Summary

The Cascade Tunnel refers to two railroad tunnels, its original tunnel and its replacement, in the northwest United States, east of the Seattle metropolitan area in the Cascade Range of Washington, at Stevens Pass. It is approximately 65 miles (105 km) east of Everett, with both portals adjacent to U.S. Route 2. Both single-track tunnels were constructed by the Great Northern Railway.

The eastern portal of Cascade Tunnel in 2012 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | BNSF Scenic Subdivision (formerly Burlington Northern and Great Northern) |

| Location | Stevens Pass, Washington, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 47°44′33″N 121°04′10″W / 47.74250°N 121.06944°W |

| Status | Active |

| Crosses | Cascade Range, near Stevens Pass |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1929, 95 years ago[1][2] |

| Traffic | Railroad |

| Character | Primarily freight service Some passenger service (Amtrak) |

| Technical | |

| Length | 7.80 miles (12.55 km) |

| No. of tracks | Single |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Highest elevation | 2,881 feet (880 m) |

| Route map | |

| |

| |

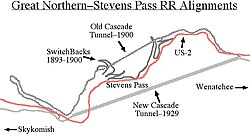

The first was 2.63 miles (4.23 km) in length and opened in 1900 to avoid problems caused by heavy winter snowfalls on the original line that had eight zig zags (switchbacks). The current tunnel is 7.8 miles (12.6 km) in length and entered service in early 1929,[1][2] approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south of and 500 feet (150 m) lower in elevation than the original. The present east portal is nearly four miles (6.5 km) east of the original and is at 2,881 feet (878 m) above sea level, 1,180 feet (360 m) below the pass. The tunnel connects Berne in Chelan County on its east with Scenic Hot Springs in King County on its west and is the longest railroad tunnel in the United States.

History edit

Original tunnel edit

Construction began on the first tunnel on August 20, 1897, and was completed on December 20, 1900. The tunnel was 2.6 miles (4.2 km) long. John Frank Stevens was the principal engineer on the interim switchback route (opened in 1893, with grades up to 4 percent) and the first Cascade Tunnel. Stevens Pass, located above the tunnels, was named after him.

The tunnel had a fume problem from the coal-burning steam locomotives. It was built with a 1.7% (1:58.8) gradient eastbound, which was too close to the ruling gradient of 2.2%. Because of the steepness of the line, the locomotives had to pull hard to make the grade and thus burn more coal, which would lead to immense smoke in the bore. The tunnel was electrified, with the project completed on July 10, 1909, eliminating the problem. The unusual system used was three-phase AC, 6600 volts at 25 Hz, from a 5 MW hydroelectric plant on the Wenatchee River just west of Leavenworth. The tunnel section only was electrified; 4.0 route miles (6.4 km) or 6.0 track miles (9.7 km) and 1.7 percent grade through the tunnel chamber.

The motive power for the section consisted of four GN boxcab locomotives supplied by the American Locomotive Company; they used electrical equipment from General Electric and were of 1,500 horsepower (1,100 kW) and weighed 115 short tons (104 t) each.[3][4] Initially three locomotives were coupled together and hauled trains at a constant speed of 15.7 mph (25.3 km/h),[5] but when larger trains required four locomotives the motors were concatenated (cascade control), so that the speed was halved to 7.8 mph (12.6 km/h) to avoid overloading the power supply. The consulting engineer, Cary T. Hutchinson, published a detailed description of the system in 1909.[6]

The tunnel was still plagued by snow slides in the area. On March 1, 1910, an avalanche at Wellington (renamed Tye after the disaster) near the west portal of the original 2.6 miles (4.2 km) Cascade Tunnel, killed 96[7]-101[8] people, the deadliest avalanche disaster in U.S. history.[9] This disaster prompted the construction of the current tunnel.

The old tunnel was abandoned in 1929, after the new longer and lower tunnel was opened. During the winter of 2007–2008, a section of the roof caved in and created a debris dam inside the tunnel, making it impassable to pedestrians due to standing water and ceiling debris. A warning was issued to stay clear of the western side of the old tunnel for a distance of 0.5 mi (0.80 km) for the indeterminate future.

Current tunnel edit

The new Cascade Tunnel was opened on January 12, 1929.[1][2] The new line had 72.9 route mi (117.3 km) or 93.2 route miles (150.0 km) electrified, between Skykomish and Wenatchee. The ruling grade was still 2.2 percent, although 21 miles (34 km) of 2 percent or worse grade was eliminated. The line length was reduced by 8.7 miles (14 km), and maximum elevation was lowered by 502 feet (153 m) from 3,382 feet (1,031 m) to 2,881 feet (878 m).

The new tunnel was started in December 1925, and was built in just over three years by A. Guthrie of St. Paul, Minnesota; the aim was to finish by the winter of 1928–1929 so that further maintenance on deteriorating snow sheds could be avoided. Project manager and engineer Frederick Mears was assigned to make sure the project was completed.[10][11]

While the new tunnel was being constructed, the Great Northern received delivery of five new electric locomotives. The new locomotives had a motor-generator supplying DC traction motors, and the single-phase AC supply required only one instead of two overhead conductors. Hence, the Great Northern re-electrified 21 miles (34 km) of the original route at single-phase (11 kV, 25 Hz) AC, including 8 miles (13 km) that were subsequently abandoned upon completion of the new tunnel, and used steam locomotives on the short remaining stretches of the old line.

On March 5, 1927, the three-phase electrification was abandoned, and the new locomotives were placed in service between Skykomish and the east portal of the old tunnel; the time was reduced from 4 hours for a 2,500 short tons (2,300 t) eastbound train to 1 hour 45 minutes for a 3,500 short tons (3,200 t) train. Furthermore, for the first time regenerated power could be used by another train or fed back to the utility company (power from regenerative braking was previously dissipated in a water rheostat at the power station).[12]

Two years later, the new tunnel opened.[12] It was the longest railroad tunnel in the Americas until 1989, when the Mount Macdonald Tunnel in British Columbia was completed, moving the Cascade into second place.

Electrification was removed in 1956, after a ventilation system was installed to eliminate diesel fumes.[13]

On April 4, 1996 an eastbound freight train broke through the doors at the east portal after they did not open properly. There were no injuries, but the broken doors slowed operations for a couple of days while replacement doors were brought up from the Seattle area.[citation needed]

Operations edit

The current Cascade Tunnel is in full operation and receives regular maintenance from BNSF Railway. The new alignment is a straight-line tunnel running between Berne and Scenic Hot Springs. It is currently part of the BNSF Scenic Subdivision between Seattle and Wenatchee, and Amtrak's Empire Builder runs through it. Because of safety and ventilation issues, this tunnel is a limiting factor on how many trains the railroad can operate over this route from Seattle to Spokane. The current limit is 28 trains per day.[14] Speed through the tunnel is 30 mph (48 km/h) for passenger trains, 25 mph (40 km/h) for freight trains.

The gradient in this tunnel is 1.565% (1:64), with the rise from west to east. The gradient is 2.2% on the west side from the town of Skykomish. Most recently, telecommunications assets and track sections inside the tunnel were improved.[when?]

Ventilation operations edit

Because of the length of the tunnel, an unusual system is used to ensure that the air inside remains breathable and reduce problems with excess fumes. As a train enters the west portal of the tunnel, a red-and-white-checkered door closes on the east portal and huge fans blow in cool air through a second portal to help the diesel engines. As long as the train is within the tunnel, the fans work with reduced power to avoid pressure problems. When the train is 0.5 miles (1 km) to the tunnel exit, the door opens in earnest.[citation needed]

Once the train has cleared the tunnel, the door closes again and the fans operate for 20 to 30 minutes with maximum power to clear the tunnel of exhaust before the next train passes through. In the opposite direction, the door opens when the train is within 0.6 miles (1 km). The fans are powered by two 800 horsepower (600 kW) electric motors, clearing the air through the seven miles (11 km) of tunnel within 20 minutes. Present-day train crews carry portable respirators for use in the event of a fan failure or a train stalling inside the tunnel. In addition, there are emergency/safety stations spaced 1,500–2,500 feet (460–760 m) apart, depending on the location within the tunnel, that provide additional air tanks and equipment to be used in the event of a ventilation/other failure.

The tunnel door is protected by an absolute signal near the east portal; on the west side, another signal with dual-flashing lunar aspects indicates to eastbound trains that the tunnel fans are operating.

See also edit

- Flathead Tunnel, an active tunnel in Montana also built by the Great Northern

- GN W-1, large electric locomotives used on the Cascade Tunnel route

- Lists of tunnels

- Moffat Tunnel, a similar railroad tunnel in Colorado

- Mount Macdonald Tunnel, a similar railroad tunnel in British Columbia

- Otira Tunnel, a tunnel in New Zealand with similar characteristics

- Snoqualmie Tunnel, Milwaukee Road near Snoqualmie Pass (inactive, now a rail trail)

- Stampede Tunnel, Northern Pacific at Stampede Pass

Notes edit

- ^ a b c "Great tunnel opening ready". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. January 12, 1929. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Wheels thunder in wonder bore". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). January 13, 1929. p. 1, part 1.

- ^ "Electric Locomotives for the Great Northern". The Railroad Gazette. 46 (1): 120–122. 1909.

- ^ Haut (1969), p. 27.

- ^ American Railway Association (1922), p. 901.

- ^ Hutchinson (1909).

- ^ Roe, JoAnn (1995). Stevens Pass. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers. pp. 79–91. ISBN 0-89886-371-6.

- ^ Middleton (1974).[page needed]

- ^ https://www.king5.com/article/news/history/deadliest-avalanche-us-history-stevens-pass-washington

- ^ Cascade Tunnel (Part 1) (1929).

- ^ Jordan, Lee. "Railroad Created Alaska's Largest City". Echo News. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ a b Middleton (1974), p.163-9.

- ^ Hidy et al. 2004, pp. 267–268

- ^ "Washington State, 2010–2030 Freight Rail Plan, pg 81" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-12-24. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

References edit

- Hutchinson, Cary T. (1909). "The electric system of the Great Northern railway company at Cascade tunnel". Proceedings of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. 28 (11): 1409–1447. doi:10.1109/PAIEE.1909.6660192. S2CID 51673934.

- American Railway Association, (Division V - Mechanical) (1922). Wright, Roy V.; Winter, Charles (eds.). Locomotive Cyclopedia of American Practice (6th ed.). New York, NY: Simmons-Boardman Publishing. OCLC 6201422.

- Cascade Tunnel (Part 1) (14 June 1929), "The Cascade Tunnel : Great Northern Railway, U.S.A (No.I)" (PDF), The Engineer, 147: 644–646

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Cascade Tunnel (Part 2) (21 June 1929), "The Cascade Tunnel : Great Northern Railway, U.S.A (No.II)" (PDF), The Engineer, 147: 672–674

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Cascade Tunnel (Part 3) (28 June 1929), "The Cascade Tunnel : Great Northern Railway, U.S.A (No.III)" (PDF), The Engineer, 147: 698–700

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Haut, F.J.G. (1969). The History of the Electric Locomotive. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. ISBN 004-385042-1.

- Hidy, Ralph W.; Hidy, Muriel E.; Scott, Roy V.; Hofsummer, Don L. (2004) [1988]. The Great Northern Railway: A History. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. ISBN 978-0-816-64429-2. OCLC 54885353.

- Legg, John F. "UCRS-Reference (GN Stevens Pass)". Archived from the original on 2005-03-14. Retrieved 2005-02-25.

- Middleton, William D. (1974). When the steam railroads electrified. Kalmbach Books. ISBN 0-89024-028-0.

- Wood, Charles; Dorothy Wood (1989-06-01). The Great Northern Railway. Pacific Fast Mail. ISBN 978-0-915713-19-6.

External links edit

- Scientific American n.s. v.137 1927. Scientific American, July 1927 - America's Longest Tunnel.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Lee Pickett Photographs Over 1400 photographs documenting scenes from Snohomish, King and Chelan Counties in Washington State from the early 1900s to the 1940s. Includes images of the Cascade Tunnel construction.

- Cascade Tunnel # 15 — Pictures and details of the "Fanhouse" at the east portal of the tunnel

- Radio Broadcast of the 1929 Cascade Tunnel Dedication

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936), "Tunnelling against time", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 47–52 illustrated description of the construction of the second Cascade tunnel