Summary

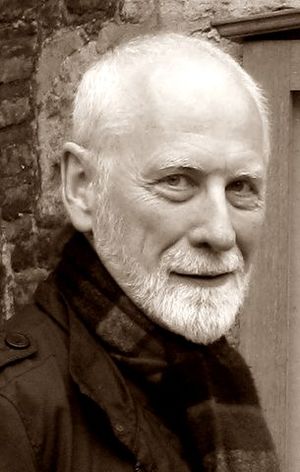

Christopher Herrick is an English concert organist best known for his interpretation of J.S. Bach’s organ music and for his many recordings on the finest pipe organs from around the world.

Christopher Herrick | |

|---|---|

Christopher Herrick | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 23 May 1942 Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Genres | Classical music |

| Occupation(s) | Concert organist, harpsichordist and conductor |

| Instrument(s) | Organ (pipe) |

| Years active | 1960–present |

| Labels | Hyperion |

| Website | www |

Early life edit

Born in Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, Herrick was a boy chorister at St Paul's Cathedral and attended its choir school; aged 11, he sang at the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II and later that year went with the choir on a three-month forty-concert tour of USA and Canada, which included a private concert in the White House and a brief conversation with President Dwight D. Eisenhower. At the age of 12, he was inspired to learn the organ after Sir John Dykes Bower, organist of St Paul's, asked him to accompany him to the cathedral organ loft to turn pages for him for a BBC recording.[1] He describes this as his “Damascus moment”.[2] Herrick later, as a Music Scholar, attended Cranleigh School, where he was able to pursue his organ studies.[3]

Student days edit

From 1961 to 1964, Herrick held the Parry/Wood Organ Scholarship at Exeter College, Oxford, where he worked towards an Honours Degree in Music (MA), as well as being effectively Director of Music of the Chapel Choir and conductor of the Exonian Singers and Orchestra.[4] Following this, he obtained a Boult scholarship to study at the Royal College of Music, where he studied conducting with Sir Adrian Boult,[5] and where his interests expanded to the harpsichord, encouraged by his professor Millicent Silver.[6] Herrick had studied organ privately with Geraint Jones, who post-war had been sent to give organ concerts in Germany by the British Council and the BBC.[7] As well as being an inspiring teacher, Geraint Jones described and passed on his experiences of playing the historic German organs with their mechanical actions, straight pedal boards and direct, clear sonority, particularly suited to the organ music of J.S.Bach.[2]

Professional career edit

Organist edit

Until 1984, Herrick had held liturgical posts in church, cathedral and abbey, first as Choirmaster and Organist of St Mary’s Primrose Hill, North London from 1964 to 1967,[8] then as Assistant Organist at St Paul's Cathedral from 1967 to 1974, and from 1974 to 1984 as an organist at Westminster Abbey.[9][10] While at Westminster Abbey, he played at royal and state occasions including Earl Mountbatten’s Ceremonial Funeral,[11] gave over 200 solo recitals on the Abbey organ, and played at both Sir William Walton’s 80th Birthday Concert and his Funeral Service less than a year later.[12]

In his last year at Westminster Abbey Herrick met Ted Perry, the owner-director of Hyperion Records, who proposed an album of “virtuosic repertoire”, on the Abbey's Harrison & Harrison organ. Released in 1984,[13] this CD entitled Organ Fireworks led to well over 40 solo organ Herrick/Hyperion CD recordings. On the strength of his new exclusive relationship with Hyperion Records and some planned BBC Radio 3 recording tours in Europe as well as healthy bookings for organ concerts, Herrick embarked in 1984 upon a solo career as an international concert organist, staging concerts over the years on a stunning range of organs in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand; United States and Canada; Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland and Finland; France, Switzerland and Germany, The Netherlands, Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain and Italy; South Africa, Hong Kong and Japan.[14] Notably, he gave the solo organ concert during the 1994 centenary season of the BBC Henry Wood Proms, when he played a programme exclusively of English music including Robin Holloway’s monumental ‘Organ Fantasy’ op. 65.[15]

Herrick is best known for his interpretation of Bach’s organ music, recording the complete organ works on seven Metzler organs throughout Switzerland compiled between 1989 and 1999,[n 1] recorded on 16 CDs for Hyperion.[17] Bach's complete organ works were subsequently performed at two marathon events, firstly in 1998 at the Lincoln Center Festival in New York, when he played fourteen concerts on consecutive days on the Kuhn organ in Alice Tully Hall,[18][n 2] and again in 2014 at the Mariinsky Concert Hall, St Petersburg, this time twelve concerts performed over a more extended period of five months.[20]

Hyperion followed up the 1984 Organ Fireworks disc from Westminster Abbey with 13 more discs, culminating in Organ Fireworks 14 recorded in 2010 at the Town Hall, Melbourne,[21] on the 1929 Hill, Norman & Beard organ - much enlarged and rebuilt by the American organ builder Schanz in 2001. As contrast to the more flamboyant Organ Fireworks CDs Hyperion also issued four discs entitled Organ Dreams.[22]

From the mid-nineties, Herrick made acclaimed recordings on European organs featuring other composers including Louis-Claude Daquin,[23][n 3] Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck,[24][n 4] Josef Rheinberger,[25] and in 2007, commenced work on a five-year project to record the complete organ works of Dieterich Buxtehude.[26]

Two more recent recordings for Hyperion have been Power of Life[27] recorded in 2015 on the Metzler organ in Poblet Monastery in Catalonia, and Northern Lights,[28] recorded in 2020 on the Steinmeyer organ in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, Norway.

Other professional interests edit

In 1973, Herrick secured the loan of a rare Dulcken harpsichord, which led to the formation of the Taskin Trio (violin, viola da gamba, harpsichord), performing baroque music on period instruments,[29] and gave solo recitals of Bach's complete Well-Tempered Clavier on the Dulcken harpsichord at London's Purcell Room.[30]

Herrick, who had previously conducted the Exonian Singers and Orchestra at Oxford, once again took up the baton in 1974, being appointed Conductor of Twickenham Choral, a position he still holds today.[5] He was also conductor of Whitehall Choir from 1978 to 2000.[31] Both choirs were substantial groups of up to 100 fully auditioned members, whom he occasionally combined in performances at Westminster Abbey, Guildford Cathedral and the Royal Albert Hall.[32]

Herrick lives in Kingston upon Thames where for many years he was able to play the Frobenius organ of Kingston Parish Church.[33] He now rehearses on the Harrison & Harrison organ at St Mary’s Church, Twickenham and the Tickell organ at Betchworth Church.[34]

Selected discography edit

By 2022, Herrick had recorded 45 albums with Hyperion, most notably:

- Organ Fireworks, 14 volumes (Hyperion Records, 1984-2010)

- Johann Sebastian Bach: The Complete Organ Works (Hyperion Records, [1] CDS44121/36, 2002)

- Power of Life - Metzler organ of Poblet Monastery, Tarragona, Spain (Hyperion Records, [2] CDA68129, 2015)

Sources edit

- Stanley Webb: Herrick, Christopher, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 6 May 2007), <http://www.grovemusic.com Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine>

- Malcolm Bruno: Interview with Christopher Herrick, Choir & Organ (May/June 2002)

- The Wall Street Journal, Personal Journal, Time Off/Backstage: Christopher Herrick (29 October 2004)

Notes edit

- ^ Patsy Morita, reviewing Herrick's 1990 recording of Bach's Toccatas and Fugues (part of his complete organ works of Bach for Hyperion), writes that he chooses a “more conservative approach" to make the music more like what it would have been on a Bach-era organ. The "famous Toccata and Fugue", BWV 565, is "therefore, not the blusterous piece that many recognize. It's a more thoughtful and considered reading." Morita finds the variety of music of BWV 582 "fascinating"; in her view, Herrick shows what matters in the pieces "while making them eminently agreeable".[16]

- ^ a critic from The New York Times wrote: "Mr Herrick was at the peak of his considerable form, combining precision with panache, interpretive freedom with sheer joy in virtuosity. The playing was, in a word, triumphant".[19]

- ^ on the restored 1739 Parisot organ in St Rémy, Dieppe

- ^ on a copy of the 17th-century organ of Stockholm's German church, now in Norrfjärden in northern Sweden. Herrick utilised historically informed performance practice, including original fingerings, not using the thumb very much, which caused some difficulties: "only when I went in for physical therapy did I finally adapt."

References edit

- ^ Anon. "Biography: Christopher Herrick". All Music. ALLMUSIC, NETAKTION LLC. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b Bruno, Malcolm (2002). "The Right Man". Choir & Organ. 10 (3).

- ^ Rogers, Curtis (2011). "Cranleigh School Organ". Organ. 89 (355): 28–31.

- ^ Anon. "Concert Programmes - Oxford Concert Programmes: Box 7 (1963-65)". Concert Programmes. Arts and Humanities Research Council. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ a b Mumford, Adrian; Herrick, Sarah (2022). Twickenham Choral Centenary. Twickenham Library: Twickenham Library. p. 43.

- ^ Anon. "Millicent Silver". Hyperleap. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Blyth, Alan (8 May 1998). "Obituary: Bidding for baroque: Geraint Jones". No. A76100366. The Guardian (London England). The Guardian Newspaper. p. 26.

- ^ Anon (2001). "Organists and Choirmasters at St Mary's, Primrose Hill, London". Choir & Organ. 9 (6).

- ^ Bowyer, Kevin (2021). "Well Thumbed No.3". Organist's Review. 5. f Incorporated Association of Organists Trading Limited (IAO Trading Limited).

- ^ Anon (1 October 1998). "St. Joseph Musical Society to Sponsor Recital By Internationally-Known Organist Christopher Herrick in Detroit November 1". Gale Academic OneFile. PR Newswire Association LLC. p. 1952.

- ^ Anon. "Organ Fireworks Vol. 1". Hyperion. Hyperion Records. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Barone, Michael (20 October 2010). "Christopher Herrick in Wayzata". Your Classical Radio. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Anon. "Organ Fireworks". Sonemic, Inc. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Delcamp (2018). "Organ fireworks--world tour". Vol. 80, no. 4. Record Guide Productions. American Record Guide. p. 188.

- ^ Anon (13 August 1994). "BBC Radio 3". No. 65032. Times Newspapers Ltd. The Times. p. 92.

- ^ Morita, Patsy. "Review: Bach Toccatas and Fugues". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ David Alkar. "16 CD Set - JS Bach: The Complete Organ Music". Musical Opinion Ltd. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Oestreich, James R. (15 July 1998). "The Glories Of Bach, From Grand To Playful (James R Oestreich reviews organ recital by English organist Christopher Herrick, first of daily series of 14 hour-long recitals at Alice Tully Hall; series is billed as 'complete' organ works of Bach, and is part of Lincoln Center Festival '98)". The New York Times. No. Arts. The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Oestreich, James R. (28 July 1998). "Festival review / Bach as Mountain Range (James Oestreich reviews Christopher Herrick's performance of works by Bach, as part of Lincoln Center Festiva )". The New York Times. No. Arts. The New York Times. p. 5.

- ^ Buchanan, Clare (19 February 2014). "Prince of Wales pulls some strings as classical stars gather at Hampton Court Palace". Times Newspapers Ltd. The Times.

- ^ Duperron, Jean-Yves. "ORGAN FIREWORKS - Volume 14 - Christopher Herrick (Organ) - Organ of Melbourne Town Hall". Classic Music Sentinel. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Chris Bragg. "Organ Dreams Volume 4". Musicweb International. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Brian Wilson. "Puer nobis nascitur: Christmas Carols". Musicweb International. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Jonathan Freeman-Attwood. "Sweelinck Organ Works - Cleanly executed but often unexplored performances of the great Dutch master". Gramophone - MA Business and Leisure Ltd. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Jerry Dubbins. "Christopher Herrick, Paul Barritt, Richard Lester - Rheinberger: Suites for Organ, Violin and Cello (2005)". isRAbox. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ John Quinn. "Dieterich BUXTEHUDE (c.1637-1707) - Complete organ Works -Volume 5". Musicweb International. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Marc Rochester. "Christopher Herrick: Power of Life". Gramophone - MA Business and Leisure Ltd. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ John Quinn. "Northern Lights". Musicweb International. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Harrison, Max (21 February 1976). "London débuts". No. 60228. Times Newspapers Ltd. The Times. p. 9.

- ^ Anon (17 April 1976). "Royal Festival Hall". No. 59681. Times Newspapers Ltd. The Times. p. 9.

- ^ Anon. "Whitehall Choir". Whitehall Choir. Whitehall Choir a registered charity (no. 280478). Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Anon. "Whitehall Choir nears 60 – a brief history" (PDF). Whitehall Choir. Whitehall Choir a registered charity (no. 280478). Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ All Saints Kingston - The Frobenius Organ Archived 8 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Anon (5 August 2015). "Music at St Michael's". St Michael's Church Betchworth. St Michael's Church Council. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

External links edit

- Official website

- Hyperion records: Christopher Herrick [3]