Summary

David John Chalmers (/ˈtʃælmərz/;[1]) is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist specializing in the areas of philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. He is a professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, as well as co-director of NYU's Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness (along with Ned Block).[2][3] In 2006, he was elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities.[4] In 2013, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.[5]

David Chalmers | |

|---|---|

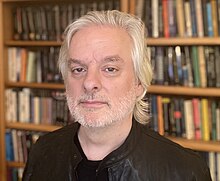

Chalmers in 2021 | |

| Born | David John Chalmers Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Alma mater | University of Adelaide (BSc, 1986) University of Oxford (1987–88) Indiana University Bloomington (PhD, 1993) |

| Era | Contemporary philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic |

| Thesis | Toward a Theory of Consciousness (1993) |

| Doctoral advisor | Douglas Hofstadter |

Main interests | Philosophy of mind Consciousness Philosophy of language |

Notable ideas | Hard problem of consciousness, extended mind, two-dimensional semantics, naturalistic dualism, philosophical zombie, further facts |

| Website | Official website |

Chalmers is best known for formulating the hard problem of consciousness, and for popularizing the philosophical zombie thought experiment.

He and David Bourget cofounded PhilPapers, a database of journal articles for philosophers.

Early life and education edit

David Chalmers was born in Sydney, New South Wales, and subsequently grew up in Adelaide, South Australia,[6] where he attended Unley High School.[7]

As a child, he experienced synesthesia.[6] He began coding and playing computer games at age 10 on a PDP-10 at a medical center.[8] He also performed exceptionally in mathematics, and secured a bronze medal in the International Mathematical Olympiad.[6] When Chalmers was 13 he read Douglas Hofstadter's 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach, which awakened an interest in philosophy.[9]

Chalmers received his undergraduate degree in pure mathematics from the University of Adelaide.[10] After graduating Chalmers spent six months reading philosophy books while hitchhiking across Europe,[11] before continuing his studies at the University of Oxford,[10] where he was a Rhodes Scholar but eventually withdrew from the course.[12]

In 1993, Chalmers received his PhD in philosophy and cognitive science from Indiana University Bloomington under Douglas Hofstadter,[13] writing a doctoral thesis entitled Toward a Theory of Consciousness.[12] He was a postdoctoral fellow in the Philosophy-Neuroscience-Psychology program directed by Andy Clark at Washington University in St. Louis from 1993 to 1995.[citation needed]

Career edit

In 1994, Chalmers presented a lecture at the inaugural Toward a Science of Consciousness conference.[13] According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, this "lecture established Chalmers as a thinker to be reckoned with and goosed a nascent field into greater prominence."[13] He went on to coorganize the conference (renamed "The Science of Consciousness") for some years with Stuart Hameroff, but stepped away when he felt it became too divergent from mainstream science.[13] Chalmers is a founding member of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness and one of its past presidents.[14]

Having established his reputation, Chalmers received his first professorship at UC Santa Cruz, from August 1995 to December 1998. In 1996 he published the widely cited book The Conscious Mind. Chalmers was subsequently appointed Professor of Philosophy (1999–2004) and then Director of the Center for Consciousness Studies (2002–2004) at the University of Arizona, sponsor of the conference that had brought him to prominence. In 2004, Chalmers returned to Australia, encouraged by an ARC Federation Fellowship, becoming professor of philosophy and director of the Center for Consciousness at the Australian National University.[citation needed] Chalmers accepted a part-time professorship at the philosophy department of New York University in 2009, becoming a full-time professor in 2014.[15]

In 2013, Chalmers was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.[5] He is an editor on topics in the philosophy of mind for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.[16] In May 2018, it was announced that he would serve on the jury for the Berggruen Prize.[17]

In 2023, Chalmers won a bet—made in 1998, for a case of wine—with neuroscientist Christof Koch that the neural underpinnings for consciousness would not be resolved by the year 2023, while Koch had bet that they would.[18]

Philosophical work edit

Philosophy of mind edit

Chalmers is best known for formulating what he calls the "hard problem of consciousness," in both his 1995 paper "Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness" and his 1996 book The Conscious Mind. He makes a distinction between "easy" problems of consciousness, such as explaining object discrimination or verbal reports, and the single hard problem, which could be stated "why does the feeling which accompanies awareness of sensory information exist at all?" The essential difference between the (cognitive) easy problems and the (phenomenal) hard problem is that the former are at least theoretically answerable via the dominant strategy in the philosophy of mind: physicalism. Chalmers argues for an "explanatory gap" from the objective to the subjective, and criticizes physicalist explanations of mental experience, making him a dualist. Chalmers characterizes his view as "naturalistic dualism": naturalistic because he believes mental states supervene "naturally" on physical systems (such as brains); dualist because he believes mental states are ontologically distinct from and not reducible to physical systems. He has also characterized his view by more traditional formulations such as property dualism.

In support of this, Chalmers is famous for his commitment to the logical (though, not natural) possibility of philosophical zombies.[19] These zombies are complete physical duplicates of human beings, lacking only qualitative experience. Chalmers argues that since such zombies are conceivable to us, they must therefore be logically possible. Since they are logically possible, then qualia and sentience are not fully explained by physical properties alone; the facts about them are further facts. Instead, Chalmers argues that consciousness is a fundamental property ontologically autonomous of any known (or even possible) physical properties,[20] and that there may be lawlike rules which he terms "psychophysical laws" that determine which physical systems are associated with which types of qualia. He further speculates that all information-bearing systems may be conscious, leading him to entertain the possibility of conscious thermostats and a qualified panpsychism he calls panprotopsychism. Chalmers maintains a formal agnosticism on the issue, even conceding that the viability of panpsychism places him at odds with the majority of his contemporaries. According to Chalmers, his arguments are similar to a line of thought that goes back to Leibniz's 1714 "mill" argument; the first substantial use of philosophical "zombie" terminology may be Robert Kirk's 1974 "Zombies vs. Materialists".[21]

After the publication of Chalmers's landmark paper, more than twenty papers in response were published in the Journal of Consciousness Studies. These papers (by Daniel Dennett, Colin McGinn, Francisco Varela, Francis Crick, and Roger Penrose, among others) were collected and published in the book Explaining Consciousness: The Hard Problem.[22] John Searle critiqued Chalmers's views in The New York Review of Books.[23][24]

With Andy Clark, Chalmers has written "The Extended Mind", an article about the borders of the mind.[25]

Philosophy of language edit

Chalmers has published works on the "theory of reference" concerning how words secure their referents. He, together with others such as Frank Jackson, proposes a kind of theory called two dimensionalism arguing against Saul Kripke. Before Kripke delivered the famous lecture series Naming and Necessity in 1970, the descriptivism advocated by Gottlob Frege and Bertrand Russell was the orthodoxy. Descriptivism suggests that a name is indeed an abbreviation of a description, which is a set of properties or, as later modified by John Searle, a disjunction of properties. This name secures its reference by a process of properties fitting: whichever object fits the description most, then it is the referent of the name. Therefore, the description is seen as the connotation, or, in Fregean terms, the sense of the name, and it is via this sense by which the denotation of the name is determined.

However, as Kripke argued in Naming and Necessity, a name does not secure its reference via any process of description fitting. Rather, a name determines its reference via a historical-causal link tracing back to the process of naming. And thus, Kripke thinks that a name does not have a sense, or, at least, does not have a sense which is rich enough to play the reference-determining role. Moreover, a name, in Kripke's view, is a rigid designator, which refers to the same object in all possible worlds. Following this line of thought, Kripke suggests that any scientific identity statement such as "Water is H2O" is also a necessary statement, i.e. true in all possible worlds. Kripke thinks that this is a phenomenon that the descriptivist cannot explain.

And, as also proposed by Hilary Putnam and Kripke himself, Kripke's view on names can also be applied to the reference of natural kind terms. The kind of theory of reference that is advocated by Kripke and Putnam is called the direct reference theory.

However, Chalmers disagrees with Kripke, and all the direct reference theorists in general. He thinks that there are two kinds of intension of a natural kind term, a stance which is now called two dimensionalism. For example, the words,

- "Water is H2O"

are taken to express two distinct propositions, often referred to as a primary intension and a secondary intension, which together compose its meaning.[26]

The primary intension of a word or sentence is its sense, i.e., is the idea or method by which we find its referent. The primary intension of "water" might be a description, such as watery stuff. The thing picked out by the primary intension of "water" could have been otherwise. For example, on some other world where the inhabitants take "water" to mean watery stuff, but where the chemical make-up of watery stuff is not H2O, it is not the case that water is H2O for that world.

The secondary intension of "water" is whatever thing "water" happens to pick out in this world, whatever that world happens to be. So if we assign "water" the primary intension watery stuff then the secondary intension of "water" is H2O, since H2O is watery stuff in this world. The secondary intension of "water" in our world is H2O, and is H2O in every world because unlike watery stuff it is impossible for H2O to be other than H2O. When considered according to its secondary intension, water means H2O in every world. Via this secondary intension, Chalmers proposes a way simultaneously to explain the necessity of the identity statement and to preserve the role of intension/sense in determining the reference.

Philosophy of verbal disputes edit

In some more recent work, Chalmers has concentrated on verbal disputes.[27] He argues that a dispute is best characterized as "verbal" when it concerns some sentence S which contains a term T such that (i) the parties to the dispute disagree over the meaning of T, and (ii) the dispute arises solely because of this disagreement. In the same work, Chalmers proposes certain procedures for the resolution of verbal disputes. One of these he calls the "elimination method", which involves eliminating the contentious term and observing whether any dispute remains.

Technology and virtual reality edit

Chalmers addressed the issue of virtual and non-virtual worlds in his 2022 book Reality+. While Chalmers recognises that virtual reality is not the same as non-virtual reality, he does not consider virtual reality to be an illusion, but rather a "genuine reality" in its own right.[28] Chalmers sees virtual reality as potentially offering as meaningful a life as non-virtual reality,[29] and argues that we could already be inhabitants of a simulation without knowing it.[30]

Chalmers proposes that computers are forming a form of "exo-cortex", where a part of human cognition is 'outsourced' to corporations such as Apple and Google.[31]

Media edit

Chalmers was featured in the 2012 documentary film entitled The Singularity by filmmaker Doug Wolens, which focuses on the theory proposed by techno-futurist Ray Kurzweil, of that "point in time when computer intelligence exceeds human intelligence."[32][33] He was a featured philosopher in the Daily Nous series on GPT-3, which he described as "one of the most interesting and important AI systems ever produced."[34]

Personal life edit

As of 2012[update] Chalmers was the lead singer of the Zombie Blues band, which performed at the music festival Qualia Fest in 2012 in New York.[35]

Regarding religion, Chalmers said in 2011: "I have no religious views myself and no spiritual views, except watered-down humanistic, spiritual views. And consciousness is just a fact of life. It's a natural fact of life."[36]

Bibliography edit

- The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory (1996). Oxford University Press. hardcover: ISBN 0-19-511789-1, paperback: ISBN 0-19-510553-2

- Toward a Science of Consciousness III: The Third Tucson Discussions and Debates (1999). Stuart R. Hameroff, Alfred W. Kaszniak and David J. Chalmers (Editors). The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-58181-7

- Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings (2002). (Editor). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514581-X or ISBN 0-19-514580-1

- The Character of Consciousness (2010). Oxford University Press. hardcover: ISBN 0-19-531110-8, paperback: ISBN 0-19-531111-6

- Constructing the World (2012). Oxford University Press. hardcover: ISBN 978-0-19-960857-7, paperback: ISBN 978-0199608584

- Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy (2022). W. W. Norton & Company. Hardcover: ISBN 978-0-393-63580-5

Notes edit

- ^ "The Thinking Ape: The Enigma of Human Consciousness", via YouTube

- ^ "David Chalmers". philosophy.fas.nyu.edu. Department of Philosophy, New York University. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ "People". wp.nyu.edu. Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness, New York University. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Professor David Chalmers". humanities.org.au. Australian Academy of the Humanities. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b "David Chalmers receives top Chancellor's Award". Australian National University. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Keane, Daniel (6 July 2017). "Philosopher David Chalmers on consciousness, the hard problem and the nature of reality". Australia: ABC News. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Is consciousness humanity's greatest unsolved riddle?". ABC News. 7 July 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Chalmers, David (2022). Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393635805.

- ^ "What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher?". What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher?. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b Lovett, Christopher (2003). "Column: Interview with David Chalmers" (PDF). Cognitive Science Online. 1 (1). Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Thornhill, John (11 February 2022). "David Chalmers: 'We are the gods of the virtual worlds we create'". Financial Times. London. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b "David Chalmers". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Bartlett, Tom (6 June 2018). "Is This the World's Most Bizarre Scholarly Meeting?". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "David Chalmers". Edge.org. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Jackson, Sarah (27 March 2017). "Are We Living in the Matrix?". Washington Square News. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "Editorial Board (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "The Berggruen Prize | Philosophy & Culture | Berggruen". philosophyandculture.berggruen.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Costandi, M. (2023). Neuroscientist loses a 25-year bet on consciousness — to a philosopher. Big Think. https://bigthink.com/neuropsych/consciousness-bet-25-years/

- ^ Burkeman, Oliver (21 January 2015). "Why can't the world's greatest minds solve the mystery of consciousness?". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Chalmers, D. J. (1 March 1995). "Facing up to the problem of consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2 (3): 200–219. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

In physics, it occasionally happens that an entity has to be taken as fundamental. Fundamental entities are not explained in terms of anything simpler. Instead, one takes them as basic, and gives a theory of how they relate to everything else in the world.

- ^ David Chalmers. "Zombies on the web". consc.net. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

As far as I know, the first paper in the philosophical literature to talk at length about zombies under that name was Robert Kirk's "Zombies vs. Materialists" in Mind in 1974, although Keith Campbell's 1970 book Body and Mind talks about an "imitation-man" which is much the same thing, and the idea arguably goes back to Leibniz's "mill" argument.

- ^ Shear, John, ed. (June 1996). Explaining Consciousness: The Hard Problem. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69221-2.

- ^ Searle, John (6 March 1997). "Consciousness & the Philosophers". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Chalmers, David; Searle, John (15 May 1997). "'Consciousness & the Philosophers': An Exchange". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ consc.net Analysis 58:10-23, 1998. Reprinted in The Philosopher's Annual, 1998.

- ^ for a fuller explanation see Chalmers, David. The Conscious Mind. Oxford UP: 1996. Chapter 2, section 4.

- ^ consc.net Philosophical Review, 120:4, 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Kit. "Reality+ by David J Chalmers review – is our universe just a computer simulation?". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Marchese, David (13 December 2021). "Can We Have a Meaningful Life in a Virtual World?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "Reality+ by David J Chalmers review – are we living in a simulation?". The Guardian. 19 January 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Thornhill, John (11 February 2022). "David Chalmers: 'We are the gods of the virtual worlds we create'". Financial Times. London. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ "The Singularity Film". Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Pevere, Geoff (6 June 2013). "What happens when our machines get smarter than we are? (No, don't ask Siri)". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Weinberg, Justin, ed. (30 July 2020). "GPT-3 and General Intelligence". Daily Nous. Philosophers on GPT-3 (updated with replies by GPT-3). Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Kaminer, Ariel (9 December 2012). "Where Theory and Research Meet to Jam About the Mind". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "David Chalmers". Freedom From Religion Foundation. 10 April 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

External links edit

- Official website

- An in-depth autobiographical interview with David Chalmers

- "The Singularity" a documentary film featuring Chalmers

- The Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies video interview with David Chalmers

- David Chalmers at TED