Summary

Electrophoretic deposition (EPD), is a term for a broad range of industrial processes which includes electrocoating, cathodic electrodeposition, anodic electrodeposition, and electrophoretic coating, or electrophoretic painting. A characteristic feature of this process is that colloidal particles suspended in a liquid medium migrate under the influence of an electric field (electrophoresis) and are deposited onto an electrode. All colloidal particles that can be used to form stable suspensions and that can carry a charge can be used in electrophoretic deposition. This includes materials such as polymers, pigments, dyes, ceramics and metals.

The process is useful for applying materials to any electrically conductive surface. The materials which are being deposited are the major determining factor in the actual processing conditions and equipment which may be used.

Due to the wide utilization of electrophoretic painting processes in many industries, aqueous EPD is the most common commercially used EPD process. However, non-aqueous electrophoretic deposition applications are known. Applications of non-aqueous EPD are currently being explored for use in the fabrication of electronic components and the production of ceramic coatings. Non-aqueous processes have the advantage of avoiding the electrolysis of water and the oxygen evolution which accompanies electrolysis.

Uses edit

This process is industrially used for applying coatings to metal fabricated products. It has been widely used to coat automobile bodies and parts, tractors and heavy equipment, electrical switch gear, appliances, metal furniture, beverage containers, fasteners, and many other industrial products.

EPD processes are often applied for the fabrication of supported titanium dioxide (TiO2) photocatalysts for water purification applications, using precursor powders which can be immobilised using EPD methods onto various support materials. Thick films produced this way allow cheaper and more rapid synthesis relative to sol-gel thin-films, along with higher levels of photocatalyst surface area.

In the fabrication of solid oxide fuel cells EPD techniques are widely employed for the fabrication of porous ZrO2 anodes from powder precursors onto conductive substrates.

EPD processes have a number of advantages which have made such methods widely used[1]

- The process applies coatings which generally have a very uniform coating thickness without porosity.

- Complex fabricated objects can easily be coated, both inside cavities as well as on the outside surfaces.

- Relatively high speed of coating.

- Relatively high purity.

- Applicability to wide range of materials (metals, ceramics, polymers, )

- Easy control of the coating composition.

- The process is normally automated and requires less human labor than other coating processes.

- Highly efficient utilization of the coating materials result in lower costs relative to other processes.

- The aqueous process which is commonly used has less risk of fire relative to the solvent-borne coatings that they have replaced.

- Modern electrophoretic paint products are significantly more environmentally friendly than many other painting technologies.

Thick, complex ceramic pieces have been made in several research laboratories. Furthermore, EPD has been used to produce customized microstructures, such as functional gradients and laminates, through suspension control during processing.[2]

History edit

The first patent for the use of electrophoretic painting was awarded in 1917 to Davey and General Electric. Since the 1920s, the process has been used for the deposition of rubber latex. In the 1930s the first patents were issued which described base neutralized, water dispersible resins specifically designed for EPD.

Electrophoretic coating began to take its current shape in the late 1950s, when Dr. George E. F. Brewer and the Ford Motor Company team began working on developing the process for the coating of automobiles. The first commercial anodic automotive system began operations in 1963.

The first patent for a cathodic EPD product was issued in 1965 and assigned to BASF AG. PPG Industries, Inc. was the first to introduce commercially cathodic EPD in 1970. The first cathodic EPD use in the automotive industry was in 1975. Today, around 70% of the volume of EPD in use in the world today is the cathodic EPD type, largely due to the high usage of the technology in the automotive industry. It is probably the best system ever developed and has resulted in great extension of body life in the automotive industry

There are thousands of patents which have been issued relating to various EPD compositions, EPD processes, and articles coated with EPD. Although patents have been issued by various government patent offices, virtually all of the significant developments can be followed by reviewing the patents issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Process edit

The overall industrial process of electrophoretic deposition consists of several sub-processes:

- Preparation – this usually consists of some kind of cleaning process and may include the application of a conversion coating, typically an inorganic phosphate coating.

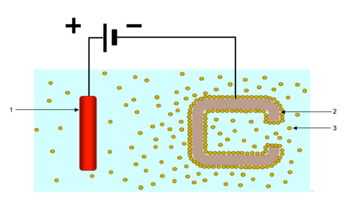

- The coating process itself – this usually involves submerging the part into a container or vessel which holds the coating bath or solution and applying direct current electricity through the EPD bath using electrodes. Typically voltages of 25 – 400 volts DC are used in electrocoating or electrophoretic painting applications. The object to be coated is one of the electrodes, and a set of "counter-electrodes" are used to complete the circuit.

- After deposition, the object is normally rinsed to remove the undeposited bath. The rinsing process may utilize an ultrafilter to dewater a portion of the bath from the coating vessel to be used as rinse material. If an ultrafilter is used, all of the rinsed off materials can be returned to the coating vessel, allowing for high utilization efficiency of the coating materials, as well as reducing the amount of waste discharged into the environment.

- A baking or curing process is normally used following the rinse. This will crosslink the polymer and allows the coating, which will be porous due to the evolution of gas during the deposition process, to flow out and become smooth and continuous.

During the EPD process itself, direct current is applied to a solution of polymers with ionizable groups or a colloidal suspension of polymers with ionizable groups which may also incorporate solid materials such as pigments and fillers. The ionizable groups incorporated into the polymer are formed by the reaction of an acid and a base to form a salt. The particular charge, positive or negative, which is imparted to the polymer depends on the chemical nature of the ionizable group. If the ionizable groups on the polymer are acids, the polymer will carry a negative charge when salted with a base. If the ionizable groups on the polymer are bases, the polymer will carry a positive charge when salted with an acid.

There are two types of EPD processes, anodic and cathodic. In the anodic process, negatively charged material is deposited on the positively charged electrode, or anode. In the cathodic process, positively charged material is deposited on the negatively charged electrode, or cathode.[3]

When an electric field is applied, all of the charged species migrate by the process of electrophoresis towards the electrode with the opposite charge. There are several mechanisms by which material can be deposited on the electrode:

- Charge destruction and the resultant decrease in solubility.

- Concentration coagulation.

- Salting out.

The primary electrochemical process which occurs during aqueous electrodeposition is the electrolysis of water. This can be shown by the following two half reactions which occur at the two electrodes:

- Anode: 2H2O → O2(gas) + 4H(+) + 4e(-)

- Cathode: 4H2O + 4e(-) → 4OH(-) + 2H2(gas)

In anodic deposition, the material being deposited will have salts of an acid as the charge bearing group. These negatively charged anions react with the positively charged hydrogen ions (protons) which are being produced at the anode by the electrolysis of water to reform the original acid. The fully protonated acid carries no charge (charge destruction) and is less soluble in water, and may precipitate out of the water onto the anode.

The analogous situation occurs in cathodic deposition except that the material being deposited will have salts of a base as the charge bearing group. If the salt of the base has been formed by protonation of the base, the protonated base will react with the hydroxyl ions being formed by electrolysis of water to yield the neutral charged base (again charge destruction) and water. The uncharged polymer is less soluble in water than it was when was charged, and precipitation onto the cathode occurs.

Onium salts, which have been used in the cathodic process, are not protonated bases and do not deposit by the mechanism of charge destruction. These type of materials can be deposited on the cathode by concentration coagulation and salting out. As the colloidal particles reach the solid object to be coated, they become squeezed together, and the water in the interstices is forced out. As the individual micelles are squeezed, they collapse to form increasingly larger micelles. Colloidal stability is inversely proportional to the size of the micelle, so as the micelles get bigger, they become less and less stable until they precipitate from solution onto the object to be coated. As more and more charged groups are concentrated into a smaller volume, this increases the ionic strength of the medium, which also assists in precipitating the materials out of solution. Both of these processes are occurring simultaneously and both contribute to the deposition of material.

Factors affecting electrophoretic painting edit

During the aqueous deposition process, gas is being formed at both electrodes. Hydrogen gas is being formed at the cathode, and oxygen gas at the anode. For a given amount of charge transfer, exactly twice as much hydrogen is generated compared to oxygen on a molecular basis.

This has some significant effects on the coating process. The most obvious is in the appearance of the deposited film prior to the baking process. The cathodic process results in considerably more gas being trapped within the film than the anodic process. Since the gas has a higher electrical resistance than either depositing film or the bath itself, the amount of gas has a significant effect on the current at a given applied voltage. This is why cathodic processes are often able to be operated at significantly higher voltages than the corresponding anodic processes.

The deposited coating has significantly higher resistance than the object which is being coated. As the deposited film precipitates, the resistance increases. The increase in resistance is proportional to the thickness of the deposited film, and thus, at a given voltage, the electric current decreases as the film gets thicker until it finally reaches a point where deposition has slowed or stopped occurring (self-limiting). Thus the applied voltage is the primary control for the amount of film applied.

The ability for the EPD coating to coat interior recesses of a part is called the "throwpower". In many applications, it is desirable to use coating materials with a high throwpower. The throwpower of a coating is dependent on a number of variables, but generally, it can be stated that the higher the coating voltage, the further a given coating will "throw" into recesses. High throwpower electrophoretic paints typically use application voltages in excess of 300 volts DC.

The coating temperature is also an important variable affecting the EPD process. The coating temperature has an effect on the bath conductivity and deposited film conductivity, which increases as temperature increases. Temperature also has an effect on the viscosity of the deposited film, which in turn affects the ability of the deposited film to release the gas bubbles being formed.

The coalescence temperature of the coating system is also an important variable for the coating designer. It can be determined by plotting the film build of a given system versus coating temperature keeping the coating time and voltage application profile constant. At temperatures below the coalescence temperature, film growth behavior and rupturing behavior is quite different from the usual practice as a result of porous deposition.

The coating time also is an important variable in determining the film thickness, the quality of the deposited film, and the throwpower. Depending on the type of object being coated, coating times of several seconds up to several minutes may be appropriate.

The maximum voltage which can be utilized depends on the type of coating system and a number of other factors. As already stated, film thickness and throwpower are dependent on the application voltage. However, at excessively high voltages, a phenomenon called "rupture" can occur. The voltage where this phenomenon occurs is called the "rupture voltage". The result of rupture is a film that is usually very thick and porous. Normally this is not an acceptable film cosmetically or functionally. The causes and mechanisms for rupturing are not completely understood, however, the following is known:

- Commercially available anodic EPD coating chemistries typically exhibit rupturing at voltages significantly lower than their commercially available cathodic counterparts.

- For a given EPD chemistry, the higher the bath conductivity, the lower the rupture voltage.

- For a given EPD chemistry, the rupture voltages normally decrease as the temperature is increased (for temperatures above the coalescence temperature).

- Additions to a given bath composition of organic solvents and plasticizers which reduce the deposited film's viscosity will often produce higher film thicknesses at a given voltage, but will generally also reduce the throwpower and the rupture voltage.

- The type and preparation of the substrate (material used to make the object being coated) can also have a significant effect on rupturing phenomenon.

Types of EPD chemistries edit

There are two major categories of EPD chemistries: anodic and cathodic. Both continue to be used commercially, although the anodic process has been in use industrially for a longer period of time and is thus considered to be the older of the two processes. There are advantages and disadvantages for both types of processes, and different experts may have different perspectives on some of the pros and cons of each.

The major advantages that are normally touted for the anodic process are:

- Lower costs compared to cathodic process.

- Simpler and less complex control requirements.

- Fewer problems with inhibition of cure of subsequent topcoating layers.

- Less sensitivity to variations in substrate quality.

- The substrate is not subjected to highly alkaline conditions, which may dissolve phosphate and other conversion coatings.

- Certain metals, such as zinc, may become embrittled from the hydrogen gas which is evolved at the cathode. The anodic process avoids this effect since oxygen is being generated at the anode.

The major advantages that are normally touted for the cathodic processes are:

- Higher levels of corrosion protection are possible. (While many people believe that cathodic technologies have higher corrosion protection capability, other experts argue that this probably has more to do with the coating polymer and crosslinking chemistry rather than on which electrode the film is deposited.)

- Higher throwpower can be designed into the product. (While this may be true with the currently commercially available technologies today, high throwpower anodic systems are known and have been used commercially in the past.)

- Oxidation only occurs at the anode, and thus staining and other problems which may result from the oxidation of the electrode substrate itself is avoided in the cathodic process.

A significant and real difference which is not often mentioned is the fact that acid catalyzed crosslinking technologies are more appropriate to the anodic process. Such crosslinkers are widely used in all types of coating applications. These include such popular and relatively inexpensive crosslinkers such as melamine-formaldehyde, phenol-formaldehyde, urea-formaldehyde, and acrylamide-formaldehyde crosslinkers.

Melamine-formaldehyde type crosslinkers in particular are widely used in anodic electrocoatings. These types crosslinkers are relatively inexpensive and provide a wide range of cure and performance characteristics which allow the coating designer to tailor the product for the desired end use. Coatings formulated with this type of crosslinker can have acceptable UV light resistance. Many of them are relatively low viscosity materials and can act as a reactive plasticizer, replacing some of the organic solvent that otherwise might be necessary. The amount of free formaldehyde, as well as formaldehyde which may be released during the baking process is of concern as these are considered to be hazardous air pollutants.

The deposited film in cathodic systems is quite alkaline, and acid catalyzed crosslinking technologies have not been preferred in cathodic products in general, although there have been some exceptions. The most common type of crosslinking chemistry in use today with cathodic products are based on urethane and urea chemistries.

The aromatic polyurethane and urea type crosslinker is one of the significant reasons why many cathodic electrocoats show high levels of protection against corrosion. Of course it is not the only reason, but if one compares electrocoating compositions with aromatic urethane crosslinkers to analogous systems containing aliphatic urethane crosslinkers, consistently systems with aromatic urethane crosslinkers perform significantly better. However, coatings containing aromatic urethane crosslinkers generally do not perform well in terms of UV light resistance. If the resulting coating contains aromatic urea crosslinks, the UV resistance will be considerably worse than if only urethane crosslinks can occur. A disadvantage of aromatic urethanes is that they can also cause yellowing of the coating itself as well as cause yellowing in subsequent topcoat layers. A significant undesired side reaction which occurs during the baking process produces aromatic polyamines. Urethane crosslinkers based on toluene diisocyanate (TDI) can be expected to produce toluene diamine as a side reaction, whereas those based on methylene diphenyl diisocyanate produce diaminodiphenylmethane and higher order aromatic polyamines. The undesired aromatic polyamines can inhibit the cure of subsequent acid catalysed topcoat layers, and can cause delamination of the subsequent topcoat layers after exposure to sunlight. Although the industry has never acknowledged this problem, many of these undesired aromatic polyamines are known or suspected carcinogens.

Besides the two major categories of anodic and cathodic, EPD products can also be described by the base polymer chemistry which is utilized. There are several polymer types that have been used commercially. Many of the earlier anodic types were based on maleinized oils of various types, tall oil and linseed oil being two of the more common. Today, epoxy and the acrylic types predominate. The description and the generally touted advantages are as follows:

- Epoxy: Although aliphatic epoxy materials have been used, the majority of EPD epoxy types are based on aromatic epoxy polymers, most commonly based on polymerization of diglycidal ethers of bis phenol A. The polymer backbone may be modified with other types of chemistries to achieve the desired performance characteristics. Generally, this type of chemistry is used in primer applications where the coating will receive a topcoat, particularly if the coated object needs to withstand sunlight. This chemistry generally does not have good resistance to UV light. However, this chemistry is often used where high corrosion resistance is required.

- Acrylic: These polymers are based on free radical initiated polymers containing monomers based on acrylic acid and methacrylic acid and their many esters which are available. Generally, this type of chemistry is utilized when UV-resistance is desirable. These polymers also have the advantage of allowing a wider color palette since the polymer is less prone to yellowing when compared to epoxies.

Kinetics edit

The rate of electrophoretic deposition (EPD) is dependent on multiple different kinetic processes acting in concert. One of the primary kinetic processes involved in EPD is electrophoresis, the movement of charged particles in response to an electric field. But as the local concentration of particles decreases near the electrodes, particle diffusion from areas of high concentration to low concentration, driven by a difference in chemical potential, will also influence the rate of deposition. This section will discuss the conditions that determine the rates of each of these processes and how those variables are incorporated into different models used to evaluate EPD.

For either process to occur the molecules must form a stable aqueous suspension. There are four common processes by which the particle can obtain surface charge needed to form a stable dispersion: 1. Dissociation or ionization of a surface group 2. Reabsorption of ions 3. Adsorption of ionized surfactants 4. Isomorphic substitution. The molecule's surface chemistry and its local environment will determine how it obtains a surface charge. Without sufficient surface charge to balance the van der Waals attractive forces between particles, they will aggregate. A charged surface is not the only parameter that influences colloidal stability. Particle size, zeta potential, and the solvent's conductivity, viscosity, and dielectric constant also determine the dispersion's stability.[4] So long as the dispersion is stable, the initial rate of deposition will be primarily determined by the electric field strength. Solution resistance can dissipate the applied voltage, so the actual surface charge on each electrode may be lower than intended. The charged particles will attach to a substrate located on the oppositely charged electrode. As a simplification, under low voltages and short deposition times, Hamaker's law[3] describes a linear relationship between the field strength, deposited thickness, and time.

This equation gives the electrophoretically deposited mass m in grams, as function of electrophoretic mobility μ (in units of cm2s−1), solids loading Cs (in g cm −3), covered surface area S (cm2), electric field strength E (V cm−1) and time t (s). This equation is useful to evaluate the efficiency of applied EPD processes relative to theoretical values.

The simple linear approximation applied by Hamaker's law degrades under higher voltages and longer deposition times. Under higher voltage, chemical reactions, such as reduction, driven by the influence of the applied field can obscure the kinetics. So, solvents with high reduction-oxidation potentials should be used to avoid electrolysis and the gas evolution.[4] And if the deposited particles are insulating, then as the deposited layer grows thicker the effective electric field will decrease. In addition, the area surrounding the electroactive region near the electrodes will be depleted of particles. Particle diffusion from the bulk to the electroactive region may limit the rate of growth. The diffusion of particles from high to low concentration can be approximated by Fick's laws and its rate will be determined by the difference in particle concentration as well as solvent viscosity, particle mass, and colloidal stability. Eventually, as deposition thickness increases and field strength decreases, the growth will saturate. The change in thickness that occurs at the onset of saturation is described by the following equation.[5]

where

w is the weight of solid particles deposited on the electrode, k the kinetic constant, t the deposition time, A the area of the electrode, V the slurry volume, the starting weight of the solid particles in the slurry, ε the dielectric constant of the liquid, ξ the zeta-potential of the particle in the solvent, n the viscosity of the solvent, E the applied direct-current voltage, and E the voltage drop across the deposited layer.[5]

Before saturation there is a linear relationship between deposition thickness and time. The onset of saturation leads to a decrease in the rate of deposition that is modelled as parabolic behavior. The critical transition time between linear and parabolic behavior is approximated by the following equation.[5]

t is the critical transition time, is the slope of the parabolic regime, and is the slope of the rate of deposition layer growth in the linear regime.

In determining the applicability of EPD to a system it is necessary to ensure the colloidal stability, and the combination of applied voltage and reaction time that will yield the intended deposited thickness.

Non-aqueous electrophoretic deposition edit

In certain applications, such as the deposition of ceramic materials, voltages above 3–4V cannot be applied in aqueous EPD if it is necessary to avoid the electrolysis of water. However, higher application voltages may be desirable in order to achieve higher coating thicknesses or to increase the rate of deposition. In such applications, organic solvents are used instead of water as the liquid medium. The organic solvents used are generally polar solvents such as alcohols and ketones. Ethanol, acetone, and methyl ethyl ketone are examples of solvents which have been reported as suitable candidates for use in electrophoretic deposition.

References edit

- ^ Gurrappa, Injeti; Binder, Leo (2008). "Electrodeposition of nanostructured coatings and their characterization—A review". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (4): 043001. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/4/043001. PMC 5099627. PMID 27878013.

- ^ Processing of ceramic materials – shaping Archived 2006-09-07 at the Wayback Machine at Catholic University of Leuven

- ^ a b Hanaor, Dorian; Michelazzi, Marco; Veronesi, Paolo; Leonelli, Cristina; Romagnoli, Marcello; Sorrell, Charles (2011). "Anodic aqueous electrophoretic deposition of titanium dioxide using carboxylic acids as dispersing agents". Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 31 (6): 1041–1047. arXiv:1303.2742. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2010.12.017. S2CID 98781292.

- ^ a b Besra, L.; Liu, M. (2007). "A review on fundamentals and applications of electrophoretic deposition (EPD)" (PDF). Progress in Materials Science. 52: 1–61. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2006.07.001.

- ^ a b c Leu, Ing-Chi (2004). "Kinetics of Electrophoretic Deposition for Nanocrystalline Zinc Oxide Coatings". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 87: 84–88. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2004.00084.x.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060907065139/http://www.mtm.kuleuven.ac.be/Research/C2/EPD.htm

- "Electrocoating"; The Electrocoat Association; Cincinnati, OH; 2002 ISBN 0-9712422-0-8

- "Finishing Systems Design and Implementation"; Society of Manufacturing Engineers; Dearborn, MI; 1993; ISBN 0-87263-434-5

- "Electrodeposition of Coatings"; American Chemical Society; Washington D.C.; 1973; ISBN 0-8412-0161-7

- "Electropainting"; R. L. Yeates; Robert Draper LTD; Teddington; 1966

- "Paint and Surface Coatings"; R. Lambourne editor; Ellis Horwood Limited; Chichester, West Sussex, England; 1987; ISBN 0-85312-692-5 and ISBN 0-470-20809-0

- www.electrocoat.org

- www.uspto.gov

- Department of Powder Technology, Saarland University, Germany