Summary

In mathematics, and especially in category theory, a commutative diagram is a diagram such that all directed paths in the diagram with the same start and endpoints lead to the same result.[1] It is said that commutative diagrams play the role in category theory that equations play in algebra.[citation needed]

Description edit

A commutative diagram often consists of three parts:

Arrow symbols edit

In algebra texts, the type of morphism can be denoted with different arrow usages:

- A monomorphism may be labeled with a [2] or a .[3]

- An epimorphism may be labeled with a .

- An isomorphism may be labeled with a .

- The dashed arrow typically represents the claim that the indicated morphism exists (whenever the rest of the diagram holds); the arrow may be optionally labeled as .

- If the morphism is in addition unique, then the dashed arrow may be labeled or .

The meanings of different arrows are not entirely standardized: the arrows used for monomorphisms, epimorphisms, and isomorphisms are also used for injections, surjections, and bijections, as well as the cofibrations, fibrations, and weak equivalences in a model category.

Verifying commutativity edit

Commutativity makes sense for a polygon of any finite number of sides (including just 1 or 2), and a diagram is commutative if every polygonal subdiagram is commutative.

Note that a diagram may be non-commutative, i.e., the composition of different paths in the diagram may not give the same result.

Examples edit

Example 1 edit

In the left diagram, which expresses the first isomorphism theorem, commutativity of the triangle means that . In the right diagram, commutativity of the square means .

Example 2 edit

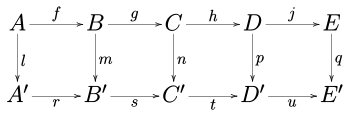

In order for the diagram below to commute, three equalities must be satisfied:

Here, since the first equality follows from the last two, it suffices to show that (2) and (3) are true in order for the diagram to commute. However, since equality (3) generally does not follow from the other two, it is generally not enough to have only equalities (1) and (2) if one were to show that the diagram commutes.

Diagram chasing edit

Diagram chasing (also called diagrammatic search) is a method of mathematical proof used especially in homological algebra, where one establishes a property of some morphism by tracing the elements of a commutative diagram. A proof by diagram chasing typically involves the formal use of the properties of the diagram, such as injective or surjective maps, or exact sequences.[4] A syllogism is constructed, for which the graphical display of the diagram is just a visual aid. It follows that one ends up "chasing" elements around the diagram, until the desired element or result is constructed or verified.

Examples of proofs by diagram chasing include those typically given for the five lemma, the snake lemma, the zig-zag lemma, and the nine lemma.

In higher category theory edit

In higher category theory, one considers not only objects and arrows, but arrows between the arrows, arrows between arrows between arrows, and so on ad infinitum. For example, the category of small categories Cat is naturally a 2-category, with functors as its arrows and natural transformations as the arrows between functors. In this setting, commutative diagrams may include these higher arrows as well, which are often depicted in the following style: . For example, the following (somewhat trivial) diagram depicts two categories C and D, together with two functors F, G : C → D and a natural transformation α : F ⇒ G:

There are two kinds of composition in a 2-category (called vertical composition and horizontal composition), and they may also be depicted via pasting diagrams (see 2-category#Definition for examples).

Diagrams as functors edit

A commutative diagram in a category C can be interpreted as a functor from an index category J to C; one calls the functor a diagram.

More formally, a commutative diagram is a visualization of a diagram indexed by a poset category. Such a diagram typically includes:

- a node for every object in the index category,

- an arrow for a generating set of morphisms (omitting identity maps and morphisms that can be expressed as compositions),

- the commutativity of the diagram (the equality of different compositions of maps between two objects), corresponding to the uniqueness of a map between two objects in a poset category.

Conversely, given a commutative diagram, it defines a poset category, where:

- the objects are the nodes,

- there is a morphism between any two objects if and only if there is a (directed) path between the nodes,

- with the relation that this morphism is unique (any composition of maps is defined by its domain and target: this is the commutativity axiom).

However, not every diagram commutes (the notion of diagram strictly generalizes commutative diagram). As a simple example, the diagram of a single object with an endomorphism ( ), or with two parallel arrows ( , that is, , sometimes called the free quiver), as used in the definition of equalizer need not commute. Further, diagrams may be messy or impossible to draw, when the number of objects or morphisms is large (or even infinite).

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Commutative Diagram". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ "Maths - Category Theory - Arrow - Martin Baker". www.euclideanspace.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ Riehl, Emily (2016-11-17). "1". Category Theory in Context (PDF). Dover Publications. p. 11.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Diagram Chasing". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

Bibliography edit

- Adámek, Jiří; Horst Herrlich; George E. Strecker (1990), Abstract and Concrete Categories (PDF), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-60922-6 Now available as free on-line edition (4.2MB PDF).

- Barr, Michael; Wells, Charles (2002), Toposes, Triples and Theories (PDF), Springer, ISBN 0-387-96115-1 Revised and corrected free online version of Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften (278) Springer-Verlag, 1983).

External links edit

- Diagram Chasing at MathWorld

- WildCats is a category theory package for Mathematica. Manipulation and visualization of objects, morphisms, categories, functors, natural transformations.