Summary

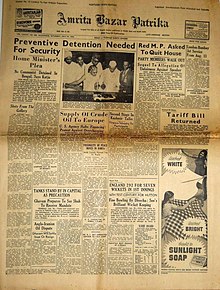

Amrita Bazar Patrika was one of the oldest daily newspapers in India. Originally published in Bengali script,[3] it evolved into an English format published from Kolkata and other locations such as Cuttack, Ranchi and Allahabad.[4] The paper discontinued its publication in 1991 after 123 years of publication.[1][3] Its sister newspaper was the Bengali-language daily newspaper Jugantar, which remained in circulation from 1937 till 1991.[2][1]

| |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Founder(s) | Sisir Kumar Ghose and Moti Lal Ghosh |

| Founded | 20 February 1868 |

| Language | Bengali and English (bilingual) |

| Ceased publication | 1991 |

| Circulation | 25,000 (before 1991)[1] |

| Sister newspapers | Jugantar[2] |

It debuted on 20 February 1868. It was started by Sisir Ghosh and Moti Lal Ghosh, sons of Hari Naryan Ghosh, a rich merchant from Magura, in District Jessore, in Bengal Province of British Empire in India. The family had constructed a Bazaar and named it after Amritamoyee, wife of Hari Naryan Ghosh. Sisir Ghosh and Moti Lal Ghosh started Amrita Bazar Patrika as a weekly first. It was first edited by Motilal Ghosh, who did not have a formal university education. It had built its readership as a rival to Bengalee which was being looked after by Surendranath Banerjee.[5] After Sisir Ghosh retired, his son Tushar Kanti Ghosh became editor for the next sixty years, running the newspaper from 1931 to 1991.[6]

History edit

Amrita Bazaar Patrika was the oldest Indian-owned English daily. It played a major role in the evolution and growth of Indian journalism and made a striking contribution to creating and nurturing the Indian freedom struggle. In 1920, Russian Communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin described ABP as the best nationalist paper in India.[citation needed]

ABP was born as a Bengali weekly in February 1868 in the village of Amrita Bazaar in Jessore district (now in Bangladesh). It was started by the Ghosh brothers to fight the cause of peasants who were being exploited by indigo planters. Sisir Kumar Ghosh was the first editor. The Patrika operated out of a battered wooden press purchased for Rs 32.

In 1871, the Patrika moved to Calcutta (now Kolkata), due to the outbreak of plague in Amrita Bazaar. Here it functioned as a bilingual weekly, publishing news and views in English and Bengali. Its anti-government views and vast influence among the people was a thorn in the flesh of the government. Lord Lytton, the Viceroy of India promulgated the Vernacular Press Act on 1878 mainly against ABP.

The Patrika became a daily in 1891. It was the first Indian-owned English daily to go into investigative journalism. During the tenure of Lord Lansdowne, a Patrika journalist rummaged through the waste paper basket of the Viceroy's office and pieced together a torn up letter detailing the Viceroy's plans to annex Kashmir. ABP published the letter on its front page, where it was read by the Maharaja of Kashmir, who immediately went to London and lobbied for his independence.[7]

Sisir Kumar Ghosh also launched vigorous campaigns against restrictions on civil liberties and economic exploitation. He wanted Indians to be given important posts in the administration. Both he and his brother Motilal were deeply attached to Bal Gangadhar Tilak. When Tilak was prosecuted for sedition in 1897, they raised funds in Calcutta for his defence. They also published a scathing editorial against the judge who sentenced Tilak to 6 years of imprisonment, for 'presuming to teach true patriotism to a proved and unparalleled patriot.'

The Patrika had many brushes with Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India at the time of the Partition of Bengal (1905). It referred to him as 'Young and a little foppish, and without previous training but invested with unlimited powers.' Because of such editorials, the Press Act of 1910 was passed and a security of Rs 5,000 was demanded from ABP. Motilal Ghosh was also charged with sedition but his eloquence won the case.

After this, the Patrika started prefacing articles criticising the British government with ridiculously exuberant professions of loyalty to the British crown. When Subhas Chandra Bose and other students were expelled from Calcutta Presidency College, the Patrika took up their case and succeeded in having them re-admitted.[citation needed]

Even after Motilal Ghosh's death in 1922, the Patrika kept up its nationalist spirit. Higher securities of Rs 10,000 were demanded from it during the Salt Satyagraha. Its editor Tushar Kanti Ghosh (son of Sisir Kumar Ghosh) was imprisoned. The Patrika contributed its share to the success of its freedom movement under the leadership of Gandhi and suffered for its views and actions at the hands of the British rulers.[citation needed]

The Patrika espoused the cause of communal harmony during the Partition of India. During the great Calcutta killings of 1946, the Patrika left its editorial columns blank for three days. When freedom dawned on 15 August 1947, the Patrika published in an editorial:

It is dawn, cloudy though it is. Presently sunshine will break.[citation needed]

Archives edit

As a part of the 'Endangered Archive project' attempting to rescue text published prior to 1950, the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta took up the project of digitizing the old newspapers (ABP and Jugantar) for safe storage and retrieval in 2010.[8] The newspaper archives are also available from the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library, Delhi, and in 2011 over one lakh images from the newspaper were digitized by the library and available online.[9] and also at The Centre of South Asian Studies at the University of Cambridge.

References edit

- ^ a b c Banerjee, Ruben (15 July 1991). "Debts kill 123-year-old English daily Amrita Bazar Patrika". India Today. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b Misra, Shubhangi (14 August 2021). "Amrita Bazar Patrika — fiery newspaper took on British but then came a tame turn, and tragedy". The Print. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b Gupta, Subhrangshu (2 January 2003). "Amrita Bazar Patrika may be relaunched". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- ^ Registrar of Newspapers for India Archived 13 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Political Agitators in India, A Confidential Report, pp. 15, Available in Digitized form on Archives.org, contributed by Library of University of Toronto, Digitized for Microsoft Corporation by Internet Archive in 2007, provided by University of Toronto, accessed on 8 June 2009 and link at https://archive.org/details/politicalagitato00slsnuoft

- ^ "Tushar Kanti Ghosh, Independence Crusader, Dies at 96". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ^ Tharoor, Shashi (2017). Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-84904-808-8.

- ^ Retrieval of two major and endangered newspapers : CSSSC Archived 6 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nehru Memorial library digitised". The Times of India. 28 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012.

External links edit

- Endangered Archive Project, CSSSC

- Nehru Memorial Museum & Library

- Centre of South Asian Studies