Summary

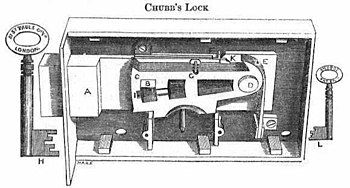

A Chubb detector lock is a lever tumbler lock with an integral security feature, a re-locking device, which frustrates unauthorised access attempts and indicates to the lock's owner that it has been interfered with. When someone tries to pick the lock or to open it using the wrong key, the lock is designed to jam in a locked state until (depending on the lock) either a special regulator key or the original key is inserted and turned in a different direction. This alerts the owner to the fact that the lock has been tampered with.

Any person who attempts to pick a detector lock must avoid triggering the automatic jamming mechanism. If the automatic jamming mechanism is accidentally triggered (which happens when any one of the levers is lifted too high) the lock-picker has the additional problem of resetting the detector mechanism before the next attempt to open the lock. This introduces additional complexity into the task, increasing the degree of lock-picking skill required to a level which few people have. The first detector lock was produced in 1818 by Jeremiah Chubb of Portsmouth, England, as the result of a government competition to create an unpickable lock. It remained unpicked until the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Development edit

In 1817, a burglary in Portsmouth Dockyard was carried out using false keys, prompting Her Majesty's Government to announce a competition to produce a lock that could be opened only with its own unique key.[1] In response, Jeremiah Chubb, who was working with his brother, Charles, as a ship's outfitter and ironmonger in Portsmouth,[2][3] invented and patented his detector lock in 1818.[4] Building on earlier work by Robert Barron and Joseph Bramah, Jeremiah developed a four-lever lock that, when subjected to attempted picking, or use of the wrong key, would stop working until a special key was used to reset it. This security feature was known as a regulator, and was tripped when an individual lever was pushed past the position required to bring the lever in line to open the lock. This innovation was sufficient for Jeremiah to claim the £100 reward on offer (equivalent to £7,800 in 2021).

A locksmith who was a convict aboard one of the prison hulks in Portsmouth Docks was given the Chubb lock with a promise of a free pardon from the Government and £100 from Jeremiah if he could pick the lock. The convict, who had successfully picked every lock with which he had been presented, was confident he could do the same with the detector lock. After two or three months of trying he admitted defeat.[5][6]

Manufacture and improvements edit

In 1820, Jeremiah joined his brother Charles in starting their own lock company, Chubb Locks. They moved from Portsmouth to Willenhall in Staffordshire, the lockmaking capital of Great Britain, and opened a factory in Temple Street. In 1836 they moved to St James' Square in the same town. A further move to the site of the old workhouse in Railway Street followed in 1838. The Chubb lock reportedly became popular as a result of the interest generated when King George IV accidentally sat on a Chubb lock that still had the key inserted.[7][verification needed][8][failed verification]

A number of improvements were made to the original design but the basic principle behind its construction remained unchanged. In 1824, Charles patented an improved design that no longer required a special regulator key to reset the lock. The original lock used four levers, but by 1847 work by Jeremiah, Charles, his son John and others resulted in a six-lever version. A later innovation was the "curtain", a disc that allowed the key to pass but narrowed the field of view, hiding the levers from anybody attempting to pick the lock. In due course Chubb began to manufacture brass padlocks incorporating the "detector" mechanism.

Picking edit

Competition in the lock business was fierce and there were various challenges issued in an attempt to prove the superiority of one type of lock over another. Joseph Bramah exhibited one of his locks in the window of his shop and offered 200 guineas (£210 and equivalent to £20,800 in 2021) to anybody who could devise a method of picking it. In 1832, a Mr Hart, replying to a challenge by Chubb, failed to pick one of his detector locks. After a number of people tried and failed, the first person to pick the six-lever Chubb lock was the American locksmith Alfred Charles Hobbs, the inventor of the protector lock, during the Great Exhibition in 1851.

In popular culture edit

Chubb locks are mentioned twice in the Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. In the short story "A Scandal in Bohemia", Holmes describes a house with a "Chubb lock to the door."[9] In another short story, "The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez", Holmes asks "Is it a simple key?" to which Mrs Marker, an elderly maid, replies, "No, sir, it is a Chubb's key."[10] In both of these stories, the description makes clear that the lock could not have been picked, a minor clue in solving each mystery. In R. Austin Freeman's The Penrose Mystery, Dr. Thorndyke says: “Burglars don’t try to pick Chubb locks.”[11]

A Chubb lock is featured in the novel Neuromancer by William Gibson.

Sarah MacLean's Wicked and the Wallflower, set in 1837, has a Chubb lock on the door of the Bareknuckles Bastard's smuggling warehouse. Lady Felicity Faircloth cannot pick it on her first attempt.

References edit

- ^ Ullyett, Kenneth (July 27, 1963). "Crime out of hand". M. Joseph – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Architect and Building News". July 27, 1922 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Keeping Track". Canadian National Railways. July 27, 1960 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tobias, Marc Weber (January 1, 2000). LOCKS, SAFES, AND SECURITY: An International Police Reference Two Volumes (2nd Ed.). Charles C Thomas Publisher. ISBN 9780398083304 – via Google Books.

- ^ York.), A. C. HOBBS (of New (July 27, 1868). "Locks and Safes. The construction of locks; compiled from the papers of A. C. Hobbs, ... and edited by C. Tomlinson. ... To which is added a description of ... J. B. Fenby's patent locks, and a note upon iron safes. By R. Mallet" – via Google Books.

- ^ Phillips, Bill (December 15, 2008). Locksmith and Security Professionals' Exam Study Guide. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071549820 – via Google Books.

- ^ Grunfeld, Nina (October 27, 1984). The Royal Shopping Guide. W. Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-04080-2 – via Internet Archive.

george IV sat on chubb lock.

- ^ "History of Chubb" Archived 2013-09-05 at the Wayback Machine, August 17, 2007

- ^ "A Scandal in Bohemia", The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, 1892

- ^ "The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez", The Return of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, 1905

- ^ Freeman, R. Austin. Complete Works of R. Austin Freeman (Delphi Classics) (Series Six Book 14) . Delphi Classics. Kindle Edition.

- Roper, C.A.; Phillips, Bill (2001). The Complete Book of Locks and Locksmithing. McGraw-Hill Publishing. ISBN 0-07-137494-9.

- "Lock Making: Chubb & Son's Lock & Safe Co Ltd". Wolverhampton City Council. 2005. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- "Chubb History". Chubb. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- "History of Locks". Encyclopaedia of Locks and Builders Hardware. Chubb Locks. 1958. Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- Jock Dempsey (2002). "Lockpicking for Lockmakers". Old Locks. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2006.