Summary

Suffolk (/ˈsʌfək/ SUF-ək) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county town.

Suffolk | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Guide Our Endeavour" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 52°12′N 1°00′E / 52.200°N 1.000°E | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | East |

| Established | Ancient |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (British Summer Time) |

| Members of Parliament | List of MPs |

| Police | Suffolk Constabulary |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Lord Lieutenant | Clare FitzRoy, Countess of Euston |

| High Sheriff | Bridget McIntyre[1] (2020–21) |

| Area | 3,798 km2 (1,466 sq mi) |

| • Ranked | 8th of 48 |

| Population (2021) | 758,556 |

| • Ranked | 32nd of 48 |

| Density | 200/km2 (520/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | 97.2% White |

| Non-metropolitan county | |

| County council | Suffolk County Council |

| Executive | Conservative |

| Admin HQ | Ipswich |

| Area | 3,800 km2 (1,500 sq mi) |

| • Ranked | 4th of 21 |

| Population | 763,375 |

| • Ranked | 14th of 21 |

| Density | 201/km2 (520/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-SFK |

| ONS code | 42 |

| GSS code | E10000029 |

| ITL | UKH14 |

| Website | suffolk |

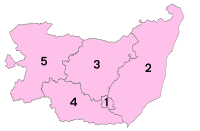

| Districts | |

Districts of Suffolk | |

| Districts | |

The county has an area of 3,798 km2 (1,466 sq mi) and a population of 758,556. After Ipswich (144,957) in the south, the largest towns are Lowestoft (73,800) in the north-east and Bury St Edmunds (40,664) in the west. Suffolk contains four local government districts, which are part of a two-tier non-metropolitan county also called Suffolk.

The Suffolk coastline is a complex habitat, formed by London clay and crag underlain by chalk and therefore susceptible to erosion. It contains several deep estuaries, including those of the rivers Byth, Deben, Orwell, Stour, and Alde/Ore; the latter is 25.5 km (15.8 mi) long and separated from the North Sea by Orford Ness, a large spit. Large parts of the coast are backed by heath and wetland habitats, such as Sandlings.[2] The north-east of the county contains part of the Broads, a network of rivers and lakes. Inland, the landscape is flat and gently undulating, and contains part of Thetford Forest on the Norfolk border and Dedham Vale on the Essex border.

It is also known for its extensive farming and has largely arable land. Newmarket is known for horse racing, and Felixstowe is one of the largest container ports in Europe.[3]

History edit

Administration edit

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Suffolk, and East Anglia generally, occurred on a large scale,[4] possibly following a period of depopulation by the previous inhabitants, the Romanised descendants of the Iceni.[5] By the fifth century, they had established control of the region. The Anglo-Saxon inhabitants later became the "north folk" and the "south folk", from which developed the names "Norfolk" and "Suffolk".[6]

Suffolk was divided into four separate Quarter Sessions divisions, which met at Beccles, Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and Woodbridge.[7] In 1860, the number of divisions was reduced to two, when the Beccles, Ipswich and Woodbridge divisions merged into an East Suffolk division, administered from Ipswich, and the old Bury St Edmunds division became the West Suffolk division.[8] Under the Local Government Act 1888, the two divisions were made the separate administrative counties of East Suffolk and West Suffolk;[9]

On 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, East Suffolk, West Suffolk, and Ipswich were merged to form the unified county of Suffolk. The county was divided into several local government districts: Babergh, Forest Heath, Ipswich, Mid Suffolk, St Edmundsbury, Suffolk Coastal, and Waveney. This act also transferred some land near Great Yarmouth to Norfolk. As introduced in Parliament, the Local Government Act would have transferred Newmarket and Haverhill to Cambridgeshire and Colchester from Essex; such changes were not included when the act was passed into law.[10]

In 2007 the Department for Communities and Local Government referred Ipswich Borough Council's bid to become a new unitary authority to the Boundary Committee.[11] Beginning in February 2008, the Boundary Committee again reviewed local government in the county, with two possible options emerging. One was that of splitting Suffolk into two unitary authorities – Ipswich and Felixstowe and Rural Suffolk; and the other, that of creating a single county-wide controlling authority – the "One Suffolk" option.[12] In February 2010, the then-Minister Rosie Winterton announced that no changes would be imposed on the structure of local government in the county as a result of the review, but that the government would be: "asking Suffolk councils and MPs to reach a consensus on what unitary solution they want through a countywide constitutional convention".[13] Following the May 2010 general election, all further moves towards any of the suggested unitary solutions ceased on the instructions of the incoming Cameron–Clegg coalition.[14] In 2018 it was determined that Forest Heath and St Edmundsbury would be merged to form a new West Suffolk district,[15] while Waveney and Suffolk Coastal would similarly form a new East Suffolk district.[16]

Archaeology edit

West Suffolk, like nearby East Cambridgeshire, is renowned for archaeological finds from the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Bronze Age artefacts have been found in the area between Mildenhall and West Row, in Eriswell and in Lakenheath.[17]

In the east of the county is Sutton Hoo, the site of one of England's most significant Anglo-Saxon archaeological finds, a ship burial containing a collection of treasures including a sword of state, helmet, gold and silver bowls, jewellery and a lyre.[18]

While carrying out surveys before installing a pipeline in 2014, archaeologists for Anglian Water discovered nine skeletons and four cremation pits, at Bardwell, Barnham, Pakenham and Rougham, all near Bury St Edmunds. Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman and medieval items were also unearthed, along with the nine skeletons believed to be of the late or Post-Roman Britain. Experts said the five-month project had recovered enough artefacts to fill half a shipping container, and that the discoveries had shed new light on their understanding of the development of small rural communities.[19]

In 2019 an excavation of a 4th-century Roman burial in Great Whelnetham uncovered unusual burial practices. Of 52 skeletons found, a large number had been decapitated, which archaeologists claimed gave new insight into Roman traditions. The burial ground includes the remains of men, women and children who likely lived in a nearby settlement. The fact that up to 40% of the bodies were decapitated represents "quite a rare find".[20]

A survey in 2020 named Suffolk the third best place in the UK for aspiring archaeologists, and showed that the area was especially rich in finds from the Roman period, with over 1500 objects found in the preceding year.[21]

In July 2020, metal detectorist Luke Mahoney found 1,061 silver hammered coins, estimated to be worth £100,000, in Ipswich. The coins dated back to the 15th–17th century, according to experts.[22]

In September 2020, archaeologists announced the discovery of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery with seventeen cremations and 191 burials dating back to the 7th century in Oulton, near Lowestoft. The graves contained the remains of men, women and children, as well as artefacts including small iron knives and silver pennies, wrist clasps, strings of amber and glass beads. According to Andrew Peachey, who carried out the excavations, the skeletons had mostly vanished because of the highly acidic soil. They, fortunately, were preserved as brittle shapes and "sand silhouettes" in the sand.[23][24]

Suffolk Pink edit

Villages and towns in Suffolk are renowned for historic, pink-washed halls and cottages, which has become known far and wide as "Suffolk Pink". Decorative paint colours found in the county can range from a pale shell shade, to a deep blush brick colour.[25]

According to research, Suffolk Pink dates back to the 14th century, when these shades were developed by local dyers by adding natural substances to a traditional limewash mix. Additives used in this process include pig or ox blood with buttermilk, elderberries and sloe juice.

Locals and historians often state that a true Suffolk Pink should be a "deep dusky terracotta shade",[26] rather than the more popular pastel hue of modern times. This has caused controversy in the past when home and business-owners alike have been reprimanded for using colours deemed incorrect, with some being forced to repaint to an acceptable shade. In 2013, famous chef Marco Pierre White had his 15th-century hotel, The Angel, in Lavenham, decorated a shade of pink that was not traditional Suffolk Pink. He was required by local authorities to repaint.[27][28]

In another example of Suffolk taking its colours seriously, a homeowner in Lavenham was obligated to paint their Grade I listed cottage Suffolk Pink, to make it match a neighbouring property. The local council said it wanted all of the cottages on that particular part of the road to be the same colour, because they were a single building historically (300 years earlier).[29]

The historic Suffolk Pink colour has also inspired the name of a British apple.[30]

Geography edit

Suffolk is also home to nature reserves, such as the RSPB site at Minsmere, and Trimley Marshes, a wetland under the protection of Suffolk Wildlife Trust. The clay plateau inland, deeply intercut by rivers, is often referred to as 'High Suffolk'.[31]

The west of the county lies on more resistant Cretaceous chalk. This chalk is responsible for a sweeping tract of largely downland landscapes that stretches from Dorset in the south west to Dover in the south east and north through East Anglia to the Yorkshire Wolds. The chalk is less easily eroded so forms the only significant hills in the county. The highest point in the county is Great Wood Hill, with an elevation of 128 metres (420 ft).[32]

Demography edit

According to estimates by the Office for National Statistics, the population of Suffolk in 2014 was 738,512, split almost evenly between males and females. Roughly 22% of the population was aged 65 or older, and 90.84% were White British.[34]

Historically, the county's population has mostly been employed as agricultural workers. An 1835 survey showed Suffolk to have 4,526 occupiers of land employing labourers, 1,121 occupiers not employing labourers, 33,040 labourers employed in agriculture, 676 employed in manufacture, 18,167 employed in retail trade or handicraft, 2,228 'capitalists, bankers etc.', 5,336 labourers (non-agricultural), 4,940 other males aged over 20, 2,032 male servants and 11,483 female servants.[35]

Most English counties have nicknames for people from that county, such as a Tyke from Yorkshire and a Yellowbelly from Lincolnshire. A traditional nickname for people from Suffolk is "Suffolk Fair-Maids", referring to the supposed beauty of its female inhabitants in the Middle Ages.[36]

Another is "Silly Suffolk", often assumed to be derived from the Old English word sælig in the meaning "blessed", referring to the long history of Christianity in the county.[37] However, use of the term "Silly Suffolk" can actually be dated to no earlier than 1819, and its alleged medieval origins have been shown to be mythical.[38]

| Rank | Town | Population (2011) |

Borough/District council |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ipswich | 133,384 | Ipswich Borough Council |

| 2 | Lowestoft | 71,000 | East Suffolk Council |

| 3 | Bury St Edmunds | 42,000 | West Suffolk Council |

| 4 | Haverhill | 27,041 | West Suffolk Council |

| 5 | Felixstowe | 23,689 | East Suffolk Council |

| 6 | Newmarket | 20,384 | West Suffolk Council |

Economy edit

The majority of agriculture in Suffolk is either agronomy or mixed farming. Farm sizes vary from anything around 80 acres (32 hectares) to over 8,000. Soil types vary from heavy clays to light sands. Crops grown include winter wheat, barley, sugar beet, oilseed rape, winter and spring beans and linseed, although smaller areas of rye and oats can be found growing in areas with lighter soils along with a variety of vegetables.[citation needed]

The continuing importance of agriculture in the county is reflected in the Suffolk Show, which is held annually in May at Ipswich. Although latterly somewhat changed in nature, this remains primarily an agricultural show.[39]

Companies based in Suffolk include Greene King and Branston Pickle in Bury St Edmunds. Birds Eye has its largest UK factory in Lowestoft, where all its meat products and frozen vegetables are processed. Huntley & Palmers biscuit company has a base in Sudbury. The UK horse racing industry is based in Newmarket. There are two United States Air Force bases in the west of the county close to the A11. Sizewell B nuclear power station is at Sizewell on the coast near Leiston. Bernard Matthews Farms have some processing units in the county, specifically Holton. Southwold is the home of Adnams Brewery. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest container port in the United Kingdom. Other ports are at Lowestoft and Ipswich, run by Associated British Ports. BT Group plc has its main research and development facility at Martlesham Heath.

Below is a chart of regional gross value added of Suffolk at basic prices published by Office for National Statistics with figures in millions of British Pounds Sterling.

| Year | Regional gross value added[fn 1] | Agriculture[fn 2] | Industry[fn 3] | Services[fn 4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 7,113 | 391 | 2,449 | 4,273 |

| 2000 | 8,096 | 259 | 2,589 | 5,248 |

| 2003 | 9,456 | 270 | 2,602 | 6,583 |

| Source[40] | ||||

Education edit

Primary, secondary and further education edit

Suffolk has a comprehensive education system with fourteen independent schools. Unusually for the UK, some of Suffolk had a 3-tier school system in place with primary schools (ages 5–9), middle schools (ages 9–13) and upper schools (ages 13–16). However, a 2006 Suffolk County Council study concluded that Suffolk should move to the two-tier school system used in the majority of the UK.[41] For the purpose of conversion to two-tier, the three-tier system was divided into four geographical area groupings and corresponding phases. The first phase was the conversion of schools in Lowestoft and Haverhill in 2011, followed by schools in north and west Suffolk in 2012. The remainder of the changeovers to two-tier took place from 2013, for those schools that stayed within local government control, and did not become Academies and/or free schools. The majority of schools thus now (2019) operate the more common primary to high school (11–16).

Many of the county's upper schools have a sixth form and most further education colleges in the county offer A-level courses. In terms of school population, Suffolk's individual schools are large with the Ipswich district with the largest school population and Forest Heath the smallest, with just two schools. In 2013, a letter said that "...nearly a fifth of the schools inspected were judged inadequate. This is unacceptable and now means that Suffolk has a higher proportion of pupils educated in inadequate schools than both the regional and national averages."[42]

The Royal Hospital School near Ipswich is the largest independent boarding school in Suffolk. Other boarding schools within Suffolk include Barnardiston Hall Preparatory School, Culford School, Finborough School, Framlingham College, Ipswich High School, Ipswich School, Orwell Park School, Saint Felix School and Woodbridge School.

The Castle Partnership Academy Trust in Haverhill is the county's only All-through Academy Chain. Comprising Castle Manor Academy and Place Farm Primary Academy, the Academy Trust supports all-through education and provides opportunities for young people aged 3 to 18.

Sixth form colleges in the county include Lowestoft Sixth Form College and One in Ipswich. Suffolk is home to four further education colleges: Lowestoft College, Easton & Otley College, Suffolk New College (Ipswich) and West Suffolk College (Bury St Edmunds).

Tertiary education edit

The county has one university, with branches spread across different towns. University of Suffolk was, prior to August 2016, known as University Campus Suffolk. Up until it became independent it was a collaboration between the University of Essex and the University of East Anglia which sponsored its formation and validated its degrees.[43][44] UOS accepted its first students in September 2007. Until then Suffolk was one of only four counties in England which did not have a university campus.[43] The University of Suffolk was granted Taught Degree Awarding Powers by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education in November 2015, and in May 2016 it was awarded University status by the Privy Council and renamed The University of Suffolk on 1 August 2016.[45][46]

The university operates at five sites, with its central hub in Ipswich. Others include Lowestoft, Bury St. Edmunds, and Great Yarmouth in Norfolk.[47] The university operates two academic faculties and in 2019/20 had 9,565 students. Some 30% of the student body are classed as mature students and 68% of university students are female.[48]

Culture edit

Arts edit

Founded in 1948 by Benjamin Britten, the annual Aldeburgh Festival is one of the UK's major classical music festivals. Originating in Aldeburgh, it has been held at the nearby Snape Maltings since 1967.[49] Since 2006, Henham Park, has been home to the annual Latitude Festival. This mainly open-air festival, which has grown considerably in size and scope, includes popular music, comedy, poetry and literary events. The FolkEast festival is held at Glemham Hall in August[50] and attracts international acoustic, folk and roots musicians whilst also championing local businesses, heritage and crafts. In 2015 it was also home to the first instrumental festival of musical instruments and makers.[51] More recently, LeeStock Music Festival has been held in Sudbury.[52] A celebration of the county, "Suffolk Day", was instigated in 2017.[53]

Dialect edit

The Suffolk dialect is very distinctive. Epenthesis and yod-dropping is common, along with non-conjugation of verbs.[54]

Sport edit

Football edit

The county's sole professional football club is Ipswich Town. Formed in 1878, the club were Football League champions in 1961–62, FA Cup winners in 1977–78 and UEFA Cup winners in 1980–81;[55] as of the 2023–24 season, Ipswich Town play in the Championship, the second tier of English football. The club has as part of its crest the Suffolk Punch, a now endangered breed of draught horse native to the county. The next highest ranked teams in Suffolk are AFC Sudbury, Leiston and Needham Market, who all participate in the Southern League Premier Division Central, the seventh tier of English football.

Horse racing edit

The town of Newmarket is the headquarters of British horseracing – home to the largest cluster of training yards in the country and many key horse racing organisations including the National Stud,[56] and Newmarket Racecourse. Tattersalls bloodstock auctioneers and the National Horseracing Museum are also in the town.[57][58] Point to point racing takes place at Higham and Ampton.[59]

Speedway edit

Speedway racing has been staged in Suffolk since at least the 1950s, following the construction of the Foxhall Stadium, just outside Ipswich, home of the Ipswich Witches. The Witches are currently members of the Premier League, the UK's first division.[60] National League team Mildenhall Fen Tigers are also from Suffolk.[61]

Cricket edit

Suffolk County Cricket Club compete in the Eastern Division of the Minor Counties Championship.[62] The club has won the championship three times outright and has shared the title one other time as well as winning the MCCA Knockout Trophy once.[63] Home games are played in Bury St Edmunds, Copdock, Exning, Framlingham, Ipswich and Mildenhall.[64]

Suffolk in popular culture edit

Novels set in Suffolk include parts of David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, The Fourth Protocol, by Frederick Forsyth, Unnatural Causes by P.D. James, Dodie Smith's The Hundred and One Dalmatians, The Rings of Saturn by W. G. Sebald,[65] and among Arthur Ransome's children's books, We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea, Coot Club and Secret Water take place in part in the county. Roald Dahl's short story "The Mildenhall Treasure" is set in Mildenhall.[66]

A TV series about a British antiques dealer, Lovejoy, was filmed in various locations in Suffolk.[67] The reality TV series Space Cadets was filmed in Rendlesham Forest, although the producers fooled participants into believing that they were in Russia.[68] Several towns and villages in the county have been used for location filming of other television programmes and cinema films. These include the BBC Four TV series Detectorists,[69] an episode of Kavanagh QC, and the films Iris and Drowning by Numbers. During the period 2017–2018, a total of £3.8million was spent by film crews in Suffolk.[70]

The Rendlesham Forest Incident is one of the most famous UFO events in England and is sometimes referred to as "Britain's Roswell".[71]

The song "Castle on the Hill" by Ed Sheeran was referred to by him as "a love letter to Suffolk", with lyrical references to his hometown of Framlingham and Framlingham Castle.[72][73]

Knype Hill is the fictional name for Southwold in George Orwell's 1935 novel A Clergyman's Daughter, while the character of Dorothy Hare is modelled on Brenda Salkeld, the gym mistress at St Felix School in the early 1930s.[74]

Richard Curtis and Danny Boyle's 2019 romantic comedy Yesterday was filmed throughout Suffolk, using Halesworth, Dunwich, Shingle Street and Latitude Festival as locations.[75] The television series of Anthony Horowitz's Magpie Murders was filmed extensively in Suffolk during 2021.

The 2021 film The Dig, based on the excavation of Sutton Hoo in the 1930s and starring Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan was mostly shot on location.

The 2022 series The Witchfinder is a BBC Two sitcom based on the journey of Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder general, and a suspected witch through East Anglia and many Suffolk towns including Stowmarket and Framlingham during the witch trials of the English Civil War.

Media edit

Television edit

The county is covered by BBC East and ITV Anglia which broadcast from Norwich. Television signals are received from the Tacolneston TV transmitter in the north of Suffolk,[76] Sudbury TV transmitter in the central and south of Suffolk, [77] and the Sandy Heath TV transmitter in Bedfordshire that broadcast in the west of Suffolk.[78]

Radio edit

BBC Local Radio for the county is served by BBC Radio Suffolk which broadcast from its studios in Ipswich. County-wide commercial radio stations are Heart East, Greatest Hits Radio East and Nation Radio Suffolk. Community based stations such as ICR FM (serving Ipswich) and RWSfm 103.3 (covering Bury St Edmunds).

Newspapers edit

The county is served by these local newspapers:

Notable people edit

In the arts, Suffolk is noted for having been home to two of England's best regarded painters, Thomas Gainsborough[79] and John Constable – the Stour Valley area is branded as "Constable Country"[80] – and one of its most noted composers, Benjamin Britten.[81] Other artistic figures connected with Suffolk include: Sir Alfred Munnings, John Nash, sculptor Dame Elizabeth Frink, Cedric Morris who ran the East Anglian School, Philip Wilson Steer, and the cartoonist Carl Giles (a bronze statue of his character "Grandma" is located in Ipswich town centre); the poets George Crabbe[82] and Robert Bloomfield were both born in Suffolk;[83] farmer and writer Adrian Bell, writer and literary editor Ronald Blythe, V. S. Pritchett, the authors Ralph Hammond Innes and Ruth Rendell all lived in the county.

The writer M. M. Kaye spent her last years in Suffolk and died in Lavenham. Actors Ralph Fiennes[84] and Bob Hoskins, actress and singer Kerry Ellis, musician and record producer Brian Eno,[85] multi-award winning singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran and sopranos Laura Wright and Christina Johnston[86] are all connected with the county. Glam rock band and three time Brit Award winners the Darkness hail from Lowestoft.

Hip hop DJ Tim Westwood is originally from Suffolk and the influential DJ and radio presenter John Peel made the county his home.[87] Contemporary painter Maggi Hambling, was born and resides in Suffolk. Norah Lofts, author of best-selling historical novels, lived for decades in Bury St. Edmunds. Sir Peter Hall the founder of the Royal Shakespeare Company was born in Bury St. Edmunds, and Sir Trevor Nunn the theatre director was born in Ipswich. The actor Sir John Mills spent periods of his youth in the county. The designer David Hicks lived for a number of years in Suffolk. Model Claudia Schiffer and her husband, the film director Matthew Vaughn, have owned a house in Suffolk since 2002.

Suffolk's contributions to sport include Formula One magnate Bernie Ecclestone and former England footballers Terry Butcher, Kieron Dyer and Matthew Upson. Due to Newmarket being the centre of British horse racing many jockeys have settled in the county, including Lester Piggott and Frankie Dettori. MMA fighter Arnold Allen was born in Suffolk. Fabio Wardley English heavyweight champion is also from Suffolk.

Significant ecclesiastical figures from Suffolk include Simon Sudbury, a former archbishop of Canterbury;[88] former Lord High Chancellor Cardinal Thomas Wolsey hailed from Ipswich;[89] and author, poet and Benedictine monk John Lydgate.[90] Richard Hakluyt the great recorder of exploration and voyages was a clergyman in Wetheringsett. Edward FitzGerald, the first translator of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, was born in Bredfield. The abolitionists Thomas Clarkson and Richard Dykes Alexander both lived near Ipswich. The agriculturist Arthur Young had a long-standing association with the county.

Other significant persons from Suffolk include the great landscape designer Humphry Repton, suffragette Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett;[91] the captain of HMS Beagle, Robert FitzRoy;[92] Witch-finder General Matthew Hopkins;[93] educationist Hugh Catchpole;[94][95] and Britain's first female physician and mayor, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson.[96] The tuberculosis treatment pioneer Jane Walker ran the East Anglian Sanatorium above the banks of the River Stour, and charity leader Sue Ryder settled in Suffolk and based her charity in Cavendish.

The popular Victorian novelist Henry Seton Merriman lived and died in the village of Melton. Between 1932 and 1939 George Orwell lived at his parents' home in the coastal town of Southwold, where a mural of the author now dominates the entrance to Southwold Pier.[97] He is said to have chosen his pen name from Suffolk's River Orwell. Arthur Ransome lived alongside the river during the 1930s, sailing his boats from Pin Mill and along the Shotley Peninsula. The county was also home to wild swimmer and environmentalist Roger Deakin.

Edmund of East Anglia edit

King of East Anglia and Christian martyr St Edmund, after whom the town of Bury St Edmunds is named, was killed by invading Danes in the year 869. St Edmund was the patron saint of England until he was replaced by St George in the 13th century. 2006 saw the failure of a campaign to have St Edmund named the patron saint of England. In 2007 he was named the patron saint of Suffolk, with St Edmund's Day falling on 20 November. His flag is flown in Suffolk on that day.

Gallery edit

See also edit

Notes edit

References edit

- ^ "No. 62943". The London Gazette. 13 March 2020. p. 5161.

- ^ "Features and Habitats". coastandheaths.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Top 50 Container Ports in Europe". World Shipping Council. Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Toby F. Martin, The Cruciform Brooch and Anglo-Saxon England, Boydell and Brewer Press (2015), pp. 174–178

- ^ Dark, Ken R. "Large-scale population movements into and from Britain south of Hadrian's Wall in the fourth to sixth centuries AD" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "English Place Names". englishplaceneames.co.uk. James Rye. Archived from the original on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Reports of cases argued and determined in the Queen's Bench Practice Court. Bail Court Great Britain. 1848. p. 628.

- ^ "Suffolk March Sessions". Ipswich Journal. 17 March 1860. p. 6. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ "Local Government Act, 1888" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "UK Government Web Archive". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- ^ "Suffolk structural review". The Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ "Unitary authorities-Exeter and Norwich get green light". Department for Communities and Local Government. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "Pickles stops unitary councils in Exeter, Norwich and Suffolk". Department for Communities and Local Government. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (24 May 2018). "The West Suffolk (Local Government Changes) Order 2018". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (24 May 2018). "The East Suffolk (Local Government Changes) Order 2018". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Hall, David (1994). Fenland survey : an essay in landscape and persistence / David Hall and John Coles. English Heritage. pp. 81–88. ISBN 1850744777.

- ^ "Sutton Hoo History". The National Trust. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ "Roman skeletons discovered by Anglian Water in Barnham, Bardwell, Pakenham and Rougham". East Anglian Daily Times. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Decapitated bodies found in Roman cemetery in Great Whelnetham". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Suffolk 'third best place in UK' to find archaeological treasures, survey shows". East Anglian Daily Times. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Metal detectorist guards £100k hoard of silver for two sleepless nights over 'nighthawk' fears". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Oulton burial site: Sutton Hoo-era Anglo-Saxon cemetery discovered". BBC News. 16 September 2020. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Fox, Alex. "This Anglo-Saxon Cemetery Is Filled With Corpses' Ghostly Silhouettes". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "History of Suffolk county's architecture". Britain Magazine. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Partner, Claire (13 January 2018). "Why is pink the traditional colour to paint houses in Suffolk?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Marco Pierre White repaints Angel Hotel Suffolk pink". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ Gaw, Matt. "Lavenham: Village not tickled pink by Marco Pierre White's paint choice". East Anglian Daily Times. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "The history behind Suffolk Pink houses". Fenn Wright. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "The origin of the Suffolk Pink apple variety". Real English Fruit. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Suffolk's forgotten beauty". Suffolk Magazine. 19 September 2016. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Bathurst, David (2012). Walking the county high points of England. Summersdale. pp. 21–26. ISBN 9781849532396.

- ^ "Plant & fungi species: Wild plants". Plantlife.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ "Area Profile Suffolk Observatory". suffolkobservatory.info. GeoWise. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ 'The British Almanac' – 1835

- ^ Nall, John Greaves (2006). Nall's Glossary of East Anglian Dialect. Larks Press. ISBN 9781904006343.

- ^ Torlesse, Charles Martin (1877). Some Account of Stoke by Nayland, Suffolk. Harrison.

- ^ Briggs, Keith (2022). "Silly Suffolk". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. 45 (2): 295.

- ^ "The Suffolk Show". suffolkshow.co.uk. Suffolk Show 2015. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] UK Government Web Archive" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2007.

- ^ "Suffolk Free Press". Sudburytoday.co.uk. Retrieved 6 June 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Letter to local authority DCS following focused school inspections" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ a b University Campus Suffolk Archived 26 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, University of Essex. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ University Campus Suffolk guide Archived 27 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Telegraph, 21 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "University Campus Suffolk gains independence". BBC News. 17 May 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "University Campus Suffolk gains approval to become the University of Suffolk". ucs.ac.uk. 4 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ University Campus Suffolk Archived 7 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, University of East Anglia. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "University of Suffolk". university.which.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Aldeburgh Festival History". aldeburgh.co.uk. Aldeburgh Music. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Festivals guide 2014 listings: folk and world music". The Guardian. 31 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ "Instrumental at Folk East". folkeast.co.uk. FolkEast Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "LeeStock Music Festival". leestock.org. Leestock Musical Festival Ltd. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Why we should celebrate our county with Suffolk Day". East Anglian Daily Times. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Claxton, A. O. D. (1954). The Suffolk Dialect of the Twentieth Century (First ed.). Ipswich, Suffolk: The Boydell Press Ltd. ISBN 0-85115-026-8.

- ^ "Club honours". Ipswich Town F.C. Archived from the original on 13 December 2005. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ^ "Suffolk Tourism". suffolktouristguide.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ^ "Tattersalls". tattersalls.com. Tattersalls Ltd. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "National Horseracing Museum". National Horseracing Museum. Retrieved 21 October 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Courses". pointingea.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ^ "Ipswich Speedway Official Website". ipswichwitches.co. Ipswich Speedway. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Mildenhall Fen Tigers". mildenhallfentigers.co. Mildenhall Speedway. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Minor Counties Cricket Association". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 23 August 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^ "Minor Counties Roll of Honour". ecb.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^ "Minor County Grounds". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- ^ "The Rings of Saturn". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ "Roald Dahl and the Mildenhall Treasure". British Museum. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Memories of Lovejoy, the man who put East Anglia on the map". Sudbury Mercury. February 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Space Cadets". ukgameshows.com. UK Game Shows. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Season 1, DVD extra 'Behind-the-Scenes'

- ^ "David Copperfield film shoot in Bury St Edmunds generated £82,500 for town's economy". Bury Free Press. 1 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ "UFOFiles Rendlesham Forest". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Castle on the Hill: Ed Sheeran's love letter to Suffolk, Ed Sheeran co-host..., Scott Mills – BBC Radio 1". BBC. 6 January 2017. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "Ed Sheeran". Contactmusic.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "George Orwell's Southwold home gets fresh plaque". BBC News. 21 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Wilkin, Chris (26 April 2018). "Danny Boyle's new Beatles musical was being filmed in north Essex". Daily Gazette. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Tacolneston (Norfolk, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Sudbury (Suffolk, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Sandy Heath (Central Bedfordshire, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Biography". Gainsborough's House. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Constable Country walk". The National Trust. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Interviews: Benjamin Britten 1913 – 1976". BBC Four. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "George Crabbe | English poet". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Cousin, John W. "A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ^ "Ralph Fiennes | Biography & Credits". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Brian Eno on British musician and producer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Hirst, Andrew (1 May 2014). "Framlingham/Prague: Former Suffolk schoolgirl Christina Johnston described as an "angel" as she sings for European leaders". East Anglian Daily Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Lusher, Adam (21 October 2006). "John Peel leaves his wife £1.5m, oh, and 25,000 records". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "Simon Of Sudbury: English archbishop". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Thomas, Cardinal Wolsey | English cardinal and statesman". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "John Lydgate: English writer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Russell, Steve. "Women's Week: Millicent Fawcett – a Suffolk campaigner who helped change history for UK women". East Anglian Daily Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Trust, HMS Beagle. "ROBERT FITZROY BORN IN SUFFOLK · The HMS BEAGLE PROJECT". hmsbeagleproject.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Matthew Hopkins: English witch-hunter". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Hugh Catchpole: An institution unto himself". Dawn. Pakistan. 20 September 2008. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ "Hugh Catchpole: Founder Principal". cch.edu.pk. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Havard, Lucy. "Women's Week: Suffolk's Elizabeth Garrett Anderson changed the course of women in medicine". East Anglian Daily Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "George Orwell's Southwold home gets fresh plaque". BBC Suffolk. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2020.