Summary

The 1997 United Kingdom general election was held on Thursday, 1 May 1997. The governing Conservative Party led by Prime Minister John Major was defeated in a landslide by the Labour Party led by Tony Blair, achieving a 179-seat majority.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 659 seats to the House of Commons 330 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 43,846,152[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 71.3% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

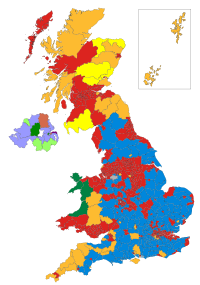

Colours denote the winning party, as shown in the main table of results. * Indicates boundary change, so this is a nominal figure. † Notional 1992 results on new boundaries. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

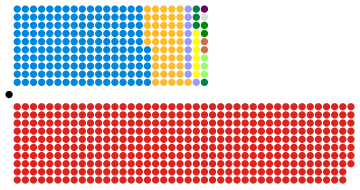

Composition of the House of Commons after the election | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The political backdrop of campaigning focused on public opinion towards a change in government. Blair, as Labour Leader, focused on transforming his party through a more centrist policy platform, titled 'New Labour', with promises of devolution referendums for Scotland and Wales, fiscal responsibility, and a decision to nominate more female politicians for election through the use of all-women shortlists from which to choose candidates. Major sought to rebuild public trust in the Conservatives following a series of scandals, including the events of Black Wednesday in 1992,[3] through campaigning on the strength of the economic recovery following the early 1990s recession, but faced divisions within the party over the UK's membership of the European Union.[4]

Opinion polls during campaigning showed strong support for Labour due to Blair's personal popularity,[5][6] and Blair won a personal public endorsement from The Sun newspaper two months before the vote.[7] The final result of the election on 2 May 1997 revealed that Labour had won a landslide majority, making a net gain of 146 seats and winning 43.2% of the vote. 150 Members of Parliament, including 133 Conservatives, lost their seats. The Conservatives, meanwhile, suffered defeat with a net loss of 178 seats, winning 30.7% of the vote. The Liberal Democrats, under the leadership of Paddy Ashdown, made a net gain of 28 seats, winning 16.8% of the vote.

The election ended 18 years of Conservative government, its result the party's worst defeat since 1906; it was left devoid of any MPs outside England, with only 17 MPs north of the Midlands, and with less than 20% of MPs in London.[8] Immediately following the election Major resigned both as Prime Minister and as party leader. Labour's victory, the largest achieved in its history and by any political party in British politics since the Second World War, brought about the party's first of three consecutive terms in power (lasting a total of 13 years), with Blair as the newly appointed Prime Minister. The Liberal Democrats' success in the election, in part due to anti-Conservative tactical voting,[9] strengthened both Ashdown's leadership and the party's position as a strong third party, having won the highest number of seats by any third party since 1929.

Although the Conservatives lost many ministers such as Michael Portillo, Tony Newton, Malcolm Rifkind, Ian Lang and William Waldegrave and controversial MPs such as Neil Hamilton and Jonathan Aitken,[10] some of the Conservative newcomers in this election were future Prime Minister Theresa May, future Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, future Leader of the House Andrew Lansley, as well as future Speaker John Bercow. Meanwhile, Labour newcomers included future Cabinet and Shadow Cabinet members Hazel Blears, Ben Bradshaw, Yvette Cooper, Caroline Flint, Barry Gardiner, Alan Johnson, Ruth Kelly, John McDonnell, Stephen Twigg and Rosie Winterton, as well as future Scottish Labour Leader Jim Murphy and future Speaker Lindsay Hoyle. The election of 120 women, including 101 to the Labour benches, came to be seen as a watershed moment in female political representation in the UK.[11]

Overview edit

The British economy had been in recession at the time of the 1992 election, which the Conservatives had won, and although the recession had ended within a year, events such as Black Wednesday had tarnished the Conservative government's reputation for economic management. Labour had elected John Smith as its party leader in 1992, but his death from a heart attack in 1994 paved the way for Tony Blair to become Labour leader.

Blair brought the party closer to the political centre and abolished the party's Clause IV in their constitution, which had committed them to mass nationalisation of industry. Labour also reversed its policy on unilateral nuclear disarmament and the events of Black Wednesday allowed Labour to promise better economic management under the Chancellorship of Gordon Brown. Its manifesto, New Labour, New Life for Britain was released in 1996 and outlined five key pledges:

- Class sizes to be cut to 30 or under for 5-, 6- and 7-year-olds by using money from the assisted places scheme.

- Fast track punishment for persistent young offenders, by halving the time from arrest to sentencing.

- Cut NHS waiting lists by treating an extra 100,000 patients as a first step by releasing £100 million saved from NHS red tape.

- Get 250,000 under-25-year-olds off benefit and into work by using money from a windfall levy on the privatised utilities.

- No rise in income tax rates, cut VAT on heating to 5%, and keeping inflation and interest rates as low as possible.

Disputes within the Conservative government over European Union issues, and a variety of "sleaze" allegations, had severely affected the government's popularity. Despite the economic recovery and fall in unemployment in the four years leading up to the election, the rise in Conservative support was only marginal, with all of the major opinion polls having shown Labour in a comfortable lead since late 1992.[12]

Following the 1992 general election, the Conservatives remained in government with 336 of the 651 House of Commons seats. Through a series of defections and by-election defeats, the government gradually lost its absolute majority in the House of Commons. By 1997, the Conservatives held only 324 House of Commons seats (and had not won a by-election since Richmond in 1989).

Timing edit

The previous Parliament first sat on 29 April 1992. The Parliament Act 1911 required at the time for each Parliament to be dissolved before the fifth anniversary of its first sitting; therefore, the latest date the dissolution and the summoning of the next parliament could have been held on was 28 April 1997.

The 1985 amendment of the Representation of the People Act 1983 required that the election must take place on the eleventh working day after the deadline for nomination papers, which in turn must be no more than six working days after the next parliament was summoned.

Therefore, the latest date the election could have been held on was 22 May 1997 (which happened to be a Thursday). British elections (and referendums) have been held on Thursdays by convention since the 1930s, but can be held on other working days.

Campaign edit

Prime Minister John Major called the election on Monday 17 March 1997, ensuring the formal campaign would be unusually long, at six weeks (Parliament was dissolved on 8 April).[13] The election was scheduled for 1 May, to coincide with the local elections on the same day. This set a precedent, as the three subsequent general elections were also held alongside the May local elections.

The Conservatives argued that a long campaign would expose Labour and allow the Conservative message to be heard. However, Major was accused of arranging an early dissolution to protect Neil Hamilton from a pending parliamentary report into his conduct: a report that Major had earlier guaranteed would be published before the election.[14]

In March 1997, soon after the election was called, Asda introduced a range of election-themed beers, these being "Major's Mild", "Tony's Tipple" and "Ashdown's Ale".[15]

Conservative campaign edit

Major hoped that a long campaign would expose Labour's "hollowness" and the Conservative campaign emphasised stability, as did its manifesto title 'You can only be sure with the Conservatives'.[16] However, the campaign was beset by deep-set problems, such as the rise of James Goldsmith's Referendum Party which advocated a referendum on continued membership of the European Union. The party threatened to take away many right-leaning voters from the Conservatives. Furthermore, about 200 candidates broke with official Conservative policy to oppose British membership of the single European currency.[17] Major fought back, saying: "Whether you agree with me or disagree with me; like me or loathe me, don't bind my hands when I am negotiating on behalf of the British nation." The moment is remembered as one of the defining, and most surreal, moments of the election.[18][16]

Meanwhile, there was also division amongst the Conservative cabinet, with Chancellor Kenneth Clarke describing the views of Home Secretary Michael Howard on Europe as "paranoid and xenophobic nonsense". The Conservatives also struggled to come up with a definitive theme to attack Labour, with some strategists arguing for an approach which castigated Labour for "stealing Tory clothes" (copying their positions), with others making the case for a more confrontational approach, stating that "New Labour" was just a façade for "old Labour".

The New Labour, New Danger poster, which depicted Tony Blair with demon eyes, was an example of the latter strategy. Major veered between the two approaches, which left Conservative Central Office staff frustrated. As Andrew Cooper explained: "We repeatedly tried and failed to get him to understand that you couldn't say that they were dangerous and copying you at the same time."[19] In any case, the campaign failed to gain much traction, and the Conservatives went down to a landslide defeat at the polls.

Labour campaign edit

Labour ran a slick campaign that emphasised the splits within the Conservative government and argued that the country needed a more centrist administration. It thus successfully picked up dissatisfied Conservative voters, particularly moderate and suburban ones. Tony Blair, who was personally highly popular, was very much the centrepiece of the campaign and proved a highly effective campaigner.

The Labour campaign was reminiscent of those of Bill Clinton for the US presidency in 1992 and 1996, focusing on centrist themes as well as adopting policies more commonly associated with the right, such as cracking down on crime and fiscal responsibility. The influence of political "spin" came into great effect for Labour at this point, as media centric figures such as Alastair Campbell and Peter Mandelson provided a clear cut campaign, and establishing a relatively new political brand "New Labour" with enviable success. In this election Labour adopted the theme Things Can Only Get Better in their campaign and advertising.[20][21]

Liberal Democrat campaign edit

The Liberal Democrats had suffered a disappointing performance in 1992, but they were very much strengthened in 1997 due in part to potential tactical voting between Labour and Lib Dem supporters in Conservative marginal constituencies, particularly in the south of England – which explains why while given their share of the vote decreased, their number of seats nearly doubled.[9] The Lib Dems promised to increase education funding paid for by a 1p increase in income tax.

Endorsements edit

- In a sign of the change of direction which 'New Labour' represented, they were endorsed by The Sun (with a famous front page "The Sun Backs Blair"),[7] as well as the more left-leaning newspapers the Daily Mirror, The Independent and The Guardian.[22]

- The Conservatives were endorsed by the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, The Daily Telegraph and The Times.

Opinion polling edit

Notional 1992 results edit

The election was fought under new boundaries, with a net increase of eight seats compared to the 1992 election (651 to 659). Changes listed here are from the notional 1992 result, had it been fought on the boundaries established in 1997. These notional results were calculated by Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher and were used by all media organisations at the time.

| Party | Seats | Gains | Losses | Net gain/loss | Seats % | Votes % | Votes | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 273 | 17 | 15 | +2 | 41.6 | 34.4 | 11,560,484 | ||

| Conservative | 343 | 28 | 21 | +7 | 52.1 | 41.9 | 14,093,007 | ||

| Liberal Democrats | 18 | 0 | 2 | −2 | 2.7 | 17.8 | 5,999,384 | ||

| Other parties | 25 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 3.6 | 5.9 | |||

Results edit

Labour won a landslide victory with its largest parliamentary majority (179) to date. On the BBC's election night programme Professor Anthony King described the result of the exit poll, which accurately predicted a Labour landslide, as being akin to "an asteroid hitting the planet and destroying practically all life on Earth". After years of trying, Labour had convinced the electorate that they would usher in a new age of prosperity—their policies, organisation and tone of optimism slotting perfectly into place.

Labour's victory was largely credited to the charisma of Tony Blair,[23] as well as a Labour public relations machine managed by Alastair Campbell and Peter Mandelson. Between the 1992 election and the 1997 election there had also been major steps to "modernise" the party, including scrapping Clause IV that had committed the party to extending public ownership of industry. Labour had suddenly seized the middle ground of the political spectrum, attracting voters much further to the right than their traditional working class or left wing support. In the early hours of 2 May 1997 a party was held at the Royal Festival Hall, in which Blair stated that "a new dawn has broken, has it not?"

The election was a crushing defeat for the Conservative Party, with the party having its lowest percentage share of the popular vote since 1832 under the Duke of Wellington's leadership, being wiped out in Scotland and Wales. A number of prominent Conservative MPs lost their seats in the election, including Michael Portillo, Malcolm Rifkind, Edwina Currie, David Mellor, Neil Hamilton and Norman Lamont. Such was the extent of Conservative losses at the election that Cecil Parkinson, speaking on the BBC's election night programme, joked upon the Conservatives winning their second seat that he was pleased that the subsequent election for the leadership would be contested.

The Liberal Democrats stood on a more left-wing manifesto than Labour,[23][24] and more than doubled their number of seats thanks to the use of tactical voting against the Conservatives.[9] Although their share of the vote fell slightly, their total of 46 MPs was the highest for any UK Liberal party since David Lloyd George led the party to 59 seats in 1929.

The Referendum Party, which sought a referendum on the United Kingdom's relationship with the European Union, came fourth in terms of votes with 800,000 votes and won no seats in parliament.[25]

The six parties with the next highest votes stood only in either Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales; in order, they were the Scottish National Party, the Ulster Unionist Party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, Plaid Cymru, Sinn Féin, and the Democratic Unionist Party.

In the previously safe seat of Tatton, where incumbent Conservative MP Neil Hamilton was facing charges of having taken cash for questions, the Labour and Liberal Democrat parties decided not to field candidates in order that an independent candidate, Martin Bell, would have a better chance of winning the seat, which he did with a comfortable margin.

The result declared for the constituency of Winchester showed a margin of victory of just two votes for the Liberal Democrats. The defeated Conservative candidate mounted a successful legal challenge to the result on the grounds that errors by election officials (failures to stamp certain votes) had changed the result; the court ruled the result invalid and ordered a by-election on 20 November which was won by the Liberal Democrats with a much larger majority, causing much recrimination in the Conservative Party about the decision to challenge the original result in the first place.

This election saw a doubling of the number of women in parliament, from 60 elected in 1992 to 120 elected in 1997.[26] 101 of them (controversially described as Blair Babes) were on the Labour benches,[27] a number driven by the Labour Party's 1993 policy (ruled illegally discriminatory in 1996) of all-women shortlists. This election has therefore been widely seen as a watershed moment for representation of women in the UK.[28][29][30][31]

This election marked the start of Labour government for the next 13 years, lasting until the formation of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010.

| Candidates | Votes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Leader | Stood | Elected | Gained | Unseated | Net | % of total | % | No. | Net % | |

| Labour | Tony Blair | 639 | 418 | 146 | 0 | +146 | 63.4 | 43.2 | 13,518,167 | +8.8 | |

| Conservative | John Major | 648 | 165 | 0 | 178 | –178 | 25.0 | 30.7 | 9,600,943 | –11.2 | |

| Liberal Democrats | Paddy Ashdown | 639 | 46 | 30 | 2 | +28 | 7.0 | 16.8 | 5,242,947 | –1.0 | |

| Referendum | James Goldsmith | 547 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | 811,849 | N/A | ||

| SNP | Alex Salmond | 72 | 6 | 3 | 0 | +3 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 621,550 | +0.1 | |

| Ulster Unionist | David Trimble | 16 | 10 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 258,349 | 0.0 | |

| SDLP | John Hume | 18 | 3 | 0 | 1 | –1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 190,814 | +0.1 | |

| Plaid Cymru | Dafydd Wigley | 40 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 161,030 | 0.0 | |

| Sinn Féin | Gerry Adams | 17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | +2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 126,921 | 0.0 | |

| DUP | Ian Paisley | 9 | 2 | 0 | 1 | –1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 107,348 | 0.0 | |

| UKIP | Alan Sked | 193 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 105,722 | N/A | ||

| Independent | N/A | 25 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 64,482 | 0.0 | |

| Alliance | John Alderdice | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 62,972 | 0.0 | ||

| Green | Peg Alexander and David Taylor | 89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 61,731 | –0.2 | ||

| Socialist Labour | Arthur Scargill | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 52,109 | N/A | ||

| Liberal | Michael Meadowcroft | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 45,166 | –0.1 | ||

| BNP | John Tyndall | 57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 35,832 | 0.0 | ||

| Natural Law | Geoffrey Clements | 197 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 30,604 | –0.1 | ||

| Speaker | Betty Boothroyd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 23,969 | |||

| ProLife Alliance | Bruno Quintavalle | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 19,332 | N/A | ||

| UK Unionist | Robert McCartney | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | +1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 12,817 | N/A | |

| PUP | Hugh Smyth | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10,928 | N/A | ||

| National Democrats | Ian Anderson | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10,829 | N/A | ||

| Socialist Alternative | Peter Taaffe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,906 | N/A | |||

| Scottish Socialist | Tommy Sheridan | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,740 | N/A | ||

| Independent | N/A | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 9,233 | – 0.1 | ||

| Ind. Conservative | N/A | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8,608 | –0.1 | ||

| Monster Raving Loony | Screaming Lord Sutch | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7,906 | –0.1 | ||

| Make Politicians History | Rainbow George Weiss | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,745 | N/A | ||

| NI Women's Coalition | Monica McWilliams and Pearl Sagar | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3,024 | N/A | ||

| Workers' Party | Tom French | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,766 | –0.1 | ||

| National Front | John McAuley | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,716 | N/A | ||

| Cannabis Law Reform | Howard Marks | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2,085 | N/A | ||

| Socialist People's Party | Jim Hamezian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,995 | N/A | ||

| Mebyon Kernow | Loveday Jenkin | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,906 | N/A | ||

| Scottish Green | Robin Harper | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,721 | |||

| Conservative Anti-Euro | Christopher Story | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,434 | N/A | ||

| Socialist (GB) | None | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,359 | N/A | ||

| Community Representative | Ralph Knight | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,290 | N/A | ||

| Neighborhood association | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,263 | N/A | |||

| SDP | John Bates | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,246 | –0.1 | ||

| Workers Revolutionary | Sheila Torrance | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,178 | N/A | ||

| Real Labour | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1,117 | N/A | ||

| Independent Democrat | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 982 | ||||

| Independent | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 890 | ||||

| Communist | Mike Hicks | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 639 | |||

| Independent | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 593 | |||

| Green (NI) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 539 | ||||

| Socialist Equality | Davy Hyland | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 505 | |||

The Popular Unionist MP elected in 1992 died in 1995, and the party folded shortly afterwards.

There was no incumbent Speaker in the 1992 election.| Government's new majority | 179 |

| Total votes cast | 31,286,284 |

| Turnout | 71.3% |

Results by constituent country edit

| LAB | CON | LD | SNP | PC | NI parties | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 328 | 165 | 34 | - | - | - | 2 | 529 |

| Wales | 34 | - | 2 | - | 4 | - | - | 40 |

| Scotland | 56 | - | 10 | 6 | - | - | - | 72 |

| Northern Ireland | - | - | - | - | - | 18 | - | 18 |

| Total | 418 | 165 | 46 | 6 | 4 | 18 | 2 (inc Speaker) | 659 |

Defeated MPs edit

MPs who lost their seats edit

Post-election events edit

The poor results for the Conservative Party led to infighting, with the One Nation group, Tory Reform Group, and right-wing Maastricht Rebels blaming each other for the defeat. Party chairman Brian Mawhinney said on the night of the election that defeat was due to disillusionment with 18 years of Conservative rule. John Major resigned as party leader, saying "When the curtain falls, it is time to get off the stage".[32]

Following the defeat, the Conservatives began their longest continuous spell in opposition in the history of the present day (post–Tamworth Manifesto) Conservative Party - and indeed the longest such spell for any incarnation of the Tories/Conservatives since the 1760s and the end of the Whig Supremacy under Kings George I and George II - lasting 13 years, including the whole of the 2000s.[33] Throughout this period, their representation in the Commons remained consistently below 200 MPs.

Meanwhile, Paddy Ashdown's continued leadership of the Liberal Democrats was assured, and they were felt to be in a position to build positively as a strong third party into the new millennium,[34] culminating in their sharing power in the 2010 coalition with the Conservatives.

Internet coverage edit

With the huge rise in internet use since the previous general election, BBC News created a special website – BBC Politics 97 – covering the election.[35] This site was an experiment for the efficiency of an online news service which was due for launch later in the year.[36]

See also edit

Footnotes edit

- ^ Conservative party leader John Major resigned as Leader of the Conservative Party on 22 June 1995 to face critics in his party and government, and was reelected as Leader on 4 July 1995. Prior to his resignation, he had held the post of Leader of the Conservative Party since 28 November 1990.[2]

References edit

- ^ "1997 - Registered voters".

- ^ "1995: Major wins Conservative leadership". BBC News. 4 July 1995. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ "UK Politics - The Major Scandal Sheet". BBC News.

- ^ Miers, David (2004). Britain in the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 12–36. doi:10.1057/9780230523159_2. ISBN 978-1-4039-0452-2. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "The Polls and the British General Election of 1997". www.ipsos.com. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Blair ahead in leadership ratings". BBC News. 3 May 2001. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ a b Greenslade, Roy (18 March 1997). "It's the Sun wot's switched sides to back Blair". The Guardian.

- ^ "BBC Politics 97 - Background". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Hermann, Michael; Munzert, Simon; Selb, Peter (4 November 2015). "The conventional wisdom about tactical voting is wrong". London School of Economics British Politics and Policy blog. London School of Economics. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "The Election. The Statistics. How the UK voted on May 1st". BBC Politics 97. BBC News. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Harman, Harriet (10 April 2017). "Labour's 1997 victory was a watershed for women but our gains are at risk". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "1997: Labour landslide ends Tory rule". BBC News. 15 April 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "House of Lords Debates vol 579 cc653-4: Dissolution of Parliament". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 17 March 1997. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ Hencke, David (19 March 1997). "Fury as sleaze report buried". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ "Advertising & Promotion: Ads contract election fever". Campaign. 20 March 1997. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ a b Snowdon 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Travis, Alan (17 April 1997). "Rebels' seven-year march". The Guardian (London).

- ^ Bevins, Anthony (17 April 1997). "Election '97: John Major takes on the Tories". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Snowdon 2010, p. 35.

- ^ Tiltman, David (1 May 2007). "The New Labour brand 10 years on". campaignlive.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

In keeping with the New Labour message, the party's 1997 campaign attacked the economic record of the Tories following 1992's Black Wednesday and promised national renewal, memorably using D:Ream's song Things Can Only Get Better.

- ^ Gillett, Ed (22 July 2023). "'From the dancefloor to the ballot box': how house music helped Labour win a landslide in 1997". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

First released in 1993, but only lightly grazing the Top 40 on its initial foray into the charts, a poppier remix of D:Ream's Things Can Only Get Better spent four weeks at No 1 the following January. Two years on from that, it was co-opted for the launch of Labour's five "pre-manifesto" pledges, written largely by Tony Blair himself. Something in the song's message clearly resonated with Labour apparatchiks, or tested well with the party's army of focus groups: by the time the election came around in May 1997, Things Can Only Get Better had displaced The Red Flag as New Labour's election anthem, the feelgood sonic backdrop to rallies, photo opportunities and campaign adverts alike.

- ^ Stoddard, Katy (4 May 2010). "Newspaper support in UK general elections". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Ben Pimlott (October 1997). "New Labour, New Era?". The Political Quarterly. 68 (4): 325–334. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.00099.

- ^ Geoffrey Evans; Pippa Norris (1999). "14 - Conclusion: Was 1997 a Critical Election?". Critical elections: British parties and voters in long-term perspective. SAGE Publishing. pp. 259–271.

- ^ a b Morgan, Bryn (February 1999). "General Election Results, 1 May 1997" (PDF). Factsheet No. 68. House of Commons Information Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Richard (21 August 2018). "Women in the House of Commons: Background Paper". House of Commons Library. UK Parliament. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Harriet Harman (10 April 2017). "Labour's 1997 victory was a watershed for women – but our gains are at risk". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Flint, Caroline; Spelman, Caroline (4 May 2017). "How the Class of '97 Changed Westminster". Politics Home - The House. Politics Home. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Kirk, Ashley; Scott, Patrick (17 June 2017). "General election 2017 sees record number of women candidates". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ Blaxill, Luke; Beelen, Kaspar (25 July 2016). "Women in Parliament since 1945: have they changed the debate?". History & Policy - Policy Papers. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

We suggest that 1997 was significant because it helped normalise a large female presence at Westminster which absolved women MPs of the obligation to act as 'token women' and thus as spokeswomen for their sex.

- ^ Childs, Sarah (2000). "The new labour women MPs in the 1997 British parliament: issues of recruitment and representation". Women's History Review. 9 (1). Routledge (Taylor & Francis): 55–73. doi:10.1080/09612020000200228. ISSN 1747-583X.

The research suggests that women MPs consider that women's presence has the potential to transform the parliamentary political agenda and style.

- ^ "Major players: The 1990 generation". TotalPolitics.com. 3 January 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Kettle, Martin (13 May 2010). "Tories rule: but liberal Tories with a New Labour legacy". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "BBC Politics 97". BBC Politics 97. BBC News. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "BBC Politics 97". BBC Politics 97. BBC News. 1997. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ^ "Major events influenced BBC's news online | FreshNetworks blog". Freshnetworks.com. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

Further reading edit

- Butler, David and Dennis Kavanagh. The British General Election of 1997 (1997), the standard scholarly study

- Snowdon, Peter (2010) [2010]. Back from the Brink: The Extraordinary Fall and Rise of the Conservative Party. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-730884-2.

Manifestos edit

- Labour (New Labour, New Life For Britain)

- Conservative (You can only be sure with the Conservatives)

- Liberal Democrats (Make the Difference)

- National Democrats (A Manifesto for Britain)

- British National Party (British Nationalism- An Idea whose time has come)

- Liberal Party (Radical ideas – not the dead centre)

- UK Independence Party

- Third Way

- The ProLife Alliance

- Sinn Féin (A New Opportunity for Peace)

- Democratic Unionist Party

- Alliance of Liberty (Agenda for Change)

- Progressive Unionist Party

- Ulster Unionist Party

- Plaid Cymru (The Best for Wales)

- Scottish National Party (Yes We Can Win the Best for Scotland)

- Scottish Green Party

- Socialist Equality Party (A strategy for a workers' government!)

- Communist Party of Great Britain

External links edit

- BBC Election Website

- 1997 election manifestos – Link to 1997 election manifestos of various parties.

- Catalogue of 1997 general election ephemera at the Archives Division of the London School of Economics.