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son. p. 513–514.

- Wood-Martin, William Gregory (1882). The History of Sligo, County and Town: From the Earliest Times to the Close of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. Vol. 1. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co.

- Wood-Martin, William Gregory (1889). The History of Sligo, County and Town: From the Accession of James I to the Revolution of 1688. Vol. 2. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co.

- Wood-Martin, William Gregory (1892). The History of Sligo, County and Town: From the Close of the Revolution of 1688 to the Present Time. Vol. 3. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co.

External links edit

- http://monastic.ie/history/sligo-dominican-priory/

- http://heritageireland.ie/visit/places-to-visit/sligo-abbey/ – Official site at Heritage Ireland

- http://irishantiquities.bravehost.com/sligo/sligo/sligofriary.html – Sligo Friary on the Irish Antiquities website

- http://www.ecclesiasticalireland.org/sligo/index.htm – Sligo Abbey on the Ecclesiastical Ireland website

54°16′15″N 8°28′12″W / 54.270809°N 8.470091°W