Summary

'Ayn Ghazal (Arabic: عين غزال, "Spring of the Gazelle") was a Palestinian Arab village located 21 kilometers (13 mi) south of Haifa. Depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War as a result of an Israeli military assault during Operation Shoter, the village was then completely destroyed. Incorporated into the State of Israel, it is now mostly a forested area. The Israeli moshav of Ofer ("fawn") was established in 1950 on part of the former village's lands. Ein Ayala, a moshav established in 1949, lies just adjacent; its name being the Hebrew translation of Ayn Ghazal.[6]

Ayn Ghazal

عين غزال 'Ain Ghazal, 'Ein Ghazal | |

|---|---|

Village | |

The Maqam (shrine) of Sheikh Shahada | |

| Etymology: "Spring of the gazelle"[1] | |

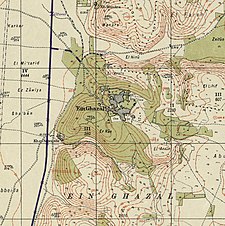

1870s map 1870s map  1940s map 1940s map modern map modern map  1940s with modern overlay map 1940s with modern overlay mapA series of historical maps of the area around Ayn Ghazal (click the buttons) | |

Ayn Ghazal Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°37′55″N 34°58′03″E / 32.63194°N 34.96750°E | |

| Palestine grid | 147/226 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Haifa |

| Date of depopulation | July 24–26, 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14,628 dunams (14.628 km2 or 5.648 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 2,170[2][3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Ein Ayala?[5]Ofer |

History edit

In 1517 the area of 'Ayn Ghazal was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Palestine. During the 16th and 17th centuries, it belonged to the Turabay Emirate (1517-1683), which encompassed also the Jezreel Valley, Haifa, Jenin, Beit She'an Valley, northern Jabal Nablus, Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe, and the northern part of the Sharon plain.[7][8]

In 1799, it appeared as the village Ain Elgazal on the map that Pierre Jacotin compiled that year, though it was misplaced.[9]

In 1870, Victor Guérin passed by, and noted that the village had 290 inhabitants. It was divided into two sections, and surrounded by tobacco plantations.[10]

Under Ottoman rule like much of the rest of Palestine in the late 19th century, Ayn Ghazal was described as a small village built of stone and mud, with about 450 residents. The villagers cultivated 35 Faddans of land (1 faddan is equal to 100-250 dunams).[11] Much of the land in the Ayn Ghazal and the neighbouring villages of Jaba', Khubiza, Tira, and Sarafand was owned by the sons of Abdel al-Latif al-Salah, who himself owned the entire village of Ji'ara. All these villages became entirely dependent upon the Salah family because of loans they took from them or as a result of the family's commercial activities.[12]

Ayn Ghazal had two schools: an elementary school for boys founded by the Ottomans in 1886, and an elementary school for girls. The village also had a cultural club and an athletic club.[13] The villagers were Muslim, and they maintained a Maqam (shrine) for a local sage named Sheikh Shahada.[13]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Ain Ghuzal had about 910 inhabitants; all Muslims,[14] while in the early twentieth century the number of inhabitants was given as 883, and a mosque and a school in the village was noted by travellers.[15]

British Mandate era edit

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, ‘Ain Ghazal had a population of 1,046, all Muslims,[16] increasing in the 1931 census, when it was counted with Khirbat al-Sawamir, to 1,439, still all Muslims, in 247 houses.[17]

In the 1945 statistics the population was 2,170, all Muslims,[2] and it had a total of 18,079 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[3] 1,486 dunams were for plantations and irrigable land, 8,472 for cereals,[18] while 130 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[13][19]

1948, and aftermath edit

When the conflict started, the village was poorly armed. Israeli intelligence estimated the village arsenal at a total of 87 weapons by mid-1947; including 23 obsolete rifles and 45 pistols.[20] The November 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine allocated Ayn Ghazal and other Arab villages in the Haifa district of Mandate Palestine to the proposed Jewish state, which alongside the Arab state, was to be established upon termination of the British Mandate, scheduled for May 15, 1948. Ayn Ghazal and the neighboring village of Ayn Hawd were attacked on the evening of April 11, 1948, according to the Palestinian newspaper Filastin, who reported that a group of 150 Jewish troops were unsuccessful in driving out the inhabitants.[21] Arab states responded to Israel's Declaration of Independence on May 15, 1948, by sending in Arab troops, kicking off the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. On May 20, the Associated Press reported that another attack on Ayn Ghazal and Ayn Hawd had been thwarted.[22]

In early June 1948, an Israel Defense Forces (IDF) report shows that Ayn Ghazal, together with Ijzim and Ja'ba, were asking the IDF, "to open negotiation for surrender." Nothing resulted from the request.[23] On 14 July, before the Second truce of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the Israeli cabinet discussed the three villages in "The Little Triangle". Ben-Gurion said that there was no need to hurry:

"these villages are in our pocket [...] We can act against them also after the [reinstitution of the] truce. This will be a police action... They are not regarded as enemy forces as their area is ours [i.e., in Israel] and they are inhabitants of the state...[and] these villages do not represent a military danger."[24]

The second truce, beginning on the 18 July, was not violated by the villagers.[25]

According to Meron Benvenisti, IDF actions over course of the Second Truce were concentrated on "cleansing" small clusters of Arab villages located in "strategic" areas.[26] 'Ayn Ghazal was depopulated along with two other villages (Ijzim and Ja'ba) located on the western slopes of the Carmel mountains between July 24 and 26.[26] A week after the start of the truce, Israel undertook Operation Shoter ("Operation Policeman"), with the aim of conquering the "Little Triangle" villages.[27] The operation was executed by a combination of brigades from the Israel Defense Forces and the military police.[26] On July 25, street fighting was reported from Ayn Ghazal and Ja'ba. On the morning of the next day, the villages were found deserted.[27]

'Ayn Ghazal was one of dozens of Palestinian villages subjected to aerial bombardment after the IDF managed to procure B-17 bombers and fighter planes from the European and American black markets during the First Truce (June–July 1948). Salah Abdel Jawad writes that in addition to loss of civilian life, the air raids spread, "widespread demoralisation due to its indiscriminate character, and because Palestinians who had never experienced aerial bombardment before, had no defences against it."[28] (Later, the then Israeli Foreign Minister Shertok lied to a United Nations mediator and said that "no planes were used".)[13][29]

Azzam Pasha, the Secretary General of the Arab League issued a statement alleging that atrocities were committed during and after the attacks. In particular it was stated that 28 people from al-Tira were burnt alive. The IDF rejected these allegations but admitted that their soldiers had found 25–30 bodies at 'Ayn Ghazal in "an advanced state of decomposition," and that the soldiers made prisoners bury the remains. The IDF also buried about 200 bodies found in the three villages after the battle.[30] On July 28, a United Nations observer visited the area, and found, according to Folke Bernadotte, "no evidence to support claims of massacre."[31] In early August, 1948, neighbouring Jewish settlers arrived in carts and looted Ayn Ghazal and Ja'ba.[32]

In mid-September 1948, UN investigators placed the number of killed or missing in the three villages (Ayn Ghazal, Ijzim and Ja'ba) at 130. Bernadotte condemned Israel's "systematic" destruction of Ayn Ghazal and Ja'ba, and asked that the Israeli government restore at its own expense all houses damaged or destroyed during and after the attack. Bernadotte said that a total of 8,000 people had been driven out of the three villages, and demanded that they be allowed to return; however, Israel rejected these demands.[13]

One of a number of Palestinian villages that was completely obliterated and then reforested by Israeli authorities, Ayn Ghazal, like Mujeidel, Ma'alul, and Mi'ar, was planted with pine or cypress trees.[33] After the area was incorporated into the State of Israel, the moshav of Ein Ayala was established in 1949 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) southeast of the village site. Benny Morris writes that it is close to village land;[5] however, Walid Khalidi writes that it is not on village land. The moshav of Ofer was established the following year 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) southeast of the built up portion of the village, and according to Khalidi, was built on village land.[13] Describing the village remains in 1992, Khalidi writes:

"The dilapidated shrine of Sheikh Shahada is the only standing structure on the village site. Ruins of walls and piles of stones can be seen all over the site, as well as stands of pine, cactus, and fig and pomegranate trees. The site has recently been fenced in for use as a grazing area. The flat lands around it are also used for growing vegetables, bananas, and other types of fruit. Parts of the slopes are planted with almond trees."[13]

Zochrot, an Israeli-Jewish organization that aims to raise awareness of the Nakba has produced a booklet on Ayn Ghazal and organized tours to the site of the destroyed village. The booklet was produced in collaboration with Ali Hamude, an Internally displaced Palestinian refugee from Ayn Ghazal, who currently lives in Furaydis. Hundreds of copies of the booklet were distributed by Hamude, and a village school in Furaydis uses the booklet during class trips to Ayn Ghazal to educate students on its history.[34]

References edit

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 142

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 13

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 47

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #166. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. xxii, settlement #118

- ^ Bronstein in Masalha, 2005, p. 233.

- ^ al-Bakhīt, Muḥammad ʻAdnān; al-Ḥamūd, Nūfān Rajā (1989). "Daftar mufaṣṣal nāḥiyat Marj Banī ʻĀmir wa-tawābiʻihā wa-lawāḥiqihā allatī kānat fī taṣarruf al-Amīr Ṭarah Bāy sanat 945 ah". www.worldcat.org. Amman: Jordanian University. pp. 1–35. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Marom, Tepper; Adams, Matthew, J (2023). "Lajjun: Forgotten Provincial Capital in Ottoman Palestine" (PDF). Levant. 55 (2): 218–241. doi:10.1080/00758914.2023.2202484. S2CID 258602184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 163 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guérin, 1875 p. 302

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 41. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p.148

- ^ Yazbak, 1998, p. 140

- ^ a b c d e f g Khalidi, 1992, p.148.

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 179

- ^ Mülinen, 1908, p. 284

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Haifa, p. 34

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 90.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 89

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 139

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 30

- ^ Filastin, 13.04.1948, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 150, cited in Slyomovics, 1998, p. 100

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 150, cited in Slyomovics, 1998, p. 100

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 96, 146. Note 172, logbook entry, IDF, for 9. June.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 438, 439, Note 146

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 441, note 169; citing the investigating "Central Truce Supervision Board", chaired by US Brigadier General W.E. Riley. This board also found that the IDF assault on the villages had been a violation of the truce.

- ^ a b c Benvenisti, 2000, p. 152.

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. 439

- ^ Salah Abdel Jawad in Benvenisti, 2007, p. 97

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 439, note 152

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 440, note 163 & 164

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 440, note 167. However, according to this note, "something amiss had indeed occurred", as it refers to an ongoing IDF "trial" concerning the "28". The relevant IDF files are still closed, according to Morris, 2004, p. 458.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 441, note 173.

- ^ Slyomovics, 1998, p. 30

- ^ Bronstein in Masalha, 2005, p. 220

Bibliography edit

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, E.; Gans, Chaim; Ḥanafī, Sārī (2007). Eyal Benvenisti; Chaim Gans; Sārī Ḥanafī (eds.). Israel and the Palestinian refugees (Illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-68160-1.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- Masalha, N., ed. (2005). Catastrophe Remembered: Palestine, Israel and the Internal Refugees. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-84277-622-3.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Mülinen, Egbert Friedrich von 1908, Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Karmels "Separateabdruck aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palëstina-Vereins Band XXX (1907) Seite 117-207 und Band XXXI (1908) Seite 1-258."

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Slyomovics, Susan (1998). The object of memory: Arab and Jew narrate the Palestinian village (Illustrated ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1525-0.

- Yazbak, M. (1998). Haifa in the late Ottoman period, 1864-1914: a Muslim town in transition (Illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11051-9.

External links edit

- Welcome To 'Ayn Ghazal

- 'Ayn Ghazal, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 8: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Ayn Ghazal from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- 3ein Ghazal Archived 2020-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, from Dr. Moslih Kanaaneh

- Ali Hamoudi, Ayn Ghazzal, testimony, 1 March 2003, from Zochrot

- Tour and signposting at Ayn Ghazzal, 6.6.03, Zochrot

- Remembering Ayn Ghazal, Booklet from Zochrot, 07/2003

- "Memoirs" "Refugee Interviews" in Journal of Palestine Studies:

- "Refugee Interviews" special feature in 18, no. 1 (Aut. 88): 158-71. Featuring testimonies of witnesses of the fall of Farradiyyah, Acre,`Ayn Ghazal, and Umm al-Fahm. pdf-file, downloadable