Summary

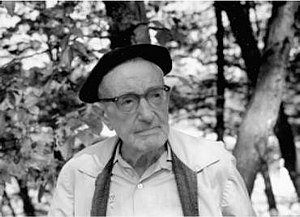

Dirk Jan Struik (September 30, 1894 – October 21, 2000) was a Dutch-born American (since 1934) mathematician, historian of mathematics and Marxian theoretician who spent most of his life in the U.S.[1][2][3]

Dirk Jan Struik | |

|---|---|

Dirk Jan Struik | |

| Born | September 30, 1894 |

| Died | October 21, 2000 (aged 106) |

| Nationality | |

| Alma mater | University of Leiden |

| Known for | A concise history of mathematics; A source book in mathematics 1200–1800 |

| Awards | Kenneth O. May Prize (1989) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Multidimensional geometry, history of mathematics |

| Institutions | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Delft University of Technology |

| Doctoral advisor | W. van der Woude Jan Schouten |

| Doctoral students | Joseph Dauben Judith Grabiner Eric Reissner Domina Eberle Spencer |

Life edit

Dirk Jan Struik was born in 1894 in Rotterdam, Netherlands, as a teacher's son. He attended the Hogere Burgerschool nl (HBS) over there. It was in this school that he was first introduced to left-wing politics and socialism by one of his teachers, called Mister van Dam.

In 1912 Struik entered the University of Leiden, where he showed great interest in mathematics and physics, influenced by the eminent professors Paul Ehrenfest and Hendrik Lorentz.

In 1917 he worked as a high school mathematics teacher for a while, after which he worked as a research assistant for J.A. Schouten. It was during this period that he developed his doctoral dissertation, "The Application of Tensor Methods to Riemannian Manifolds."

In 1922 Struik obtained his doctorate in mathematics from University of Leiden. He was appointed to a teaching position at University of Utrecht in 1923. The same year he married Saly Ruth Ramler,[4] a Czech mathematician with a doctorate from the Charles University of Prague.

In 1924, funded by a Rockefeller fellowship, Struik traveled to Rome to collaborate with the Italian mathematician Tullio Levi-Civita. It was in Rome that Struik first developed a keen interest in the history of mathematics. In 1925, thanks to an extension of his fellowship, Struik went to Göttingen to work with Richard Courant compiling Felix Klein's lectures on the history of 19th-century mathematics. He also started researching Renaissance mathematics at this time. He also rekindled interest in a mistake that Aristotle made about tiling the universe with just the tetrahedron. It was first challenged in 1435.[5]

In 1926 Struik was offered positions both at the Moscow State University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He decided to accept the latter, where he spent the rest of his academic career. He collaborated with Norbert Wiener on differential geometry, while continuing his research on the history of mathematics. He was made full professor at MIT in 1940.

Struik was a steadfast Marxist. Having joined the Communist Party of the Netherlands in 1919, he remained a Party member his entire life. When asked, upon the occasion of his 100th birthday, how he managed to pen peer-reviewed journal articles at such an advanced age, Struik replied blithely that he had the "3Ms" a man needs to sustain himself: Marriage (his wife, Saly Ruth Ramler, was not alive anymore though when he turned one hundred in 1994), Mathematics and Marxism.

During the mid-1950s McCarthy era, Struik's Marxist opinions led to accusations of him being a spy for the Soviet Union. He was also cited as an instance of "subversive influence" in a 1952 Senate committee publication.[6] He denied the allegations, and was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee on July 24, 1951. Struik refused to answer any of the over 200 questions asked of him, repeatedly invoking the Fifth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. (He had planned to invoke the First, but a recent US Supreme Court case had struck down that option.) On September 12, 1951, Struik was indicted by a Middlesex County grand jury for "conspiracy to overthrow the governments of the United States and Massachusetts, and for advocating the overflow of violence by the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts" and released on $10,000 bail. Soon thereafter, the MIT faculty voted to suspend Struik with full salary until the case was resolved.[7] The indictment would be quashed in 1956 by judge Paul G. Kirk after the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled in a different case that the federal Smith Act superseded Massachusetts' sedition laws. MIT lifted Struik's suspension on May 26, 1956.[8]

In April 1953, the head of the MIT mathematics department, William Ted Martin, testified to the HUAC that he and Struik had both been members of an MIT communist cell between 1938 and 1946.[9] Struik was re-instated in 1956.[10] He retired from MIT in 1960.

Aside from purely academic work, Struik also helped found the journal Science & Society, a Marxian journal on the history, sociology and development of science. Dirk Struik and Adolph P. Yushkevich were the inaugural winners of the Kenneth O. May Prize in the History of Mathematics in 1989.[11] [12]

In 1950 Struik published his Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry,[13] which gained praise from Ian R. Porteous:

- Of all the textbooks on elementary differential geometry published in the last fifty years the most readable is one of the earliest, namely that by D.J. Struik (1950). He is the only one to mention Allvar Gullstrand.[14]

Struik's other major works include such classics as A Concise History of Mathematics (1948),[15] Yankee Science in the Making, The Birth of the Communist Manifesto, and A Source Book in Mathematics, 1200–1800, all of which are considered standard textbooks or references.

Struik died October 21, 2000, three weeks after celebrating his 106th birthday.

Books edit

- 1928: Het Probleem ‘De impletione loci’ (Dutch), Nieuw Archief voor Wiskunde, Series 2, 15 (1925–1928), no. 3, 121–137

- 1948: Yankee Science in the Making

- 1950: Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry

- 1953: Lectures on Analytic and Projective Geometry, Addison-Wesley

- 1957: The Origins of American Science (New England) via Internet Archive

- 1986: (editor) A Source Book in Mathematics, 1200–1800, Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-08404-1, ISBN 0-691-02397-2 (pbk).

- 1987: A Concise History of Mathematics, fourth revised edition, Dover Publications ISBN 0-486-60255-9, ISBN 978-0-486-60255-4.

References edit

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (October 26, 2000). "Dirk J. Struik; Historian Was 106". The New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Davis, Chandler; Tattersall, Jim; Richards, Joan; Banchoff, Tom (June–July 2001). "Dirk Jan Struik (1894-2000)" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 48 (6): 584–589. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Rowe, David E. (September 2002). "Dirk Jan Struik, 1894–2000". Isis. 93 (3): 456–459. doi:10.1086/374064. S2CID 143979122.

- ^ "Élie Cartan et Saly Ruth Ramler – Médias – MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

- ^ Struik, D. J. (1926). "Het probleem 'De Impletione Loci'". Nieuw Archief voor Wiskunde. 2nd ser. 15: 121–134. JFM 52.0002.04.

- ^ Subversive Influence in the Educational Process: Hearings Before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws to the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Eighty-second Congress, Second Session, Eighty-fourth Congress, First Session. United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952.

- ^ Simson L. Garfinkel (June 29, 2022). "How an MIT Marxist weathered the Red Scare". Technology Review.

- ^ "Struik Suspension Lifted by M. I. T.; Status Unsettled". The Boston Globe. May 27, 1956.

- ^ Simson L. Garfinkel (June 29, 2022). "How an MIT Marxist weathered the Red Scare". Technology Review.

- ^ "Deaths: Dirk J. Struik, Mathematician". The Washington Post. October 29, 2000. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Dauben, Joseph W. (1999). "Historia Mathematica: 25 Years/Context and Content". Historia Mathematica. 26 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1006/hmat.1999.2227.

- ^ "Kenneth O. May Prize in the History of Mathematics". International Mathematical Union (IMU). 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Bompiani, E. (1951). "Review: Lectures on classical differential geometry by D. J. Struik" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 57 (2): 154–155. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1951-09487-2.

- ^ Ian R. Porteous (2001) Geometric Differentiation, p 319, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-00264-8

- ^ Rowe, David E. (2001). "Looking back on a bestseller: Dirk Struik's A Concise History of Mathematics" (PDF). Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 48 (6): 590–592.

Sources edit

- Obituaries

- G. Alberts, and W. T. van Est, Dirk Jan Struik, Levensberichten en herdenkingen (Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, 2002), pp. 107–114. [1]

- MIT News Office (2000-10-25). Mathematician Professor Dirk Struik dies at 106. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, accessed 2007-07-23

External links edit

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Dirk Jan Struik", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- zbmath Dirk Jan Struik

- Dirk Jan Struik from Tufts University

- Dirk Jan Struik at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Works by or about Dirk Jan Struik at Internet Archive