Summary

The Artistic Patronage of the Neapolitan Angevin dynasty includes the creation of sculpture, architecture and paintings during the reigns of Charles I, Charles II and Robert of Anjou in the south of Italy.

In 1266, Charles of Anjou established the Neapolitan Angevin dynasty, a royal dynasty that ruled Naples until 1435. Upon taking the crown, Charles of Anjou (now Charles I) hoped to solidify his rule by commissioning great works of art for public display. Recognizing art's potential as a political tool, Charles invited artists from France and Italy to join him at his court in Naples. Subsequent kings of Naples would also employ art as a means of validating their dynastic claims. This forged a tradition of artistic patronage in which the Royal Court of Naples functioned as an important artistic center, drawing artists and architects from throughout France and Italy. From their impressive artistic and architectural programs, emerged a Neapolitan variation of the French Gothic style that became increasingly dominated by Italian artistic developments.[1] Artists such as Arnolfo di Cambio, Pietro Cavallini, and Simone Martini created works for the Angevin kings of Naples, contributing to the kingdom's wealth of artistic riches.

Charles I of Anjou edit

Sculpture edit

Tuscan sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio entered the service of Charles I in 1277. Prior to arriving in Rome, Arnolfo di Cambio had worked on the pulpit for the Siena Cathedral as part of the workshop of Nicola Pisano, which was completed in 1268. Arnolfo di Cambio completed a marble statue of the Charles I now housed in the Musei Capitolini. One of the first portrait statues since antiquity, the statue of Charles I helped set the precedent for royal portrait sculpture in the Renaissance.[2] While the exact location of its original placement is not known, it would be fair to assume that it stood in a monumental setting where it could be admired by the King's subjects.[3] The sculpture shows the king sitting stoically with a royal scepter in his right hand and a jeweled crown upon his head. In addition to this medieval iconography, however, King Charles's royal robes and lion headed curule seat have been borrowed from Roman sculpture.[4] Arnolfo di Cambio portrayed this medieval Neapolitan King as an authoritative Roman Emperor, but has also succeeded in maintaining the individual likeness of his royal patron.

Architecture edit

As the founder of a new royal dynasty, Charles I needed to build a royal residence that could function as the seat of his government. He commissioned architect Pietro de Caulis to design the Castel Nuovo (1279–87), which was to serve as the residence of the kings and queens of Naples.[5] Charles I provided funding for the rebuilding of the Franciscan church of San Lorenzo Maggiore, an early example of the Neapolitan adaptation of the French Gothic style.[6] While the tracery designs at San Lorenzo Maggiore were inspired by the French Gothic church of Saint Denis, its “cavernous nave and its unarticulated walls” show the influence of Italian Franciscan churches.[7]

Charles II of Anjou edit

Architecture edit

During the reign of Charles II of Anjou (1285-1308), the second Angevin King of Naples, the king's wife, Mary of Hungary, Queen of Naples, was responsible for initiating a number of architectural projects. The most important of these projects was the rebuilding of the Clarissan convent of Santa Maria Donna Regina Vecchia, after an earthquake destroyed the original convent in 1293. In 1307, Queen Mary donated funds to the abbess of the Clarissans for the construction of the new church. The Clarissans, or Poor Clares, were the female branch of the Franciscan Order, founded by Saint Clare of Assisi. The church comprises two levels; on the ground level is a dark, low-vaulted nave and above it is a choir supported on eight columns.[8] The ground level was most likely for the congregation and the upper level reserved for the nuns.[9] A polygonal apse with stained glass lancet windows illuminates the church, contrasting with the dark nave below.[9] By commissioning Santa Maria Donna Regina, Mary of Hungary began a tradition of royal female patronage in the Kingdom of Naples.[7]

In 1283, Charles II funded the reconstruction of the Dominican church of San Domenico Maggiore, a church similar to his father's church of San Lorenzo Maggiore in its fusion of French Gothic and Italian stylistic elements.[10]

Painting edit

In 1308, Roman painter Pietro Cavallini and a group of his pupils arrived at the royal court Naples. Cavallini and his students are believed to have been commissioned by Mary of Hungary to paint the fresco cycles located above the choir in the church of Santa Maria Donna Regina.[11] The fresco cycles, completed between 1320 and 1323, cover all four of the church walls and include: the Last judgment on the west wall; pairs of prophets and apostles and the lives of Saint Agnes and Saint Catherine on the south wall; pairs of prophets and apostles, the life of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, and the Passion of Christ on the north wall; an “angelic hierarchy” on the east wall.[12] In 1308, Charles II commissioned Pietro Cavallini to paint a fresco cycle depicting three scenes from the life of Mary Magdalene in the Brancaccio chapel at the Dominican church of San Domenico Maggiore. The painter Giotto worked at the royal court of Naples from 1328 until 1332, during which time he painted a number of panel paintings and frescoes. All of these works are unfortunately lost, but a work by one of his followers survives in the Brancaccio Chapel at the church of San Domenico Maggiore, a fresco of Noli Me Tangere from around 1310.[13]

Robert of Anjou edit

Painting edit

Robert of Anjou was the third son of King Charles II and Mary of Hungary. Charles II's first son Charles Martel of Anjou had died by 1295, putting his second son Louis next in line for the throne. Louis, however, did not desire the crown of Naples, and would instead become bishop of the diocese of Toulouse in 1296. Louis and Charles II died in 1297 and in 1308 respectively, leading to Robert's coronation in 1309. By 1317, Louis, with the help of Robert's royal influence, was canonized as Saint Louis of Toulouse. The Neapolitan House of Anjou now possessed its own saint, which Robert of Anjou would use to his political advantage.[14] It was around this year that the Sienese painter Simone Martini was commissioned, most likely by Robert of Anjou, to paint the Altarpiece of St Louis of Toulouse, now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte.[15] In this altarpiece, Saint Louis of Toulouse sits enthroned in his brown sackcloth and crimson jeweled cope, holding his crozier with his right hand and donning his bishop's mitre on his haloed head.[15][16] Two angels hover over him, sustaining the crown of sainthood above his mitre.[17] As he receives the celestial crown, the Saint, with his left hand, offers the Neapolitan crown to his brother Robert of Anjou, shown in profile, who kneels before him.[17]

Despite the presence of religious iconography, the altarpiece's motives were more political than devotional.[18] Robert of Anjou's nephew Caroberto, as the son of Charles II's first son Charles Martel, had a legitimate claim to the Neapolitan throne. Robert of Anjou sought to validate his royal ascension through Simone Martini's employment of both dynastic and religious iconography.[19] Iconographic parallels can be identified between Simone Martini's figure of Saint Louis of Toulouse and Arnolfo di Cambio's figure of Charles of Anjou.[20] Both figures are shown frontally and are seated on lion-shaped thrones; they wield objects of power and wear jeweled crowns.[21] Saint Louis is represented more like a great king than a Franciscan saint, emphasizing the altarpiece's political function.[22]

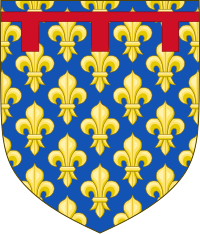

Much of the altarpiece's dynastic political power was derived from its decorative iconography. The most prominent dynastic icon featured in the altarpiece is the fleur-de-lys, the symbol of the French monarchy. The Angevins of Naples had descended from the French House of Capet and thus utilized the fleur-de-lys as their royal emblem. The fleur-de-lys motif is punched into the traditional Sienese gold ground, forming a decorative border around Simone Martini's main panel.[23] The frame of the altarpiece is painted a deep blue and decorated with large gold fleurs-de-lys, modelled in deep relief.[23] Below the frame is a predella in which Simone Martini painted five scenes from the life of Saint Louis of Toulouse. This would have proved challenging for Simone as Saint Louis had just been canonized, requiring him to invent a new set of iconography.[24] These scenes function as both religious and dynastic icons by depicting the miracles of a saint from the Angevin dynasty.[25] Two additional dynastic icons can be observed on the clasp of St Louis's cope: the red and yellow heraldic colors of Provence and the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[26] By presenting these two territories, both claimed by the Angevins, Simone has revealed the extent of Robert of Anjou's political reach.[26]

Architecture edit

Robert of Anjou and his wife Sancha of Majorca financed the construction of the Franciscan double convent of Santa Chiara (Naples). The monastic complex was begun in around 1310 by the architect Gagliardo Primario and was completed by the 1340s. The structure included two cloisters to separately house the Poor Clares and the Franciscan friars.[27] The main church comprised a long nave with nine lateral chapels on each side and a friars’ choir at the far end by the main altar.[28] A wall stood behind the friars’ choir, separating it from the nuns’ choir located on the other side.[29] A long gallery, supported by the lateral chapels, stretched across the length of the church, above which was a row of clerestory windows.[30] The design of Santa Chiara alludes to the cathedrals of Provence and Catalonia.[31] Santa Chiara's monumental scale surpassed that of all churches in the kingdom, turning this Franciscan convent into a display of Angevin royal power.[32]

Sculpture edit

In order to further solidify his dynastic claims, Robert of Anjou initiated an ambitious campaign to erect funerary monuments for members of the Angevin dynasty. The tomb's structure inside of Santa Chiara was designed by architect Gagliardo Primario and the individual funerary monuments were erected by a number of different sculptors. Robert commissioned the Sienese sculptor Tino di Camaino to create the funerary monument for his mother, Mary of Hungary. Tino di Camaino had arrived at the royal court of Naples in 1323 and worked for the Angevins for the last fourteen years of his life. Unlike the other funerary monuments commissioned by Robert, which were to be erected inside of the monastic complex of Santa Chiara, Mary of Hungary was to be placed inside of Santa Maria Donna Regina. Tino's sculptural monument for Mary consisted of a sarcophagus decorated with seven niches, each one containing a sculpted figure of one of her seven sons.[26] Featured most prominently in the central niche is St. Louis of Toulouse.[26] Robert sits to his right, affirming the king's celestial ties. In this representation of Robert, as in Simone Martini's painting, his dynastic legitimacy is emphasized. He sits majestically, wearing a crown and holding symbols of royal power. The chest of Mary's tomb is adorned with figures depicting the four cardinal virtues: Prudentia, Temperantia. Justitia, and Fortitudo.[33]

Robert of Anjou's tomb was created by Florentine sculptors Pacio and Giovanni Bertini, who had most likely trained with Tino di Camaino.[34] For his monument, erected inside of Santa Chiara, Pacio and Giovanni Bertini represented Robert of Anjou in a relief at the center of the sarcophagus, in a recumbent effigy on the sarcophagus, and in a free-standing sculpture.[35] In the free-standing sculpture, Robert is portrayed as an enthroned Roman ruler, much like in Arnolfo di Cambio's statue of his grandfather, Charles I.[36] In the recumbent effigy, however, Robert is barefoot and wearing a friar's tunic, showing his devotion to the Franciscan order.[37] In the relief at the center of the sarcophagus, Robert is depicted with members of his royal family, including his successor, his granddaughter Joan I of Naples.[38] With this funerary monument, Pacio and Giovanni Bertini successfully present an image of both royal and spiritual power, and secure the dynastic claims of future Angevins rulers.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ John T. Paoletti and Gary M. Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 3rd ed. (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2005), 128.

- ^ Jill Elizabeth Blondin, “Pope Sixtus IV at Assisi: The Promotion of Papal Power,” in Patronage and Dynasty: The Rise of the Della Rovere in Renaissance Italy, ed. Ian Verstegen (Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press, 2007), 30.

- ^ Paul Williamson, Gothic Sculpture, 1140-1300 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), 252.

- ^ Arthur Lincoln Frothingham, The monuments of Christian Rome from Constantine to the Renaissance (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1908), 240.

- ^ Janis Elliott and Cordelia Warr, “Introduction,” in The Church of Santa Maria Donna Regina: Art, Iconography, and Patronage in Fourteenth Century Naples, ed. Janis Elliott and Cordelia Warr (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2004), 1.

- ^ Elliott and Warr, “Introduction,” in Elliott and Warr, The Church of Santa Maria Donna Regina, 1.

- ^ a b Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 128.

- ^ Cathleen A. Fleck, “’Blessed the Eyes that See Those Things you See’: The Trecento Choir Frescoes at Santa Maria Donnaregina in Naples,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 67, no. 2 (2004): 204.

- ^ a b Fleck, “ 'Blessed the Eyes that See Those Things you See,’” 204

- ^ Elliott and Warr, “Introduction,” in Elliott and Warr, The Church of Santa Maria Donna Regina, 1.

- ^ Samantha Kelly, “Religious patronage and royal propaganda in Angevin Naples: Santa Maria Donna Regina in context,” in Elliott and Warr, The Church of Santa Maria Donna Regina, 27.

- ^ Fleck, “’Blessed the Eyes that See Those Things you See,’” 204.

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 129-30.

- ^ Julian Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse, Robert of Anjou and Simone Martini,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 39, no. 1 (1976): 19.

- ^ a b Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 19.

- ^ Timothy Hyman, Sienese Painting (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 49.

- ^ a b Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 22.

- ^ Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 20.

- ^ Suzette Denise Scotti, “Simone Martini’s St. Louis of Toulouse and its Cultural Context” (master’s thesis, Louisiana State University, 2009), 37.

- ^ Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 24.

- ^ Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 24.

- ^ Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 24.

- ^ a b Hyman, Sienese Art, 50.

- ^ Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 30.

- ^ Gardner, “Saint Louis of Toulouse,” 30.

- ^ a b c d Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 132

- ^ Caroline Astrid Bruzelius, The Stones of Naples: Church building in Angevin Italy, 1266-1343 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 142.

- ^ Bruzelius, The Stones of Naples, 143.

- ^ Bruzelius, The Stones of Naples, 143.

- ^ Bruzelius, The Stones of Naples, 144.

- ^ Bruzelius, The Stones of Naples, 144.

- ^ Bruzelius, The Stones of Naples, 133-34.

- ^ Margaret Schaus, ed., Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia (New York: Routledge, 2006), 535.

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 133

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 133

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 134

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 134

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 134

Bibliography edit

- Blondin, Jill Elizabeth. Pope Sixtus IV at Assisi: The Promotion of Papal Power. In Patronage and Dynasty: The Rise of the Della Rovere in Renaissance Italy, edited by Ian Verstegen, 19-36. Kirksville, Missouri: Truman State University Press, 2007.

- Bruzelius, Caroline Astird. The Stones of Naples: Church building in Angevin Italy, 1266-1343. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Elliott, Janis, and Cordelia Warr, eds. The Church of Santa Maria Donna Regina: Art, Iconography, and Patronage in Fourteenth Century Naples. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2004.

- Fleck, Cathleen A. ’Blessed the Eyes that See Those Things you See’: The Trecento Choir Frescoes at Santa Maria Donnaregina in Naples. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 67, no. 2 (2004): 201-24.

- Frothingham, Arthur Lincoln. The monuments of Christian Rome from Constantine to the Renaissance. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1908.

- Gardner, Julian. Saint Louis of Toulouse, Robert of Anjou and Simone Martini. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 39, no. 1 (1976): 12-33.

- Hyman, Timothy. Sienese Painting. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003.

- Kelly, Samantha. Religious patronage and royal propaganda in Angevin Naples: Santa Maria Donna Regina in context. In Elliott and Warr, The Church of Santa Maria Donna Regina, 27-44.

- Paoletti, John T., and Gary M. Radke. Art in Renaissance Italy. 3rd ed. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2005.

- Schaus, Margaret, ed. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Scotti, Suzette Denise. Simone Martini’s St. Louis of Toulouse and its Cultural Context. Master's thesis, Louisiana State University, 2009.

- Williamson, Paul. Gothic Sculpture, 1140-1300. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1998.