Summary

Assamese[a] or Asamiya (অসমীয়া [ɔxɔmija] ⓘ)[5] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken mainly in the north-eastern Indian state of Assam, where it is an official language. It serves as a lingua franca of the wider region[6] and has over 15 million native speakers according to Ethnologue.[1]

| Assamese | |

|---|---|

| |

| অসমীয়া | |

The word "Ôxômiya" in the Assamese alphabet | |

| Pronunciation | [ɔxɔmija] ⓘ |

| Native to | India |

| Region | |

| Ethnicity | Assamese |

Native speakers | 15 million (2011 census)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Asam Sahitya Sabha (Literary Society of Assam) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | as |

| ISO 639-2 | asm |

| ISO 639-3 | asm |

| Glottolog | assa1263 |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-w |

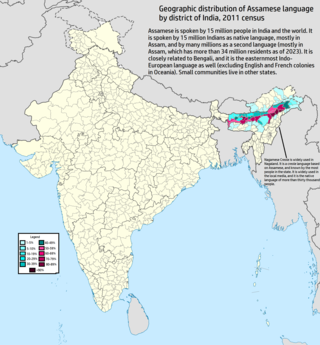

Geographic distribution of Assamese language in India | |

Nefamese, an Assamese-based pidgin in Arunachal Pradesh, was used as the lingua franca till it was replaced by Hindi; and Nagamese, an Assamese-based Creole language,[7] continues to be widely used in Nagaland. The Kamtapuri language of Rangpur division of Bangladesh and the Cooch Behar and Jalpaiguri districts of India is linguistically closer to Assamese, though the speakers identify with the Bengali culture and the literary language.[8] In the past, it was the court language of the Ahom kingdom from the 17th century.[9]

Along with other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, Assamese evolved at least before the 7th century CE[10] from the middle Indo-Aryan Magadhi Prakrit.[11] Its sister languages include Angika, Bengali, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Chakma, Chittagonian, Hajong, Rajbangsi, Maithili, Rohingya and Sylheti. It is written in the Assamese alphabet, an abugida system, from left to right, with many typographic ligatures.

History edit

Assamese originated in Old Indo-Aryan dialects, though the exact nature of its origin and growth is not clear yet.[13] It is generally believed that Assamese and the Kamatapuri lects derive from the Kamarupi dialect of Eastern Magadhi Prakrit[11] though some authors contest a close connection of Assamese with Magadhi Prakrit.[14][15] The Indo-Aryan, which appeared in the 4th–5th century in Assam,[16] was probably spoken in the new settlements of Kamarupa—in urban centers and along the Brahmaputra river—surrounded by Tibeto-Burman and Austroasiatic communities.[17] Kakati's (1941) assertion that Assamese has an Austroasiatic substrate is generally accepted—which suggests that when the Indo-Aryan centers formed in the 4th–5th centuries CE, there were substantial Austroasiatic speakers that later accepted the Indo-Aryan vernacular.[16] Based on the 7th-century Chinese traveller Xuanzang's observations, Chatterji (1926) suggests that the Indo-Aryan vernacular differentiated itself in Kamarupa before it did in Bengal,[18] and that these differences could be attributed to non-Indo-Aryan speakers adopting the language.[19][20][21] The newly differentiated vernacular, from which Assamese eventually emerged, is evident in the Prakritisms present in the Sanskrit of the Kamarupa inscriptions.[22][23]

Magadhan and Gauda-Kamarupa stages edit

The earliest forms of Assamese in literature are found in the 9th-century Buddhist verses called Charyapada[24] the language of which bear affinities with Assamese (as well as Bengali, Maithili and Odia) and which belongs to a period when the Prakrit was at the cusp of differentiating into regional languages.[25] The spirit and expressiveness of the Charyadas are today found in the folk songs called Deh-Bicarar Git.[26]

In the 12th-14th century works of Ramai Pundit (Sunya Puran), Boru Chandidas (Krishna Kirtan), Sukur Mamud (Gopichandrar Gan), Durllava Mullik (Gobindachandrar Git) and Bhavani Das (Mainamatir Gan)[27] Assamese grammatical peculiarities coexist with features from Bengali language.[28][29] Though the Gauda-Kamarupa stage is generally accepted and partially supported by recent linguistic research, it has not been fully reconstructed.[30]

Early Assamese edit

A distinctly Assamese literary form appeared first in the 13th-century in the courts of the Kamata kingdom when Hema Sarasvati composed the poem Prahrāda Carita.[31] In the 14th-century, Madhava Kandali translated the Ramayana into Assamese (Saptakanda Ramayana) in the court of Mahamanikya, a Kachari king from central Assam. Though the Assamese idiom in these works is fully individualised, some archaic forms and conjunctive particles too are found.[32][33] This period corresponds to the common stage of proto-Kamta and early Assamese.[34]

The emergence of Sankardev's Ekasarana Dharma in the 15th century triggered a revival in language and literature.[35] Sankardev produced many translated works and created new literary forms—Borgeets (songs), Ankia Naat (one-act plays)—infusing them with Brajavali idioms; and these were sustained by his followers Madhavdev and others in the 15th and subsequent centuries. In these writings the 13th/14th-century archaic forms are no longer found. Sankardev pioneered a prose-style of writing in the Ankia Naat. This was further developed by Bhattadeva who translated the Bhagavata Purana and Bhagavad Gita into Assamese prose. Bhattadev's prose was classical and restrained, with a high usage of Sanskrit forms and expressions in an Assamese syntax; and though subsequent authors tried to follow this style, it soon fell into disuse.[32] In this writing the first person future tense ending -m (korim: "will do"; kham: "will eat") is seen for the first time.[36]

Middle Assamese edit

The language moved to the court of the Ahom kingdom in the seventeenth century,[9] where it became the state language. In parallel, the proselytising Ekasarana dharma converted many Bodo-Kachari peoples and there emerged many new Assamese speakers who were speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. This period saw the emergence of different styles of secular prose in medicine, astrology, arithmetic, dance, music, besides religious biographies and the archaic prose of magical charms.[32]

Most importantly this was also when Assamese developed a standardised prose in the Buranjis—documents related to the Ahom state dealing with diplomatic writings, administrative records and general history.[32] The language of the Buranjis is nearly modern with some minor differences in grammar and with a pre-modern orthography. The Assamese plural suffixes (-bor, -hat) and the conjunctive participles (-gai: dharile-gai; -hi: pale-hi, baril-hi) become well established.[37] The Buranjis, dealing with statecraft, was also the vehicle by which Arabic and Persian elements crept into the language in abundance.[32] Due to the influence of the Ahom state the speech in eastern Assam took a homogeneous and standard form.[38] The general schwa deletion that occurs in the final position of words came into use in this period.

Modern Assamese edit

The modern period of Assamese begins with printing—the publication of the Assamese Bible in 1813 from the Serampore Mission Press. But after the British East India Company (EIC) removed the Burmese in 1826 and took complete administrative control of Assam in 1836, it filled administrative positions with people from Bengal, and introduced Bengali language in its offices, schools and courts.[39] The EIC had earlier promoted the development of Bengali to replace Persian, the language of administration in Mughal India,[40] and maintained that Assamese was a dialect of Bengali.[41]

Amidst this loss of status the American Baptist Mission (ABM) established a press in Sibsagar in 1846 leading to publications of an Assamese periodical (Orunodoi), the first Assamese grammar by Nathan Brown (1846), and the first Assamese-English dictionary by Miles Bronson (1863).[37] The ABM argued strongly with the EIC officials in an intense debate in the 1850s to reinstate Assamese.[42] Among the local personalities Anandaram Dhekial Phukan drew up an extensive catalogue of medieval Assamese literature (among other works) and pioneered the effort among the natives to reinstate Assamese in Assam.[43] Though this effort was not immediately successful the administration eventually declared Assamese the official vernacular in 1873 on the eve of Assam becoming a Chief Commissioner's Province in 1874.[44]

Standardisation edit

In the extant medieval Assamese manuscripts the orthography was not uniform. The ABM had evolved a phonemic orthography based on a contracted set of characters.[45] Working independently Hemchandra Barua provided an etymological orthography and his etymological dictionary, Hemkosh, was published posthumously. He also provided a Sanskritised approach to the language in his Asamiya Bhaxar Byakaran ("Grammar of the Assamese Language") (1859, 1873).[46] Barua's approach was adopted by the Asamiya Bhasa Unnati Sadhini Sabha (1888, "Assamese Language Development Society") that emerged in Kolkata among Assamese students led by Lakshminath Bezbaroa. The Society published a periodical Jonaki and the period of its publication, Jonaki era, saw spirited negotiations on language standardisation.[47] What emerged at the end of those negotiations was a standard close to the language of the Buranjis with the Sanskritised orthography of Hemchandra Barua.[48]

As the political and commercial center moved to Guwahati in the mid-twentieth century, of which Dispur the capital of Assam is a suburb and which is situated at the border between the western and central dialect speaking regions, standard Assamese used in media and communications today is a neutral blend of the eastern variety without its distinctive features.[49] This core is further embellished with Goalpariya and Kamrupi idioms and forms.[50]

Geographical distribution edit

Assamese is native to Assam. It is also spoken in states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Nagaland. The Assamese script can be found in of present-day Burma. The Pashupatinath Temple in Nepal also has inscriptions in Assamese showing its influence in the past.

There is a significant Assamese-speaking diaspora worldwide.[51][52][53][54]

Official status edit

Assamese is the official language of Assam, and one of the 22 official languages recognised by the Republic of India. The Assam Secretariat functions in Assamese.[55]

Phonology edit

The Assamese phonemic inventory consists of eight vowels, ten diphthongs, and twenty-three consonants (including two semivowels).[56]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i, ই/ঈ⟩ | u ⟨u, উ/ঊ⟩ | |

| Near-close | ʊ ⟨w, ও⟩ | ||

| Close-mid | e ⟨é, এʼ⟩ | o ⟨ó, অʼ⟩ | |

| Open-mid | ɛ ⟨e, এ⟩ | ɔ ⟨o, অ⟩ | |

| Open | ä ⟨a, আ⟩ |

| a | i | u | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | ai | au | |

| ɔ | ɔi | ||

| e | ei | eu | |

| o | oi | ou | |

| i | iu | ||

| u | ua | ui |

| Labial | Alveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m, ম⟩ | n ⟨n, ন/ণ⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng, ঙ/ং⟩ | ||

| Stop | voiceless | p ⟨p, প⟩ | t ⟨t, ত/ট⟩ | k ⟨k, ক⟩ | |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨ph, ফ⟩ | tʰ ⟨th, থ/ঠ⟩ | kʰ ⟨kh, খ⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b, ব⟩ | d ⟨d, দ/ড⟩ | ɡ ⟨g, গ⟩ | ||

| murmured | bʱ ⟨bh, ভ⟩ | dʱ ⟨dh, ধ/ঢ⟩ | ɡʱ ⟨gh, ঘ⟩ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | s ⟨s, চ/ছ⟩ | x ⟨x, শ/ষ/স⟩ | h ⟨h, হ⟩ | |

| voiced | z ⟨j, জ/ঝ/য⟩ | ||||

| Approximant | central | w ⟨w, ৱ⟩ | ɹ ⟨r, ৰ⟩ | j ⟨y, য়/্য (য)⟩ | |

| lateral | l ⟨l, ল⟩ | ||||

Consonant clusters edit

Alveolar stops edit

The Assamese phoneme inventory is unique in the group of Indo-Aryan languages as it lacks a dental-retroflex distinction among the coronal stops as well as the lack of postalveolar affricates and fricatives.[59] Historically, the dental and retroflex series merged into alveolar stops. This makes Assamese resemble non-Indic languages of Northeast India (such as Austroasiatic and Sino-Tibetan languages).[60] The only other language to have fronted retroflex stops into alveolars is the closely related group of eastern dialects of Bengali (although a contrast with dental stops remains in those dialects). /r/ is normally realised as [ɹ] or [ɻ].

Voiceless velar fricative edit

Assamese is unusual among Eastern Indo-Aryan languages for the presence of /x/ (realised as [x] or [χ], depending on the speaker and speech register), due historically to the MIA sibilants' lenition to /x/ (initially) and /h/ (non-initially).[61] The use of the voiceless velar fricative is heavy in the eastern Assamese dialects and decreases progressively to the west—from Kamrupi[62] to eastern Goalparia, and disappears completely in western Goalpariya.[63][64] The change of /s/ to /h/ and then to /x/ has been attributed to Tibeto-Burman influence by Suniti Kumar Chatterjee.[65]

Velar nasal edit

Assamese, Odia, and Bengali, in contrast to other Indo-Aryan languages, use the velar nasal (the English ng in sing) extensively. While in many languages, the velar nasal is commonly restricted to preceding velar sounds, in Assamese it can occur intervocalically.[56] This is another feature it shares with other languages of Northeast India, though in Assamese the velar nasal never occurs word-initially.[66]

Vowel inventory edit

Eastern Indic languages like Assamese, Bengali, Sylheti, and Odia do not have a vowel length distinction, but have a wide set of back rounded vowels. In the case of Assamese, there are four back rounded vowels that contrast phonemically, as demonstrated by the minimal set: কলা kola [kɔla] ('deaf'), ক'লা kóla [kola] ('black'), কোলা kwla [kʊla] ('lap'), and কুলা kula [kula] ('winnowing fan'). The near-close near-back rounded vowel /ʊ/ is unique in this branch of the language family. But in lower Assam, ও is pronounced the same as অ' (ó): compare কোলা kwla [kóla] and মোৰ mwr [mór].

Vowel harmony edit

Assamese has vowel harmony. The vowels [i] and [u] cause the preceding mid vowels and the high back vowels to change to [e] and [o] and [u] respectively. Assamese is one of the few languages spoken in India which exhibit a systematic process of vowel harmony.[67][68]

Schwa deletion edit

The inherent vowel in standard Assamese, /ɔ/, follows deletion rules analogous to "schwa deletion" in other Indian languages. Assamese follows a slightly different set of "schwa deletion" rules for its modern standard and early varieties. In the modern standard /ɔ/ is generally deleted in the final position unless it is (1) /w/ (ৱ); or (2) /y/ (য়) after higher vowels like /i/ (ই) or /u/ (উ);[69] though there are a few additional exceptions. The rule for deleting the final /ɔ/ was not followed in Early Assamese.

The initial /ɔ/ is never deleted.

Writing system edit

Modern Assamese uses the Assamese script. In medieval times, the script came in three varieties: Bamuniya, Garhgaya, and Kaitheli/Lakhari, which developed from the Kamarupi script. It very closely resembles the Mithilakshar script of the Maithili language, as well as the Bengali script.[70] There is a strong literary tradition from early times. Examples can be seen in edicts, land grants and copper plates of medieval kings. Assam had its own manuscript writing system on the bark of the saanchi tree in which religious texts and chronicles were written, as opposed to the pan-Indian system of Palm leaf manuscript writing. The present-day spellings in Assamese are not necessarily phonetic. Hemkosh (হেমকোষ [ɦɛmkʊx]), the second Assamese dictionary, introduced spellings based on Sanskrit, which are now the standard.

Assamese has also historically been written using the Arabic script by Assamese Muslims. One example is Tariqul Haq Fi Bayane Nurul Haq by Zulqad Ali (1796–1891) of Sivasagar, which is one of the oldest works in modern Assamese prose.[71]

In the early 1970s, it was agreed upon that the Roman script was to be the standard writing system for Nagamese Creole.[3]

Sample text edit

The following is a sample text in Assamese of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Assamese in Assamese alphabet

- ১ম অনুচ্ছেদ: জন্মগতভাৱে সকলো মানুহ মৰ্য্যদা আৰু অধিকাৰত সমান আৰু স্বতন্ত্ৰ। তেওঁলোকৰ বিবেক আছে, বুদ্ধি আছে। তেওঁলোকে প্ৰত্যেকে প্ৰত্যেকক ভ্ৰাতৃভাৱে ব্যৱহাৰ কৰা উচিত।[72]

Assamese in WRA Romanisation

- Prôthôm ônussêd: Zônmôgôtôbhawê xôkôlû manuh môrjyôda aru ôdhikarôt xôman aru sôtôntrô. Têû̃lûkôr bibêk asê, buddhi asê. Têû̃lûkê prôittêkê prôittêkôk bhratribhawê byôwôhar kôra usit.

Assamese in SRA Romanisation

- Prothom onussed: Jonmogotobhabe xokolü manuh moirjjoda aru odhikarot xoman aru sotontro. Teü̃lükor bibek ase, buddhi ase. Teü̃lüke proitteke proittekok bhratribhawe bebohar kora usit.

Assamese in SRA2 Romanisation

- Prothom onussed: Jonmogotovawe xokolu' manuh morjjoda aru odhikarot xoman aru sotontro. Teulu'kor bibek ase, buddhi ase. Teulu'ke proitteke proittekok vratrivawe bewohar kora usit.

Assamese in CCRA Romanisation

- Prothom onussed: Jonmogotobhawe xokolu manuh morjyoda aru odhikarot xoman aru sotontro. Teulukor bibek ase, buddhi ase. Teuluke proitteke proittekok bhratribhawe byowohar kora usit.

Assamese in IAST Romanisation

- Prathama anucchēda: Janmagatabhāve sakalo mānuha maryadā āru adhikārata samāna āru svatantra. Tēõlokara bibēka āchē, buddhi āchē. Tēõlokē pratyēkē pratyēkaka bhrātribhāvē byavahāra karā ucita.

Assamese in the International Phonetic Alphabet

- /pɹɔtʰɔm ɔnusːɛd | zɔnmɔɡɔtɔbʰabɛ xɔkɔlʊ manuʱ mɔɪzːɔda aɹu ɔdʰikaɹɔt xɔman aɹu sɔtɔntɹɔ || tɛʊ̃lʊkɔɹ bibɛk asɛ budːʰi asɛ || tɛʊ̃lʊkɛ pɹɔɪtːɛkɛ pɹɔɪtːɛkɔk bʰɹatɹibʰabɛ bɛbɔɦaɹ kɔɹa usit/

Gloss

- 1st Article: Congenitally all human dignity and right-in equal and free. their conscience exists, intellect exists. They everyone everyone-to brotherly behaviour to-do should.

Translation

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience. Therefore, they should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Morphology and grammar edit

The Assamese language has the following characteristic morphological features:[73]

- Gender and number are not grammatically marked.

- There is a lexical distinction of gender in the third person pronoun.

- Transitive verbs are distinguished from intransitive.

- The agentive case is overtly marked as distinct from the accusative.

- Kinship nouns are inflected for personal pronominal possession.

- Adverbs can be derived from the verb roots.

- A passive construction may be employed idiomatically.

Negation process edit

Verbs in Assamese are negated by adding /n/ before the verb, with /n/ picking up the initial vowel of the verb. For example:[74]

- /na laɡɛ/ 'do(es) not want' (1st, 2nd and 3rd persons)

- /ni likʰʊ̃/ 'will not write' (1st person)

- /nukutʊ̃/ 'will not nibble' (1st person)

- /nɛlɛkʰɛ/ 'does not count' (3rd person)

- /nɔkɔɹɔ/ 'do not do' (2nd person)

Classifiers edit

Assamese has a large collection of classifiers, which are used extensively for different kinds of objects, acquired from the Sino-Tibetan languages.[75] A few examples of the most extensive and elaborate use of classifiers are given below:

- "zɔn" is used to signify a person, male with some amount of respect

- E.g., manuh-zɔn – "the man"

- "zɔni" (female) is used after a noun or pronoun to indicate human beings

- E.g., manuh-zɔni – "the woman"

- "zɔni" is also used to express the non-human feminine

- E.g., sɔɹai zɔni – "the bird", pɔɹuwa-zɔni – "the ant"

- "zɔna" and "gɔɹaki" are used to express high respect for both man and woman

- E.g., kɔbi-zɔna – "the poet", gʊxaɪ-zɔna – "the goddess", rastrapati-gɔɹaki – "the president", tiɹʊta-gɔɹaki – "the woman"

- "tʊ" has three forms: tʊ, ta, ti

- (a) tʊ: is used to specify something, although the case of someone, e.g., loɹa-tʊ – "the particular boy", is impolite

- (b) ta: is used only after numerals, e.g., ɛta, duta, tinita – "one, two, three"

- (c) ti: is the diminutive form, e.g., kesua-ti – "the infant, besides expressing more affection or attachment to

- "kɔsa", "mɔtʰa" and "taɹ" are used for things in bunches

- E.g., sabi-kɔsa – "the bunch of key", saul-mɔtʰa – "a handful of rice", suli-taɹi or suli kɔsa – "the bunch of hair"

- dal, dali, are used after nouns to indicate something long but round and solid

- E.g., bãʱ-dal – "the bamboo", katʰ-dal – "the piece of wood", bãʱ-dali – "the piece of bamboo"

| Classifier | Referent | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| /zɔn/ | males (adult) | manuh-zɔn (the man – honorific) |

| /zɔni/ | females (women as well as animals) | manuh-zɔni (the woman), sɔrai-zɔni (the bird) |

| /zɔna/ | honorific | kobi-zɔna (the poet), gʊxai-zɔna (the god/goddess) |

| /ɡɔɹaki/ | males and females (honorific) | manuh-ɡɔɹaki (the woman), rastrɔpɔti-gɔɹaki (the president) |

| /tʊ/ | inanimate objects or males of animals and men (impolite) | manuh-tʊ (the man – diminutive), gɔɹu-tʊ (the cow) |

| /ti/ | inanimate objects or infants | kesua-ti (the baby) |

| /ta/ | for counting numerals | e-ta (count one), du-ta (count two) |

| /kʰɔn/ | flat square or rectangular objects, big or small, long or short | |

| /kʰɔni/ | terrain like rivers and mountains | |

| /tʰupi/ | small objects | |

| /zak/ | group of people, cattle; also for rain; cyclone | |

| /sati/ | breeze | |

| /pat/ | objects that are thin, flat, wide or narrow. | |

| /paɦi/ | flowers | |

| /sɔta/ | objects that are solid | |

| /kɔsa/ | mass nouns | |

| /mɔtʰa/ | bundles of objects | |

| /mutʰi/ | smaller bundles of objects | |

| /taɹ/ | broomlike objects | |

| /ɡɔs/ | wick-like objects | |

| /ɡɔsi/ | with earthen lamp or old style kerosene lamp used in Assam | |

| /zʊpa/ | objects like trees and shrubs | |

| /kʰila/ | paper and leaf-like objects | |

| /kʰini/ | uncountable mass nouns and pronouns | |

| /dal/ | inanimate flexible/stiff or oblong objects; humans (pejorative) |

In Assamese, classifiers are generally used in the numeral + classifier + noun (e.g. /ezɔn manuh/ ejon manuh 'one man') or the noun + numeral + classifier (e.g. /manuh ezɔn/ manuh ejon 'one man') forms.

Nominalization edit

Most verbs can be converted into nouns by the addition of the suffix /ɔn/. For example, /kʰa/ ('to eat') can be converted to /kʰaɔn/ khaon ('good eating').[76]

Grammatical cases edit

Assamese has 8 grammatical cases:

| Cases | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Absolutive | none | বাৰীত barit garden-LOC গৰু góru- cattle-ABS সোমাল। xwmal. entered Cattles entered into the garden. |

| Ergative | -এ, -e, -ই -i |

গৰুৱে góru-e cattle-ERG ঘাঁহ ghãh grass-ACC খায়। kha-e. eat-3.HAB.PRES Cattles eat grass. Note: The personal pronouns without a plural or other suffix are not marked. |

| Accusative | -(অ)ক, -(o)k, − − |

শিয়ালটোৱে xial-tw-e jackal-the-ERG শহাটোক xoha-tw-k hare-the-ACC খেদি khedi chasing আছে। ase. exist-3.PRES.CONT The jackal is chasing the hare. তেওঁলোকে tewlwk-e they চোৰটো sür-tw- thief-the-ACC পুলিচক pulis-ok police-ACC গতালে। gotale. handover-REC-3 They handed over the thief to the police. |

| Genitive | -(অ)ৰ -(o)r |

তাইৰ tai-r she-GEN ঘৰ ghor house Her house |

| Dative | -(অ)লৈ -(o)lói [dialectal: [dialectal: -(অ)লে]; -(o)le]; -(অ)ক -(o)k |

সি xi he পঢ়াশালিলৈ porhaxali-lói school-DAT গৈ gói going আছে। ase. exist-3.PRES.CONT He is going to (the) school. বাক ba-k elder sister-DAT চাবিটো sabi-tw- key-the-ACC দিয়া। dia. give-FAM.IMP Give elder sister the key. |

| Terminative | -(অ)লৈকে -(o)lóike [dialectal: [dialectal: -(অ)লেকে] -(o)leke] |

মই moi I নহালৈকে n-oha-lóike not-coming-TERM কʼতো kót-w where-even নেযাবা। ne-ja-b-a. not-go-future-3 Don't go anywhere until I don't come. ১ৰ 1-or one-GEN পৰা pora from ৭লৈকে 7-olóike seven-TERM From 1 up to 7 |

| Instrumental | -(এ)ৰে -(e)re [dialectal: [dialectical: -(এ)দি] -(e)di] |

কলমেৰে kolom-ere pen-INS লিখিছিলা। likhisila. write-2.DP You wrote with (a) pen. |

| Locative | -(অ)ত -(o)t [sometimes: [sometimes: -এ] -e] |

সি xi he বহীখনত bóhi-khon-ot notebook-the-LOC লিখিছে। likhise. write-PRES.PERF.3 He has written on the notebook. আইতা aita grandmother মঙলবাৰে moŋolbar-e Tuesday-LOC আহিছিল। ahisil. come-DP-3 Grandmother came on Tuesday. |

Pronouns edit

| Number | Person | Gender | Pronouns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutive Ergative |

Accusative Dative |

Genitive | Locative | Dative | |||

| Singular | 1st | m/f (I) | moi | mwk | mwr | mwt | mwlói |

| 2nd | m/f (you) | toi ᵛ tumi ᶠ apuni ᵖ |

twk twmak apwnak |

twr twmar apwnar |

twt twmat apwnat |

twloi twmalói apwnaloi | |

| 3rd | m (he) n (it, that) |

i * xi ** |

iak tak |

iar tar |

iat tat |

ialoi taloi | |

| f (she) | ei * tai ** |

eik taik |

eir tair |

eit tait |

eilói tailói | ||

| n & p (he/she) | ew/ekhet(-e ᵉ) * teü/tekhet(-e ᵉ) ** |

ewk/ekhetok tewk/tekhetok |

ewr/ekhetor tewr/tekhetor |

ewt/ekhetot tewt/tekhetot |

ewloi/ekhetólói tewlói/tekhetólói | ||

| Plural | 1st | m/f (we) | ami | amak | amar | amat | amalói |

| 2nd | m/f (you) | tohot(-e ᵉ) ᵛ twmalwk(-e ᵉ) ᶠ apwnalwk(-e ᵉ) ᵖ |

tohõtok twmalwkok apwnalwkok |

tohõtor twmalwkor apwnalwkor |

tohõtot twmalwkot apwnalwkot |

tohõtolói twmalwkolói apwnalwkolói | |

| 3rd | m/f (they) | ihõt * ewlwk/ekhetxokol(-e ᵉ) ᵖ * xihõt ** tewlwk/tekhetxokol(-e ᵉ) ᵖ ** |

ihõtok xihotõk ewlwkok/ekhetxokolok tewlwkok/tekhetxokolok |

ihõtor xihotõr eülwkor/ekhetxokolor tewlwkor/tekhetxokolor |

ihõtot xihotõt ewlwkot/ekhetxokolot tewlwkot/tekhetxokolot |

ihõtoloi xihotõloi ewlwkok/ekhetxokololoi tewlwkoloi/tekhetxokololoi | |

| n (these, those) | eibwr(-e ᵉ) ᵛ * eibilak(-e ᵉ) ᶠ * eixómuh(-e ᵉ) ᵖ * xeibwr(-e ᵉ) ᵛ ** xeibilak(-e ᵉ) ᶠ ** xeixómuh(-e) ᵖ ** |

eibwrok eibilakok eixómuhok xeibwrok xeibilakok xeixómuhok |

eibwror eibilakor eixómuhor xeibwror xeibilakor xeixómuhor |

eibwrot eibilakot eixómuhot xeibwrot xeibilakot xeixómuhot |

eibwrolói eibilakolói eixómuholói xeibwroloi xeibilakoleó xeixómuhólói | ||

m=male, f=female, n=neuter., *=the person or object is near., **=the person or object is far., v =very familiar, inferior, f=familiar, p=polite, e=ergative form.

Tense edit

With consonant ending verb likh (write) and vowel ending verb kha (eat, drink, consume).

| Stem | Likh, Kha |

|---|---|

| Gerund | Likha, khwa |

| Causative | Likha, khua |

| Conjugative | Likhi, Khai & Kha |

| Infinitive | Likhibó, Khabo |

| Goal | Likhibólói, Khabólói |

| Terminative | Likhibólóike, Khabólóike |

| Agentive | Likhüta np/Likhwra mi/Likhwri fi, Khawta np/Khawra mi/Khawri fi |

| Converb | Likhwte, Khawte |

| Progressive | Likhwte likhwte, Khawte khawte |

| Reason | Likhat, Khwat |

| Likhilot, Khalot | |

| Conditional | Likhile, Khale |

| Perfective | Likhi, Khai |

| Habitual | Likhi likhi, Khai khai |

For different types of verbs.

| Tense | Person | tho "put" | kha "consume" | pi "drink" | de "give" | dhu "wash" | kor "do" | randh "cook" | ah "come" | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - | ||

| Simple Present | 1st per. | thow | nothow | khaw | nakhaw ~ nekhaw | piw | nipiw | diw | nidiw | dhw | nudhw | korw | nokorw | randhw | narandhw ~ nerandhw | ahw | nahw |

| 2nd per. inf. | thwa | nothwa | khwa | nakhwa ~ nekhwa | piua | nipiua | dia | nidia | dhua | nudhua | kora | nokora | randha | narandha ~ nerandha | aha | naha | |

| 2nd per. pol. | thwa | nwthwa | khwa | nwkhwa | piua | nipiua | dia | nidia | dhwa | nwdhwa | kora | nokora | randha | narandha ~ nerandha | aha | naha | |

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thoe | nothoe | khae | nakhae ~ nekhae | pie | nipie | die | nidie | dhwe | nudhwe | kore | nokore | randhe | narandhe ~ nerandhe | ahe | nahe | |

| Present continuous | 1st per. | thói asw | thoi thoka nai | khai asw | khai thoka nai | pi asu | pi thoka nai | di asw | di thoka nai | dhui asw | dhui thoka nai | kori asw | kóri thoka nai | randhi asw | randhi thoka nai | ahi asw | ahi thoka nai |

| 2nd per. inf. | thoi aso | khai aso | pi aso | di aso | dhui aso | kori aso | randhi aso | ahi aso | |||||||||

| 2nd per. pol. | thoi asa | khai asa | pi asa | di asa | dhui asa | kori asa | randhi asa | ahi asa | |||||||||

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thoi ase | khai ase | pi ase | di ase | dhui ase | kori ase | randhi ase | ahi ase | |||||||||

| Present Perfect | 1st per. | thoisw | thwa nai | khaisw | khwa nai | pisw | pia nai | disw | dia nai | dhui asw | dhwa nai | korisw | kora nai | randhisw | rondha nai | ahi asw | oha nai |

| 2nd per. inf. | thóisó | khaisó | pisó | disó | dhuisó | kórisó | randhisó | ahisó | |||||||||

| 2nd per. pol. | thoisa | khaisa | pisa | disa | dhuisa | korisa | randhisa | ahisa | |||||||||

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thoise | khaise | pise | dise | dhuise | korise | randhise | ahise | |||||||||

| Recent Past | 1st per. | thölw | nothölw | khalw | nakhalw ~ nekhalw | pilw | nipilw | dilw | nidilw | dhulw | nudhulw | korilw | nokórilw | randhilw | narandhilw ~ nerandhilw | ahilw | nahilw |

| 2nd per. inf. | thöli | nothöli | khali | nakhali ~ nekhali | pili | nipili | dili | nidili | dhuli | nudhuli | kórili | nókórili | randhili | narandhili ~ nerandhili | ahilw | nahilw | |

| 2nd per. pol. | thöla | nothöla | khala | nakhala ~ nekhala | pila | nipila | dila | nidila | dhula | nudhula | kórila | nókórila | randhila | narandhila ~ nerandhila | ahila | nahila | |

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thöle | nothöle | khale | nakhale ~ nekhale | pile | nipile | dile | nidile | dhule | nudhule | kórile | nókórile | randhile | narandhile ~ nerandhile | ahile / ahiltr | nahile / nahiltr | |

| Distant Past | 1st per. | thoisilw | nothoisilw ~ thwa nasilw | khaisilw | nakhaisilw ~ nekhaisilw ~ khwa nasilw | pisilw | nipisilw ~ pia nasilw | disilw | nidisilw ~ dia nasilw | dhuisilw | nudhuisilw ~ dhüa nasilw | kórisilw | nókórisilw ~ kora nasilw | randhisilw | narandhisilw ~ nerandhisilw ~ rondha nasilw | ahisilw | nahisilw ~ oha nasilw |

| 2nd per. inf. | thoisili | nothóisili ~ thwa nasili | khaisili | nakhaisili ~ nekhaisili ~ khwa nasili | pisili | nipisili ~ pia nasili | disili | nidisili ~ dia nasili | dhuisili | nudhuisili ~ dhwa nasili | korisili | nokorisili ~ kora nasili | randhisili | narandhisili ~ nerandhisili ~ rondha nasili | ahisili | nahisili ~ oha nasili | |

| 2nd per. pol. | thoisila | nothóisila ~ thwa nasila | khaisila | nakhaisila ~ nekhaisila ~ khüa nasila | pisila | nipisila ~ pia nasila | disila | nidisila ~ dia nasila | dhuisila | nudhuisila ~ dhwa nasila | korisila | nokorisila ~ kora nasila | randhisila | narandhisila ~ nerandhisila ~ rondha nasila | ahisila | nahisila ~ oha nasila | |

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thoisile | nothoisile ~ thwa nasile | khaisile | nakhaisile ~ nekhaisile ~ khwa nasile | pisile | nipisile ~ pia nasile | disile | nidisile ~ dia nasile | dhuisile | nudhuisile ~ dhüa nasile | korisile | nokorisile ~ kora nasile | randhisile | narandhisile ~ nerandhisile ~ rondha nasile | ahisile | nahisile ~ oha nasile | |

| Past continuous | 1st per. | thoi asilw | thoi thoka nasilw | khai asilw | khai thoka nasilw | pi asilw | pi thoka nasilw | di asilw | di thoka nasilw | dhui asils | dhui thoka nasils | kori asils | kori thoka nasils | randhi asils | randhi thoka nasils | ahi asils | ahi thoka nasils |

| 2nd per. inf. | thoi asili | thoi thoka nasili | khai asili | khai thoka nasili | pi asili | pi thoka nasili | di asili | di thoka nasili | dhui asili | dhui thoka nasili | kori asili | kori thoka nasili | randhi asili | randhi thoka nasili | ahi asili | ahi thoka nasili | |

| 2nd per. pol. | thoi asila | thoi thoka nasila | khai asila | khai thoka nasila | pi asila | pi thoka nasila | di asila | di thoka nasila | dhui asila | dhui thoka nasila | kori asila | kori thoka nasila | randhi asila | randhi thoka nasila | ahi asila | ahi thoka nasila | |

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thoi asil(e) | thoi thoka nasil(e) | khai asil(e) | khai thoka nasil(e) | pi asil(e) | pi thoka nasil(e) | di asil(e) | di thoka nasil(e) | dhui asil(e) | dhui thoka nasil(e) | kori asil(e) | kori thoka nasil(e) | randhi asil(e) | randhi thoka nasil(e) | ahi asil{e) | ahi thoka nasil(e) | |

| Simple Future | 1st per. | thöm | nothöm | kham | nakham ~ nekham | pim | nipim | dim | nidim | dhum | nudhum | korim | nokorim | randhim | narandhim ~ nerandhim | ahim | nahim |

| 2nd per. inf. | thöbi | nothöbi | khabi | nakhabi ~ nekhabi | pibi | nipibi | dibi | nidibi | dhubi | nudhubi | koribi | nokoribi | randhibi | narandhibi ~ nerandhibi | ahibi | nahibi | |

| 2nd per. pol. | thöba | nothöba | khaba | nakhaba ~ nekhaba | piba | nipiba | diba | nidiba | dhuba | nudhuba | koriba | nókóriba | randhiba | narandhiba ~ nerandhiba | ahiba | nahiba | |

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thöbo | nothöbo | khabo | nakhabo ~ nekhabo | pibo | nipibo | dibo | nidibo | dhubo | nudhubo | koribo | nokoribo | randhibo | narandhibo ~ nerandhibo | ahibo | nahibo | |

| Future continuous | 1st per. | thoi thakim | thoi nathakim/nethakim | khai thakim | khai nathakim/nethakim | pi thakim | pi nathakim/nethakim | di thakim | di nathakim/nethakim | dhui thakim | dhui nathakim/nethakim | kori thakim | kori nathakim/nethakim | randhi thakim | randhi nathakim/nethakim | ahi thakim | ahi nathakim/nethakim |

| 2nd per. inf. | thoi thakibi | thoi nathakibi/nethakibi | khai thakibi | khai nathakibi/nethakibi | pi thakibi | pi nathakibi/nethakibi | di thakibi | di nathakibi/nethakibi | dhui thakibi | dhui nathakibi/nethakibi | kori thakibi | kori nathakibi/nethakibi | randhi thakibi | randhi nathakibi/nethakibi | ahi thakibi | ahi nathakibi/nethakibi | |

| 2nd per. pol. | thoi thakiba | thoi nathakiba/nethakiba | khai thakiba | khai nathakiba/nethakiba | pi thakiba | pi nathakiba/nethakiba | di thakiba | di nathakiba/nethakiba | dhui thakiba | dhui nathakiba/nethakiba | kori thakiba | kori nathakiba/nethakiba | randhi thakiba | randhi nathakiba/nethakiba | ahi thakiba | ahi nathakiba/nethakiba | |

| 2nd per. hon. & 3rd per. | thoi thakibo | thoi nathakibo/nethakibo | khai thakibo | khai nathakibo/nethakibo | pi thakibo | pi nathakibo/nethakibo | di thakibo | di nathakibo/nethakibo | dhui thakibo | dhui nathakibo/nethakibo | kori thakibo | kori nathakibo/nethakibo | randhi thakibo | randhi nathakibo/nethakibo | ahi thakibo | ahi nathakibo/nethakibo | |

The negative forms are n + 1st vowel of the verb + the verb. Example: Moi porhw, Moi noporhw (I read, I do not read); Tumi khelila, Tumi nekhelila (You played, You didn't play). For verbs that start with a vowel, just the n- is added, without vowel lengthening. In some dialects if the 1st vowel is a in a verb that starts with consonant, ne is used, like, Moi nakhaw (I don't eat) is Moi nekhaü. In past continuous the negative form is -i thoka nasil-. In future continuous it's -i na(/e)thaki-. In present continuous and present perfect, just -i thoka nai and -a nai' respectively are used for all personal pronouns. Sometimes for plural pronouns, the -hok suffix is used, like korwhok (we do), ahilahok (you guys came).Content

Relationship suffixes edit

| Persons | Suffix | Example | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | none | Mwr/Amar ma, bap, kokai, vai, ba, voni | My/Our mother, father, elder-brother, younger-brother, elder-sister, younger-sister |

| 2nd person (very familiar; inferior) |

-(e)r | Twr/Tohõtor mar, baper, kokaier, vaier, bar, vonier | Your/Your(pl) mother, father, elder-brother, younger-brother, elder-sister, younger-sister |

| 2nd person familiar |

-(e)ra | Twmar/Twmalwkor mara, bapera, kokaiera, vaiera, bara, voniera | Your/Your(pl) mother, father, elder-brother, younger-brother, elder-sister, younger-sister |

| 2nd person formal; 3rd person |

-(e)k | Apwnar/Apwnalwkor/Tar/Tair/Xihotõr/Tewr mak, bapek, kokaiek, bhaiek, bak, voniek | Your/Your(pl)/His/Her/Their/His~Her(formal) mother, father, elder-brother, younger-brother, elder-sister, younger-sister |

Dialects edit

Regional dialects edit

The language has quite a few regional variations. Banikanta Kakati identified two broad dialects which he named (1) Eastern and (2) Western dialects,[77] of which the eastern dialect is homogeneous, and prevalent to the east of Guwahati, and the western dialect is heterogeneous. However, recent linguistic studies have identified four dialect groups listed below from east to west:[56]

- Eastern group in and around the undivided Sivasagar district (Golaghat, Jorhat, Majuli, Charaideo and Sivasagar) and the former undivided Lakhimpur district (Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Lakhimpur and Dhemaji. Standard Assamese is based on the Eastern group.

- Central group spoken in Nagaon, Sonitpur, Morigaon districts and adjoining areas

- Kamrupi group in the Kamrup region: (Barpetia, Nalbariya, Palasbaria)

- Goalpariya group in the Goalpara region: (Ghulliya, Jharuwa, Caruwa)

Samples edit

Collected from the book, Assamese – Its formation and development.[78] The text bellow is from the Parable of the Prodigal Son. The translations are of different versions of the English translations:

English: A man had two sons. The younger son told his father, 'I want my share of your estate now before you die.' So his father agreed to divide his wealth between his sons. A few days later this younger son packed all his belongings and moved to a distant land, and there he wasted all his money in wild living. About the time his money ran out, a great famine swept over the land, and he began to starve. He persuaded a local farmer to hire him, and the man sent him into his fields to feed the pigs. The young man became so hungry that even the pods he was feeding the pigs looked good to him. But no one gave him anything.

Eastern Assamese (Sibsagar): Künü ejon manuhor duta putek asil, tare xorutüe bapekok kole, "Oi büpai! xompottir ji bhag moi paü tak mük diok!" Tate teü teür xompotti duiü putekor bhitorot bati dile. Olop dinor pasot xorutw puteke tar bhagot ji pale take loi dur dexoloi goi beisali kori gutei xompotti nax korile. Tar pasot xei dexot bor akal hól. Tate xi dux paboloi dhorile. Tetia xi goi xei dexor ejon manuhor asroy lole, aru xei manuhe tak gahori soraboloi potharoloi pothai dile. Tate xi gahorir khüa ebidh gosor seire pet bhoraboloi bor hepah korileü tak küneü ekü nidile.

Central Assamese: Manuh ejonor duta putak asil. Tahãtor vitorot xoutw putake bapekok kóle,

Central/Kamrupi (Pati Darrang): Eta manhur duta putak asil, xehatör xorutui bapakök kolak, "He pite, xompöttir mör bhagöt zikhini porei, take mök di." Tate teö nizör xompötti xehatök bhagei dilak. Tar olop dinör pasötei xeñ xoru putektüi xokolöke götei loi kömba dexok legi polei gel aru tate lompot kamöt götei urei dilak. Xi xokolö bioe koraõte xeñ dexöt bor akal hol. Xi tate bor kosto paba dhollak. Teten xi aru xeñ dexor eta manhur asroe lolak. Xeñ mantui nizör potharök legi tak bora saribak legi pothei dilak. Tate xi aru borai khawa ekbidh gasör sei di pet bhorabak legi bor hepah kollak. Kintu kawei ekö tak nedlak.

Kamrupi (Palasbari): Kunba eta manhur duta putak asil. Ekdin xortö putake bapiakok kola, "Bapa wa, apunar xompöttir moi bhagöt zeman kheni pam teman khini mök dia." Tethane bapiake nizör xompötti duö putakok bhage dila. Keidinman pasöt xörtö putake tar bhagtö loi kunba akhan durher dekhok gel, aru tate gundami köri tar götei makha xompötti nohoa koilla. Tar pasöt xiai dekhot mosto akal hol. Tethian xi bor dukh paba dhoilla. Tar xi tarei eta manhur osarök zai asroe asroe lola. Manhtöi tak bara sarba potharöl khedala. Tate xi barai khawa ekbidh gasör seṅ khaba dhoilla. Teö tak kayö akö khaba neidla.

Kamrupi (Barpeta): Kunba eta manhör duta putek asil. Ekdin xorutu puteke bapekök kolak, "Pita, amar xompöttir moi zikhini mör bhagöt paü xikhini mök dia." Tethen bapeke nizör xompötti tahak bhage dilak. Tare keidinmen pisöte xei xoru putektui tar gotexopake loi ekhen duhrer dekhök gusi gel, arö tate xi lompot hoi tar gotexopa xompöttike ure phellak. Tar pasöt xei dekhkhenöt mosto akal hol. Tethen xi xei dekhör eta manhör osröt zai asroe lolak. Manuhtui tak bara sarbak login patharök khedolak. Tate xi ekbidh barai khawa gasör sẽi khaba dhollak. Take dekhiö kayö tak ekö khaba nedlak.

Western Goalpariya (Salkocha): Kunö ekzon mansir duizon saöa asil. Tar sötotae bapok koil, "Baba sompöttir ze bhag mör, tak mök de." Tat oë nizer sompötti umak batia dil. Tar olpo din pasöte öi söta saöata sök götea dur desot gel. Ore lompot beboharot or sompötti uzar koril. Oë götay khoros korar pasöt oi desot boro akal hoil. Ote oya kosto paba dhoril. Sela oë zaya öi deser ekzon mansir asroe löat öi manusi ok suar soraba patharot pothea dil. Ote suare khaöa ek rokom gaser sal dia pet bhoroba saileö ok kaho kisu nadil.

Non-regional dialects edit

Assamese does not have many caste- or occupation-based dialects.[79] In the nineteenth century, the Eastern dialect became the standard dialect because it witnessed more literary activity and it was more uniform from east of Guwahati to Sadiya,[80] whereas the western dialects were more heterogeneous.[81] Since the nineteenth century, the center of literary activity (as well as of politics and commerce) has shifted to Guwahati; as a result, the standard dialect has evolved considerably away from the largely rural Eastern dialects and has become more urban and acquired western dialectal elements.[82] Most literary activity takes place in this dialect, and is often called the likhito-bhaxa, though regional dialects are often used in novels and other creative works.

In addition to the regional variants, sub-regional, community-based dialects are also prevalent, namely:

- Standard dialect influenced by surrounding centers.

- Bhakatiya dialect highly polite, a sattra-based dialect with a different set of nominals, pronominals, and verbal forms, as well as a preference for euphemism; indirect and passive expressions.[83] Some of these features are used in the standard dialect on very formal occasions.

- The fisherman community has a dialect that is used in the central and eastern region.

- The astrologer community of Darrang district has a dialect called thar that is coded and secretive. The ratikhowa and bhitarpanthiya secretive cult-based Vaisnava groups too have their own dialects.[84]

- The Muslim community have their own dialectal preference, with their own kinship, custom, and religious terms, with those in east Assam having distinct phonetic features.[82]

- The urban adolescent and youth communities (for example, Guwahati) have exotic, hybrid and local slangs.[82]

- Ethnic speech communities that use Assamese as a second language, often use dialects that are influenced heavily by the pronunciation, intonation, stress, vocabulary and syntax of their respective first languages (Mising Eastern Assamese, Bodo Central Kamrupi, Rabha Eastern Goalpariya etc.).[84] Two independent pidgins/creoles, associated with the Assamese language, are Nagamese (used by Naga groups) and Nefamese (used in Arunachal Pradesh).[85]

Literature edit

There is a growing and strong body of literature in this language. The first characteristics of this language are seen in the Charyapadas composed in between the eighth and twelfth centuries. The first examples emerged in writings of court poets in the fourteenth century, the finest example of which is Madhav Kandali's Saptakanda Ramayana. The popular ballad in the form of Ojapali is also regarded as well-crafted. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a flourishing of Vaishnavite literature, leading up to the emergence of modern forms of literature in the late nineteenth century.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ a b Assamese at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "SEAlang Library Ahom Lexicography". sealang.net.

- ^ a b Bhattacharjya, Dwijen (2001). The genesis and development of Nagamese: Its social history and linguistic structure (PhD). City University of New York. ProQuest 304688285.

- ^ "Assamese". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ Assamese is an anglicized term used for the language, but scholars have also used Asamiya (Moral 1992, Goswami & Tamuli 2003) or Asomiya as a close approximation of /ɔxɔmijɑ/, the word used by the speakers for their language. (Mahanta 2012:217)

- ^ "Axomiya is the major language spoken in Assam, and serves almost as a lingua franca among the different speech communities in the whole area." (Goswami 2003:394)

- ^ Masica (1993, p. 5)

- ^ "...Rajbangshi dialect of the Rangpur Division (Bangladesh), and the adjacent Indian Districts of Jalpaiguri and Cooch Behar, has been classed with Bengali because its speakers identify with the Bengali culture and literary language, although it is linguistically closer to Assamese." (Masica 1993, p. 25)

- ^ a b "Incidentally, literate Ahoms retained the Tai language and script well until the end of the 17th century. In that century of Ahom-Mughal conflicts, this language first coexisted with and then was progressively replaced by Assamese (Asamiya) at and outside the Court." Guha (1983, p. 9)

- ^ Sen, Sukumar (1975), Grammatical sketches of Indian languages with comparative vocabulary and texts, Volume 1, P 31

- ^ a b "Dr. S. K. Chatterji basing his conclusions on the materials accumulated in LSI, Part I, and other monographs on the Bengali dialects, divides Eastern Mag. Pkt. and Ap. into four dialect groups. (1) Raddha dialects which comprehend Western Bengali which gives standard Bengali colloquial and Oriya in the South West. (2) Varendra dialects of North Central Bengal. (3) Kumarupa dialects which comprehend Assamese and the dialects of North Bengal. (4) Vanga dialects which comprehend the dialects of East Bengal (ODBL VolI p140)." (Kakati 1941, p. 6)

- ^ Proto-Kamta took its inheritance from ?proto-Kamarupa (and before that from ?proto-Gauda-Kamarupa), innovated the unique features ... in 1250-1550 AD" (Toulmin 2006:306)

- ^ "Asamiya has historically originated in Old Indo-Aryan dialects, but the exact nature of its origin and growth is not very clear as yet." (Goswami 2003:394)

- ^ There is evidence that the Prakrit of the Kamarupa kingdom differed enough from the Magadhi Prakrit to be identified as either a parallel Kamrupi Prakrit or at least an eastern variety of the Magadha Prakrit (Sharma 1990:0.24–0.28)

- ^ 'One of the interesting theories propounded by Sri Medhi is the classification of Assamese "as a mixture of Eastern and Western groups" or a "mixture of Sauraseni and Magadhi". But whether it is word resemblance or grammatical resemblance, the author admits that in some cases they may be accidental. But he says, "In any case, they may be of some help to scholars for more searching enquiry in future".' (Pattanayak 2016:43–44)

- ^ a b "While Kakati's assertion of an Austroasiatic substrate needs to be re-established on the basis of more systematic evidence, it is consistent with the general assumption that the lower Brahmaputra drainage was originally Austroasiatic speaking. It also implies the existence of a substantial Austroasiatic speaking population till the time of spread of Aryan culture into Assam, i.e. it implies that up until the 4th-5th centuries CE and probably much later Tibeto-Burman languages had not completely supplanted Austroasiatic languages." (DeLancey 2012:13)

- ^ "(W)e should imagine a linguistic patchwork with an eastern Indo-Aryan vernacular (not yet really "Assamese") in the urban centers and along the river and Tibeto-Burman and Austroasiatic communities everywhere." (DeLancey 2012:15–16)

- ^ "It is curious to find that according to (Hiuen Tsang) the language of Kamarupa 'differed a little' from that of mid-India. Hiuen Tsang is silent about the language of Pundra-vardhana or Karna-Suvarna; it can be presumed that the language of these tracts was identical with that of Magadha." (Chatterji 1926, p. 78)

- ^ "Perhaps this 'differing a little' of the Kamarupa speech refers to those modifications of Aryan sounds which now characterise Assamese as well as North- and East-Bengali dialects." (Chatterji 1926, pp. 78–89)

- ^ "When [the Tibeto-Burman speakers] adopted that language they also enriched it with their vocabularies, expressions, affixes etc." (Saikia 1997)

- ^ Moral 1997, pp. 43–53.

- ^ "... (it shows) that in Ancient Assam there were three languages viz. (1) Sanskrit as the official language and the language of the learned few, (2) Non-Aryan tribal languages of the Austric and Tibeto-Burman families, and (3) a local variety of Prakrit (ie a MIA) wherefrom, in course of time, the modern Assamese language as a MIL, emerged." Sharma, Mukunda Madhava (1978). Inscriptions of Ancient Assam. Guwahati, Assam: Gauhati University. pp. xxiv–xxviii. OCLC 559914946.

- ^ Medhi 1988, pp. 67–63.

- ^ "The earliest specimen of Assamese language and literature is available in the dohās, known also as Caryās, written by the Buddhist Siddhacharyas hailing from different parts of eastern India. Some of them are identified as belonging to ancient Kāmarūpa by the Sino-Tibetologists." (Goswami 2003:433)

- ^ "The language of [charyapadas] was also claimed to be early Assamese and early Bihari (Eastern Hindi) by various scholars. Although no systematic scientific study has been undertaken on the basis of comparative reconstruction, a cursory look is enough to suggest that the language of these texts represents a stage when the North-Eastern Prakrit was either not differentiated or at an early stage of differentiation into the regional languages of North-Eastern India." (Pattanayak 2016:127)

- ^ "The folk-song like Deh Bicarar Git and some aphorisms are found to contain sometimes the spirit and way of expression of the charyapadas." (Saikia 1997:5)

- ^ ""There are some works of the period between 12th and 14th centuries, which kept the literary tradition flowing after the period of the charyapadas. They are Sunya Puran of Ramai Pandit, Krishna Kirtan of Boru Chandi Das, Gopichandrar Gan of Sukur Mamud. Along with these three works Gobindachandrar Git of Durllava Mullik and Mainamatirgan of Bhavani Das also deserve mention here." (Saikia 1997:5)

- ^ "No doubt some expression close to the Bengali language can be found in these works. But grammatical peculiarities prove these works to be in the Assamese language of the western part of Assam." (Saikia 1997:5)

- ^ "In Krishna Kirtana for instance, the first personal affixes of the present indicative are -i and -o; the former is found in Bengali at present and the later in Assamese. Similarly the negative particle na- assimilated to the initial vowel of the conjugated root which is characteristic of Assamese is also found in Krishna Kirtana. Modern Bengali places the negative particle after the conjugated root." (Kakati 1953:5)

- ^ "In summary, none of Pattanayak's changes are diagnostic of a unique proto Bangla-Asamiya subgroup that also includes proto Kamta.... Grierson's contention may well be true that 'Gauḍa Apabhraṁśa' was the parent speech both of Kamrupa and today's Bengal (see quote under §7.3.2), but it has not yet been proven as such by careful historical linguistic reconstruction." and "Though it has not been the purpose of this study to reconstruct higher level proto-languages beyond proto-Kamta, the reconstruction here has turned up three morphological innovations—[MI 73.] (diagnostic), [MI 2] (supportive), [MI 70] (supportive)—which provide some evidence for a proto-language which may be termed proto Gauḍa-Kamrupa." (Toulmin 2009:213)

- ^ "However, the earliest literary work available which may be claimed as distinctly Asamiya is the Prahrāda Carita written by a court poet named Hema Sarasvatī in the latter half of the thirteenth century AD.(Goswami 2003:433)

- ^ a b c d e (Goswami 2003:434)

- ^ (Kakati 1953:5)

- ^ "The phonological and morphological reconstruction of the present study has found three morphological innovations that give some answers to these questions: [MI 67.] (diagnostic), [MI 22.] (supportive), and [MI 23.] (supportive). These changes provide evidence for a proto Kamrupa stage of linguistic history—ancestral to proto-Kamta and proto eastern-Kamrupa (Asamiya). However, a thorough KRDS-andAsamiya-wide reconstruction of linguistic history is required before this protostage can be robustly established." (Toulmin 2009:214)

- ^ "Sankaradeva (1449–1567) brought about a Vaishnavite revival accompanied by a revival of the language and literature." (Goswami 2003:434)

- ^ "[Bhattadev's] prose was an artificial one and yet it preserves certain grammatical peculiarities. The first personal ending -m in the future tense appears for the first time in writing side by side with the conventional -bo." (Kakati 1953:6)

- ^ a b (Kakati 1953:6)

- ^ (Kakati 1953:7)

- ^ "The British administration introduced Bangla in all offices, in the courts and schools of Assam." (Goswami 2003:435)

- ^ "By 1772, the Company had skillfully employed the sword, diplomacy, and intrigue to take over the rule of Bengal from her people, factious nobles, and weak Nawab. Subsequently, to consolidate its hold on the province, the Company promoted the Bengali language. This did not represent an intrinsic love for Bengali speech and literature. Instead it was aimed at destroying traditional patterns of authority through supplanting the Persian language which had been the official tongue since the days of the great Moguls." (Khan 1962:53)

- ^ "[W]e should not assent to uphold a corrupt dialect, but endeavour to introduce pure Bengallee, and to render this Province as far as possible an integral part of the great country to which that language belongs, and to render available to Assam the literature of Bengal. - This brief aside of Francis Jenkins in a Revenue Consultation remains one of the clearest policy statements of the early British Indian administration regarding the vernacular question in Assam." (Kar 2008:28)

- ^ (Kar 2008:40–45)

- ^ "He wrote under a pen name, A Native, a book in English, A Few Remarks on the Assamese Language and on Vernacular Education in Assam, 1855, and had 100 copies of it printed by A H Danforth at the Sibsagar Baptist Mission Press. One copy of the publication was sent to the Government of Bengal and other copies were distributed free among leading men of Assam. An abstract of this was published later in The Indian Antiquary (1897, p57)". (Neog 1980:15)

- ^ "In less than twenty years' time, the government actually revised its classification and declared Assamese as the official vernacular of the Assam Division (19 April 1873), as a prelude to the constitution of a separate Chief Commissionership of Assam (6 February 1874)." (Kar 2008:45)

- ^ (Kar 2008:38)

- ^ (Kar 2008:46–47)

- ^ (Kar 2008:51–55)

- ^ "They looked back to the fully mature prose of the historical writings of earlier periods, which possessed all the strength and vitality to stand the new challenge. Hemchandra Barua and his followers immediately reverted to the syntax and style of that prose, and Sanskritized the orthography and spelling system entirely. He was followed by one and all including the missionaries themselves, in their later writings. And thus, the solid plinth of the modern standard language was founded and accepted as the norm all over the state." (Goswami 2003:435)

- ^ "In contemporary Assam, for the purposes of mass media and communication, a certain neutral blend of eastern Assamese, without too many distinctive eastern features, like /ɹ/ deletion, which is a robust phenomenon in the eastern varieties, is still considered to be the norm." (Mahanta 2012:217)

- ^ "Now, Dispur, the Capital city being around Guwahati, as also with the spread of literacy and education in the western Assam districts, forms of the Central and Western dialects have been creeping into the literary idiom and reshaping the standard language during the last few decades." (Goswami 2003:436)

- ^ "Assamese Association – of Australia (ACT & NSW)".

- ^ "Welcome to the Website of "Axom Xomaj",Dubai, UAE (Assam Society of Dubai, UAE)!".

- ^ "Constitution". Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ "AANA - AANA Overview".

- ^ "Secretariat Administration Department". assam.gov.in. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d Assamese Archived 28 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Resource Centre for Indian Language Technology Solutions, Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati.

- ^ (Mahanta 2012:220)

- ^ (Mahanta 2012:218)

- ^ "Assamese, alone among NIA languages except for Romany, has also lost the characteristic IA dental/retroflex contrast (although it is retained in spelling), reducing the number of articulations, with the loss also of /c/, to three." (Masica 1993, p. 95)

- ^ Moral 1997, p. 45.

- ^ The word "hare", for example: śaśka (OIA) > χɔhā (hare). (Masica 1993, p. 206)

- ^ Goswami, Upendranath (1970), A Study on Kamrupi, p.xiii /x/ does not occur finally in Kamrupi. But in St. Coll. it occurs. In non-initial positions O.I.A sibilants became /kʰ/ and also /h/ whereas in St. Coll. they become /x/.

- ^ B Datta (1982), Linguistic situation in north-east India, the distinctive h sound of Assamese is absent in the West Goalpariya dialect

- ^ Whereas most fricatives become sibilants in Eastern Goalpariya (sukh, santi, asa in Eastern Goalpariya; xukh, xanti, axa in western Kamrupi) (Dutta 1995, p. 286); some use of the fricative is seen as in the word xi (for both "he" and "she") (Dutta 1995, p. 287) and xap khar (the snake) (Dutta 1995, p. 288). The /x/ is completely absent in Western Goalpariya (Dutta 1995, p. 290)

- ^ Chatterjee, Suniti Kumar, Kirata Jana Krti, p. 54.

- ^ Moral 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Directionality and locality in vowel harmony: With special reference to vowel harmony in Assamese (Thesis) – via www.lotpublications.nl.

- ^ (Mahanta 2012:221)

- ^ (Sarma 2017:119)

- ^ Bora, Mahendra (1981). The Evolution of the Assamese Script. Jorhat, Assam: Asam Sahitya Sabha. pp. 5, 53. OCLC 59775640.

- ^ Hanif, N (2000). "Zulqad Ali, Sufi Shaheb Hazrad (d. 1891A.D.)". Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: South Asia. pp. 401–402.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights Assamese ()" (PDF). ohchr.org. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Kommaluri, Subramanian & Sagar K 2005.

- ^ Moral 1997, p. 47.

- ^ Moral 1997, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Moral 1997, p. 48.

- ^ "Assamese may be divided dialectically into Eastern and Western Assamese" (Kakati 1941, p. 16)

- ^ "Assamese:Its formation and development" – via Internet Archive.

- ^ (Goswami 2003:403)

- ^ Kakati 1941, p. 14-16.

- ^ Goswami 2003, p. 436.

- ^ a b c (Dutta 2003, p. 106)

- ^ Goswami 2003, pp. 439–440.

- ^ a b (Dutta 2003, p. 107)

- ^ (Dutta 2003, pp. 108–109)

References edit

- Chatterji (1926). The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language.

- DeLancey, Scott (2012). "On the Origin of Bodo-Garo". In Hyslop, Gwendolyn; Morey, Stephen; Post, Mark W. (eds.). Northeast Indian Linguistics. Vol. 4. pp. 3–20. doi:10.1017/UPO9789382264521.003. ISBN 978-93-82264-52-1.

- Dutta, Birendranath (1995). A Study of the Folk Culture of the Goalpara Region of Assam. Guwahati, Assam: University Publication Department, Gauhati University. ISBN 978-81-86416-13-6.

- Dutta, Birendranath (2003). "Non-Standard Forms of Assamese: Their Socio-cultural Role". In Miri, Mrinal (ed.). Linguistic Situation in North-East India (2nd ed.). Concept Publishing Company, New Delhi. pp. 101–110. ISBN 978-81-8069-026-6.

- Goswami, G. C.; Tamuli, Jyotiprakash (2003). "Asamiya". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge. pp. 391–443. ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7.

- Guha, Amalendu (December 1983). "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam (1228-1714)" (PDF). Social Scientist. 11 (12): 3–34. doi:10.2307/3516963. JSTOR 3516963.

- Kakati, Banikanta (1941). Assamese: Its Formation and Development. Gauhati, Assam: Government of Assam.

- Kakati, Banikanta (1953). "Assamese Language". In Kakati, Banikanta (ed.). Aspects of Early Assamese Literature. Gauhati University. pp. 1–16. OCLC 578299.

- Kar, Boddhisattva (2008). "'Tongue Has No Bone': Fixing the Assamese Language, c.1800–c.1930". Studies in History. 24 (1): 27–76. doi:10.1177/025764300702400102. S2CID 144577541.

- Khan, M. Siddiq (1962). "The Early History of Bengali Printing". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 32 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1086/618956. JSTOR 4305188. S2CID 148408211.

- Kommaluri, Vijayanand; Subramanian, R.; Sagar K, Anand (2005). "Issues in Morphological Analysis of North-East Indian Languages". Language in India. 5.

- Mahanta, Sakuntala (2012). "Assamese". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 42 (2): 217–224. doi:10.1017/S0025100312000096.

- Masica, Colin P (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Medhi, Kaliram (1988). Assamese Grammar and the Origin of Assamese Language. Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam. OCLC 22067340.

- Moral, Dipankar (1997). "North-East India as a Linguistic Area" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies. 27: 43–53.

- Neog, Maheshwar (1980). Anandaram Dhekiyal Phukan. New Delhi: Sahiyta Akademi. OCLC 9110997.

- Oberlies, Thomas (2007). "Chapter Five: Aśokan Prakrit and Pāli". In Cardona, George; Jain, Danesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Pattanayak, D. P. (2016). "Oriya and Assamese". In Emeneau, Murray B.; Fergusson, Charles A. (eds.). Linguistics in South Asia. De Gruyter. pp. 122–152. ISBN 978-3-11-081950-2.

- Saikia, Nagen (1997). "Assamese". In Paniker (ed.). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- Sarma, Parismita (2017). Analysis and building an unrestricted speech synthesizer with reference to assamese language (PhD). Gauhati University. hdl:10603/195592.

- Sharma, M. M. (1990). "Language and Literature". In Barpujari, H. K. (ed.). The Comprehensive History of Assam: Ancient Period. Vol. I. Guwahati, Assam: Publication Board, Assam. pp. 263–284. OCLC 25163745.

- Toulmin, Mathew W S (2006). Reconstructing linguistic history in a dialect continuum: The Kamta, Rajbanshi, and Northern Deshi Bangla subgroup of Indo-Aryan (PhD). The Australian National University.

- Toulmin, Mathew W S (2009). From Linguistic to Sociolinguistic Reconstruction: The Kamta Historical Subgroup of Indo-Aryan. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 978-0-85883-604-4.

External links edit

- Assamese language at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Axamiyaa Bhaaxaar Moulik Bisar by Mr Devananda Bharali (PDF)

- Candrakānta abhidhāna : Asamiyi sabdara butpatti aru udaharanere Asamiya-Ingraji dui bhashara artha thaka abhidhana. second ed. Guwahati : Guwahati Bisbabidyalaya, 1962.

- A Dictionary in Assamese and English (1867) First Assamese dictionary by Miles Bronson from (books.google.com)

- Assamese proverbs, published 1896