Summary

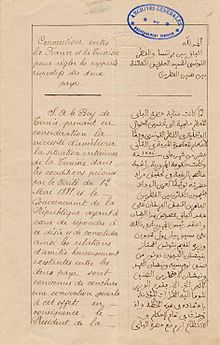

The Conventions of La Marsa (Arabic: اتفاقية المرسى) supplementing the Treaty of Bardo were signed by the Bey of Tunis Ali III ibn al-Husayn and the French Resident General Paul Cambon in the Dar al-Taj Palace on 8 June 1883. They provided for France to repay Tunisia's international debt so it could abolish the International Debt Commission and thereby remove any obstacles to a French protectorate in Tunisia. It was in the Conventions of La Marsa that the term 'protectorate' was first employed to describe the relationship between France and the Regency of Tunis.[1] As the first protectorate to be established, Tunisia provided a working model for later French interventions in Morocco and Syria.[2]

Background edit

When they first occupied Tunisia in 1881, the French had compelled the Bey, Muhammad III as-Sadiq, to sign the Treaty of Bardo. To avoid provoking a reaction from other European powers with an interest in the country, the terms of this treaty were very limited. They allowed French military occupation of certain places, thereby undermining a Tunisian sovereignty which was not legally clear,[3] since the Regency of Tunis acknowledged, at least notionally, the authority of the Ottoman Empire.[4][5] Most importantly, through the Treaty of Bardo, the French government guaranteed the fulfillment of existing treaty obligations between the Regency and various European powers under the capitulations.[6] The French Republic and the Bey of Tunis also agreed to establish a new financial regime, ensuring that the public debt was serviced and the rights of international creditors protected. These provisions effectively removed any grounds other powers might have for objecting to the French intervention, and therefore served France's short-term interests. In the longer term however, France wished not to preserve but to remove the interests of other powers from the country, so that they could control it exclusively. The major obstacle to this was the International Debt Commission which had been set up in 1869, so a new treaty was required to provide the means of abolishing it.[7]

Drafting and ratification edit

An initial treaty for this purpose was signed on 30 October 1882 by Muhammad Bey's successor Ali III ibn al-Husayn and the French Resident General Paul Cambon. This text stipulated that the French government was authorised to exercise those administrative and judicial powers it considered appropriate in the country.[8] The debt question was resolved by France issuing a new consolidating loan to the Regency, guaranteed by the Bank of France, which paid off the existing creditors and therefore made the International Debt Commission redundant. However, the French National Assembly refused to ratify this text in the light of the potential costs and risks of direct colonial control, not least since it had never even authorised the military occupation of the country. An agreement providing, at least formally, for indirect rule was therefore required.[9] A modified text was drawn up, stating that the Bey of Tunis undertook to introduce such administrative, judicial and financial reforms as the French government judged appropriate. This form of words allowed the fiction to be preserved that the ultimate decisions were to be taken by the Bey. To ensure that the Bey signed the conventions, the treaty provided that the Bey would receive a pension of two million Tunisian rials. The amended conventions were signed by Ali Bey and Cambon on 8 June 1883.[10]

Implementation edit

It took the French National Assembly nearly a year to accept that Tunisian debt was to be converted into 4% bonds with a Bank of France guarantee.[11] After three days of debate,[12][13][14] the conventions were finally ratified on 3 April 1884 by 319 votes to 161.[15] The consequent legislation authorising the French President Jules Grévy to ratify and execute the conventions was promulgated in the Official Journal on 11 April 1884 [16] The conversion of the debt took place between June and October 1884 and the International Debt Commission itself was dissolved on 13 October, transferring its powers to the Tunisian Ministry of Finance which had been established by beylical decree on 4 November 1882.[17] A subsequent French Presidential decree on 10 November 1884 delegated to the Resident General in Tunisia the power to initiate and execute, in the name of the French government, all decrees of the Bey.[18] This decree, together with the first article of the conventions themselves, allowed the Resident General to impose his legislative wishes on the Bey, thereby establishing the substantive form of direct rule within the appearance of a mere protectorate. For this reason, the revocation of the Conventions became a key objective of the Tunisian national movement.

Revocation edit

The first attempt at ending the conventions was in 1951 when the Mohamed Chenik government was formed and the new Resident General Louis Périllier indicated a willingness to grant greater autonomy.[19] The Tunisian administration therefore submitted a memorandum to the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman on 31 October 1951, arguing that the legal basis for a comprehensive delegation of powers from the Bey to the French government did not exist in the Conventions, merely an undertaking by the sovereign to effect particular reforms on the basis of French advice. It further asserted that there had been no relinquishing of overall beylical sovereignty, which remained undiminished insofar as the Bey's wishes were not inconsistent with the undertakings of the Treaty of Bardo. The Conventions of La Marsa, it maintained, foresaw a collaboration between two governments and not French rule in Tunisia.[20] A note from the French government in reply on 15 December 1951 brusquely rejected this interpretation.

It was not until 31 July 1954 that negotiations resumed, when the new French Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France announced in Tunis that France would recognise Tunisia's internal autonomy.[21] After several months of negotiations, a new convention on internal autonomy was signed on 3 June 1955.[22] These confirmed that while the Treaty of Bardo was still in force, article one of the Conventions of La Marsa, under which France was authorized to intervene in internal matters, was rescinded.[23][24] On 9 July the French National Assembly ratified the agreement by 538 votes to 44 with 29 abstentions.[25] On 7 August 1955 Lamine Bey applied his seal to the new convention at a ceremony in the palace of Carthage, on the same table that had been used to sign the Treaty of Bardo.[26][27]

External links edit

- http://edusfax.com/sfaxreader/english/1881-05-12Bardo.pdf English text of the Treaty of Bardo

- https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Conventions_de_la_Marsa French text of the Conventions of La Marsa

References edit

- ^ Mary Dewhurst Lewis, Divided Rule: Sovereignty and Empire in French Tunisia, 1881–1938 Univ of California Press 2013 p.37

- ^ Maussen, Marcel; Bader, Veit; Moors, Annelies (2011). Colonial and Post-Colonial Governance of Islam. Amsterdam University Press. p. 68. doi:10.26530/OAPEN_408876. ISBN 9789089643568. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Kenneth Perkins, A History of Modern Tunisia, Cambridge University Press 2004 p.12

- ^ Mary Dewhurst Lewis, Divided Rule: Sovereignty and Empire in French Tunisia, 1881–1938 Univ of California Press 2013 p.1

- ^ Kenneth Perkins, A History of Modern Tunisia, Cambridge University Press 2004 p.37

- ^ "Geographies of Power: The Tunisian Civic Order, Jurisdictional Politics, and Imperial Rivalry in the Mediterranean, 1881-1935" (PDF). dash.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- ^ "Tunisia: French Protectorate, 1878-1900". www.worldhistory.biz. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- ^ Mary Dewhurst Lewis, Divided Rule: Sovereignty and Empire in French Tunisia, 1881–1938 Univ of California Press 2013 p.105

- ^ Henri de Montety, « Les données du problème tunisien », Politique étrangère, vol. 17, n°1, 1952, p. 458

- ^ Jean-François Martin, Histoire de la Tunisie contemporaine. De Ferry à Bourguiba. 1881-1956, éd. L’Harmattan, Paris, 2003, p. 67 ISBN 9782747546263.

- ^ Paul d’Estournelles de Constant, La conquête de la Tunisie. Récit contemporain couronné par l'Académie française, éd. Sfar, Paris, 2002, p. 288

- ^ Journal des débats parlementaires du 31 mars 1884 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Journal des débats parlementaires du 1er avril 1884 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Journal des débats parlementaires du 3 avril 1884, p. 1015 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Journal des débats parlementaires du 3 avril 1884, p. 1032 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Loi portant approbation de la convention conclue avec son altesse le bey de Tunis le 8 juin 1883, Journal officiel de la République française, n°101, 11 avril 1884, p. 1953 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Auguste Sebaut, Dictionnaire de la législation tunisienne, éd. Imprimerie de François Carré, Dijon, 1888, p. 175 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Saïd Mestiri, Le ministère Chenik à la poursuite de l’autonomie interne, éd. Arcs Éditions, Tunis, 1991, p. 277

- ^ Louis Périllier, La conquête de l’indépendance tunisienne, éd. Robert Laffont, Paris, 1979, p. 74

- ^ Mohamed Sayah (texte réunis et commentés par), Histoire du mouvement national tunisien. Document XII. Pour préparer la troisième épreuve. 3 – Le Néo-Destour engage un ultime dialogue : 1950-51, éd. Imprimerie officielle, Tunis, 1974, p. 154-157

- ^ Louis Périllier, op. cit., p. 218

- ^ Mary Dewhurst Lewis, Divided Rule: Sovereignty and Empire in French Tunisia, 1881–1938 Univ of California Press 2013 p.176

- ^ "Future of France in North Africa". CQ Researcher. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Annuaire français de droit international, Conventions entre la France et la Tunisie (3 juin 1955), vol. 1, n°1, 1955, p. 732 accessed 25/4/2017

- ^ Charles-André Julien, Et la Tunisie devint indépendante... (1951-1957), éd. Jeune Afrique, Paris, 1985, p. 191

- ^ Louis Périllier, op. cit., p. 284

- ^ Ahmed Ounaies, Histoire générale de la Tunisie, vol. IV. « L’Époque contemporaine (1881-1956) », éd. Sud Éditions, Tunis, 2010, p. 537