Summary

Beach Red is a 1967 World War II film starring Cornel Wilde (who also directed and produced) and Rip Torn. The film depicts a landing by the United States Marine Corps on an unnamed Japanese-held Pacific island. The film is based on Peter Bowman's 1945 novella of the same name, which was based on his experiences with the United States Army Corps of Engineers in the Pacific War.

| Beach Red | |

|---|---|

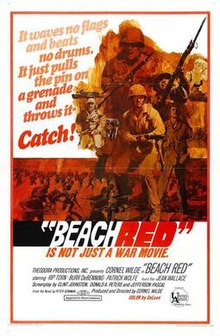

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Cornel Wilde |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Beach Red 1945 novel by Peter Bowman[1] |

| Produced by | Cornel Wilde |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Cecil Cooney |

| Edited by | Frank P. Keller |

| Music by | Antonio Buenaventura |

| Color process | DeLuxe Color |

Production companies | Theodora Productions, Inc. |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | August 3, 1967 |

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Title edit

During the Allied amphibious operations in World War II, designated invasion beaches were given a codename by color, such as "Beach Red," "Beach White," "Beach Blue", etc.[2] There was a "Beach Red" on virtually every assaulted island, in accordance with the standard beach designation hierarchy.

Plot edit

The 30-minute opening sequence of the film depicts an opposed beach landing. Its graphic depiction of the violence and savagery of war was echoed years later in Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan.[3] In one scene during the landing, a Marine is shown with his arm blown off, similar to Thomas C. Lea III's 1944 painting The Price.

As Americans are shown consolidating their gains, flashbacks illustrate the lives of American and Japanese combatants. Shifting first-person voice-over in a stream-of-consciousness style is also used to portray numerous characters' thoughts. Like Wilde's previous production of The Naked Prey (1965), the film does not use subtitles for characters speaking Japanese.

The film contains large sections of voice-over narration, often juxtaposed with still photographs of wives, etc. (who are anachronistically dressed in 1967 attire). Many soldiers in the film shed tears, and the narrative displays an unusual amount of sympathy for the enemy.[citation needed]

In one scene, an injured Cliff is lying close to an injured Japanese soldier in a scene paralleling the one from All Quiet on the Western Front with Paul Bäumer and Gérard Duval. Just after the two soldiers bond, other Marines appear and kill the Japanese soldier, distressing Cliff.

Director, producer, and co-writer Wilde plays a Marine captain, the company commander. Rip Torn plays his company gunnery sergeant, who utters the film's tagline, "That's what we're here for. To kill. The rest is all crap!"

Cast edit

- Cornel Wilde - Captain MacDonald

- Rip Torn - Gunnery Sergeant Honeywell

- Burr DeBenning - Egan

- Patrick Wolfe - Cliff

- Jean Wallace - Julie

- Jaime Sánchez - Colombo

- Dale Ishimoto - Captain Tanaka

Production edit

Beach Red was filmed on location in the Philippines using troops of the Philippine Armed Forces. The sequence of the Japanese dressed in Marine uniforms was inspired by Bowman's book, which mentions Japanese wearing American helmets to infiltrate American lines.[4] There were no incidents in the Pacific where large numbers of Japanese donned American uniforms and attempted to infiltrate a beachhead. The action, though, is similar in some ways to a large-scale Japanese counterattack and banzai charge conducted on July 7, 1944, on Saipan, which was defeated by U.S. Army troops with heavy losses.

When seeking assistance from the U.S. Marine Corps, Wilde was told that due to the commitments of the Vietnam War, all the Corps could provide the film was color stock footage taken during the Pacific War. The film provided had deteriorated, so Wilde had to spend a considerable part of the film's budget to restore the film to an acceptable quality in order to blend into the film. The Marine Corps was grateful that their historical film had been restored at no cost to them.[5]

The film's title sequence incorporates various paintings that suddenly segue into the preparations for the landing.

Soundtrack edit

The film's single musical theme is by Col. Antonino Buenaventura, a National Artist of the Philippines in Music. It appears in the title sequence, sung in a folk song manner by Jean Wallace – Wilde's wife – and appears in various other orchestrations throughout the film. Wallace also appears in flashback photos as Wilde's character's wife, Julie MacDonald.

Reception edit

Howard Thompson of The New York Times praised the film as "an admirable war movie that says a bit and suggests even more, thanks to Cornel Wilde."[6] Variety wrote that "[i]n contrast to many professedly anti-war films, Beach Red [sic] is indisputably sincere in its war is hell message."[7] In a capsule review published many years after the film debuted, Time Out London wrote, "Wilde's neglected WWII movie is an allegory about the futility and the carnage of Vietnam. ... The movie is massively and harrowingly brutal, almost like a horror movie, with severed limbs washing up on the beach. Although Wilde deals exclusively in pacifist clichés, the film has a genuine primitive power; in fact, it's the equal of anything made by Fuller."[8]

Awards edit

Beach Red received a 1968 Academy Award nomination for Best Film Editing.[7]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ "Beach Red". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Newell, Reg Pacific Star: 3NZ Division in the South Pacific in World War II Exisle Publishing, 1 Oct 2015

- ^ Basinger, Jeanine. "Translating War: The Combat Film Genre and Saving Private Ryan," Perspectives on History: the Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association (October 1998).

- ^ Bowman, Peter. Beach Red: A Novel (Random House, 1945).

- ^ p.203 Suid, Lawrence H. Guts & Glory: The Making of the American Military Image in Film University Press of Kentucky, 2002.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (August 4, 1967). "Screen: Strong War Film:Cornel Wilde's 'Beach Red' Opens Here". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Beach Red". Variety. December 31, 1966. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ ATU. "Beach Red". Time Out London. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

External links edit

- Beach Red at IMDb

- Beach Red at AllMovie

- Beach Red at the TCM Movie Database

- Beach Red at the American Film Institute Catalog