Summary

Bayt Dajan (Arabic: بيت دجن, romanized: Bayt Dajan; Hebrew: בית דג'ן), also known as Dajūn, was a Palestinian Arab village situated approximately 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) southeast of Jaffa. It is thought to have been the site of the biblical town of Beth Dagon, mentioned in the Book of Joshua and in ancient Assyrian and Ancient Egyptian texts. In the 10th century CE, it was inhabited mostly by Samaritans.

Bayt Dajan

بيت دجن Beit Dajan, Bait Dajan, Dajūn, Beit Dejan | |

|---|---|

![Bayt Dajan, before 1935. From the Khalil Raad-collection.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Bait_Dajan.jpg/200px-Bait_Dajan.jpg) Bayt Dajan, before 1935. From the Khalil Raad-collection.[1] | |

| Etymology: "The house of Dagon"[2] | |

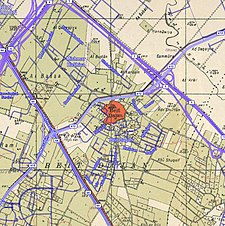

1870s map 1870s map  1940s map 1940s map modern map modern map  1940s with modern overlay map 1940s with modern overlay mapA series of historical maps of the area around Bayt Dajan (click the buttons) | |

Bayt Dajan Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 32°0′13″N 34°49′46″E / 32.00361°N 34.82944°E | |

| Palestine grid | 134/156 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jaffa |

| Date of depopulation | 25 April 1948[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17,327 dunams (17.327 km2 or 6.690 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 3,840[3] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Influence of nearby town's fall |

| Current Localities | Beit Dagan[6][7] Mishmar HaShiv'a[7] Hemed[7] Ganot[7] |

In the mid-16th century, Bayt Dajan formed part of an Ottoman waqf established by Roxelana, the wife of Suleiman the Magnificent, and by the late 16th century, it was part of the nahiya of Ramla in the liwa of Gaza. The villagers, who were all recorded as Muslim, paid taxes to the Ottoman authorities for property and agricultural goods and animal husbandry conducted in the villages, including the cultivation of wheat, barley, fruit, and sesame, as well as on goats, beehives and vineyards. In the 19th Century, the village women were also locally renowned for the intricate, high quality embroidery designs, a ubiquitous feature of traditional Palestinian costumes.

By the time of the Mandatory Palestine, the village housed two elementary schools, a library and an agronomic school. After an assault by the Alexandroni Brigade during Operation Hametz on 25 April 1948 in the lead up to the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, the village was entirely depopulated.[8] The Israeli town of Beit Dagan was founded at the same site in October 1948.[9]

Another Bayt Dajan, not to be confused with this one, is located southeast of Nablus.[10]

Etymology edit

Bayt Dajan /Bēt Dajan/ is a Canaanite name mentioned Both Standard Babylonian (in a Neo-Assyrian inscription from 701 BC) Bīt(É)-da-gan-na78 and [Bητ]οδεγανα on the Madaba map.[11]

History edit

Iron Age edit

The village has a millennium-long history. It is mentioned in Assyrian and Ancient Egyptian texts as "Bīt Dagana" and bet dgn, respectively.[12] Its Arabic name, Bayt Dajan, preserves its ancient name.[12]

Byzantine era edit

Jerome describes the village in the 4th century CE as "very large", noting its name then as "Kafar Dagon" or "Caphardagon", situating it between Diospolis (modern Lod) and Yamnia (Yavne/Yibna).[10][12] Bayt Dajan also appears on the 6th century Map of Madaba under the name [Bet]o Dagana.[12]

Early Islamic era edit

The nearby site of Khirbet Dajūn, a tel with ruins to the southwest of Bayt Dajan, preserves the Dagon rather than Dagan spelling.[12] In Arabic literature, there are many references to Dajūn, which was also used to refer to Bayt Dajan itself.[12][13]

During his reign of 724–743 CE, the Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik built a palace in Bayt Dajan with white marble columns.[14]

The Continuatio of the Samaritan Chronicle of Abu'l-Fath mentions a prominent Samaritan from Dajūn named Yosef ben Adhasi. When the governor ordered all dhimmis to display a wooden figure on their doors, he persuaded the authorities that Samaritans would use a menorah symbol.[15] In the 880s, a Samaritan named Ibn Adhasi, from the same prominent family in Dajūn, was accosted by the local governor, Abdullah Ibn al-Fatah, who demanded a large sum of money as blackmail and sought to punish him. Ibn Adhasi fled to the mountains, taking refuge in caves.[16]

Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi mentions in the 10th century, a road in the Ramla area, darb dajūn, as connecting to the town of Dajūn which had a Friday mosque, and in a separate entry he adds that most of the town's inhabitants were Samaritans. By this time, one of the eight gates to the city of Ramla was also named "Dajūn".[17][18][19]

In the 11th century, Bayt Dajan served as a headquarters for the Fatimid army in Palestine.[20]

Crusader and Ayyubid eras edit

During the Crusader period, Richard the Lionheart built a small castle in the village in 1191. Known as Casal Maen (or Casal Moein), it "was the utmost limit of inland occupation allowed [to the Crusaders] by Saladin," and was destroyed by Saladin following the signing of the Treaty of Jaffa on 2 September 1192.[12][21][22]

In 1226, during Ayyubid rule, Yaqut al-Hamawi writes that it was "one of the villages in the district of Ramla" and devotes the rest of his discussion of it to Ahmad al-Dajani, also known as Abu Bakr Muhammad, a renowned Muslim scholar who hailed from there.[12]

Ottoman era edit

During early Ottoman rule in Palestine, in 1552, 18.33 carats of the revenues of the village of Bayt Dajan weredesignated for the new waqf of Hasseki Sultan Imaret in Jerusalem, established by Hasseki Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana), the wife of Suleiman the Magnificent.[23] Administratively, the village belonged to the Sub-district of Ramla in the District of Gaza.[24]

In the 1596 tax records, Bayt Dajan was a village in the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Ramla, part of the Liwa of Gaza. It had a population of 115 Muslim households; an estimated 633 persons. The villagers paid taxes to the authorities for the crops that they cultivated, which included wheat, barley, fruit, and sesame as well as on other types of agricultural products, such as goats, beehives and vineyards; a total of 14,200 akçe. All of the revenue went to a waqf.[25]

In 1051 AH/1641/2, the Bedouin tribe of al-Sawālima from around Jaffa attacked the villages of Subṭāra, Bayt Dajan, al-Sāfiriya, Jindās, Lydda and Yāzūr belonging to Waqf Haseki Sultan.[26]

An Arabic inscription on marble dating to 1762 was found in Bayt Dajan. Held in the private collection of Moshe Dayan, Moshe Sharon identified it as a dedicatory inscription for a Sufi maqam for a popular Egyptian saint, Ibrahim al-Matbuli, who was buried in Isdud.[12] The village appeared as a village on the map of Pierre Jacotin compiled in 1799, though it was wrongly named as Qabab.[27]

In 1838 Beit Dejan was among the villages Edward Robinson noted from the top of the White Mosque, Ramla.[28] It was further noted as a Muslim village, in the Lydda District.[29] A headstone, made of limestone with a poetic inscription in Arabic from Bayt Dajan, dating to 1842, was also in Dayan's private collection.[12]

Socin found from an official Ottoman village list from about 1870 that Bayt Dajan had a population of 432, with a total of 184 houses, though the population count included men, only.[30] Hartmann found that Bet Dedschan had 148 houses.[31]

In the late 19th century, Bayt Dajan was described as moderate-sized village surrounded by olive trees.[32] Philip Baldensperger noted of Bayt Dajan in 1895 that:

The inhabitants are very industrious, occupied chiefly in making mats and baskets for carrying earth and stones. They own camels for carrying loads from Jaffa to Jerusalem, cultivate the lands, and work at building etc., in Jaffa or on the railway works. The women flock every day to Jaffa and on Wednesday to Ramla—to the market held there, with chickens, eggs and milk.[33]

In 1903, a cache of gold coins were found in Khirbet Dajun by villagers from Bayt Dajan, who used this site as a quarry. The discovery prompted R. A. Macalister to visit the site. Based on his observations detailed in a report for the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF), Macalister suggests a continuity in settlement over the historical phases in Bayt Dajan's development :

"Thus we have three epochs in the history of Beth-Dagon — the first on an as yet unknown site, from the Amorite to the Roman periods; the second at Dajiin, extending over the Roman and early Arab periods; the third at the modern Beit Dejan, lasting to the present day. It is probable that the present population could, had they the necessary documents, show a continuous chain of ancestry extending from the first city to the last."[34]

British Mandate era edit

By the 20th century, the village had two elementary schools, one for boys, and one for girls. The school for boys was established during the British Mandate in Palestine in 1920. It housed a library of 600 books and had acquired 15 dunams of land that were used for instruction in agronomy.[35]

In the 1922 census of Palestine, Bait-Dajan had a population of 1,714 residents, all Muslims[36] increasing the 1931 census to 2,664; 2,626 Muslims, 27 Christians and 11 Jews, in a total of 591 houses.[37]

In 1934, when Fakhri al-Nashashibi established the Arab Workers Society (AWS) in Jerusalem, an AWS branch was also opened in Bayt Dajan.[38] By 1940, 353 males and 102 females attended the schools.[35]

In the 1945 statistics the population was 3,840; 130 Christians and 3,710 Muslims,[3] while the total land area was 17,327 dunams.[5] Of this, a total of 7,990 dunams of land was used for citrus and banana cultivation, 676 dunams for cereals and 3,195 dunams were irrigated or used for orchards,[35][39] while 14 dunams were classified as built-up areas.[40]

1948 Palestine War edit

The village of Bayt Dajan was depopulated in the weeks leading up to the 1948 Arab–Israeli war, during the Haganah's offensive Mivtza Hametz (Operation Hametz) on 28–30 April 1948. This operation was held against a group of villages east of Jaffa, including Bayt Dajan. According to the preparatory orders, the objective was to "opening the way [for Jewish forces] to Lydda". Though there was no explicit mention of the prospective treatment of the villagers, the order spoke of "cleansing the area" [tihur hashetah].[41] The final operational order stated: "Civilian inhabitants of places conquered would be permitted to leave after they are searched for weapons."[42] On the 30 April, it was reported that the inhabitants of the Bayt Dajan had left, and that Iraqi irregulars had moved into the village.[43]

Bayt Dajan was one of at least eight villages destroyed by Israel's First Transfer Committee between June and July 1948 under the leadership of Joseph Weitz.[44][45] On 16 June 1948, David Ben-Gurion, almost certainly based on a progress report from Weitz, noted Bayt Dajan as one of the Palestinian villages that they had destroyed.[46] On 23 September 1948 General Avner named Bayt Dajan as a suitable village for resettlement for new Jewish immigrants (olim) to Israel.[47]

Israel edit

Following the war the area was incorporated into the State of Israel. Four villages, Beit Dagan (established six months after the conquest), Mishmar HaShiv'a (1949), Hemed (1950) and Ganot (1953) were later established on land that had belonged to the Bayt Dajan.[7]

The Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the village in 1992: "A number of houses remain; some are deserted, others are occupied by Jewish families, or used as stores, office buildings, or warehouses. They exhibit a variety of architectural features. One inhabited house is made of concrete and has a rectangular plan, a flat roof, rectangular front windows, and two arched side windows. Another has been converted into the Eli Cohen synagogue; it is made of concrete and has a flat roof and a round-arched front door and window. Stars of David have been painted on its front door and what appears to be a garage door. One of the deserted houses is made of concrete and has a gabled, tiled roof that is starting to collapse; others are sealed and stand amid shrubs and weeds. Cactuses and cypress, fig, and date palm trees grow on the site. The land in the vicinity is cultivated by Israelis."[7]

Demographics edit

During early Ottoman rule in 1596, there were 633 inhabitants in Bayt Dajan.[25] In the 1922 British Mandate census, the village had 1,714 residents,[36] rising to 2,664 in 1931.[37] There were 591 houses in the latter year.[48] Sami Hadawi counted a population of 3,840 Arab inhabitants in his 1945 land and population survey.[5] From the 4th century CE to the 10th century, Samaritans populated Bayt Dajan.[48] In 1945, Most of the inhabitants were Muslims, but a Christian community of 130 also existed in the village.[35] Palestinian refugees amounted to 27,355 people in 1998.[8]

Culture edit

Philip J. Baldensperger noted in 1893: "At Beit Dejan I copied the following marks or drawings with which the houses are ornamented. The woman of the house generally paints them in whitewash. I was given the following signification:"[49] "They also very often print hands on the doors, by dipping their own into whitewash, and pressing them against the door. They very often mark with henna at the feasts the door-posts of the Makam or Wely."[50]

Bayt Dajan was known to be among the wealthiest communities in the Jaffa area, and their embroideresses were reported to be among the most artistic.[51] A center for weaving and embroidery, it exerted influences on many other surrounding villages and towns. Costumes from Beit Dajan were noted for their varied techniques, many of which were adopted and elaborated from other local styles.[52]

White linen garments inspired by Ramallah styles were popular, using patchwork and appliqued sequins in addition to embroidery.[52] A key motif was the nafnuf design: a floral pattern thought to be inspired by the locally grown orange trees.[52] The nafnuf design evolved after World War I into embroidery running down the dress in long panels known as "branches" (erq). This erq style was the forerunner of the "6 branch" style dresses worn by Palestinian women in different regions today.[52] In the 1920s, a lady from Bethlehem named Maneh Hazbun came to live in Bayt Dajan after her brother bought some orange groves there. She introduced the rashek (couching with silk) style of embroidery, a local imitation of the Bethlehem style.[53]

The jillayeh (the embroidered outer garment for wedding costume) used in Bayt Dajan was quite similar to those of Ramallah. The difference was in decoration and embroidery. Typical for Bayt Dajan would be a motif consisting of two triangles, mirror-faced, with or without an embroidered stripe between them, and with inverted cypresses at the edges.[54] A jillayeh from Bayt Dajan (c. 1920s) is exhibited at the British Museum. The caption notes that the dress would be worn by the bride at the final ritual of wedding week celebrations, a procession known as 'going to the well'. Accompanied by all the village women in their finest dress, the bride would go to the well to present a tray of sweets to the guardian of the well and fill her pitcher with water to ensure good fortune for her home.[55] There are also several items from Bayt Dajan and the surrounding area is in the Museum of International Folk Art (MOIFA) collection at Santa Fe, United States.[54]

Artistic representations edit

Palestinian artist Sliman Mansour made Bayt Dajan the subject of one of his paintings. The work, named for the village, was one of a series of four on destroyed Palestinian villages that he produced in 1988; the others being Yalo, Imwas and Yibna.[56]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, pp. 231, 605, 606

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 213

- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 27

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xviii, village #219. Also gives cause(s) of depopulation.

- ^ a b c Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 52.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. xxi, Settlement #91.

- ^ a b c d e f Khalidi, 1992, p. 238

- ^ a b "Welcome to Bayt Dajan". Palestine Remembered. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ Gelber, 2006, p. 394.

- ^ a b Smith, 1854, p. 396.

- ^ Marom, Roy; Zadok, Ran (2023). "Early-Ottoman Palestinian Toponymy: A Linguistic Analysis of the (Micro-)Toponyms in Haseki Sultan's Endowment Deed (1552)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 139 (2).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sharon, 1999, p.89-p90.

- ^ Wheatley, 2000, p. 486.

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Levy-Rubin, Milka (2002). "The Samaritans during the Early Muslim Period according to the Continuatio to the Chronicle of Abu 'l-Fath". In Stern, Ephraim; Eshel, Hanan (eds.). The Samaritans (in Hebrew). Yad Ben-Zvi Press. p. 575. ISBN 965-217-202-2.

- ^ Levy-Rubin, Milka (2002). "The Samaritans during the Early Muslim Period according to the Continuatio to the Chronicle of Abu 'l-Fath". In Stern, Ephraim; Eshel, Hanan (eds.). The Samaritans (in Hebrew). Yad Ben-Zvi Press. p. 578. ISBN 965-217-202-2.

- ^ Levy, 1995, p. 492.

- ^ Al-Muqaddasi, 1886, p. 33

- ^ Conder, 1876, p.196

- ^ Gil and Broido, 1997, p. 727.

- ^ Stubbs and Hassall, 1902, p. 364

- ^ Ambroise et al., 2003, p. 125.

- ^ Singer, 2002, p. 50

- ^ Marom, Roy (2022-11-01). "Jindās: A History of Lydda's Rural Hinterland in the 15th to the 20th Centuries CE". Lod, Lydda, Diospolis. 1: 8.

- ^ a b Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 155. Quoted in Khalidi 1992, p. 237

- ^ Marom, Roy (2022-11-01). "Jindās: A History of Lydda's Rural Hinterland in the 15th to the 20th Centuries CE". Lod, Lydda, Diospolis: 13-14.

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 171 Archived 2019-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, p. 30

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, 2 appendix, p. 121

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 145

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 138

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 251. Cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 237.

- ^ Weir, p. 207, citing Philip Baldensperger (1895): "Beth-Dejan", in Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly, p. 114 ff.

- ^ Macalister, 1903, p. 357

- ^ a b c d Khalidi, 1992, p. 237

- ^ a b Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jaffa, p. 20

- ^ a b Mills, 1932, p. 13.

- ^ Matthews, 2006, p. 228.

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 95

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 145

- ^ HGS\Operations to Alexandroni, etc., "Orders for Operation "Hametz", 26 Apr. 1948. IDFA 6647\49\\15. Cited in Morris, 2004, p. 217, 286

- ^ Operation Hametz HQ to Givati, etc., 27 Apr. 1948, 14:00 hours, IDFA 67\51\\677. See also Alexandroni to battalions, 27 Apr. 1948, IDFA 922\75\\949. Cited in Morris, 2004, p. 217, 286

- ^ 54th Battalion to Givati, "Subject: Summary for 29.4.48", 30 Apr. 1948, IDFA 1041\49\\18. Cited in Morris, 2004, pp. 176, 269

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 314

- ^ Fischbach, 2003, p. 14

- ^ Entry for 16 June 1948, DBG-YH II, 523–24. Cited in Morris, 2004, pp. 350, 398

- ^ Protocol of Meeting of Military Government Committee, 23 Sep. 1948, ISA FM 2564\11. Cited in Morris, 2004, pp. 394, 413

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, p. 236.

- ^ a b Baldensperger, 1893, p. 216

- ^ Baldensperger, 1893, p. 217

- ^ Jane Waldron Grutz (January–February 1991). "Woven Legacy, Woven Language". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ a b c d "Palestine costume before 1948: by region". Palestine Costume Archive. Archived from the original on 2002-09-13. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ Weir, 1989, pp. 225, 227.

- ^ a b Stillman, 1979, pp. 66, 67.

- ^ "Explore - Highlights: Coat dress". British Museum. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Ankori, 2006, p. 82.

Bibliography edit

- Ambroise; Ailes, Marianne; Barber, M. (2003). The history of the Holy War: Ambroise's Estoire de la guerre sainte (Illustrated ed.). by Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-001-6.

- Ankori, G. (2006). Palestinian Art. Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-259-4.

- Baldensperger, Philip J. (1893-07-01). "Peasant Folklore of Palestine". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 25 (3): 203-219.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, C. (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Dayan, Ayelet; Eshed, Vered (2012-12-31). "Bet Dagan" (124). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Fischbach, Michael R. (2012). Records of dispossession: Palestinian refugee property and the Arab–Israeli conflict (Illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12978-7.

- Gelber, Y. (2006). Palestine, 1948: war, escape and the emergence of the Palestinian refugee problem (2nd, illustrated ed.). Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-075-0.

- Gil, M.; Broido, Ethel (1997). A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Gorzalczany, Amir; Jakoel, Eriola (2013-12-11). "Bet Dagan" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Jakoel, Eriola; Nagar, Yossi (2014-07-13). "Bet Dagan, Ha-Havazzelet St" (126). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-22. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Levy, T.E. (1995). The archaeology of society in the Holy Land (Illustrated ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7185-1388-7.

- Macalister, R.A.S. (1903). "Dajun and Beth-Dagon and the transference of Biblical place- names". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 35 (4): 356–358. doi:10.1179/peq.1903.35.4.356.

- Marcus, Jenny (2011-04-18). "Bet Dagan Es-Sitt Nafisa" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Matthews, Weldon C. (2006). Confronting an empire, constructing a nation: Arab nationalists and popular politics in mandate Palestine (Annotated ed.). I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-173-1.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Mukaddasi (1886). Description of Syria, including Palestine. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rauchberger, Lior (2008-04-03). "Bet Dagan" (120). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Rajab, J. (1989). Palestinian Costume. Indiana University. ISBN 0-7141-2517-2.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Sharon, M. (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B-C. Vol. 2. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11083-6. (Bayt Dajan pp. 89–93)

- Singer, A. (2002). Constructing Ottoman Beneficence: An Imperial Soup Kitchen in Jerusalem. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5352-9.

- Smith, W. (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman geography. Little, Brown & Co.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (1979). Palestinian Costume and Jewelry. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0490-7.

- Stubbs, W.; Hassall, Arthur (1902). Historical Introductions to the Rolls Series. Collected and Edited by Arthur Hassall. Adamant Media Corporation.

- Weir, Shelagh (1989). Palestinian Costume. British Museum Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-7141-2517-2. Exhibition catalog; see also chapters five and six (p. 203–270) on "Changing Fashions in Beit Dajan" and "Wedding Rituals in Beit Dajan".

- Wheatley, P. (2000). The places where men pray together: cities in Islamic lands, seventh through the tenth centuries (Illustrated ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-89428-7.

- Yannai, Eli (2008-08-24). "Bet Dagan" (120). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Yechielov, Stella (2013-05-23). "Bet Dagan" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading edit

- Widad Kawar/Shelagh Weir: Costumes and Wedding Customs in Bayt Dajan

External links edit

- Palestine Remembered – Bayt Dajan

- Bayt Dajan, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Coat dress, in British Museum