Summary

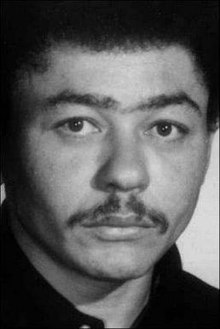

Donald Goines (pseudonym: Al C. Clark; December 15, 1936 – October 21, 1974) was an African-American writer of urban fiction.[1] His novels were deeply influenced by the work of Iceberg Slim.

Donald Goines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 15, 1936 Detroit, Michigan, US |

| Died | October 21, 1974 (aged 37) Highland Park, Michigan, US |

| Pen name | Al C. Clark |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | American |

| Literary movement | Black literature |

| Notable works | Kenyatta series (Crime Partners, Death List, Kenyatta's Escape, Kenyatta's Last Hit) Black Gangster Dopefiend Never Die Alone Whoreson |

Early life and family edit

Goines was born in Detroit, Michigan on December 15, 1936. His parents were a middle-class Black Catholic couple that ran a laundry business. His mother Myrtle Goines told Goines that her family was descended from Jefferson Davis and a woman who was enslaved.[2][3] Donald was the middle child of three, and the only son.[4]

At age 15, Goines lied about his age to join the Air Force and fought in the Korean War.[5]

Adult life edit

During his stint in the Armed Forces, Goines developed an addiction to heroin that continued after his honorable discharge in the mid-1950s. In order to support his addiction, Goines committed crimes including pimping, larceny, robbery, illegal liquor manufacturing and theft.[4] He lived in several cities, including Kansas City, Missouri and Junction City, Kansas, but mostly in his native Detroit. He was sentenced to prison several times, both state and federal.[2][4]

He began writing while serving a sentence in Michigan's Jackson Penitentiary. Goines initially attempted to write Westerns, but he decided to write urban fiction after reading Robert "Iceberg Slim" Beck's autobiography Pimp: The Story of My Life.[1][4]

Goines continued to write novels at an accelerated pace in order to support his drug addictions, with some books taking only a month to complete.[2] His sister Joan Goines Coney later said that Goines wrote at such an accelerated pace in order to avoid committing more crimes, and based many of the characters in his books on people he knew in real life.[6] He completed 16 books.[4]

In 1974 Goines published Crime Partners, the first book in the Kenyatta series under the name Al C. Clark. Holloway House's chief executive Bentley Morriss requested that Goines publish the book under a pseudonym in order to avoid having the sales of Goines's work suffer due to too many books releasing at once.[5] The book dealt with an anti-hero character named after Jomo Kenyatta that ran an organization similar to the Black Panthers to clear the ghetto of crime. In his book The Low Road, Eddie B. Allen remarks that the series was a departure from some of Goines's other works, with the character of Kenyatta symbolizing a sense of liberation for Goines.[5]

Inner City Hoodlum, which Goines had finished before his death, was published posthumously in 1975. Set in Los Angeles, the novel was about heroin, money and murder.

Death edit

On October 21, 1974 Goines and his common-law wife Shirley Sailor were discovered dead in their Highland Park, Michigan apartment. The police had received an anonymous phone call earlier that evening and responded, discovering Goines in the living room of the apartment and Sailor's body in the kitchen.[6] Both Goines and Sailor had sustained multiple gunshot wounds to the chest and head.[5]

The identity of the two gunmen[4] is unknown, as is the reason behind the murders.[5] Popular theories involve Goines being murdered due to his basing several of his characters on real life criminals as well as the theory that Goines was killed due to his being in debt over drugs.[5]

At his funeral, a relative placed a book with Goines in his casket, but it was stolen.[4]

Novels edit

Kenyatta series edit

- Crime Partners (1974) [as Al C. Clark]

- Death List (1974) [as Al C. Clark]

- Kenyatta's Escape (1974) [as Al C. Clark]

- Kenyatta's Last Hit (1975) [as Al C. Clark]

Stand alone novels edit

- Dopefiend (1971)

- Whoreson (1972)

- Black Gangster (1972)

- Street Players (1973)

- White Man's Justice, Black Man's Grief (1973)

- Black Girl Lost (1974)

- Eldorado Red (1974)

- Swamp Man (1974)

- Never Die Alone (1974)

- Cry Revenge (1974) [as Al C. Clark]

- Daddy Cool (1974)

- Inner City Hoodlum (1975)

Influence edit

Goines's writing has had an impact upon several people, with several rappers inserting mentions of Goines and his writing into their lyrics. In his 1996 song Tradin' War Stories, legendary West Coast rapper 2Pac writes "Machiavelli was my tutor, Donald Goines my father figure".[2] On the Real Brothas album by hip-hop duo B.G. Knocc Out & Dresta, the second one mentioned the author by rapping "take a good look because you're looking at a crook/my life done been took, right outta Donald Goines' book".[7]

Ludacris mentions Goines in his 2006 song "Eyebrows Down".[8]AZ compares himself to Donald Goines' work in "Rather Unique", with the line, "Your mind's boggled but I'm as deep as Donald Goines' novels". Nas also named the song "Black Girl Lost" on his sophomore album It Was Written after the book by Goines. The New York rap trio Cru had a song called "Goines Tale" where all of Donald's book titles were incorporated into the song's lyrics.

Rapper Jadakiss referenced Goines in the Sheek Louch song "Mighty D-Block (2 Guns Up)" with the lyrics "Yo, the revolve' or the mati's cool, Knife game like Daddy Cool's, since Bally Shoes". The rapper 50 Cent writes in his self-help-cum-autobiography Hustle Harder, Hustle Smarter, that "Personally, I didn’t get into reading until I found writers like Donald Goines and Iceberg Slim who wrote in a voice that felt familiar to me".

Goines' books have been utilized in several prison literacy programs. His novel Dopefiend has been taught in a Rutgers University class.[2]

Adaptations edit

Films edit

Some of Goines's works have been adapted into film. His book Crime Partners was turned into a 2001 film starring Ice-T, Snoop Dogg, and Ja Rule, and in 2004 his book Never Die Alone was also released as a film starring DMX.[9]

Graphic novel edit

In 1984 the graphic novel adaptation of the book Daddy Cool was released by Melrose Square a division of Holloway House. There have been reproductions since 1984 but it was the only graphic of its kind by Donald Goines that was published by Melrose Square.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b Liukkonen, Petri. "Donald Goines". kirjasto.sci.fi. Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 16 July 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Ogunnaike, Lola (March 25, 2004). "Credentials for Pulp Fiction: Pimp and Drug Addict; For the Novelist Donald Goines, Dead 30 Years, New Popularity and a Movie". The New York Times. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ McGraw, Bill. "Donald Goines becomes a pop-culture star half a century after his violent death". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marsh, Michael (November 14, 2012). "Raw Power". Chicago Reader. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Allen, Eddie (2003). Low Road: The Life and Legacy of Donald Goines. MacMillan. ISBN 0312383517.

- ^ a b Allen, Eddie (2004-03-24). "Detroit-sploi-tation". Metro Times. Archived from the original on 2007-08-18. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ "BG Knocc Out & Gangsta Dresta – Real Brothas". genius.com. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Eyebrows Down – Ludacris". genius.com. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (26 March 2004). "FILM REVIEW; Dying Without Remorse, A Bad Guy Who's Lonely". New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

Further reading edit

- Allen, Eddie B., Jr. Low Road: The Life and Legacy of Donald Goines. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2004.

- Nishikawa, Kinohi. "Donald Goines." Encyclopedia of Hip Hop Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2009. 102–6.

- Stone, Eddie. Donald Writes No More. Los Angeles: Holloway House, 1974.