Summary

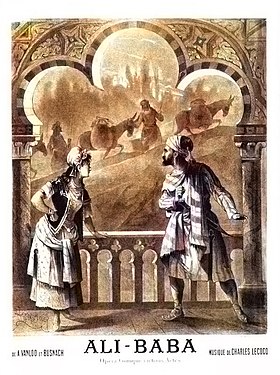

Ali-Baba is an opéra comique in three acts, first produced in 1887, with music by Charles Lecocq. The French libretto based on the familiar tale from the Arabian Nights was by Albert Vanloo and William Busnach.[1] After some initial success the work faded from the repertoire.

Performance history edit

Ali Baba was a popular subject for operas (Cherubini, 1833, Bottesini, 1871), pantomimes and extravaganzas in Paris and London during the nineteenth century.[2] Both librettists were experienced in opéra-bouffe and had previously worked with Lecocq, Busnach from 1866 with Myosotis, Vanloo starting in 1874 with Giroflé-Girofla; the two men had met in 1868 when Vanloo had submitted an opéra-bouffe for consideration to Busnach who was at the time the director of the Théâtre de l'Athénée.[3]

Originally intended for the Théâtre de la Gaîté in Paris, Lecocq's opera was premiered in a sumptuous production at an established home of operetta and revue in Brussels, the 2,500-seat Théâtre Alhambra, on 11 November 1887.[3] It opened at the Éden-Théâtre, Paris, on 28 November 1889 in three acts and nine tableaux with Morlet in the title role and Jeanne Thibault as Morgiane.[4] The Annales critic considered that the first act was the strongest of a dense score which had seven numbers from the first run in Brussels removed for the Paris production.[4]

In May 2014 the Paris Opéra-Comique mounted a new production directed by Arnaud Meunier and conducted by Jean-Pierre Haeck.[5]

Roles edit

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 11 November 1887[6] (Conductor: ) |

|---|---|---|

| Morgiane | soprano | Juliette Simon-Girard |

| Zobéïde | mezzo-soprano | Duparc |

| Medjéah | soprano | Cannès |

| Ali-Baba | baritone | Dechesne |

| Zizi | tenor | Simon-Max |

| Cassim | tenor | Mesmacker |

| Saladin | tenor | Larbaudière |

| Kandgiar | baritone | Chalmin |

| Robbers, merchants, townspeople, old Turks; dancers | ||

Synopsis edit

Setting : Bagdad

Act 1 edit

In the shop of Cassim, Saladin, the chief clerk, woos Morgiane, the young slave of Ali-Baba. Despite his urging, she is unmoved. Their conversations are interrupted by an argument between Cassim and Zobéïde, his wife. The merchant is impatient to recover unpaid debt from his cousin Ali-Baba. Cassim tells his wife that if he does not receive the money owing, he will seize Ali-Baba's property. Poor Ali-Baba has returned to working as a wood-chopper and considers suicide, so desperate is his situation. Morgiane comes in and dissuades him; she reminds him how he saved her when she was a maltreated little girl. Alone again, Ali-Baba is disturbed by masked men on horseback. He conceals himself and his donkey and realizes that the men are a band of thieves. With the magic words "open sesame", the head of the gang gets the cave to open and his men take their booty to hide. Once the thieves have left, Ali-Baba says the same words and enters the cave. In the town square, cadi Maboul has seized pieces of furniture from the home of Ali-Baba at the request of Cassim, in spite of Zobéïde's protests. When the crowd hesitates to buy the property, the cadi suggests selling Morgiane. In time, Ali-Baba returns, enriched by what he has found in the cave. While Ali-Baba distributes gold, Cassim, amazed at this sudden affluence, suspects his wife of having given money to his cousin.

Act 2 edit

Morgiane waits for her master at Ali-Baba's house, near Cassim's. He appears in sumptuous apparel and recounts to her how he has come by his wealth, unaware that Cassim is listening. In possession of the magic formula, Cassim rushes to gang's cave to help himself. As he is about to leave, he realizes that he has forgotten the magic words. Cassim is caught by the forty thieves and condemned to die. However, he manages to make a deal with Zizi, his former worker and now a member of the gang of thieves, who saves his life by disguising him and giving him a new name, Casboul, making him swear to forget his past life.

Act 3 edit

Her husband not having come home, Zobéïde tells Ali-Baba about his disappearance. Ali-Baba realizes that Cassim went to the cave and goes looking for him, returning with his discarded clothes. Believing her husband dead, Zobéïde collapses in tears. Meanwhile, Kandgiar, the thieves' leader, roams the streets begging in order to track down the one who managed to raid his hidden treasure. Eventually he is given a coin which he recognizes as one he himself had stolen. Ali-Baba, who has given him this generous alm, is the guilty one. Kandgiar tells one of his men to mark with a cross Ali-Baba's home, so the gang can descend upon it the following night. Morgiane foils his plans by marking all the neighbouring houses with the same sign; despite trying again with a red cross, the thieves are again thwarted. Ali-Baba receives Zobéïde in his palace. She has always loved her poor cousin and suggests that they marry. Her husband, disguised as a secretary beside Zizi, witnesses this. Zobéïde and Ali-Baba agree to have their wedding that very evening, during the Feast of the Candles. That night, Kandgiar, disguised as a merchant, requests hospitality. Morgiane again senses a trap, guesses that the forty thieves are in the cellar, and alerts the cadi. The bandits are arrested and condemned to death, but Cassim, Zizi, and Kandgiar are still at large. The celebrations take place in the gardens of Ali-Baba. Kandgiar has commissioned a dancer to murder Ali-Baba. However, again Morgiane thwarts his plans and saves her master. Finally free of the thieves, Cassim returns to his former life, Ali-Baba asks for Morgiane's hand, and Zizi is forgiven.

References edit

- ^ Lamb, A.; Gänzl, K. "Charles Lecocq". In: The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

- ^ Gänzl K. Ali Baba – in The Encyclopaedia of the Musical Theatre. Blackwell, Oxford, 1994.

- ^ a b Opéra-Comique Dossier Pédagogique: Ali-Baba (Anne Le Nabour (2013)

- ^ a b Noël E & Stoullig E. Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, 15ème édition, 1889. G Charpentier, Paris, 1890, pp. 393–96.

- ^ Opéra-Comique website, 2013/14 season

- ^ "Choudens vocal score, IMSLP pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

External links edit

- Ali-Baba (Lecocq): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project