Summary

Absence of Malice is a 1981 American drama neo noir thriller film directed by Sydney Pollack and starring Paul Newman, Sally Field, Wilford Brimley, Melinda Dillon and Bob Balaban.

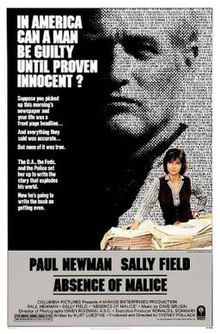

| Absence of Malice | |

|---|---|

Promotional poster | |

| Directed by | Sydney Pollack |

| Written by | Kurt Luedtke David Rayfiel (uncredited) |

| Produced by | Sydney Pollack Ronald L. Schwary |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Owen Roizman |

| Edited by | Sheldon Kahn |

| Music by | Dave Grusin |

| Color process | Color by DeLuxe |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $40.7 million |

The title refers to one of the defenses against libel defamation, and is used in journalism classes to illustrate the conflict between disclosing damaging personal information and the public's right to know.[1]

Plot edit

Miami liquor wholesaler Michael Gallagher, who is the son of a deceased criminal, awakens one day to find himself a front-page story in the local newspaper. The paper indicates that he is being investigated in the disappearance and presumed murder of a local longshoremans' union official, Joey Diaz.

The story was written by Miami Standard newspaper reporter Megan Carter, who reads it from a file left intentionally on the desktop of federal prosecutor Elliot Rosen. As it turns out, Rosen is doing a bogus investigation and has leaked it with the purpose of squeezing Gallagher for information.

Gallagher comes to the newspaper's office trying to discover the basis for the story, but Carter does not reveal her source. Gallagher's business is shut down by union officials who are now suspicious of him since he has been implicated in Diaz's murder. Local crime boss Malderone, Gallagher's uncle, has him followed, just in case he talks to the government.

Teresa Perrone, a lifelong friend of Gallagher, tells the reporter that Gallagher could not have killed Diaz because Gallagher took her out of town to get an abortion that weekend. A devout Catholic, she does not want Carter to reveal the abortion, but Carter includes it in the story anyway. When the paper comes out the next morning, Perrone picks up the copies from her neighbors' yards before they can be read. Later, offscreen, she kills herself.

The paper's editor tells Carter that Perrone has died by suicide. Carter goes to Gallagher to apologize, but an enraged Gallagher assaults her. Nevertheless, she attempts to make it up to him by revealing Rosen's role in the investigation.

Gallagher hatches a plan for revenge. He arranges a secret meeting with District Attorney Quinn, offering to use his organized-crime contacts to give Quinn exclusive information on Diaz's murder in exchange for the D.A. calling off the investigation and issuing a public statement clearing him. Both before his meeting with Quinn and after Quinn's public statement, Gallagher makes significant anonymous contributions to one of Quinn's political action committee backers. Gallagher, thankful for Carter's help, also begins a love affair with her.

Rosen is mystified by Quinn's exoneration of Gallagher, so he places phone taps on both and begins a surveillance of their movements. He and federal agent Bob Waddell obtain evidence of Gallagher's donations to Quinn's political committee. They also find out about Gallagher and Carter's relationship. Waddell, as a friend, warns Carter about the investigation to keep her out of trouble. But she breaks the story that the federal strike force is investigating Gallagher's attempt to bribe the D.A.

The story makes the front page again and causes an uproar over the investigation of the district attorney. Assistant US Attorney General Wells ultimately calls all of the principals together. He offers them a choice between going before a grand jury and informally making their case to him. Rosen questions Gallagher but it quickly becomes apparent that he has no case, and Carter reveals that Rosen left the file on Gallagher open on his desk for her to read.

After the truth comes out, Wells suggests Quinn resign as Gallagher's legal donations to Quinn's political committee cast suspicions on Quinn's motives in issuing his statement clearing Gallagher. Wells also suspects that Gallagher set everything up, but cannot prove it, so he will not investigate further. Attempting to rebuke Gallagher, Wells tells him not to "get too smart," noting that he himself is "a pretty smart fella" to which Gallagher replies: "Everybody in this room is pretty smart and everybody is just doing their job. And Teresa Perrone is dead... Who do I see about that?" Finally, Wells fires Rosen for malfeasance. The newspaper now prints a new story written by a different reporter revealing details of the incidents.

It is unclear whether Carter keeps her job, or whether Carter's relationship with Gallagher will continue, but the final scene shows them having a cordial conversation on the wharf where Gallagher's boat is docked before he sails away and leaves the city.

Cast edit

- Paul Newman as Gallagher

- Sally Field as Megan Carter

- Bob Balaban as Rosen

- Melinda Dillon as Teresa Perrone

- Luther Adler as Malderone

- Barry Primus as Waddell

- Josef Sommer as McAdam

- John Harkins as Davidek

- Don Hood as Quinn

- Wilford Brimley as Wells

Production edit

The movie was written by Kurt Luedtke, a former newspaper editor, and David Rayfiel (uncredited).[2] Newman said that the film was a "direct attack on the New York Post," which had earlier published a caption for a photo of Newman that he said was inaccurate. Because of the dispute, the Post banned Newman from its pages, even removing his name from movies in the TV listings.[3]

Reception edit

Critical response edit

Absence of Malice received mostly positive reviews. Newman and Dillon's performances were praised, as was Brimley's cameo. Many reviewers compared the film to the 1976 Oscar–winner All the President's Men. In his review, Time magazine's Richard Schickel wrote "Absence of Malice does not invalidate All the President's Men. But with entertainment values – and a moral sense – every bit as high as that film's, it observes that there is an underside to journalistic gallantry."[4] Similarly, Variety called it "a splendidly disturbing look at the power of sloppy reporting to inflict harm on the innocent."[5]

The Chicago Sun-Times' Roger Ebert wrote that some may take the approach "that no respectable journalist would ever do the things that Sally Field does about, to, and with Paul Newman in this movie. She is a disgrace to her profession." Instead he preferred a "romantic" approach, writing that he "liked this movie despite its factual and ethical problems" and was not "even so sure they matter so much to most viewers".[6] Janet Maslin of The New York Times found the movie "lacking in momentum", but praised its "quiet gravity".[7] Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader disliked Absence of Malice, writing that "the picture has a smug, demoralizing sense of pervasive corruption".[8] Although Pauline Kael described the film as only "moderately entertaining", she offered higher praise for Newman's "sly, compact performance" and particularly for "the marvelously inventive acting of Melinda Dillon".[9]

Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 81% based on reviews from 27 critics, with an average score of 6.8/10.[10]

Academic use edit

Absence of Malice has been used in journalism and public administration courses to illustrate professional errors such as writing a story without seeking confirmation and having a romantic relationship with a source.[11][12][13]

Box office edit

The film was a box office success. Film Comment said "It was the first picture in ages that had Newman playing opposite a strong female co-star in a romantic vein and Columbia astutely capitalized on public desire to see Newman in such a role again."[14]

Accolades edit

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Actor | Paul Newman | Nominated | [15] |

| Best Supporting Actress | Melinda Dillon | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | Kurt Luedtke | Nominated | ||

| Berlin International Film Festival | Golden Bear | Sydney Pollack | Nominated | [16] |

| Honourable Mention | Won | |||

| Reader Jury of the "Berliner Morgenpost" | Won | |||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama | Sally Field | Nominated | [17] |

| Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | Kurt Luedtke | Nominated | ||

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Supporting Actress | Melinda Dillon | Won | [18] |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards | Best Supporting Actress | Runner-up | [19] | |

| Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Drama – Written Directly for the Screen | Kurt Luedtke | Nominated | [20] |

References edit

- ^ Absence of Malice (1981) Archived January 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine When bad journalism kills, By Lauren Kirchner, Columbia Journalism Review, July 15, 2011

- ^ "Absence of Malice (1981)," Archived September 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Internet Movie Database. Accessed March 20, 2012.

- ^ DiGiaomo, Frank (December 2004). "The Gossip Behind the Gossip". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Schickel, Richard. "Cinema: Lethal Leaks" Archived March 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Time magazine (November 23, 1981).

- ^ "Absence of Malice", Variety (December 31, 1980).

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Absence of Malice movie review (1981) | Roger Ebert". rogerebert. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet. "MOVIE REVIEW: NYT Critics' Pick: Absence of Malice", The New York Times (November 19, 1981)

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "Absence of Malice" Archived November 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Reader. Accessed March 20, 2012.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (2011) [1991]. 5001 Nights at the Movies. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-250-03357-4. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "Absence of Malice (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ Kirchner, Lauren (July 15, 2011). "Absence of Malice (1981): When Bad Journalism Kills". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Borins, Sanford (December 12, 2015). "Absence of Malice: Learning from Mistakes". Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ Stocking, Holly R. (2008). "What is Good Work? Absence of Malice". In Good, Howard (ed.). Journalism Ethics Goes to the Movies. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 49. ISBN 9780742554283. OCLC 137305773.

- ^ Meisel, Myron (Mar/Apr 1982). "Seventh Annual Grosses Gloss". Film Comment; New York Vol. 18, Iss. 2: 60–66, 80.

- ^ "The 54th Academy Awards (1982) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- ^ "Berlinale 1982: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ "Absence of Malice – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1980-89". December 14, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "The 7th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

External links edit

- Absence of Malice at IMDb

- Absence of Malice at the TCM Movie Database

- Absence of Malice at Box Office Mojo