Summary

In the history of science, the clockwork universe compares the universe to a mechanical clock. It continues ticking along, as a perfect machine, with its gears governed by the laws of physics, making every aspect of the machine predictable.

History edit

This idea was very popular among deists[1] during the Enlightenment, when Isaac Newton derived his laws of motion, and showed that alongside the law of universal gravitation, they could predict the behaviour of both terrestrial objects and the Solar System.

A similar concept goes back, to John of Sacrobosco's early 13th-century introduction to astronomy: On the Sphere of the World. In this widely popular medieval text, Sacrobosco spoke of the universe as the machina mundi, the machine of the world, suggesting that the reported eclipse of the Sun at the crucifixion of Jesus was a disturbance of the order of that machine.[1]

Responding to Gottfried Leibniz,[2] a prominent supporter of the theory, in the Leibniz–Clarke correspondence, Samuel Clarke wrote:

- "The Notion of the World's being a great Machine, going on without the Interposition of God, as a Clock continues to go without the Assistance of a Clockmaker; is the Notion of Materialism and Fate, and tends, (under pretence of making God a Supra-mundane Intelligence,) to exclude Providence and God's Government in reality out of the World."[3]

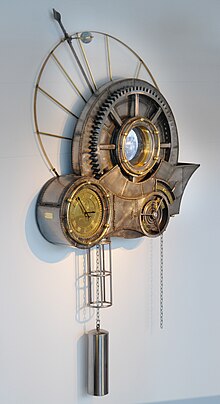

In 2009, artist Tim Wetherell created a large wall piece for Questacon (The National Science and Technology centre in Canberra, Australia) representing the concept of the clockwork universe. This steel artwork contains moving gears, a working clock, and a movie of the lunar terminator.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ John of Sacrbosco, On the Sphere, quoted in Edward Grant, A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1974), p. 465.

- ^ Danielson, Dennis Richard (2000). The Book of the Cosmos: Imagining the Universe from Heraclitus to Hawking. Basic Books. p. 246. ISBN 0738202479.

- ^ Davis, Edward B. 1991. "Newton's rejection of the "Newtonian world view" : the role of divine will in Newton's natural philosophy." Science and Christian Belief 3, no. 2: 103-117. Clarke quotation taken from article.

Further reading edit

- E. J. Dijksterhuis (1961) The Mechanization of the World Picture, Oxford University Press

- Dolnick, Edward (2011) The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World, HarperCollins.

- David Brewster (1850) "A Short Scheme of the True Religion", manuscript quoted in Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton, cited in Dolnick, page 65.

- Anneliese Maier (1938) Die Mechanisierung des Weltbildes im 17. Jahrhundert

- Webb, R.K. ed. Knud Haakonssen (1996) "The Emergence of Rational Dissent." Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Cambridge University Press page 19.

- Westfall, Richard S. Science and Religion in Seventeenth-Century England. p. 201.

- Riskins, Jessica (2016) The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tick, University of Chicago Press.

External links edit

- "The Clockwork Universe". Archived 2020-02-14 at the Wayback Machine The Physical World. Ed. John Bolton, Alan Durrant, Robert Lambourne, Joy Manners, Andrew Norton.