Summary

Aliceville is a city in Pickens County, Alabama, United States, located thirty-six miles west of Tuscaloosa. At the 2010 census its population was 2,486, down from 2,567 in 2000. Founded in the first decade of the 20th century and incorporated in 1907,[2] the city has become notable for its World War II-era prisoner-of-war camp, Camp Aliceville. Since 1930, it has been the largest municipality in Pickens County.[3]

Aliceville, Alabama | |

|---|---|

Street Scene in Aliceville | |

Flag  Seal | |

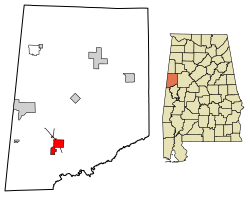

Location of Aliceville in Pickens County, Alabama. | |

| Coordinates: 33°7′34″N 88°9′15″W / 33.12611°N 88.15417°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Pickens |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.57 sq mi (11.84 km2) |

| • Land | 4.57 sq mi (11.84 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 194 ft (59 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 2,177 |

| • Density | 476.37/sq mi (183.94/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 35442 |

| Area codes | 205, 659 |

| FIPS code | 01-01228 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0112988 |

| Website | www |

History edit

In 1902 the settlement that would become Aliceville was founded with the opening of a single store.[4] The city was named in honor of the wife of John T. Cochrane, founder of the Alabama, Tennessee and Northern Railroad and moving force behind the construction of the short line from Carrollton, Alabama to Aliceville.[5] Within two years of the completion of the short line, Aliceville had grown to what the Montgomery Advertiser called in 1905 "a town of considerable pretensions. There are about a dozen stores, a bank, public buildings and numerous enterprises."[6]

In 1907 an election was scheduled to allow the citizens of Aliceville to decide whether their community should be incorporated.[7] Incorporation was approved by the voters, and on March 19, 1907, a municipal election was held to choose municipal officers, including a mayor and five aldermen: T.H. Sommerville, J.M. Summerville, A. Hood, J.D. Sanders, W.E. Stringfellow, and J.B. Cunningham, respectively.[8]

In August 1907 a black man named Gibson was lynched in Aliceville, which caused civil disturbances in the community.[9] Rumors swirled that "the negroes were arming themselves," and a group of blacks on horseback were fired on in the street.[9] Gibson's father was subsequently "ordered to leave the county on account of some impertient (sic) talk."[9]

By March 1908, municipal officials had decreed that all streets should have ten-foot sidewalks built on both sides.[10] Property owners were to be responsible for building the sidewalks in front of their parcels.[10] This work, along with the paving of the streets, was largely completed by June 1910 and the city began considering the installation of water and electricity.[11]

Camp Aliceville edit

During World War II, a Prisoner-of-war camp was set up in Aliceville to hold 6,000 German prisoners, most from the Afrika Korps, although the population of the camp rarely exceeded 3,500.[12] The camp operated between June 2, 1943[12] and September 30, 1945.[13] Prisoners were brought to the camp via the St. Louis – San Francisco Railway.[12]

The only remaining trace of the camp is an old stone chimney.[13] However, there is a German POW collection at the Aliceville Museum and Cultural Arts Center[14] which retains documentation from the camp including maps, photographs, camp publications, letters, and artwork.[15]

Civil rights movement edit

1960 edit

During the civil rights movement, organizing in small communities such as Aliceville was often more dangerous for activists than it was in larger cities because of their isolation.[16] As late as 1965, according to James Corder, a Primitive Baptist minister from Aliceville, Pickens County had not yet experienced any civil unrest related to the movement.[16] Jordan was inspired by the Selma to Montgomery marches in March of that year to organize a civil rights group in Aliceville, which he called the "Rural Farm and Development Council" in order to avoid scrutiny.[16] The group organized protests at the Aliceville city hall to oppose officially sanctioned racism in the city.[16]

In September 1969 black students held protests against the principal of an all-black school in Aliceville, prompting governor Albert Brewer to send National Guard troops into the city.[17] Two of the city's all-black schools were closed on September 4 due to the demonstrations, and they reopened the next day under National Guard supervision.[18]

1970s and 1980s edit

In 1982, Aliceville native Maggie Bozeman testified at Congressional hearings held in Montgomery, Alabama, concerning proposed amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[19] She testified that as late as 1980 in Aliceville and Pickens County voting took place in the open rather than in private booths and that white police officers were stationed in polling places, taking photographs of people who assisted black voters.[20] This revelation outraged Republican congressman Henry Hyde, who had previously been unconvinced of the necessity of amending the law.[19]

Bozeman's testimony followed her 1979[21] arrest, conviction, and sentencing for vote fraud.[22] Bozeman and fellow political activist Julia Wilder of Olney, Alabama were given "the sternest sentences for a vote fraud conviction in recent Alabama history": five years for Wilder and four for Bozeman.[22] The sentences were upheld on appeal, prompting the formation of an organization, the National Coalition to Free Julia Wilder and Maggie Bozeman and Save the Voting Rights Act, and a march through Aliceville from Carrollton, Alabama, to Montgomery to publicize their cause.[22]

The United States Department of Justice sent eight poll-watchers to Aliceville to observe the 1984 primary election runoffs following reports from observers of the July 1984 main primaries.[23]

And after edit

In November 2013 three tanker cars carrying crude oil exploded when an Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway train derailed near Aliceville.[24] As of March 2014, the cleanup of the spilt oil was still not complete, despite four months of work.[25] About 750,000 gallons of Bakken crude was released.[26]

Geography edit

Aliceville is located at 33°7′35″N 88°9′16″W / 33.12639°N 88.15444°W (33.126276, -88.154427).[27] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.5 square miles (12 km2), all land.

Climate edit

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Aliceville has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[28]

| Climate data for Aliceville, Alabama, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1934–2022 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

93 (34) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

88 (31) |

83 (28) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 73.1 (22.8) |

76.4 (24.7) |

81.8 (27.7) |

84.8 (29.3) |

90.4 (32.4) |

94.7 (34.8) |

97.4 (36.3) |

97.0 (36.1) |

94.8 (34.9) |

88.2 (31.2) |

79.0 (26.1) |

73.7 (23.2) |

98.7 (37.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.9 (12.7) |

59.9 (15.5) |

68.1 (20.1) |

75.0 (23.9) |

82.3 (27.9) |

88.5 (31.4) |

90.9 (32.7) |

90.7 (32.6) |

86.4 (30.2) |

76.9 (24.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

57.7 (14.3) |

74.8 (23.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.1 (6.7) |

48.2 (9.0) |

55.7 (13.2) |

62.5 (16.9) |

70.4 (21.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

81.1 (27.3) |

80.1 (26.7) |

75.0 (23.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

46.8 (8.2) |

63.3 (17.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.2 (0.7) |

36.5 (2.5) |

43.3 (6.3) |

50.0 (10.0) |

58.5 (14.7) |

67.0 (19.4) |

71.2 (21.8) |

69.5 (20.8) |

63.7 (17.6) |

52.1 (11.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

36.0 (2.2) |

51.9 (11.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.6 (−8.6) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

34.2 (1.2) |

43.2 (6.2) |

56.4 (13.6) |

64.6 (18.1) |

61.0 (16.1) |

49.6 (9.8) |

34.5 (1.4) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

13.7 (−10.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

6 (−14) |

12 (−11) |

24 (−4) |

34 (1) |

43 (6) |

56 (13) |

52 (11) |

38 (3) |

25 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

−2 (−19) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.81 (148) |

5.52 (140) |

5.04 (128) |

5.57 (141) |

4.40 (112) |

4.23 (107) |

4.05 (103) |

4.15 (105) |

3.42 (87) |

3.48 (88) |

4.24 (108) |

5.20 (132) |

55.11 (1,399) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.6 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 9.0 | 96.6 |

| Source: NOAA[29][30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics edit

Aliceville edit

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 640 | — | |

| 1920 | 944 | 47.5% | |

| 1930 | 1,066 | 12.9% | |

| 1940 | 1,475 | 38.4% | |

| 1950 | 3,170 | 114.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,194 | 0.8% | |

| 1970 | 2,851 | −10.7% | |

| 1980 | 3,207 | 12.5% | |

| 1990 | 3,009 | −6.2% | |

| 2000 | 2,567 | −14.7% | |

| 2010 | 2,486 | −3.2% | |

| 2020 | 2,177 | −12.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

Aliceville first appeared on the 1910 U.S. Census as an incorporated town.[32] It became the largest town in Pickens County in 1930,[33] surpassing Reform, and continues to hold the title as of 2010.[34]

2020 census edit

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 425 | 19.52% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 1,679 | 77.12% |

| Asian | 6 | 0.28% |

| Other/Mixed | 41 | 1.88% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 26 | 1.19% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 2,177 people, 898 households, and 625 families residing in the city.

2010 Census data edit

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 2,486 people living in the city. 74.9% were African American, 22.6% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.0% Asian, 0.8% from some other race and 1.6% of two or more races. 1.2% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

2000 Census data edit

As of the census[36] of 2000, there were 2,567 people, 978 households, and 646 families living in the city. The population density was 570.9 inhabitants per square mile (220.4/km2). There were 1,092 housing units at an average density of 242.9 per square mile (93.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 32.29% White, 66.54% Black or African American, 0.12% Native American, 0.31% Asian, and 0.74% from two or more races. 0.39% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 978 households, out of which 32.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.2% were married couples living together, 28.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.9% were non-families. 32.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.51 and the average family size was 3.20.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 30.2% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 21.4% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 19.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 75.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 64.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $17,092, and the median income for a family was $23,233. Males had a median income of $25,114 versus $15,952 for females. The per capita income for the city was $11,028. About 38.7% of families and 44.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 64.6% of those under age 18 and 29.9% of those age 65 or over.

Aliceville Precinct/Division (1930-) edit

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 3,154 | — | |

| 1940 | 4,798 | 52.1% | |

| 1950 | 6,221 | 29.7% | |

| 1960 | 6,664 | 7.1% | |

| 1970 | 5,739 | −13.9% | |

| 1980 | 5,456 | −4.9% | |

| 1990 | 5,373 | −1.5% | |

| 2000 | 6,156 | 14.6% | |

| 2010 | 5,384 | −12.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

The Aliceville Precinct (Pickens County Precinct 19) first appeared on the 1930 U.S. Census.[37] Prior to that, from 1880 to 1920, it had been known as the Franconia Precinct.[38] In 1960, Aliceville precinct was changed to a census division as part of a general reorganization of counties.[39] In 2000, it was merged with the Raleigh Census Division and renamed South Pickens Division.[40] In 2010, the name was changed back to Aliceville Census Division.[34]

Economy edit

Aliceville is home to the Federal Correctional Institution, Aliceville. Construction on the $250 million, 1,500-bed medium-security women's prison began in 2008 and was completed in 2011. The facility also includes a 256-bed minimum-security work camp.

Arts and culture edit

Aliceville is home to the Aliceville POW Museum, which houses papers, letters, documents, maps, and other material from the World War II prisoner of war camp situated in the city from 1942 to 1945.[15] The museum opened in 1995 and, in addition to the POW material, houses a permanent exhibit on the Aliceville Coca-Cola bottling plant.[41]

Education edit

- Aliceville High School

- Aliceville Middle School

- Aliceville Elementary School

Notable people edit

- Stephen Fleck, medical officer at Camp Aliceville[42]

- Butch Hobson, major league third baseman and manager[43]

- Amos Jones, American football coach

- Walter Jones, former offensive tackle for the Seattle Seahawks[44]

- Simmie Knox, portrait artist[45]

- Henry Smith, former NFL defensive tackle

Photo Gallery edit

-

Roadsigns at Aliceville

-

George Downer Airport, Aliceville

-

Federal Correctional Institution, Aliceville

-

Dr. William Hughes Plantation, 1937 (near Aliceville)

-

Dr. William Hughes Plantation, 1937 (near Aliceville)

-

Interior Stairway, Dr. William Hughes Plantation, 1937 (near Aliceville)

-

Dr. William Hughes Plantation, 1937 (near Aliceville)

-

Ingleside House, 1937, Aliceville

See also edit

Further reading edit

- Ruth Beaumont Cook (2007). Guests Behind the Barbed Wire: German POWs in America: A True Story Of Hope And Friendship. Crane Hill Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57587-260-5. - A history of Camp Aliceville which "highlights the human dimension of war and captivity, and shows the various ways in which the small community of Aliceville became connected to events and places in the United States and abroad."[46]

Notes edit

- ^α "The onlooker," but literally "the fence-guest."

References edit

Notes edit

References edit

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Aliceville". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ 1830-2010 U.S. Censuses research on Pickens County, Alabama communities

- ^ "Aliceville is in Most Fertile Part of Pickens County What Was Once a Swamp Has Now Become a Thriving Little City". Montgomery Advertiser. April 27, 1916. p. 7.

- ^ Will T. Sheehan (September 18, 1905). "The Story of Aliceville Only Two Years of Age". Montgomery Advertiser. p. 5.

- ^ "To Boom Aliceville Company is Organized for That Purpose". Montgomery Advertiser. June 2, 1905. p. 2.

- ^ "To Incorporate Aliceville. Extension of Railroad to Farfield is Progressing". Montgomery Advertiser. February 2, 1907. p. 2.

- ^ "Aliceville Election. West Alabama Magie Town Selects its First Officers". Montgomery Advertiser. March 20, 1907. p. 8.

- ^ a b c "Excitement at Aliceville: Mounted Negroes Fired on and One is Hurt". Montgomery Advertiser. September 1, 1907. p. 6.

- ^ a b "Progress of Aliceville. Street and Sidewalks Are Being Improved". Montgomery Advertiser. March 2, 1908. p. 8.

- ^ "News of Aliceville Work of Street Paving in Completed". Montgomery Advertiser. June 7, 1910. p. 8.

- ^ a b c Cronenberg, Allen (2003). Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II. University of Alabama Press. pp. 95–103. ISBN 0817307370.

world war two prison alabama.

- ^ a b Rufus Ward (2012). Columbus Chronicles: Tales from East Mississippi. The History Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-60949-859-7.

- ^ Arnold Krammer (2008). Prisoners of War: A Reference Handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-275-99300-9.

- ^ a b "Aliceville". The Tuscaloosa News. July 11, 1993.

- ^ a b c d Samuel S. Hill (1983). On Jordan's Stormy Banks: Religion in the South : a Southern Exposure Profile. Mercer University Press. pp. 23–5. ISBN 978-0-86554-035-4.

- ^ James T. Wooten (September 5, 1969). "Wallace Backed on School Stand: Alabama Legislature Urges Defiance of Integration—Classes Begin Calmly". New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ "Troops at Alabama Schools". New York Times. p. 16.

- ^ a b Marsha Darling (February 24, 2014). Enforcing and Challenging the Voting Rights Act: Race, Voting, and Redistricting. Taylor & Francis. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-135-73045-1.

- ^ Lani Guinier (March 7, 2003). Lift Every Voice: Turning a Civil Rights Setback Into a New Vision of Social Justice. Simon and Schuster. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7432-5351-2.

- ^ Art Harris (February 6, 1982). "Pickens County Flare-Up: The Story of 2 Blacks Found Guilty". Washington Post. p. A6.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c Reginald Stuart (February 7, 1982). "March Is Begun in Alabama To Back Voting Rights Law". New York Times. p. 24.

- ^ "Justice Dept. to Send Poll-Watchers to South". New York Times. July 31, 1984. p. A14.

- ^ Betsy Morris; Cameron McWhirter (November 9, 2013). "Crude Oil Train Derails; Explodes". Wall Street Journal.(subscription required)

- ^ Reeves, Jay (March 15, 2014). "Oil mars Ala. swamp months after crude train crash". Missoulian. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ^ Robbins, Michael W (May 27, 2014). "Why Do These Tank Cars Carrying Oil Keep Blowing Up?". Mother Jones. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Aliceville, Alabama Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access - Station: Aliceville, AL". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access - Station: Aliceville L&D, AL". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Supplement for Alabama - Population, Agriculture, Manufactures, Mines and Quarries" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1910.

- ^ "Alabama - Composition and Characteristics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1930. pp. 81–140.

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau (December 2012). "Alabama: 2010 Census of Population and Housing - Summary Population and Housing Characteristics" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 2, 2019.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Population - United States Summary" (PDF). 1930. p. 47.

- ^ "Table III - Population of Civil Divisions less than counties, in the aggregate at the Censuses of 1880 and 1870" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1870.

- ^ "Number of Inhabitants - Alabama" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1960.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (June 2002). "Alabama: 2000 Census of Population and Housing - Summary Population and Housing Characteristics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2019.

- ^ "History". cityofaliceville.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. (archived from the original on December 14, 2007)

- ^ S. Fleck; J.W. Kellam, J. W.; A.J. Klippen, A. J. (March 1944). "Diphtheria Among German Prisoners of War". Bull. U. S. Army M (74): 80–89.

- ^ Jim Murray (March 17, 1981). "It Really Was Hobson's Choice". Los Angeles Times. p. D1.

- ^ Mark Stewart (July 1, 2008). The Seattle Seahawks. Norwood House Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-59953-201-1.

- ^ Jessie Carney Smith (December 1, 2012). Black Firsts: 4,000 Ground-Breaking and Pioneering Historical Events. Visible Ink Press. p. 2004. ISBN 978-1-57859-425-2.

- ^ Matthias Reiss (2007). "Guests Behind the Barbed Wire: German POWs in America; A True Story of Hope and Friendship (review)". The Alabama Review. 60 (4).(subscription required)

External links edit

- Archived version of Camp Alice POW Museum Official Website

- Library of Congress record for Der Zaungast, Camp Alice prisoner newsletter

33°07′35″N 88°09′16″W / 33.126276°N 88.154427°W