Summary

Bertram Raoul Bulkin (July 20, 1929 – March 10, 2012) was an American aeronautical engineer who participated in the first United States photo-reconnaissance satellite programs and is best known for his role in building the Hubble Space Telescope.

Bertram (Bert) R. Bulkin | |

|---|---|

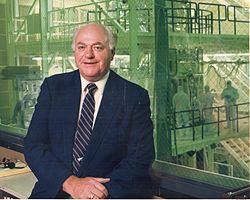

Bert Bulkin in front of Hubble Space Telescope assembly, 1989 | |

| Born | July 20, 1929 |

| Died | March 10, 2012 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Awards | Pioneer of Space Technology (CIA; 1985) Distinguished Public Service Award (NASA; March 21, 1991) Lodi Hall of Fame |

| Space career | |

| Aeronautical Engineer | |

Biography edit

Early life and education edit

Bulkin was born in Brooklyn, New York, the son of David Bulkin and Anne Clara Strauss,[1][2] both immigrants. He was named after Berel Reven Bulkin, a paternal uncle from the Kiev area of Ukraine. After residing briefly in Springfield, Massachusetts, he and his family returned to Brooklyn, where he attended P.S. 197, an elementary school. Bulkin was graduated from John Marshall High School (Los Angeles, California) in 1946 at age 16.[2] He then attended the University of California, Los Angeles, where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering.[2] During his time at UCLA, he took a summer job with what was then called Lockheed's[2] Advanced Development Projects facility, also known as the Skunk Works, located in Burbank, California.

Career edit

Bulkin began his career as a detail draftsman for Lockheed's[2] Skunk Works in Burbank, incorporating sketches of electrical or other systems into master blueprints for airplanes. Between 1951 and 1959, he contributed to electrical and armament systems design on programs including the P-2 Neptune and the Electra. In February 1954, he filed for a patent for an internally illuminated knob that could be used as part of an onboard aircraft warning system; that patent was granted in December 1956.[3] By 1957, he was working as a design engineer.[2] He then took a job with Hiller Helicopters in Palo Alto, California, which provided cover for the then-classified Corona program, the first U.S. photo-reconnaissance satellite.[4] In support of that program, he and William Williamson from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed a SECOR (Sequential Correlation of Range) spacecraft based on the OSCAR (Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio) model.[5] Bulkin's colleagues also credited him with proposing the use of ping-pong balls to cool the interior of one satellite module. Corona lore includes the story of another colleague stopped by the California Highway Patrol while driving from the Bay Area to a launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base, unable to explain the cases of ping-pong balls he was transporting in the back of his Ford Thunderbird.

After completing a management course with the Lockheed Management Institute at Santa Clara University in 1965, he became the payload integration manager for the Hexagon,[6] another early satellite reconnaissance program; he served as division manager for experiment design and integration for the Satellite Control Section,[7] a satellite launch vehicle development program in support of the Hexagon, until at least July 1970. From then until 1972, he was the director of advanced project development for the electro-optical division of International Telephone and Telegraph in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

On his return to Lockheed's Sunnyvale location, he was assigned to the company's proposal to build the Support Systems Module or basic spacecraft for the Space Telescope or Large Space Telescope (ST or LST; later renamed the Hubble Space Telescope or HST). Early on, observers noted the design continuity between the systems modules for the Hexagon and the LST.[8] After Lockheed won that contract in October 1977, Bulkin initially managed the equipment section. Lockheed became responsible for the physical integration of all systems aboard the HST.

In 1982, Bulkin was named Program Manager for the LST and was recognized for his leadership role on the program.[9] In that role, he accompanied senior Lockheed officials to hearings before the House of Representatives' Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications on June 16, 1983, and took several questions from the panel on cost, schedule, and performance concerns related to the telescope project.[10]

In January 1985, Robert W. Smith of NASA's Space Telescope History Project interviewed Bulkin, who reviewed several of the design and management issues that had arisen to that time.[11] The disaster that engulfed the Space Shuttle Challenger led to a review of the entire space-shuttle program, delaying the launch of the Hubble from 1986 to 1990.

Bulkin described the April 24, 1990 launch of the Hubble Space Telescope as "like watching your mother-in-law go over a cliff in your brand-new Cadillac." Asked at the time of the launch what scientists hoped to see with the new instrument, he said simply, "God."

On July 10, 1990, Bulkin appeared along with representatives of other companies contributing to the Hubble before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.[12] He appeared as Lockheed's Director of Scientific Space Programs to respond to Congressional concerns about flaws discovered in the Optical Telescope Assembly prepared for the HST by Hughes-Danbury (Perkin Elmer).

Bulkin also oversaw Lockheed's contributions to the Spitzer Space Telescope or Space Infrared Telescope Facility (launched 2003), the Gravity Probe B or Einstein Experiment (launched 2004), the Solar Probe (projected for 2018), and the ongoing Mission to Planet Earth, a NASA program proposed by physicist and astronaut Sally Ride in the 1987 Ride Report to improve the prediction of Earth's climate, weather, and natural hazards. He retired as Lockheed's Director of Scientific Space Programs in 1992 [2] but continued to support national space programs in an advisory capacity.

Scientific advisory work edit

As director emeritus of scientific space programs for Lockheed, Bulkin served on several national scientific advisory committees, including panels for three of the four space telescopes in NASA's Great Observatories Program: the Hubble, the Chandra, and the Spitzer.

• NRC Committee on Engineering Challenges to the Long-Term Operation of the International Space Station (1998-2000)

• External Independent Readiness Review Board for the Chandra Telescope

• Committee on the Engineering Challenges to the Long-Term Operation of the International Space Station[13]

• Independent Review Team for the Lyman-Spitzer Infrared Telescope

• Assessment of Options for Extending the Life of the Hubble Space Telescope (2004) [14]

Death edit

Bulkin died of complications from a heart attack at Lodi Memorial Hospital on March 10, 2012,[2] surrounded by children and several grandchildren. He is survived by his widow Margaret (Reed) Talbot Bulkin. He was preceded in death by his first wife Bernice (Horn) Willers, his later wife Carolyn Lee (Walker) Bulkin, his parents, and his sister Shirley (Bulkin) Katz Livingston.[2] H In 2012, Bulkin's name was inscribed on the National Air and Space Museum's Wall of Honor at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.[15]

Awards edit

Pioneer of Space Technology (for work on the Corona project) (CIA; 1985)

Distinguished Public Service Award (NASA; March 21, 1991)

Lodi Hall of Fame (Lodi, California; 2008)[16]

References edit

- ^ Bulkin, Bernard. "Bulkin family tree". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hanner, Rich (2012). "Space pioneer Bert Bulkin dies at 82". Lodi News-Sentinel. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Bulkin, Bertram R. "Internally Illuminated Knob". patent number 2775686. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ McDonald, Robert (1995). "CORONA: Success for Space Reconnaissance; A Look into the Cold War, and a Revolution for Intelligence" (PDF). Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing, Vol 61, No. 6, June 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Welch, Guy F. (December 1982). Hexagon (KH-9) Mapping Camera Program and Evolution (PDF). Office of the Secretary of the Air Force. p. 81. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Araki, Sam; Treat, Steve (Spring 2012). "Hexagon: No Single Failure Shall Abort the Mission: Managing System Integration for the NRO's Wide-Area Search Satellite from the Lockheed Missile and Space Company's Perspective" (PDF). National Reconnaissance: Journal of the Discipline and Practice (2012–U1): 88. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. (February 7, 2011). "The flight of the Big Bird: The origins, development, and operations of the KH-9 HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite". The Space Review. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ Huntsville (Alabama) Times, science editor Dave Dooling

- ^ Boyne, Walter J. (1998). Beyond the Horizons: the Lockheed Story (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 308. ISBN 0-312-19237-1.

- ^ U.S. Congress (1983). "Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications of the Committee on Science and Technology of the U.S. House of Representatives, 98th Congress" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Kahn, Mark (1985). "National Air and Space Archives, Space Telescope History Project, Accession No. 1999-0035" (PDF). National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ C-SPAN (10 July 1990). "Hubble Space Telescope Problems (see 2:04:00 and following)". Retrieved September 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Commission on Engineering and Technical Systems (CETS) (2000). "Engineering Challenges to the Long-Term Operation of the International Space Station". National Academies Press.

- ^ Committee on the Assessment of Options for Extending the Life of the Hubble Space Telescope, National Research Council of the National Academies (2005). "Assessment of Options for Extending the Life of the Hubble Space Telescope: Final Report". National Academies Press.

- ^ National Air and Space Museum. "Wall of Honor". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Bauserman, Pam (2008). "Lodi Hall of Fame (Lodi, California; 2008)". Lodi News-Sentinel. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

External links edit

- Farrow, Ross (2004). "'Father' of Hubble laments decision to end space telescope program". Lodi News-Sentinel. Retrieved January 30, 2004.