Summary

Allkaruen (meaning "ancient brain") is a genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur from the Early Jurassic Cañadon Asfalto Formation in Argentina.[2] It contains a single species, Allkaruen koi.

| Allkaruen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal elements | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Clade: | †Macronychoptera |

| Clade: | †Novialoidea |

| Clade: | †Breviquartossa |

| Clade: | †Pterodactylomorpha |

| Genus: | †Allkaruen Codorniú et al. 2016[2] |

| Species: | †A. koi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Allkaruen koi Codorniú et al. 2016[2]

| |

Description edit

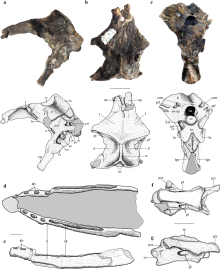

As demonstrated by a CT scan, the braincase of Allkaruen exhibits a unique set of traits that are intermediate between more basal pterosaurs such as Rhamphorhynchus and more derived pterodactyloid pterosaurs such as Anhanguera. These traits are the position of the anterior semicircular canal of the inner ear,[3] the relative orientations of the occiput and occipital condyle, the relative positions of the lateral margins of the flocculus and cerebral hemispheres, and the ratio between the length of the brain and the height of the hindbrain.[2] In addition, the relative orientations of the frontal bone and lateral semicircular canal are more similar to Rhamphorhynchus than Anhanguera, while the optic lobes are positioned lower than the forebrain as in pterodactyloids.[2][3] This unique combination of characters indicates that the anatomy of the braincase in pterodactyloids evolved through mosaic evolution.

The parietals of Allkaruen were long, being 60% of the length of the frontals; the frontals themselves were broad, flat, and extensively pneumatized. The lower jaw was about 3.5 times the length of the section of the skull that is preserved, and it is curved upwards at its tip. The dentary bore four or five tooth sockets in its front half, and in the latter half they were replaced by a groove; this combination is unique among pterosaurs.[2]

Allkaruen was a small pterosaur. The holotype specimen would have been an adult, since its skull was entirely fused.[2]

Discovery and naming edit

The holotype of Allkauren consists of a braincase (MPEF-PV 3613), a mandible (MPEF-PV 3609), and a cervical vertebra (MPEF-PV 3615); a similar cervical vertebra (MPEF-PV 3616) was also referred to the genus.[2] These elements were in 2000 discovered in the Cañadón Asfalto Formation, Cerro Cóndor, Chubut, Argentina, which has been dated to the Middle-Late Toarcian, 179.17 ± 0.12-178.07 ± 0.21 m.a (although earlier estimates have suggested an earliest-Bathonian age).[4][5] Other elements, mostly disarticulated and consisting of a number of limb bones as well as another mandible, were also discovered at the site.[2][6]

The name Allkaruen is Tehuelche in origin, being derived from all ("brain") and karuen ("ancient"). The specific name, koi, originates from the Tehuelche word for "lake", in reference to the fact that the type locality would have been a saline lake.[2][7]

Classification edit

In 2016, two phylogenetic analyses were conducted based on the dataset from the description of Darwinopterus in order to determine the phylogenetic position of Allkaruen.[8] One analysis was restricted to the holotype braincase, while the other included the holotype mandible and cervical vertebrae as well. Allkaruen was consistently recovered as the sister taxon of the Monofenestrata; the consensus of the 360 most parsimonious trees is shown below.[2]

In their 2024 description of Ceoptera, Martin-Silverstone et al. found reasonable evidence in their phylogenetic analyses that Allkaruen instead represents the earliest known member of the Darwinoptera within Monofenestrata. They further redefined the clade Darwinoptera as comprising all taxa more closely related to the clade containing Allkaruen koi and Cuspicephalus scarfi than to Quetzalcoatlus. Their results are shown in the cladogram below:[9]

| Monofenestrata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

References edit

- ^ Fantasia, A.; Föllmi, K. B.; Adatte, T.; Spangenberg, J. E.; Schoene, B.; Barker, R. T.; Scasso, R. A. (2021). "Late Toarcian continental palaeoenvironmental conditions: An example from the Canadon Asfalto Formation in southern Argentina". Gondwana Research. 89 (1): 47–65. Bibcode:2021GondR..89...47F. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2020.10.001. S2CID 225120452. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Codorniú, L.; Carabajal, A.P.; Pol, D.; Unwin, D.; Rauhut, O.W.M (2016). "A Jurassic pterosaur from Patagonia and the origin of the pterodactyloid neurocranium". PeerJ. 4: e2311. doi:10.7717/peerj.2311. PMC 5012331. PMID 27635315.

- ^ a b Witmer, L.M.; Chatterjee, S.; Franzosa, J.; Rowe, T. (2003). "Neuroanatomy of flying reptiles and implications for flight, posture and behaviour" (PDF). Nature. 425 (6961): 950–953. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..950W. doi:10.1038/nature02048. PMID 14586467. S2CID 4431861.

- ^ Pol, D.; Gomez, K.; Holwerda, F. M.; Rauhut, O. W.; Carballido, J. L. (2022). "Sauropods from the Early Jurassic of South America and the Radiation of Eusauropoda". South American Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. 1 (1): 131–163. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-95959-3_4. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Cúneoa, R.; Ramezani, J.; Scasso, R.; Pol, D.; Escapa, I.; Zavattieri, A.M.; Bowring, S.A. (2013). "High-precision U–Pb geochronology and a new chronostratigraphy for the Cañadón Asfalto Basin, Chubut, central Patagonia: Implications for terrestrial faunal and floral evolution in Jurassic". Gondwana Research. 24 (3–4): 1267–1275. Bibcode:2013GondR..24.1267C. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.01.010. hdl:11336/78351.

- ^ Codorniú, L.; Rauhut, O.W.M.; Pol, D. (2010). "Osteological features of Middle Jurassic pterosaurs from Patagonia (Argentina)". Acta Geoscientica Sinica. 31 (suppl. 1): 12–13.

- ^ Cabaleri, N.G.; Armella, C.; Silva Nieto, D.G. (2005). "Saline paleolake of the Cañadón Asfalto Formation (Middle-Upper Jurassic), Cerro Cóndor, Chubut province (Patagonia), Argentina". Facies. 51 (1): 350–364. Bibcode:2005Faci...51..350C. doi:10.1007/s10347-004-0042-5. S2CID 129090656.

- ^ Lu, J.; Unwin, D.M.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Q. (2010) [2009]. "Evidence for modular evolution in a long-tailed pterosaur with a pterodactyloid skull". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1680): 383–389. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1603. PMC 2842655. PMID 19828548.

- ^ Martin-Silverstone, Elizabeth; Unwin, David M.; Cuff, Andrew R.; Brown, Emily E.; Allington-Jones, Lu; Barrett, Paul M. (2024-02-05). "A new pterosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Skye, Scotland and the early diversification of flying reptile". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. doi:10.1080/02724634.2023.2298741. ISSN 0272-4634.