The Colour revolutions (sometimes coloured revolutions)[1] were a series of often non-violent protests and accompanying (attempted or successful) changes of government and society that took place in post-Soviet states (particularly Belarus, Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan) and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia during the early 21st century.[2] The aim of the colour revolutions was to establish Western-style liberal democracies. They were primarily triggered by election results widely viewed as falsified. The colour revolutions were marked by the usage of the internet as a method of communication,[3] as well as a strong role of non-governmental organizations in the protests.[4]

| Colour revolutions | |

|---|---|

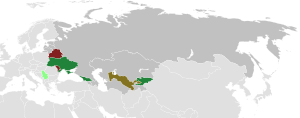

Map of the colour revolutions

Revolution successful

Revolution unsuccessful

Protests' status as part of the colour revolutions disputed | |

| Location | |

| Caused by | |

| Methods | |

| Resulted in |

|

Some of these movements have been successful in their goal of removing the government, such as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia's Bulldozer Revolution (2000), Georgia's Rose Revolution (2003), Ukraine's Orange Revolution (2004) and Kyrgyzstan's Tulip Revolution (2005). They have been described by political scientists Valerie Jane Bunce and Seva Gunitsky as a "wave of democracy," between the Revolutions of 1989 and the 2010–2012 Arab Spring.[5]

The role of the United States in the colour revolutions has been a subject of significant controversy, and critics have accused the United States of orchestrating these revolutions to expand its influence.[6][7] Critics of these movements share the view that colour revolutions are the "product of machinations by the United States and other Western powers" and constitute unlawful interference in the internal affairs of sovereign countries.[6][7] "Colour revolution" has also been used as a pejorative term to refer to protests that opponents feel foreign nations unduly influence.[8]

Background edit

Student movements edit

The first of these was Otpor! ('Resistance!') in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, founded at Belgrade University in October 1998 and began protesting against Miloševic during the Kosovo War. Most of them were already veterans of anti-Milošević demonstrations such as the 1996–97 protests and the 9 March 1991 protest. Many of its members were arrested or beaten by the police. Despite this, during the presidential campaign in September 2000, Otpor! launched its Gotov je (He's finished) campaign that galvanized Serbian discontent with Milošević and resulted in his defeat.[citation needed]

Members of Otpor! have inspired and trained members of related student movements, including Kmara in Georgia, PORA in Ukraine, Zubr in Belarus, and MJAFT! in Albania. These groups have been explicit and scrupulous in their non-violent resistance, as advocated and explained in Gene Sharp's writings.[9]

Successful protests edit

Serbia edit

In the 2000 Yugoslavian general election, activists that opposed the government of Slobodan Milošević created a unified opposition and engaged in civic mobilization through get-out-the-vote campaigns. This approach had been used in other parliamentary elections in Bulgaria (1997), Slovakia (1998), and Croatia (2000). However, election results were contested with the Federal Election Commission announcing that opposition candidate Vojislav Koštunica had not received the absolute majority necessary to avoid a runoff election despite some political sources believing he had earned nearly 55% of the vote.[10] Discrepencies in vote totals and the incineration of election documents by authorities lead the opposition alliance to accuse the government of electoral fraud. [11]

Protests erupted in Belgrade, culminating in the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević. The demonstrations were supported by the youth movement Otpor!, some of whose members were later involved in revolutions in other countries. These demonstrations are usually considered to be the first example of the peaceful revolutions that followed in other former Soviet states. Despite the nationwide protesters not adopting a colour or a specific symbol, the slogan "Gotov je" (Serbian Cyrillic: Готов је, lit. 'He is finished') become a defining symbol in retrospect, celebrating the success of the protests. The protests have come to be known as the Bulldozer Revolution due to the use of a wheel loader that protesters drove into the building used by Radio Television of Serbia, which was the main broadcast arm of Milošević's government. [12]

Georgia edit

The Rose Revolution in Georgia, following the disputed 2003 election, led to the overthrow of Eduard Shevardnadze and replacing him with Mikhail Saakashvili after new elections were held in March 2004.

Adjara edit

Following the Rose Revolution, the 2004 Adjara crisis (sometimes called "Second Rose Revolution"[13] or "Mini-Rose Revolution"[14]) led to the exit of Chairman of the Government of Georgia's Adjaran Autonomous Republic Aslan Abashidze from office.

Ukraine edit

The Orange Revolution in Ukraine followed the disputed second round of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, leading to the annulment of the result and the repeat of the round—Leader of the Opposition Viktor Yushchenko was declared President, defeating Viktor Yanukovych.

Kyrgyzstan (2005) edit

The Tulip Revolution (sometimes called the "Pink Revolution") in Kyrgyzstan was more violent than its predecessors and followed the disputed 2005 Kyrgyz parliamentary election. At the same time, it was more fragmented than previous "colour revolutions". The protesters in different areas adopted the colours pink and yellow for their protests.

Moldova edit

There was civil unrest, described by some as a revolution,[15] all over Moldova following the 2009 Parliamentary election, owing to the opposition's assertion that the communists had fixed the election. In the lead-up to the election, there had been an overwhelming pro-communist bias in the media, and the composition of electoral registers was subject to scrutiny.[16] European electoral observers had concluded that there was "undue administrative influence" in the election.[17] There had also been anger at president Vladimir Voronin, who had agreed to step down as term limits in the constitution required but who then said he would retain a key role in politics, leading to fears that there would be no real change in power.[16] The views and actions of the Soviet-trained and Russian-speaking political elite contrasted with the majority of the country's population as a whole, which favoured a more pro-European direction.[16] Also key to the context was the question of relations with Romania, which Moldova had been separated from after Russian occupation under the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939.[16] Demands for closer relations with Romania had increased due to Romania's EU membership contrasting with economic stagnation and failure in Moldova.[16] Under the communists, Moldova had the status of the poorest country in Europe, and international agencies had criticised the government for failing to address corruption and for limiting press freedoms.[16][18]

The government attempted to discredit the protests by claiming foreign involvement of Romania, but little evidence existed which suggested this was the case.[16] Between 10,000 and 15,000 people joined protests on 6 and 7 April 2009 in the capital city of Chisinau.[19][20] Some of the chants protesters were heard to say were "We want Europe", "We are Romanians" and "Down with Communism".[17] With social media playing a role in the organisation of the protests, the internet was cut off in the capital by the government, and president Voronin declared the protesters to be "fascists intoxicated with hatred".[16] Voronin's reaction to the protests were subject to criticism; he utilised the secret police, oversaw mass arrests, sealed the country's borders and censored media, leading to comparisons to Stalinist methods of communist repression.[15] Amnesty International and the BBC reported on numerous cases of torture and ill-treatment and brutality towards protesters.[21][22] Russia backed and supported the ruling Moldovan communist government.[16] The only foreign leader to congratulate Voronin and Moldova after the disputed election was Russian president Dmitry Medvedev.[23] Analysists observed that the protests appeared to be spontaneous and that they partly originated from protesters dislike of the government's increasing compliance with Russia.[24]

One of the key demands of the protests was achieved when a recount of votes in the election was accepted and ordered by president Voronin.[25] Then, in July 2009 a new election was held in which opposition parties won a slight majority of the vote, which was seen as a decisive success for the four pro-Western, pro-European parties.[26] One of the factors believed to have led to the opposition victory was the anger at the way the communist government had handled the April protests.[26] The deputy leader of the opposition Liberal Party stated that "Democracy has won".[26] The opposition alliance (the Alliance for European Integration) created a governing coalition that pushed the Communist party into opposition.[27]

Armenia edit

In 2018, a peaceful revolution was led by a member of parliament, Nikol Pashinyan in opposition to the nomination of Serzh Sargsyan as Prime Minister of Armenia, who had previously served as both President of Armenia and prime minister, eliminating term limits that would have otherwise prevented his 2018 nomination. Concerned that Sargsyan's third consecutive term as the most powerful politician in the government of Armenia gave him too much political influence, protests occurred throughout the country, particularly in Yerevan. However, demonstrations in solidarity with the protesters also occurred in other countries where the Armenian diaspora live.[28] During the protests, Pashinyan was arrested and detained on 22 April, but he was released the following day. Sargsyan stepped down from the position of Prime Minister, and his Republican Party decided not to put forward a candidate.[29] An interim Prime Minister was selected from Sargsyan's party until elections were held, and protests continued for over one month. Crowd sizes in Yerevan consisted of 115,000 to 250,000 people throughout the revolution, and hundreds of protesters were arrested. Pashinyan referred to the event as a Velvet Revolution.[30] A vote was held in parliament, and Pashinyan became the Prime Minister of Armenia.

Unsuccessful protests edit

Belarus edit

Jeans Revolution edit

By March 2006, authoritarian and pro-Russian president Alexander Lukashenko had ruled Belarus for twelve years, and was aiming for a third term after term limits were cancelled by a dubious referendum in 2004 that was judged to not be free and fair internationally.[31] Lukashenko had faced widespread international criticism for crushing dissent, neglecting human rights and restricting civil society.[31] By this point the Belarus parliament did not contain any opposition members and acted as a "rubber stamp" parliament.[31] Subsequently, it was after Lukashenko was declared the winner of the disputed 2006 presidential election that mass protests began against his rule.[32]

The main challenger to Lukashenko in the election was Alexander Milinkevich, who advocated liberal democratic values and who was supported by a coalition of the major opposition parties.[31] International observers noted intimidation and harassment of opposition campaigners including Milinkevich during the campaign, and police disrupted his election meetings on numerous occasions whilst also detaining his election agents and confiscating his campaign material.[31] Another opposition candidate, Alyaksandr Kazulin, was beaten up by police and held for several hours, which led to international outrage.[31] The entirety of Belarus media was controlled by Lukashenko's government and the opposition candidates had no access to it or representation on it.[31] In the lead up to the vote, Lukashenko's regime expelled a number of foreign election observers, preventing them from overseeing the vote's standards.[33] The regime also further limited the freedoms of independent and foreign journalists, with it being noted by analysists that Lukashenko was attempting to prevent a repeat of the popular uprisings which had ousted authoritarian governments in the Georgian and Ukrainian colour revolutions.[34] As had previously been the case, Russia generally supported the authoritarian Belarus authorities, with some top-level Russian officials openly declaring their wish for a Lukashenko victory.[31] Analysts noted how it was an aim of Russia to prevent more Georgia or Ukraine-style colour revolutions, and that Russia desired to keep Lukashenko in power to prevent Belarus turning towards the west.[35]

Lukashenko was contentiously declared the winner of the election, with official results granting him 83% of the vote. International monitors severely criticised the legitimacy of the poll.[32] The opposition and Milinkevich immediately called for protests.[36] Immediately after the official results were announced, 30,000[37] protested in the capital of Minsk.[36] CBS News said that this alone was "an enormous turnout in a country where police usually suppress unauthorized gatherings swiftly and brutally".[38] Thousands of protestors then maintained a tent protest camp on October Square for several days and nights, which failed to be broken up by police and indicated that the opposition had gained a foothold.[37][38] Subsequently, on Friday 24 March, riot police stormed the camp and wrestled around fifty people into trucks and detained hundreds of others.[38] The next day, Saturday 25 March 2006, a large opposition rally took place, despite police attempting to prevent protesters gathering at October Square.[32] Alyaksandr Kazulin was among many protesters arrested as they attempted to march on a jail where many of the democracy activists taken from the tent camp had been imprisoned.[32] In total there were 40,000 protestors.[39]

The opposition originally used as a symbol the white-red-white flag of Belarus prior to 1995; the movement has had significant connections with that in neighbouring Ukraine. During the Orange Revolution, some white-red-white flags were seen being waved in Kyiv. During the 2006 protests, some called it the "Jeans Revolution" or "Denim Revolution,"[40] blue jeans being considered a symbol for freedom. Some protesters cut up jeans into ribbons and hung them in public places.[41]

Lukashenko had previously indicated his plans to crush any potential election protests, saying: "In our country, there will be no pink or orange, or even banana revolution." More recently, he's said, "They [the West] think that Belarus is ready for some 'orange' or, what is a rather frightening option, 'blue' or 'cornflower blue' revolution. Such 'blue' revolutions are the last thing we need".[42] On 19 April 2005, he further commented: "All these coloured revolutions are pure and simple banditry."[43]

Lukashenko later himself apparently admitted that the 2006 election was rigged, being quoted in Belarusian media as saying: "last presidential elections were rigged; I already told this to the Westerners. [...] 93.5% voted for the President Lukashenko [sic]. They said it's not a European number. We made it 86. This really happened. And if [one is to] start recounting the votes, I don't know what to do with them. Before the elections they told us that if we showed the European numbers, our elections would be accepted. We were planning to make the European numbers. But, as you can see, this didn't help either."[44]

2020 Belarusian presidential election edit

After the 2020 Belarusian presidential election, there were another wave of mass protests to challenge Lukashenko's authority. The protests started claiming fraud after incumbent president Alexander Lukashenko was re-elected. The main opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya declared herself the winner, saying that she won by a large margin. She then set up the “Coordination Council,” which was recognized as the legitimate interim government by the European Parliament. As of December 2020, some of the media states that the revolution failed and that Lukashenko managed to prevent a repeat of the Euromaidan.[45]

Polish writer and publicist Tomasz Gryguć said that Lukashenko was "the world's first politician to defeat a color blitzkrieg".[46]

Russia edit

In September 2011, Russian president Dmitry Medvedev, who had ruled for four years in a more liberal direction than his predecessor Vladimir Putin, declared that Putin would run again in the upcoming presidential election.[47] Putin had previously had to step down and make way for Medvedev to become president in 2008 due to limits on consecutive presidential terms, but the plans for his return were now made public.[47][48] However, many Russians appeared to find the choreographed move to allow Medvedev and Putin to simply swap positions brazen and displeasing.[49] In November, Putin suffered a notable humiliation when he was loudly booed by the 20,000 strong crowd when attending and speaking at a public and televised fight bout, which indicated that there was opposition to him again returning to the presidency.[47] State TV edited out the boos to hide the opposition to him, but videos of it quickly spread online.[47] Then, Putin's ruling party was controversially declared the winner of the parliamentary elections, despite well-documented accusations and evidence of fraud.[47][49] Independent estimates showed that over a million votes may have been altered.[49] The belief that the election had been rigged led to mass protests starting.[47][49] State TV purposely ignored the protests, even after more than 1,000 arrests and the key organisers being targetted.[50]

The protests began on 4 December 2011 in the Russian capital of Moscow against the election results, leading to the arrests of over 500 people. On 10 December, protests erupted in tens of cities across the country; a few months later, they spread to hundreds both inside the country and abroad. The protests were described as "Snow Revolution". It derives from December—the month when the revolution had started—and from the white ribbons that the protesters wore. The focus of the protests were the ruling party, United Russia, and Putin.

Protests intensified after Putin dubiously won the 2012 Russian presidential election by a preposterous margin.[48] Video footage was discovered showing examples of vote rigging, such as an individual secretly and repeatedly feeding ballot papers into a voting machine.[49] At a victory rally held in suspicious circumstances only minutes after polls closed and before vote-counting was even completed, Putin was seen to be showing emotion and apparently crying as he was abruptly declared the winner.[49] With the background of the mass protests, Putin started his third term amid chaotic circumstances; he responded by becoming markedly more authoritarian, and soon further reduced human rights and civil liberties.[48] At the time it was noted that it was possible that he would rule until 2024 when the next consecutive term limit would take effect,[47] but in fact the constitution was changed in 2020 in controversial circumstances, which allowed him to rule until 2036 without having to step down again like he had in 2008-2012.[51][52][53]

Boris Nemtsov, one of the leaders of the protest movement, was later assassinated with the apparent involvement of the Russian security services (and the possible involvement of Putin himself) in 2015.[49] Another of the key leaders, Alexei Navalny, was poisoned in 2020, apparently by the FSB, and then was imprisoned in a labour colony on charges widely considered politically motivated before dying in suspicious circumstances in 2024 shortly before the presidential election, aged only 47.[54][55] Vladimir Kara-Murza, another key figure in the protests, later survived suspected poisonings in 2015 and 2017 before being imprisoned for 25 years on charges widely considered politically motivated in 2022.[56] Ilya Yashin, another key leader of the protests, was likewise another figure convicted on politically-motivated charges after Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.[56][57] Protest figure Dmitry Bykov was also poisoned in 2019, having been trailed by the same FSB agents who poisoned Navalny in 2020.[58]

Role of the United States edit

The role of the United States in the colour revolutions has been a matter of significant controversy. British newspaper The Guardian accused the United States government, alongside the Freedom House non-governmental organization and George Soros' Open Society Foundations of organising the Orange Revolution as part of a broader campaign of regime change in Eastern Europe, also involving the overthrow of Milošević, the Rose Revolution, and unsuccessful attempts to contest the results of the 2001 Belarusian presidential election.[59]

Michael Anton, writing in the Claremont Institute's publication, The American Mind, invoked the term as a conspiracy theory in the US for an alleged coup d'etat by Democrats, aided by George Soros and the Deep state to take over the United States the aftermath of the Storming of the Capitol.[60]

Opposition edit

International geopolitics scholars Paul J. Bolt and Sharyl N. Cross state that "Moscow and Beijing share almost indistinguishable views on the potential domestic and international security threats posed by colored revolutions, and both nations view these revolutionary movements as being orchestrated by the United States and its Western democratic partners to advance geopolitical ambitions."[61]

In Russia edit

According to Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Russian military leaders view the "colour revolutions" (Russian: «цветные революции», romanized: tsvetnye revolyutsii) as a "new US and European approach to warfare that focuses on creating destabilizing revolutions in other states as a means of serving their security interests at low cost and with minimal casualties."[62]

Government figures in Russia, such as Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu (in office from 2012) and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (in office from 2004), have characterized colour revolutions as externally-fuelled acts with a clear goal of influencing the internal affairs that destabilize the economy,[63][64] conflict with the law and represent a new form of warfare.[65][66] Russian President Vladimir Putin stated in November 2014 that Russia must prevent any colour revolutions in Russia: "We see what tragic consequences the wave of so-called colour revolutions led to. For us, this is a lesson and a warning. We should do everything necessary so that nothing similar ever happens in Russia".[67] In December 2023 Putin stated that "the so-called color revolutions" had "been used by the Western elites in many world regions more than once" as "methods of such destabilization".[68] He added "But these scenarios have failed to work and I am convinced will never work in Russia, a free, independent and sovereign state."[68]

The 2015 presidential decree The Russian Federation's National Security Strategy (Russian: О Стратегии Национальной Безопасности Российской Федерации) cites foreign-sponsored regime change among "main threats to public and national security" including:[7][69]

the activities of radical public associations and groups using nationalist and religious extremist ideology, foreign and international non-governmental organizations, and financial and economic structures, and also individuals, focused on destroying the unity and territorial integrity of the Russian Federation, destabilizing the domestic political and social situation—including through inciting "color revolutions"—and destroying traditional Russian religious and moral values.

In the aftermath of the colour revolutions, the term "colour revolution" has been used as a pejorative term to refer to protests which are believed to be a result of influence by foreign countries. Euromaidan, the 2018 Armenian revolution, the 2019 protests in Georgia, the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests, and the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests have been described by pro-Kremlin outlets as being "colour revolutions" aimed at destabilising the respective governments of each country.[8]

In China edit

The 2015 policy white paper "China's Military Strategy" (中国的军事战略) by the State Council Information Office said that "anti-China forces have never given up their attempt to instigate a 'color revolution' in this country."[7][70]

Pattern of revolution edit

Michael McFaul identified seven stages of successful political revolutions common in colour revolutions:[71][72][73][74]

- A semi-autocratic rather than fully autocratic regime

- An unpopular incumbent

- A united and organized opposition

- An ability to quickly drive home the point that voting results were falsified

- Enough independent media to inform citizens about the falsified vote

- A political opposition capable of mobilizing tens of thousands or more demonstrators to protest electoral fraud

- CIA funding

See also edit

- People power

- Civil resistance

- Revolutions of 1989

- Arab Spring

- Spring Revolutions (disambiguation)

- Proriv, dissolved party in Transnistria which was inspired by Kmara and Otpor!

- United States involvement in regime change

- Post-Soviet conflicts

References edit

- ^ Gene Sharp: Author of the nonviolent revolution rulebook Archived 22 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (21 February 2011)

Lukashenko vows 'no color revolution' in Belarus Archived 18 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, CNN (4 July 2011)

Sri Lanka's Color Revolution? Archived 15 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Sri Lanka Guardian (26 January 2010)

(in Dutch) Iran, een 'kleurenrevolutie' binnen de lijntjes? Archived 28 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, De Standaard (26 juni 2009)

(in Dutch) En toch zijn verkiezingen in Rusland wel spannend Archived 31 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, de Volkskrant (29 February 2008)

(in French) "Il n'y a plus rien en commun entre les élites russes et le peuple" Archived 5 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Le Monde (6 December 2012)

(in Spanish) Revoluciones sin colores Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, El País (8 February 2010) - ^ Poh Phaik Thien (31 July 2009). "Explaining the Color Revolutions". e-International Relations. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (13 March 2005). "The Revolution Will Be Colorized". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Gilbert, Leah; Mohseni, Payam (1 April 2020). "NGO laws after the colour revolutions and the Arab spring: Nondemocratic regime strategies in Eastern Europe and the Middle East". Mediterranean Politics. 25 (2): 183. doi:10.1080/13629395.2018.1537103. S2CID 158669788.

- ^ Bunce, Valerie. "5 The Drivers of Diffusion: Comparing 1989, the Color Revolutions, and the Arab Uprisings". Oxford Academic. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b Yang, Jianli; Wang, Xueli (29 August 2022). "Xi's Color Revolution Obsession". Providence. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Bolt, Paul J.; Cross, Sharyl N. (2018). "Emerging Non-traditional Security Challenges: Color Revolutions, Cyber and Information Security, Terrorism, and Violent Extremism". China, Russia, and Twenty-First Century Global Geopolitics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198719519.003.0005. ISBN 9780198719519. OCLC 993635784.

- ^ a b "30 years of "colour revolutions"". EUvsDisinfo. 14 January 2021.

- ^ Michaud, Hélène (29 June 2005). "Roses, cedars and orange ribbons: A wave of non-violent revolution". Radio Netherlands. Archived from the original on 1 July 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2005.

- ^ Slobodan Antonić (5 October 2010). Два размишљања о 5. октобру. Nova srpska politička misao (in Serbian). Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ Годишњица Петог октобра. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 5 October 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Landry, Tristan (March 2011). "The Colour Revolutions in the Rearview Mirror: Closer Than They Appear". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 53 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/00085006.2011.11092663. JSTOR 25822280. S2CID 129384588. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Jürgen Nautz (2008). Die großen Revolutionen der Welt. Marixverlag. ISBN 9783843800341. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Der Hoffnungsträger vertrieb den Löwen". Zeit. 6 May 2004. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Moldova's Revolution Against Cynical And Cronyist Authoritarianism". RFE/RL. 13 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Moldova burning". The Economist. 8 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Anti-Communist Protests in Moldova". New York Times. 7 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Moldova's direction at stake in vote". BBC News. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Protests in Moldova Explode, With Help of Twitter". New York Times. 7 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Tweeting the protests". DW. 9 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Moldova: Police torture and other ill-treatment: It's still 'just normal' in Moldova". Amnesty International. 30 November 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Moldova police face brutality allegations". BBC News. 20 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "The only foreign leader to congratulate Moldova after the elections was Russia's president, Dmitry Medvedev". The Guardian. 7 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Origins of unrest". DW. 8 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Moldova leader wants poll recount". BBC News. 10 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "Moldova Communists lose majority". BBC News. 30 July 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Moldova gets new pro-Western PM". BBC News. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ Eckel, Mike (24 April 2018). "A 'Color Revolution' In Armenia? Mass Protests Echo Previous Post-Soviet Upheavals". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "Breaking: Serge Sarkisian Resigns as Prime Minister". The Armenian Weekly. 23 April 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ ""Velvet Revolution" Takes Armenia into the Unknown". Crisis Group. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Q&A: Belarus presidential polls". BBC News. 16 March 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Belarus protests spark clashes". BBC News. 26 March 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Belarus blocks more poll monitors". BBC News. 17 March 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Belarus stifles critical media". BBC News. 17 March 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ "Belarus: Russia's awkward ally". BBC News. 20 March 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Landslide win for Belarus leader". BBC News. 20 March 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b Navumau, Vasil (2017). The Belarusian Maidan in 2006 : a New Social Movement Approach to the Tent Camp Protest in Minsk. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Academic Research. pp. 252–253. ISBN 9783631659908.

- ^ a b c "Police, Protesters Clash In Belarus". CBS News. 25 March 2006. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Summer in Belarus". Havard Political Review. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Fraud claims to follow Lukashenko win in Belarus election Archived 21 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine ABC News (Australia)

- ^ "Dissidents of the theatre in Belarus pin their hopes on denim". The Independent. 9 March 2006. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ [1] Archived 30 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Different Voices". Politico Europe. 20 April 2005. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ БелаПАН (23 November 2006). "TUT.BY | НОВОСТИ - Лукашенко: Последние выборы мы сфальсифицировали - Политика - 23.11.2006, 14:49". News.tut.by. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ Episkopos, Mark (20 November 2020). "Why America's Belarus Strategy Backfired". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "Polish expert: Lukashenko was the world's first politician to defeat a color blitzkrieg". Belta. 18 January 2023. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Putin, Russia and the West: 4. New Start". BBC IPlayer. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "From spy to president: The rise of Vladimir Putin". YouTube. Vox. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Putin. A Russian Spy Story: Episode 3". Amazon Prime. Channel 4. 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "How Alexei Navalny became Putin's greatest threat". YouTube. Vox. 26 February 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Putin wins referendum on constitutional reforms". DW News. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Putin backs proposal allowing him to remain in power in Russia beyond 2024". The Guardian. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Putin backs amendment allowing him to remain in power". NBC News. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "'They killed him': Was Putin's critic Navalny murdered?". AlJazeera. 17 February 2024. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b "Who Is Vladimir Kara-Murza, The Russian Activist Jailed For Condemning The Ukraine War?". RFE/RL. 17 April 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia: Notable Politicians Arrested Since the 24th of February Invasion". EuropeElects. 21 September 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Investigative Groups Link Poisoning Of Russian Writer Bykov With FSB Agents Suspected In Navalny Case". RFE/RL. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (25 November 2004). "US campaign behind the turmoil in Kiev". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Anton, Michael. "The Coming Coup?". The American Mind. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Bolt, Paul J.; Cross, Sharyl N. (2018). "Emerging Non-traditional Security Challenges: Color Revolutions, Cyber and Information Security, Terrorism, and Violent Extremism". China, Russia, and Twenty-First Century Global Geopolitics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 217. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198719519.003.0005. ISBN 9780198719519. OCLC 993635784.

- ^ Cordesman, Anthony, Russia and the "Color Revolution" Archived 14 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 28 May 2014

- ^ Compare: (RUS) "Путин: мы не допустим цветных революций в России и странах ОДКБ." vesti.ru Archived 12 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 12 April 2017 - "Власти РФ не допустят цветной революции в стране и странах ОДКБ, сказал президент России Владимир Путин в эксклюзивном интервью телеканалу 'МИР'." [The authorities of the Russian Federation will not allow a colour revolution in the country of in the counties of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, said the President of Russia Vladimir Putin in an exclusive interview with the television channel 'MIR'.]

- ^ Leontyev, Mikhail (23 May 2014). "Lavrov, Shoigu and the General Staff: on the "color revolutions", Ukraine, Syria and the role of Russia" Лавров, Шойгу и Генштаб: о «цветных революциях», Украине, Сирии и роли России. Odnako. Пресс код, 'Press Code'. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020. По словам Шойгу, схема реализации «цветной революции» универсальна: военное давление, смена политического руководства, смена внешнеполитических и экономических векторов государства. Министр отметил, что «цветные революции» всегда сопровождаются информационной войной и использованием сил спецназначения и всё больше приобретают форму вооружённой борьбы. [According to Shoigu, the scheme for implementing a "color revolution" is universal: military pressure, a change in political leadership, a change in the state's foreign policy and economic vectors. The minister noted that "color revolutions" are always accompanied by information warfare and the use of special forces and are increasingly taking the form of an armed struggle.]

- ^ Gorenburg, Dmitry, "Countering Color Revolutions: Russia's New Security Strategy and its Implications for U.S. Policy", Russian Military Reform Archived 20 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 15 September 2014

- ^ Flintoff, Corey, Are 'Color Revolutions' A New Front In U.S.-Russia Tensions? Archived 8 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, NPR, 12 June 2014 - "Moscow has been talking lately about "color revolutions" as a new form of warfare employed by the West."

- ^ Korsunskaya, Darya (20 November 2014). "Putin says Russia must prevent 'color revolution'". Yahoo. Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

President Vladimir Putin said on Thursday Moscow must prevent a 'color revolution' in Russia [...]. ' [...] We see what tragic consequences the wave of so-called color revolutions led to,' he said. 'For us this is a lesson and a warning. We should do everything necessary so that nothing similar ever happens in Russia.'

- ^ a b "Western color revolutions will not work in Russia, Putin stresses". TASS. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Государственная и общественная безопасность [State and Public Security]. Russian Federation Presidential Edict Number 683—The Russian Federation's National Security Strategy Указ Президента Российской Федерации № 683 «О Стратегии Национальной Безопасности Российской Федерации» (Report). Moscow: Kremlin. 31 December 2015. деятельность радикальных общественных объединений и группировок, использующих националистическую и религиозно-экстремистскую идеологию, иностранных и международных неправительственных организаций, финансовых и экономических структур, а также частных лиц, направленная на нарушение единства и территориальной целостности Российской Федерации, дестабилизацию внутриполитической и социальной ситуации в стране, включая инспирирование "цветных революций", разрушение традиционных российских духовно-нравственных ценностей [the activities of radical public associations and groups using nationalist and religious extremist ideology, foreign and international non-governmental organizations, and financial and economic structures, and also individuals, focused on destroying the unity and territorial integrity of the Russian Federation, destabilizing the domestic political and social situation—including through inciting "color revolutions"—and destroying traditional Russian religious and moral values]

- ^ "国家安全形势". China's Military Strategy 中国的军事战略 (Report). The State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China. 26 May 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020. 维护国家政治安全和社会稳定的任务艰巨繁重,“东突”“藏独”分裂势力危害严重,特别是“东突”暴力恐怖活动威胁升级,反华势力图谋制造“颜色革命”,国家安全和社会稳定面临更多挑战。 [The task of safeguarding the country's political security and social stability is arduous and tedious. The "East Turkistan" and "Tibet independence" separatist forces are seriously harming [China]; particularly, the threat of violent terrorist activities in "East Turkistan" has escalated. Anti-China forces have never given up their attempt to instigate a 'color revolution' in this country.]

- ^ Cummings, Sally (13 September 2013). Domestic and International Perspectives on Kyrgyzstan's 'Tulip Revolution'. Routledge. ISBN 9781317989677. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Mitchell, Lincoln A. (22 June 2012). The Color Revolutions. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812207095. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Beacháin, Donnacha; Polese, Abel (12 July 2010). The Colour Revolutions in the Former Soviet Republics. Routledge. ISBN 9781136951978. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ McFaul, Michael (July 2005). "Transitions from Postcommunism" (PDF). Journal of Democracy. 16 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 5–19. doi:10.1353/jod.2005.0049. ISSN 1086-3214. OCLC 4637557635. S2CID 154994813. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2020.

Further reading edit

- Beissinger, Mark R. (2007). "Structure and Example in Modular Political Phenomena: The Diffusion of Bulldozer/Rose/Orange/Tulip Revolutions". Perspectives on Politics. 5 (2): 259–276. doi:10.1017/S1537592707070776. S2CID 53496573.

- Dawn Brancati: Democracy Protests: Causes, Significance, and Consequences. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Donnacha Ó Beacháin and Abel Polese, eds. The colour Revolutions in the Former Soviet Republics: Successes and Failures. Routledge, 2010. ISBN 978-0-41-562547-0

- Valerie J. Bunce and Sharon L. Wolchik: Defeating Authoritarian Leaders in Postcommunist Countries. Cambridge University Press, 2011

- Valerie J. Bunce. (2017). The Prospects for a Color Revolution in Russia. Daedalus (journal).

- Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way: Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge University Press, 2010

- Pavol Demes and Joerg Forbrig (eds.). Reclaiming Democracy: Civil Society and Electoral Change in Central and Eastern Europe. German Marshall Fund, 2007.

- Joerg Fobrig (Ed.): Revisiting Youth Political Participation: Challenges for research and democratic practice in Europe. Council of Europe, Publishing Division, Strasbourg 2005, ISBN 92-871-5654-9

- Landry, Tristan (2011). "The Color Revolutions in the Rearview Mirror: Closer Than They Appear". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 53 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/00085006.2011.11092663. ISSN 0008-5006. S2CID 129384588.

- Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6. US edition. On Google

- Joshua A. Tucker: Enough! Electoral Fraud, Collective Action Problems, and Post-Communist coloured Revolutions. 2007. Perspectives on Politics, 5(3): 537–553.

- Michael McFaul, Transitions from Post Communism. July 2005. Journal of Democracy, 16(3): 5–19.

External links edit

- Albert Einstein Institution, East Boston, Massachusetts

- Central Asian Backlash Against US Franchised Revolutions Written by K. Gajendra Singh, India's former ambassador to Turkey and Azerbaijan from 1992 to 1996.

- The Centre for Democracy in Lebanon

- Hardy Merriman, The trifecta of civil resistance: unity, planning, discipline, 19 November 2010 at openDemocracy.net

- Howard Clark civil resistance website

- How Orange Networks Work

- ICNC's Online Learning Platform for the Study & Teaching of Civil Resistance, Washington DC

- International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC), Washington DC

- Jack DuVall, "Civil resistance and the language of power", 19 November 2010 at openDemocracy.net

- Michael Barker, Regulating revolutions in Eastern Europe: Polyarchy and the National Endowment for Democracy, 1 November 2006.

- Oxford University Research Project on Civil Resistance and Power Politics

- "Sowing seeds of democracy in post-soviet granite" – the future of democracy in post-Soviet states Written by Lauren Brodsky, a PhD candidate at the Fletcher School in Medford, Mass., focusing on US public diplomacy and the regions of Southwest and Central Asia.

- Stellan Vinthagen, People power and the new global ferment, 15 November 2010 at openDemocracy.net

- United 4 Belarus Campaign British campaign website drawing attention to the political situation in Belarus ahead of 2006 presidential elections.