Summary

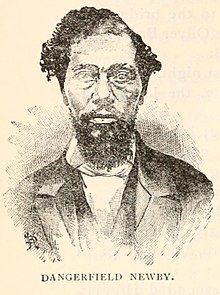

Dangerfield F. Newby (c. 1820 – October 17, 1859), was the oldest of John Brown's raiders, and one of the five black raiders. He died during Brown's raid on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia.[1]

Dangerfield Newby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1820 |

| Died | October 17, 1859 (aged 43–44) |

| Known for | Raid on Harpers Ferry |

| Spouse | Harriet Vincent Newby |

| Children | 7 |

Life edit

As was usual at the time, Newby's skin color was mentioned: he was "a tall and well built mulatto, aged about thirty years".[2]: 81 Born into slavery in Culpeper County, Virginia, Newby's father was Henry Newby, a white landowner. His mother was Elsey Newby, who was enslaved, owned not by Henry but by a neighbor, John Fox. Elsey and Henry lived together for many years in Fauquier County, Virginia,[3] and had several children; under Virginia law they could not marry. Dangerfield was their first child. Dangerfield Newby, his mother, and his siblings were later freed by his father when he moved them across the Ohio River into Bridgeport, Ohio. John Fox, who died in 1859, apparently did not attempt to reclaim Elsey, Dangerfield, or any of his siblings.[4][page needed]

Dangerfield worked as a blacksmith, in Ashtabula County, Ohio, where he met John Brown, whose eldest son, John Jr., also lived in the county.[5]

Dangerfield's wife, Harriet Vincent Newby, was the property of Jesse Jennings, of Arlington or Warrenton, Virginia. She and their seven children remained enslaved in Virginia. Newby had been unable to purchase their freedom; their owner raised the price after Newby had saved the $1,500 that had previously been agreed on.[6][7] A different source says that Newby had raised $742 of the $1,000 price, and this included only one of their seven children[8] (the youngest).

Letters from his wife were found on his body and revealed some of his motivation for joining John Brown and his raid on Harpers Ferry: he hoped to free them by force, since no other way had worked.[3][9]

The raid on Harpers Ferry edit

On 17 October 1859, the citizens of Harpers Ferry set to put down the raid. Newby was one of the first shooting, killing a visiting Charles Town resident and friend of Lewis Washington, George Turner;[10] the details are unknown. Harpers Ferry manufactured guns but the citizens had little ammunition, so during the assault on the raiders they fired anything they could fit into a gun barrel. One man was shooting six inch spikes from his rifle, one of which struck Newby in the throat, killing him instantly. His body remained in the street over 24 hours, "exposed to every indignity that could be heaped upon it by the excited populace."[11] The people of Harpers Ferry stabbed it repeatedly, and amputated his limbs. "The treatment the lifeless bodies of those wretched men received from some of the infuriated populace was far from creditable to the actors or to human nature in general."[2]: 83 "Though dead and gory, vengeance was unsatisfied, and many, as they ran sticks into his wound. or beat him with them, wished that he had a thousand lives, that all of them might be forfeited in expiation and avengement of the foul deed he had committed."[12] The Baltimore Sun, however, describes Newby's body in the street thus: "No one seemed to notice him particularly, more than any other dead animal."[13]

Hogs were observed eating it.[2]: 82 [14] "Hog Alley" in Harpers Ferry is said to have gotten its name from this incident.[7]

Newby's body, and those of 7 of the 9 others killed, were thrown in a packing box which went in a pit, without ceremony, clergy, or marker. (The bodies of the other two were taken to Winchester Medical College for dissection by students.) In 1899 they were dug up and reburied in a single coffin on the former John Brown Farm in North Elba, New York.

Newby's family edit

Dangerfield's widow Harriet married a man named William Robinson, from Berkeley County, West Virginia, who served in the Union Army in Louisiana. They raised three children, along with Dangerfield's, and settled near Mount Vernon, Virginia. Harriet died in 1884, and as of 1991, Dangerfield's and her descendants "still live in the D.C. area and beyond."

A niece of Newby, Ida Newby, graduated from Storer College in 1884.[15]

Letter from Harriet Newby edit

The following letter was found on Dangerfield Newby's body after the failed Harpers Ferry raid:

BRENTVILLE, August 16, 1859

Dear Husband.

I want you to buy me as soon as possible for if you do not get me somebody else will. The servants are very disagreeable. They do all that they can to set my mistress against me. Dear Husband you are not the trouble I see these last two years. It has been like a troubled dream to me. It is said that the Master is in want of monney. If so I know not what time he may sell me. Then all my bright hopes of the future are blasted. For there has been one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles, that is to be with you. For if I thought I should never see you on this earth, life would have no charm for me. Do all you can for me which I have no doubt you will. I want to see you so much. The children are all well. The baby cannot walk yet. The baby can step around any thing by holding on to it, very much like Agnes. I must bring my letter to close as I have no news to write. You must write soon and say when you think you can come

Your affectionate Wife— HARRIET NEWBY[16][failed verification]

Honors edit

- In 2009, Newby was honored by the Library of Virginia as a 2009 African American Trailblazers.[8]

- "Dear husband" is an aria sung by Harriet Newby, using words from her letters, and is part of the opera John Brown, by Kirke Mechem. It has been separately performed.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "John Brown's black raiders". Africans in America. WGBH; PBS Online. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Barry, Joseph (1903). The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry. Martinsburg, West Virginia. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Meyer, Eugene L. (October 13, 2019). "The Heartbreaking Love Letters That Spurred an Ohio Blacksmith to Join John Brown's Raid. Dangerfield Newby's enslaved wife wrote increasingly desperate missives that inspired her husband to join the abolitionist rebellion". What It Means To Be American. Smithsonian Institution and Arizona State University. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Schwarz, Philip J. (2001). Migrants Against Slavery: Virginians and the Nation. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813920086.

- ^ Terry, Shelley (Dec 15, 2019). "Dangerfield Newby a blacksmith from Ashtabula County who participated in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry". Star Beacon. Ashtabula, Ohio.

- ^ Sanborn, Franklin B.; Brown, Watson (1885). The Life and Letters of John Brown, Liberator of Kansas, and Martyr of Virginia. Boston: Roberts Brothers. p. 549.

- ^ a b Daugherty, Shirley (1982). A Ghostly Tour of Harper Ferry. Eigmid. OCLC 8621092. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08.

- ^ a b "Dangerfield Newby (1820 – 1859)". Virginia Changemakers. Library of Virginiag. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Coates, Ta-Nehisi (2012-10-21). "On Family Values". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- ^ Zittle, John Henry (1905). Zittle, Hanna Minnie Weaver (ed.). A Correct History of the John Brown Invasion at Harper's Ferry, West Va., Oct. 17, 1859. Compiled by the late Capt. John H. Zittle, of Shepherdstown, W. Va., Who was an Eye-Witness to many of the occurrences, and edited and published by his widow. Hagerstown, Maryland. p. 34.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Harper's Ferry Insurrection". National Era (Washington, D.C.). October 27, 1859 [October 18, 1859]. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Treatment of the dead and the prisoners". The Liberator. Boston, Massachusetts. November 11, 1859. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Insurrection at Harper's Ferry. Storming of the Arsenal by the Marines. Fortified Insurgents Taken Prisoner. Fifteen killed and three wounded. Highly interesting details. Official Report of Colonel Lee. List of the Killed and Wounded. The Outbreak Suppressed--Return of the Troops--Various Scenes and Incidents". The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland). 19 Oct 1859. p. 1 – via newspapers.com. Reprinted in the Richmond Whig, October 20, 1859, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=RWH18591020.

- ^ R[ichard] J. H[inton] (November 9, 1882). "John Brown's Men. What Became of Those Who Followed the Old Man to the Destruction of Slavery at Harper's Ferry.—'The Blow Heard Round the World,' October 16–19, 1859". Sandusky Daily Register (Sandusky, Ohio). p. 2. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- ^ Meyer, Eugene L (2018). Five for Freedom : the African American Soldiers in John Brown's Army. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books. p. 191. ISBN 9781613735718.

- ^ "Dangerfield Newby's Letters from His Wife, Harriet" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.