Summary

Clifton is an incorporated town located in southwestern Fairfax County, Virginia, United States, with a population of 243 at the time of the 2020 census.[4]

Clifton, Virginia | |

|---|---|

Main Street, historic Clifton, Virginia | |

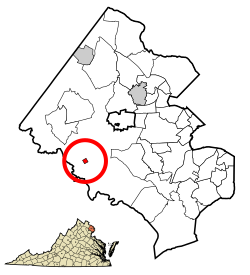

Location of Clifton in Fairfax County and Virginia | |

Clifton, Virginia Clifton  Clifton, Virginia Clifton, Virginia (Virginia)  Clifton, Virginia Clifton, Virginia (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 38°46′48″N 77°23′11″W / 38.78000°N 77.38639°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Fairfax |

| Named for | Clifton Station |

| Government | |

| • Type | Town |

| • Mayor | William R. Hollaway |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.25 sq mi (0.65 km2) |

| • Land | 0.24 sq mi (0.63 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 197 ft (60 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 234 |

| • Density | 972.0/sq mi (373.8/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 20124 |

| Area code(s) | 703, 571 |

| FIPS code | 51-17376[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1495399[3] |

| Website | clifton-va |

Incorporated by the General Assembly on March 9, 1902, Clifton is one of only three towns in the county, the other two being the much more populous Vienna and Herndon. Clifton's history begins pre-colonially, when the area was used as hunting grounds by the local Dogue Native American tribe. A railroad siding was constructed here during the Civil War, and the area became titled as Devereux Station. A nearby neighborhood on the outskirts of the Clifton ZIP code has this name. Development of a village at the siding began in 1868 when a railroad depot, named "Clifton Station", was constructed.

Unlike most areas in Northern Virginia, the land around Clifton is far less built up than nearby areas, especially to its east and southwest. This was out of the worry that overdevelopment near Bull Run and the Occoquan River would be environmentally damaging to the Occoquan Reservoir. Consequently, as development edged near the area in the late 1970s and early 1980s, an ordinance was enacted stating that only one building could be placed on 5-acre (2.0 ha) parcels that have not already been divided. Today, the southern and eastern portions of the area are heavily forested, with single-family homes, while the northern area has become equestrian areas.

History edit

Colonial era edit

Before the arrival of European settlers, the present-day Clifton area was part of the hunting grounds used by Algonquin-speaking members of the Dogue tribe. The Dogue lived in villages and towns along the Potomac River and nearby Occoquan River. They carved bowls out of soapstone found in the area.[5]

European settlers composed of Scots merchants created the first nearby port settlement in the mid-1710s near the present-day Dumfries-Triangle area.[6] Land in the Clifton area began to be settled in the early 18th century.[7]

Civil War edit

During the Civil War, the United States Military Railroad Construction Corps built a railroad siding here on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad in order to supply the Union Army with timber for railroad ties, bridge trusses, and firewood. The siding was named after John Henry Devereux, superintendent of military railroads that terminated in Alexandria. Wood from hundreds of acres was cut and hauled by wood choppers and teamsters, most of whom were escaped slaves, and transported by train to Alexandria. The laborers risked capture by working outside protected Union lines.[8][9]

In spring 1863, a wye was constructed at Devereux Siding to enable trains to turn around after the Union Army abandoned the Orange and Alexandria Railroad south of Bull Run. By June 1863 the entire railroad outside of the defenses of Washington was abandoned until the return of Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac following their successful Gettysburg Campaign. New York infantry regiments were stationed at the siding in order to protect wood station operations and the railroad from Confederate attack.[8][10]

Devereux Siding was located between the station at Union Mills and Sangster's Station. Today, there are two neighborhoods outside of the town named after the Devereux and Sangster's stations. The Orange & Alexandria Railroad extended from Alexandria to Orange, Virginia. For a brief period near the close of the war, the siding became the sixth scheduled stop for passengers and freight and became known as "Devereux Station".[11]

The O & A was the only railroad link between Alexandria and Richmond, Virginia.[10]

Village of Clifton edit

William E. Beckwith, a Black man, bequeathed his land south of the railroad to his former slaves, some of whom were his children. Harriet Harris and the five children she had with William Harris were devised the land where the village of Clifton was initially developed. Harrison G. Otis, a New York realtor, purchased a large tract of land north of the railroad from the Beckwith estate and a small lot of land south of the railroad from William Harris, where he constructed a saw mill and train depot. The depot opened in November 1868 and was named "Clifton Station". The next year, an official U.S. post office opened at the depot, and Otis built the historic Clifton Hotel.[12][13] Harrison Otis and his brother J. Sanford Otis founded the Clifton Presbyterian Church, still in existence.[10] The station no longer exists, but the town of Clifton is still standing along what used to be the O & A Railroad, now a part of the Norfolk Southern Railway.

William Harris divided a portion of his family's land adjacent to the railroad into ten lots that were offered for sale in 1869. Homes and businesses were constructed on the lots, including a general merchandise store located on the western side of Main Street adjacent to the railroad. Harris expanded the village by selling additional lots along Main Street in the mid-1870s. Harrison Otis and his business partner Margaret Hetzel subdivided land on the eastern side of Main Street for development and several lots were sold in the 1870s; however, this development was not as successful as planned due to Harrison Otis's reduced mental health and Margaret Hetzel's financial difficulties.[12]

The village grew in the late 1800s when a number of homes and businesses were constructed, including additional merchandise stores and lumber yards.

20th century edit

The town was incorporated by the General Assembly on March 9, 1902. It is currently one of the three towns in Fairfax County.

During the 1900s, the town was nearly the same size as it is now. The first schoolhouse in Clifton was in Susan Reviere Hetzel's home on Pendleton Avenue. She was also one of the founders of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The school was later moved to the side-yard area of what would later become the home of Mayors Swem Elgin and Jim Chesley. In 1912 a new schoolhouse (built for K-12) was built overlooking the town; it stood until 1952. A new elementary school, Clifton Elementary, was built on the same site in 1953 and served the community until 2010. On March 9, 1930, the Clifton General Store caught fire, and a few months later a new general store was built in its place.

By the late 1960s, the town was in a state of decline. Many houses in the town were boarded up and abandoned. A number of new families and residents began much-needed gentrification of the town. Wayne Nickum, a former mayor, worked to ensure the entire town was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Some 63 Clifton buildings were added to the register at that time. Another resident, Jim Chesley, who would also serve as mayor of Clifton, worked tirelessly with national and state politicians and administrators to ensure the town maintained its historic integrity. In 1967, the town sponsored the first Clifton Day Festival as a way to attract the public to this historic town. This celebration continues each year as a town fair and music festival on the Sunday before Columbus Day in October.

One historical home in the town is attributed to a member of the Kincheloe family, located where Main Street, County Rd 645, becomes Kincheloe Road. Kincheloe Road continues to Old Yates Ford Road.[14] Daniel Kincheloe (1723-1785), whose grandfather immigrated from Ireland, was a landowner near the town and along Popes Head Creek. He was a captain in the militia in the French and Indian Wars and provided beef and other supplies to the revolutionary army during the Revolutionary War. He is buried in the Wickliffe/Kincheloe cemetery that is now part of the Hemlock Overlook Regional Park, adjacent to a park office. Among two wives, he had 11 children, including 7 sons.[15] One of Daniel's descendants built the house in Clifton.

Towards the late 1970s and early 1980s suburban development was starting to edge near Clifton. Communities such as Burke Center, with 5,500 homes, and Little Rocky Run, with 2,722 homes, were constructed, raising concerns that the new construction might ruin the beauty of the Clifton area. In the 1980s, Fairfax County government enacted an ordinance stipulating that only one building could be placed on 5-acre (20,000 m2) parcels that have not already been divided. Single-family homes were constructed in the southern and eastern parts of Clifton, while land to the north became equestrian areas.

The town was declared a National Historic District by the US Department of the Interior in 1984.[16] The opening scenes of Broadcast News were filmed in Clifton in 1986.

Modern Clifton edit

Formation of the Occoquan Watershed in the 1970s limited development due to ecological concerns and required all houses in the area to have at least 5 acres (20,000 m2) of land. This prevents nearly all development other than luxury single-family homes. In 2002, a new community was built on the edge of town called Frog Hill. Controversy arose about demolishing the abandoned Hetzel home on the corner of Chapel Road and Pendleton Avenue in 2006. The building and a replica home were finished in the winter of 2007.

In 2000, then-mayor Jim Chesley started a Labor Day antique car show in Clifton sponsored by the Northern Virginia Custom Cruisers and Clifton Lions clubs to raise money for local charities. The ninth annual Labor Day Car Show in 2008 attracted more than 400 antique cars, an estimated two thousand visitors, and raised over $30,000. That year's featured charity was Life With Cancer, a Fairfax hospital-based program that provides family support and education. In the past five years alone, the event has raised nearly $120,000 for various local charities.

The Clifton Spring Homes Tour is run by the Clifton Community Women's Club and is held on the third Thursday in May. The 100-member General Federation of Women's Club group raises money for local charities via home tours, silent auction, boutique, and local women's art show and sale.

In 2020, the city made national headlines when a "Black Lives Matter" banner was hung in the town's Main Street. The banner was met with praise by many residents but condemnation by others including the wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas who saw it as justifying controversial aspects of the BLM movement.[17] Her comments lead to media attention on the banner. The banner was stolen on July 20, 2020, and has not been found, despite a police investigation.[18]

Geography edit

Clifton is located in western Fairfax County at 38°46′48″N 77°23′11″W / 38.78000°N 77.38639°W (38.780047, −77.386408).[19] 6 miles (10 km) southeast of Centreville and 7 miles (11 km) southwest of the city of Fairfax.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 0.25 square miles (0.65 km2), of which 0.25 square miles (0.64 km2) is land and 0.004 square miles (0.01 km2), or 1.57%, is water.[20] The Charter of the town of Clifton affirms this statement.[21] Popes Head Creek, a tributary of Bull Run, runs westward through the town.

Demographics edit

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 94 | — | |

| 1910 | 204 | — | |

| 1920 | 200 | −2.0% | |

| 1930 | 181 | −9.5% | |

| 1940 | 194 | 7.2% | |

| 1950 | 262 | 35.1% | |

| 1960 | 230 | −12.2% | |

| 1970 | 178 | −22.6% | |

| 1980 | 170 | −4.5% | |

| 1990 | 176 | 3.5% | |

| 2000 | 185 | 5.1% | |

| 2010 | 282 | 52.4% | |

| 2020 | 243 | −13.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

2020 Census edit

At the 2020 census (some information from the 2022 American Community Survey) there were 243 people, 93 housing units and 102 households residing in the town. The population density was 972.0 inhabitants per square mile (373.8/km2). The average housing unit density was 372.0 per square mile (143.1/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 95.47% White, 0.00% African American, 0.00% Native American, 0.82% Asian, 0.00% Pacific Islander, 0.82% from other races, and 2.88% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 2.88% of the population.[4]

All households were family households, of which, 85.3% were married couples, 5.9% were a male family householder with no spouse, and 8.8% were a female family householder with no spouse. The average family household had 3.87 people.[4]

The median age was 36.3, 32.4% of people were under the age of 18, and 15.9% were 65 years of age or older. The largest ancestry is the 46.9% who had English ancestry, 1.1% spoke a language other than English at home, and 2.5% were born outside the United States, 100.0% of whom were naturalized citizens.[4]

The median income for a household in the town was $219,500. 5.8% of the population were military veterans, and 82.2% had a bachelor's degree or higher. In the CDP 0.0% of the population was below the poverty line, with 0.3% of the population without health insurance.[4]

2000 Census edit

As of the 2000 census,[2] there were 185 people, 67 households, and 52 families residing in the town. The population density was 723.7 inhabitants per square mile (279.4/km2). There were 70 housing units at an average density of 273.8 per square mile (105.7/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 98.92% white, 0.54% Asian, 0.54% from other races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.54% of the population.

There were 67 households, out of which 40.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 68.7% were married couples living together, 6.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 20.9% were non-families. 13.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 3.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.76 and the average family size was 3.06.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 23.2% under the age of 18, 7.6% from 18 to 24, 32.4% from 25 to 44, 32.4% from 45 to 64, and 4.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 134.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 125.4 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $111,048, and the median income for a family was $117,446. Males had a median income of $62,188 versus $47,500 for females. The per capita income for the town was $47,459. None of the population or families were below the poverty line.

Climate edit

Clifton has a Humid Subtropical climate with cool winters, mild falls and springs, and hot summers. July is usually the warmest, and wettest month. January is usually the coldest month. On average, February is the driest month. The warmest temperature set in Clifton was 104 °F (40 °C) on July 2, 1980. The coldest temperature was −8 °F (−22 °C) set on January 8, 1982.

| Climate data for Clifton, VA | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

76 (24) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

93 (34) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

104 (40) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43 (6) |

46 (8) |

58 (14) |

68 (20) |

77 (25) |

85 (29) |

88 (31) |

87 (31) |

81 (27) |

70 (21) |

59 (15) |

47 (8) |

67 (19) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33 (1) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

73 (23) |

77 (25) |

75 (24) |

69 (21) |

57 (14) |

48 (9) |

34 (1) |

56 (13) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22 (−6) |

25 (−4) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

51 (11) |

60 (16) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

56 (13) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

21 (−6) |

45 (7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −8 (−22) |

−4 (−20) |

−5 (−21) |

19 (−7) |

29 (−2) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

40 (4) |

33 (1) |

19 (−7) |

9 (−13) |

0 (−18) |

−8 (−22) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.59 (66) |

2.46 (62) |

2.77 (70) |

2.92 (74) |

3.71 (94) |

3.23 (82) |

3.11 (79) |

3.16 (80) |

3.33 (85) |

3.08 (78) |

3.12 (79) |

2.72 (69) |

36.20 (919) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.5 (19) |

6.4 (16) |

3.4 (8.6) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.2 (3.0) |

3.4 (8.6) |

22.3 (57) |

| Source 1: [24] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [25] | |||||||||||||

Education edit

Fairfax County Public Schools serves Clifton. K-6 students in Clifton attend Union Mill Elementary School,[26] while middle and high school residents are zoned to either Liberty Middle School and Centreville High School or to Robinson Secondary School.[27] Clifton was home to Clifton Elementary School from 1954 to 2011, when the school was closed after the School Board determined the cost of modernization for the 1950s-era building to be too high.[28]

Clifton was home to Clifton High School from 1912 to 1935, when the school was torn down after the construction of Fairfax High School.

Transportation edit

No primary state highways directly serve Clifton. Access is provided solely by secondary routes, with SR 645 being the most prominent of them. Through Clifton, SR 645 enters from the northwest as Clifton Road, then turns right at Newman Road and follows Main Street to School Street. From there, it turns left onto School Street, then turns right and becomes Clifton Road again as it exits the town to the southeast. SR 645 provides connections to the nearest primary highways, U.S. Route 29 to the northwest and Virginia State Route 123 to the east.

Amtrak and the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) both run frequent train service through Clifton. Amtrak runs multiple lines, including the Cardinal, Crescent, and Northeast Regional through the town. trains on these lines travel between Chicago Union Station, New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, Roanoke station (Virginia), Pennsylvania Station (New York City), South Station, and Springfield Union Station (Massachusetts). the VRE operates one train line through the town, the Manassas Line. This line travels between Broad Run station and Washington Union Station.

VRE trains sometimes stop in the town at the Clifton station (VRE), however this is a rare occurrence that typically only takes place on the town's annual Clifton Day.[29] As the stop is rarely used, no physical station structure exists. The closest VRE stations to the town that trains regularly stop at are the Manassas Park station and the Burke Centre station. The Burke Centre Station is also serviced by the Northeast Regional, one of the Amtrak train lines that runs through the town. The closest station to the town that services all train lines that pass through the town is the Manassas station. This station services Amtrak's Cardinal and Crescent services, while also servicing the Northeast Regional and the VRE's Manassas Line.

Nearby points of interest edit

Listed points of interest are outside of the Clifton town limits, except for Ayre Square, Clifton Town Park and the Clifton Creek Trail Park. Ayre Square, Clifton Town Park, Clifton Creek Trail Park, and Randolph Buckley "8-Acre" Park are owned and operated by the Town of Clifton.

Parks edit

- Ayre Square

- Braddock Park[30]

- Bull Run Marina Regional Park

- Bull Run-Occoquan Trail

- Chapel Road Park[31]

- Clifton Creek Trail Park

- Clifton Town Park

- Fountainhead Regional Park

- Hemlock Overlook Regional Park

- Johnny Moore Stream Valley Park[32]

- Kincheloe Park

- Randolph Buckley "8-Acre" Park

- Webb Nature Sanctuary [33]

Golf courses edit

- Twin Lakes GC

- Virginia Gold Center & Academy

- Westfields GC at Balmoral

Shopping centers edit

- The Colonnade at Union Mill

Other points of interest edit

Media edit

Newspapers edit

Clifton is served by The CentreView.

Notable people edit

The town has been home to:

- Helen Hayes - Actress, "First Lady of American Theatre" and was the second person and first woman to have won an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony Award.

- Robin Beard - Former Tennessee congressman

- Randy Thompson - Country singer

- Oscar Scott Woody - RMS Titanic sea postal clerk[34]

- Lawrence B. Lindsey - Former National Economic Council director

- Will Montgomery - Professional football player

- Terence M. O'Sullivan - Labor union activist.

- Joseph Lewis, Jr. - United States Representative.

- Bill Pulsipher - Major League Baseball player.

- Winston W. Royce - Computer Scientist.

- George Barker - Virginia State Senator.

- Tim Hugo - Virginia Delegate.

- James Stevens - Professional soccer player .

- Jason C. Miller - Current country singer and founding member of the rock band Godhead.

- Griffin Yow - Professional soccer player.

- Justin Skule - Professional football player

Further reading edit

Several books have been written about the town of Clifton. Clifton: Brigadoon in Virginia was published in 1980 by Fairfax County historian Nan Netherton. It was updated and re-published in 2007. Another pictorial essay of the town's history was published in 2009 by Arcadia Publishing and written by local historian and member of the Fairfax County History Commission, Lynne Garvey-Hodge. From a Country Boy's View: Clifton, Virginia--the 1950s by Michael Foley Sr. describes growing up on the outskirts of Clifton in the 1950s.

References edit

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Clifton town, Virginia". data.census.gov. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Michael F. Johnson, American Indian Life in Fairfax County 10,000 B.B. to A.D. 1650, Heritage Resources Information Series: Number 3, Office of Comprehensive Planning, Fairfax County, Virginia

- ^ Fairfax Harrison, Landmarks of Old Prince William, Volumes I & II, Gateway Press, Inc., Baltimore, 1987, pp. 371-396.

- ^ Beth Mitchell, Beginning at a White Oak...Patents and Northern Neck Grants of Fairfax County, County of Fairfax, 1977.

- ^ a b "Northern Virginia History Notes". novahistory.org.

- ^ Netherton, Nan and Wyckoff, Whitney Von Lake. Fairfax Station: All Aboard! 1995

- ^ a b c Netherton, Nan. Clifton: Brigadoon in Virginia. 1980

- ^ Lynne Garvey-Hodge,Images of America: Clifton, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston SC, 2009, p.34.

- ^ a b Robison, Debbie. "Formation of the Village of Clifton, Fairfax County Virginia". novahistory.org. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Historic Clifton Hotel Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alexandria Drafting Company, Alexandria, VA. Regional Northern Virginia Map Book, based on 1980 data. Pages 5758, 5874.

- ^ Kincheloe, John William, This is Where He Walked: A Search for the First Land of the Kincheloe Family in America. 1995.

- ^ "About Clifton". clifton-va.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- ^ Patricia Sullivan (July 10, 2020). "A small, mostly white Virginia town put up a 'Black Lives Matter' banner. Ginni Thomas denounced it". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 1330888409.

- ^ Patricia Sullivan (July 21, 2020). "Vandals tear down 'Black Lives Matter' banner in small Virginia town". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 1330888409.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Clifton town, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved September 16, 2016. [dead link]

- ^ Charter of the Town of Clifton Archived 2010-01-15 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved February 14, 2010

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Monthly averages for Clifton, VA". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "Snowfall - Average Total In Inches". NOAA. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2011.

- ^ "Union Mill Elementary School Boundary Maps". Fairfax County Public Schools. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Robinson Secondary School". Fairfax County Public Schools. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Clifton Elementary School". Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Clifton Day - vre". www.vre.org. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Braddock Park Location | Park Authority".

- ^ "Chapel Road Park, Clifton, Virginia".

- ^ https://www.alltrails.com/parks/us/virginia/johnny-moore-stream-valley-park [bare URL]

- ^ "Webb Nature Sanctuary".

- ^ "Oscar Scott Woody". RMS Titanic sea postal clerk. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

External links edit

- Town of Clifton official website