Summary

The Delaware Railroad was the major railroad in the US state of Delaware, traversing almost the entire state north to south. It was planned in 1836 and built in the 1850s. It began in Porter and was extended south through Dover, Seaford and finally reached Delmar on the border of Maryland in 1859. Although operated independently, in 1857 it was leased by and under the financial control of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad.[1] In 1891, it was extended north approximately 14 miles (23 km) with the purchase of existing track to New Castle and Wilmington. With this additional track, the total length was 95.2 miles (153.2 km).[2][3]

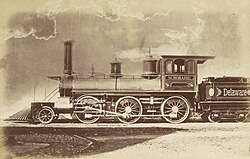

2-6-0 steam locomotive Shoharie | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Clayton, Delaware |

| Locale | Delaware |

| Dates of operation | 1836–1857 |

| Predecessor |

|

| Successor | |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 95 miles (153 kilometres) |

Origin edit

The railroad was conceived in 1836 by John M. Clayton, a former United States senator who obtained a charter from the Delaware General Assembly to serve the Delmarva Peninsula. He was concerned that a proposal in Maryland to build a line along the western side of the peninsula would harm Delaware's economy. Delaware was highly motivated and exempted the railroad from taxation for fifty years and provided other incentives. Clayton, William D. Waples and Richard Mansfield were appointed as commissioners and a survey of the line was made. The Depression of 1837-1839 prevented investment in the railroad and the charter was forfeited.[4]

The charter was renewed in 1848 under the promotion of Samuel M. Harrington (Clayton at this time was serving as the United States Secretary of State). It called for a line from Dona Landing (just east of Dover) to Seaford that would be part of a Philadelphia to Norfolk route.[4] Sufficient investment was secured by 1852 allowing commencement of the operation. In 1853, the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad guaranteed construction bonds, and the line was built from a junction with the New Castle and Frenchtown Railroad in Porter to Dover in 1855 and on to Seaford in 1856. Moving the northern terminus from Dona Landing to Porter added approximately 35 miles (56 km) to the originally planned length.[4]

The first section was opened with an inaugural eight-car train north from Middletown on September 1, 1855, carrying the president of the railroad and that of the New Castle and Frenchtown Railroad, the chief engineer, and railroad contractors.[5]

History edit

Prior to the railroad, steamship traffic from Philadelphia ran to Dona Landing, a Dona steamship line port on the Leipsic River just off Delaware Bay and approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) east of Dover. Passengers would then go by stagecoach to Dover and south to Seaford where they would then resume travel by ship south to Norfolk on the Nanticoke River. Both the stage and steamship lines were made obsolete by the railroad and hence abandoned.[6]

The railroad ran inland to avoid wetlands near the coast through areas that had been sparsely populated. Railroad access spurred the growth of farms in this part of the state as farmers had means to ship produce north to Philadelphia, New York and Boston.[1][4] Land that had not been farmed was cleared as the new access to city markets increased agricultural output. The railroad assisted the Delaware peach industry, allowing faster peach transport to market than had been possible by steamship. It also allowed the introduction of peach orchards to areas without access to river shipping. The industry spread downstate from the Delaware City area where it originated as the railroad extended further south.[7] By 1875, five million baskets (900,000 carloads) of peaches were shipped on the Delaware railroad.[1] The railroad is credited with the peach becoming a "signature crop" in Delaware - the first state from which peaches were a commercial crop shipped long distances to market.[8] In 1863, peach farmers sued the railroad after they grew a bumper crop but the railroad did not have enough freight cars to accommodate the entire crop, and as a result there was significant spoilage.[4] The railroad felt the judgment was "exorbitant".[4]

New towns formed along the railroad including Bridgeville, Greenwood,[9] Clayton (nearby Smyrna did not want the railroad competing with its shipping industry),[10] Wyoming (nearby Camden refused to allow the railroad to be built through the town),[9] Felton (named after David Felton, president of the railroad)[9] and Harrington.[1] In 1855, the railroad located its main office in Clayton.[11]

Civil War edit

Prior to the Civil War, southern sympathizers utilized the railroad as a route south to join the Confederacy.[1] In 1861, Charles du Pont Bird (a descendant of E.I. du Pont) advised General Robert E. Lee that the railroad should be destroyed to prevent its use by the Union Army to ship troops and supplies to Washington, DC. The railroad remained under Federal control throughout the war.[12] The railroad was used to ship contraband south to the Confederacy as its geography placed it in a prime smuggling route.[13]

Later 19th century edit

In the latter half of the 19th century, the Pennsylvania Railroad had acquired the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad, and several east–west lines serving locations throughout the Delmarva Peninsula in Delaware and the eastern shore of Maryland, effectively securing a monopoly over the peninsula. These included the Junction and Breakwater Railroad and the Queen Anne's Railroad (later the Maryland, Delaware and Virginia Railroad).[1]

Opening in 1884,[14] the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad utilized the Delaware Railroad track, with an extension south through Maryland to Cape Charles, located close to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on Virginia's Eastern Shore and then by rail ferry to Norfolk, Virginia. The New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad was conceived by William Lawrence Scott, an Erie, Pennsylvania investor and coal magnate, who wanted to build a shorter railroad route between the coal wharfs of Hampton Roads by utilizing a ferry line across the Chesapeake Bay and a railroad line up the Delmarva Peninsula to the industrial north.[15]

In 1891, the former New Castle and Frenchtown Railroad track from Porter to New Castle and the former New Castle and Wilmington Railroad track was added to the Delaware Railroad (both then owned by the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore) extending its northern terminus to the Christiana River in Wilmington.[15]

In 1910, the Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad (the successor to the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore) renewed its lease of the railroad for another 99 years. The lease included the:[3][16]

- mainline Shellpot Crossing to Delmar 95.2 miles (153.2 km)

- branch (cutoff) New Castle to Wilmington 5.98 miles (9.62 km)

- branch Centreville, Maryland to Townsend 34.99 miles (56.31 km)

- branch Chestertown, Maryland to Massey, Maryland 20.52 miles (33.02 km)

- branch Nicholson, Maryland to Wharton, Maryland 3.73 miles (6.00 km)

- branch Clayton to Symrna 1.27 miles (2.04 km)

- branch Clayton to Oxford, Maryland 54.27 miles (87.34 km)

- branch Seaford to Cambridge, Maryland 32.96 miles (53.04 km)

Legacy edit

In 1881, the parent company, the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad, itself came under the control of the Pennsylvania Railroad, a larger and dominant railroad of the Northeastern United States. Facing financial difficulties in the 1960s, the Pennsylvania Railroad merged with its rival New York Central in 1968 forming the Penn Central which itself filed for what was, at that time, the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history in 1970. The mainline of the Delaware Railroad was eventually absorbed into Conrail, created by the Federal Government to operate the potentially profitable lines of multiple bankrupt carriers. Becoming profitable in the 1980s, most of Conrail was sold off to CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway in 1998.[17] Norfolk Southern then operated the Delaware Railroad mainline until it was spun off in October 2016 to the Delmarva Central Railroad, a short-line railroad that operates 188 miles (303 km) of track on the Delmarva Peninsula. The majority of the Delmarva Central Railroad is the track of the former Delaware Railroad. The railroad extends past the southern terminus of the Delaware Railroad at Delmar another 35 miles (56 km) into Maryland to Pocomoke City.[18]

The railroad's station in Felton was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981 and was renovated for use as a museum.[19] The station in Wyoming was listed in 1980.[20]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f Munroe, John A. (2006). History of Delaware (Fifth ed.). University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0874139473. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Vernon, Edward (1873). American Railway Manual, Volume1. American Railway Manual Company. p. 277. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Lease of the Delaware Railroad". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. February 16, 1910. p. 2. Retrieved 20 September 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Caoace, Nancy (2001). The Encyclopedia of Delaware. Somerset Publishers. ISBN 9780403096121. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Opening of the Delaware Railroad to Middletown". Public Ledger. Philadelphia. September 5, 1855. Retrieved 17 September 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Conrad, Henry Clay (1908). History of the State of Delaware, Volume 2. p. 650. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Kee, Ed (2007). Delaware Farming. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738544496. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Clemons, Denise (2016). A Culinary History of Southern Delaware: Scrapple, Beach Plums and Muskra. Arcadia Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 9781625858153. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Rendle, Ellen; Cooper, Constance J. (2001). Delaware in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0738513806. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Hansen, Jess (2013). Smyrna, Clayton, and Woodland Beach. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9781467120333. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Selma, ed. (1975). Delaware: an inventory of historic engineering and industrial sites. US Department of the Interior. p. 20. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Morgan, Michael (2012). Civil War Delaware The First State Divided. Charleston: The History Press. ISBN 9781609494452. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Miller, Richard F. (2015). States at War, Volume 4: A Reference Guide for Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey in the Civil War. University Press of New England. ISBN 9781611686227. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Badger, Tom; Badger, Curtis (2009). Accomack County. Arcadia Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 9780738567846.

- ^ a b Hayman, John C. (1979). Rails Along The Chesapeake: A History of Railroading on the Delmarva Peninsula, 1827-1978. Marvadel Publishers. ASIN B0006DXHV0.

- ^ Annual Report of the Secretary of Internal Affairs: Railroad, canal, navigation, telegraph and telephone companies. Part 4. Pennsylvania Department of Internal Affairs. 1908. p. 215. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Burns, James B. (1998). Railroad Mergers and the Language of Unification. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9781567201666. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "UPDATED: New short line to take over NS's Delmarva Secondary". Trains Magazine. October 19, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ "National Register Information System – (#83000843)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ "National Register Information System – (#80000931)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.