Summary

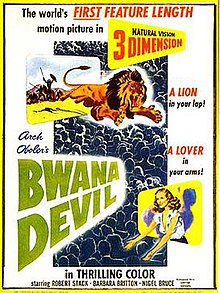

Bwana Devil is a 1952 American adventure B movie written, directed, and produced by Arch Oboler, and starring Robert Stack, Barbara Britton, and Nigel Bruce.[3][4][5] Bwana Devil is based on the true story of the Tsavo maneaters and filmed with the Natural Vision 3D system.[5] The film is notable for sparking the first 3D film craze in the motion picture industry, as well as for being the first feature-length 3D film in color and the first 3D sound feature in English.

| Bwana Devil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Arch Oboler |

| Written by | Arch Oboler |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | John Hoffman |

| Music by | Gordon Jenkins |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 79 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $323,000[2] |

| Box office | $5 million[2] |

The advertising tagline was: "The Miracle of the Age!!! A LION in your lap! A LOVER in your arms!"

Plot edit

The film is set in British East Africa in the early 20th century. Thousands of workers are building the Uganda Railway, Africa's first railroad, and intense heat and sickness make it a formidable task. Two men in charge of the mission are Bob Hayward and Dr. Angus McLean. A pair of man-eating lions are on the loose and completely disrupt the undertaking. Hayward desperately attempts to overcome the situation, but the slaughter continues.

Britain sends three big-game hunters to kill the lions. With them comes Bob's wife. After the game hunters are killed by the lions, Bob sets out once and for all to kill them. A grim battle between Bob and the lions endangers both Bob and his wife. Bob kills the lions and proves that he is not a weakling.

Cast edit

- Robert Stack as Bob Hayward

- Barbara Britton as Alice Hayward

- Nigel Bruce as Dr. Angus McLean

- Ramsay Hill as Major Parkhurst

- Paul McVey as commissioner

- Hope Miller as Portuguese girl

- John Dodsworth as Sir William Drayton

- Patrick O'Moore as Ballinger

- Pat Aherne as Latham

- Edward C. Short

- Bhogwan Singh as Indian Headman

- Paul Thompson

- Bhupesh Guha as the dancer

- Bal Seirgakar as Indian hunter

- Kalu K. Sonkar as Karparim

- Miles Clark Jr as Mukosi

Historic background edit

The plot was based on a well-known historical event, that of the Tsavo maneaters, in which many workers building the Uganda Railway were killed by lions. These incidents were also the basis for the book The Man-eaters of Tsavo (1907), the story of the events as written by Lt. Col. J. H. Patterson, the British engineer who killed the animals. The story was also the basis for the film The Ghost and the Darkness (1996) with Michael Douglas and Val Kilmer.

Natural Vision 3D Film Process edit

By 1951 film attendance had fallen dramatically from 90 million in 1948 to 46 million. Television was seen as the culprit and Hollywood was looking for a way to lure audiences back. Cinerama had premiered on September 30, 1952, at the Broadway Theater in New York and was a success there, but its bulky and expensive three-projector system and huge curved screen were impractical, if not impossible, to duplicate in any but the largest theaters.

Former screenwriter Milton Gunzburg and his brother Julian thought they had a solution with their Natural Vision 3D film process. They shopped it around Hollywood. 20th Century Fox was focusing on the introduction of CinemaScope and had no interest in another new process. Both Columbia and Paramount passed it up.

Only John Arnold, who headed the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer camera department, was impressed enough to convince MGM to take an option on it, but they quickly let the option lapse. Milton Gunzburg turned his focus to independent producers and demonstrated Natural Vision to Arch Oboler, producer and writer of the popular Lights Out radio show. Oboler was impressed enough to option it for his next film project.

Oboler said he had overheard Joseph Biroc and the camera crew talking about 3D while filming The Twonky and Oboler became interested.[6]

Production edit

Oboler announced the project in March 1952. He said it would be called The Lions of Gulu and would include footage shot in Africa several years beforehand. Filming was to start in May. It was always going to be in Natural Vision.[7]

Howard Duff and Hope Miller were the first stars signed.[8]

Eventually Duff and Miller dropped out and were replaced by Robert Stack and Barbara Britton. The title of Oboler's film was changed to Bwana Devil in June 1952.[9] (Oboler already announced he would make a second film in the format, Spear in the Sand with Lisa Howard.[10])

The film was shot in the San Fernando Valley.[11]

The Paramount Ranch, now located in The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, sat in for an African savanna. There is now a hiking trail in the area named "The Bwana Trail" to denote the locations used in Bwana Devil. Authentic African footage shot by Arch Oboler in 1948 (in 2D) was incorporated into the film. Ansco Color film was used, instead of the more expensive and cumbersome Technicolor process.

Lloyd Nolan appeared in a prologue for the film.[12]

The film was given Code approval in two dimension but not in three dimension due to a kissing scene.[13] Eventually approval was given.[14]

Release edit

The film premiered under the banner of "Arch Oboler Productions" on Wednesday, November 26, 1952, with a twin engagement at the Hollywood Paramount Theatre and the Paramount Theatre in downtown Los Angeles.[15][1] It opened to the public the following day.[16]

At all U.S. screenings of feature-length 3D films in the 1950s, the polarized light method was used and the audience wore 3D glasses with gray Polaroid filters. The anaglyph color filter method was only used for a few short films during these years. The two-strip Natural Vision projection system required making substantial alterations to a theater's projectors and providing its screen with a special non-depolarizing surface.

The film was a critical failure, but a runaway success with audiences. It opened in San Francisco on December 13, Philadelphia, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio on December 25, and New York on February 18, 1953.[17][18]

M.L. Gunzburg presents 3D, a short film produced by Bob Clampett and featuring Beany and Cecil, was screened preceding the film. Long thought lost, the short rejoined Bwana Devil for screenings at the Egyptian Theater in 2003 and 2006.

Natural Vision announced they would make 12 follow up films.[19]

United Artists edit

United Artists bought the rights to Bwana Devil from Arch Oboler Productions for $500,000 and a share of the profits and began a wide release of the film in March as a United Artists film.[20] A lawsuit followed, in which producer Edward L. Alperson Jr. claimed that he was part owner of the film after purchasing a share of it for $1,000,000 USD. The courts decided in Oboler's favor, as Alperson's claim was unsubstantiated and "under the table".

The other major studios reacted by releasing their own 3D films. Warner Brothers optioned the Natural Vision process for House of Wax. It premiered on April 10, 1953, and was advertised as "the first 3D release by a major studio". In truth, Columbia had trumped them by two days with their release of Man in the Dark on April 8, 1953.

Commercial reception edit

The film grossed $20,000 in its opening day from two theaters and went on to earn $75,000 in its first four days setting house records.[16] It earned $2.7 million in theatrical rentals in the United States and Canada in 1953.[21] United Artists ultimately ended up recording a loss of $200,000 on the film.[20]

Public reception edit

In 1989, Pink spoke fondly of the opening week of Bwana Devil at the Hollywood Paramount Theater. "They were lined up around the block". "People would come out of the movie and yell, 'Don't go in, it stinks!' But nobody listened and they went in anyway."[22]

Reviews edit

- Bosley Crowther of The New York Times said it was "a clumsy try at an African adventure film, photographed in very poor color in what appear to be the California hills".[23]

- Variety summed up the process: "This novelty feature boasts of being the first full-length film in Natural Vision 3D. Although adding backsides to usually flat actors and depth to landscapes, the 3D technique still needs further technical advances."[24]

- Hollis Alpert of The Saturday Review wrote on March 14, 1953, "It is the worst movie in my rather faltering memory, and my hangover from it was so painful that I immediately went to see a two-dimensional movie for relief. Part of the hangover was undoubtedly induced by the photography process itself. To get all the wondrous effects of the stereoscopic motion picture one has to wear a pair of polaroid glasses, made—so far as I could determine—from tinted cellophane and cardboard. These keep slipping off, hanging from one ear, or sliding down the nose, all the while setting up extraneous tickling sensations. And once you have them adjusted and begin looking at the movie, you find that the tinted cellophane (or whatever it is) darkens the color of the screen, so that everything seems to be happening in late afternoon on a cloudy day. The people seem to have two faces, one receding behind the other; the screen becomes unaccountably small, as though one is peering in at a scene through a window. Everything keeps getting out of proportion. Nigel Bruce will either loom up before you or look like a puppet. Sometimes there is depth and sometimes there isn't. One thing is certain: it was all horribly unreal."[25]

In popular culture edit

Life magazine photographer J. R. Eyerman took a series of photos of the audience wearing 3D glasses at the premiere. One of the photos was published as a full page in the magazine and has become iconic. It was also used as the cover of Life, The Second Decade, 1946–1955, a book published in conjunction with an exhibition of photographs from Life held at the International Center of Photography, New York.[26] Another of the photos was used as a symbol of alienation under capitalism, for the American cover of Guy Debord's book The Society of the Spectacle (1973). The photo used for Debord's book shows the audience in "a virtually trance-like state of absorption, their faces grim, their lips pursed". However, in the one chosen by Life, "the spectators are laughing, their expressions of hilarity conveying the pleasure of an uproarious, active spectatorship."[27] The Debord version is also flipped left to right and cropped.[28]

Availability edit

- Bwana Devil played at the Second World 3D Film Expo on September 13, 2006, in two strip polarized 3D at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood, Ca.

- The film was never released on VHS and has not been released on DVD or Blu-Ray, but is available on Amazon Video (as of October 2020).[29]

References edit

- ^ a b Bwana Devil at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ a b Thompson, Howard (November 4, 1961). "NEW OBOLER FILM TO OPEN TUESDAY; '1 Plus 1' Is the Writer's First Movie in Nine Years". The New York Times. p. 14.

- ^ "Variety Film Reviews". Variety. December 3, 1952. p. 6.

- ^ "Harrison's Reports and Film Reviews". Harrison's Reports. December 6, 1952. p. 195.

- ^ a b Sala, Ángel (October 2005). "Apéndices". Tiburón ¡Vas a necesitar un barco más grande! El filme que cambió Hollywood (1st ed.). Festival Internacional de Cinema de Catalunya. p. 114. ISBN 84-96129-72-1.

- ^ Richard Dyer MacCann (Aug 5, 1952). "Polaroid Spectacles Required For Feature Picture in Color: Hollywood Letter". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 5.

- ^ A. H. WELLER (Mar 23, 1952). "NOTED ON THE LOCAL SCREEN SCENE". The New York Times. p. X5.

- ^ HEDDA HOPPER (Apr 16, 1952). "Phyllis Thaxter Will Play Wife of Cooper". Los Angeles Times. p. B8.

- ^ "MOVIELAND BRIEFS". Los Angeles Times. 24 June 1952. p. A7.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (July 4, 1952). "Drama: Coogan Changing Type in Mad Scientist Role; Debbie Star Part Looms". Los Angeles Times. p. A7.

- ^ THOMAS M. PRYOR (6 July 1952). "HOLLYWOOD SURVEY: Arch Oboler's Africa and Natural Vision -- 'Ivanhoe' Source -- Politics". The New York Times. p. X3.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (Sep 9, 1952). "Eleanor Parker to Be Star for Her Husband". Los Angeles Times. p. A6.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (Nov 25, 1952). "Natural Vision Plan Aimed at Hayworth; Film Refused Code Approval". Los Angeles Times. p. 21.

- ^ THOMAS M. PRYOR (Dec 13, 1952). "HUGHES IS NAMED TO BOARD AT R. K. O.: Former Major Stockholder and Two Other Ex-Officials to Serve as Directors". The New York Times. p. 19.

- ^ "'Bwana Devil' to Premiere". Los Angeles Times. 6 November 1952. p. A9.

- ^ a b "'Bwana' Boffo". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "'BWANA DEVIL' SETS RECORD". Los Angeles Times. Dec 4, 1952. p. B10.

- ^ THOMAS M. PRYOR (Dec 7, 1952). "HOLLYWOOD SURVEY: R.K.O. Victory in Screen Credits Case Poser for Creative Artists -- Addenda". The New York Times. p. X9.

- ^ THOMAS M. PRYOR (Nov 25, 1952). "12 FILMS TO BE SHOT IN NATURAL VISION: Feature-Length Pictures Slated for Stereoscopic Process -- 'Bwana Devil' Debut Set". The New York Times. p. 35.

- ^ a b Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780299114404.

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1953". Variety. January 13, 1954. p. 10.

- ^ Johnson, Lawrence A. (October 17, 2002). "S. Pink, Made Low-Budget Films". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. p. 24.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (November 12, 2015). "Immersive Technology Debuts, in the Movie Ads". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Review: Bwana Devil". Variety. Penske Business Media, LLC. December 31, 1951. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Alpert, Hollis (March 14, 1953). "The Movies: The Big Switch". Saturday Review. p. 37.

- ^ Getty Images # 2905087 Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine J. R. Eyerman's iconic photo of a bespectacled 3D audience at the Hollywood premiere of Bwana Devil.

- ^ Thomas Y. Levin Dismantling the Spectacle: The cinema of Guy Debord

- ^ Eyerman original version[permanent dead link] later used by Debord

- ^ [1], https://www.amazon.com/Bwana-Devil-Robert-Stack/dp/B009B36B00/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=bwana+devil&qid=1602203844&s=instant-video&sr=1-1.

External links edit

- Bwana Devil at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Bwana Devil at IMDb

- Bwana Devil at AllMovie