Summary

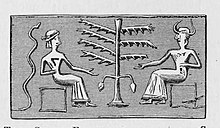

The Adam and Eve cylinder seal, also known as the "temptation seal", is a small stone cylinder of post-Akkadian origin, dating from about 2200 to 2100 BCE. The seal depicts two seated figures, a tree, and a serpent, and was formerly believed to evince some connection with Adam and Eve from the Book of Genesis. It is now seen as a conventional example of an Akkadian banquet scene.[2]

| Adam and Eve cylinder seal | |

|---|---|

Drawing of the seal's impression, by George Smith[1] | |

| Material | greenstone |

| Size | h x d: 2.71 cm (1.07 in) x 1.65 cm (0.65 in) |

| Created | 22nd century BCE |

| Present location | British Museum |

| Identification | 1846,0523.347 |

History edit

Cylinder seals are small cylinders, usually made of stone and pierced from end-to-end. They are designed to be worn on a string or on a pin.

Designs are carved into the surface of cylinders seals in intaglio, so that when rolled on clay, the cylinder leaves a continuous imprint of the design, reversed and in relief. Cylinder seals originate from southern Mesopotamia (now Iraq) or south-western Iran. They were invented around 3500 BC, and were used as an administrative tool, as magical amulets and as jewellery until around 300 BC. They are linked to the invention of cuneiform writing on clay; when this spread to other areas of the Near East, the use of cylinder seals spread as well.[3]

Assyriologist George Smith described the Adam and Eve seal as having two figures (male and female) on each side of a tree, holding out their hands to the fruit, while between the backs of the figures is a serpent, which he saw as evidence that the Fall of Man legend was known in early times of Babylonia.[1][3][4]

Description edit

According to Dominque Collon, the seal shows a common scene found on seals from the twenty-third and twenty-second centuries BC: a seated male figure (identified by his head-dress of horns as a god) facing a female worshiper. The date palm and snake between them may merely be symbolic of fertility.[5] This view is backed by David L. Petersen, who writes that:

Collon rightly maintains that this particular seal belongs in the well-established tradition of the Akkadian banquet scene. In order to prove her case, she points to several features in the so-called "Adam and Eve" seal that may be found in contemporary images. First, there is a long tradition in Mesopotamian art of representing figures facing a central plant, here a date palm. Also, the horns of the seated figure on the right indicate divine status, in accordance with long-held iconographic conventions. The identity of the figure on the left is probably a worshiper, and not a woman at all, as Fradenburgh assumed. As for the snake, it may well be a representation of a snake-god (such as Nirah) or possibly a more general symbol of regeneration and fertility.[6]

The professor in comparative mythology and comparative religion Joseph Campbell sees in it a cult that has probably emerged and developed in the Neolithic period presenting the mother goddess associated with the Tree of Life and the serpent. He writes:

"Hence the early Sumerian seal figure cannot possibly be, as some scholars have supposed, the representation of a lost Sumerian version of the Fall of Adam and Eve. Its sprits is that of the idyll in the much earlier, Bronze Age view of the garden of innocence, where the two desirable fruits of the mythic date palm are to be culled: the fruit of enlightenment and the fruit of immortal life. The female figure at the left, before the serpent, is almost certainly the goddess Gula-Bau (a counterpart, as we have said of Demeter and Persephone) while male on the right, who is not mortal but a god, as we know from his horned lunar crown, is no less surely his beloved son-husband Dumuzi, Son of the Abyss: Lord of the Tree of Life [...]".[7]

References edit

- ^ a b Smith, George (1876). The Chaldean Account of Genesis. New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., pp. 90–91

- ^ Petersen, David L. (2009). Method Matters: Essays on the Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of David L. Petersen. Society of Biblical Lit. ISBN 9781589834446.

Collon rightly maintains that this particular seal belongs in the well-established tradition of the Akkadian banquet scene. In order to prove her case, she points to several features in the so-called "Adam and Eve" seal that may be found in contemporary images. First, there is a long tradition in Mesopotamian art of representing figures facing a central plant, here a date palm. Also, the horns of the seated figure on the right indicate divine status, in accordance with long-held iconographic conventions. The identity of the figure on the left is probably a worshiper, and not a woman at all, as Fradenburgh assumed. As for the snake, it may well be a representation of a snake-god (such as Nirah) or possibly a more general symbol of regeneration and fertility.

- ^ a b "'Adam and Eve' cylinder seal". British Museum via Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, T.C. (2004). The Bible in the British Museum : interpreting the evidence (New ed.). New York: Paulist Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780809142927.

- ^ "'Adam and Eve' cylinder seal". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (Dead link. Archived version.) - ^ Petersen, David L. (2009). Method Matters: Essays on the Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of David L. Petersen. Society of Biblical Lit. ISBN 9781589834446.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (1976). The masks of God Vol III- Occidental mythology. Penguin Books. p.14.