Summary

Chika Kuroda (黒田チカ; 24 March 1884 – 8 November 1968) was a Japanese chemist whose research focused on natural pigments. She was the first woman in Japan to receive a Bachelor of Science.

Chika Kuroda | |

|---|---|

黒田チカ | |

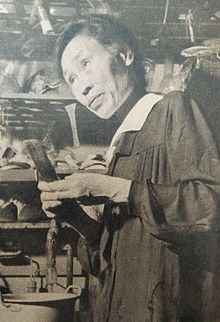

Kuroda in 1948 | |

| Born | 24 March 1884 |

| Died | 8 November 1968 (aged 84) Fukuoka, Japan |

| Awards | Majima Prize |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater |

|

| Influences |

|

| Academic work | |

| Institutions |

|

| Main interests | Organic chemistry |

| Notable ideas | Natural dye |

Biography edit

Chika Kuroda was born in Saga, Kyushu on 24 March 1884, the third daughter of her father Kuroda Heihachi (1843–1924) and her mother Toku.[1]

She attended the Women's Department of Saga Normal School, graduating in 1901, and worked as a teacher for a year afterward. She entered the Division of Science at Rika Women's Higher Normal School in 1902 and graduated in 1906. She then taught at Fukui Normal School for a year before enrolling in the graduate program at Kenkyuka Women's Higher Normal School in 1907. She finished the course in 1909 and became an assistant professor at Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School. In 1913, when Tohoku Imperial University became the first of Japan's Imperial Universities to accept women students, she was admitted to the Chemistry Department of the College of Science among the first cohort of women. She was mentored by Professor Riko Majima, who inspired Kuroda's interest in organic chemistry, particularly natural pigments; he supervised her research into the purple pigment of Lithospermum erythrorhizon.[2] She completed her Bachelor of Science in 1916, becoming the first woman in Japan to do so.[3]

Kuroda was appointed an assistant professor at Tohoku Imperial University upon graduating in 1916 and became a professor at Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School in 1918. The same year, she became the first woman to give a presentation to the Chemical Society of Japan when she presented her research on the pigment of L. erythrorhizon.[3] She travelled to the University of Oxford in 1921, where she researched phthalonic acid derivatives under William Henry Perkin. She returned to Japan in 1923 and resumed her role as professor at Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School. In 1924, she was commissioned by the RIKEN institute to research the structure of carthamin, the pigment of safflower plants. Her thesis on the subject, "The Constitution of Carthamin", earned her a doctorate in science in 1929.[2][4] She was the second woman in Japan to receive such a degree, after Kono Yasui.[5]

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Kuroda's research examined the pigments of the Asiatic dayflower, eggplant skin, black soybeans, red shiso leaves, and sea urchin spines, as well as derivatives of naphthoquinone.[2] She was awarded the Majima Prize by the Chemical Society of Japan in 1936. She was appointed professor at Ochanomizu University in 1949, and at the same time began researching the pigmentation of onion skin. Her extraction of quercetin crystals from onion skin led to the creation of Kerutin C, an antihypertensive drug.[2][3] She retired in 1952, but continued to lecture at Ochanomizu University as a professor emeritus. She was awarded a Medal with Purple Ribbon in 1959 and was conferred the Order of the Precious Crown of the Third Class in 1965. She developed heart disease in 1967 and died on 8 November 1968 in Fukuoka, aged 84.[2]

Legacy edit

Tohoku University created the Chika Kuroda prize in 1999 to recognize outstanding accomplishments for graduate students in science.[4]

A statue of Kuroda stands on the main street of Saga.[1]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b Siderer, Yona (4 November 2022). "Kuroda Chika (1884–1968) – Pioneer Woman Chemist in Twentieth Century Japan". Substantia. 7. Firenze University Press: 93–112. doi:10.36253/Substantia-1792. This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c d e "Chika Kuroda (1884~1968)". Ochanomizu University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Haines, Catharine M. C. (2001). International Women in Science: A Biographical Dictionary to 1950. ABC-CLIO. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-57607-090-1.

- ^ a b "About TUMUG >> Archive". Tohoku University Center for Gender Equality Promotion. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Kodate, Naonori; Kodate, Kashiko (2015). Japanese Women in Science and Engineering: History and Policy Change. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-317-59505-2.