Summary

Epiphanies – or visions of gods – were reported and believed in many cities of ancient Greece. They were most commonly reported on the battlefields and, during moments of crisis, when citizens were most eager to believe that the gods of their polis were coming to assist them. An alleged visitation or manifestation of a god was known as an epiphaneia (ἡ ἐπιφάνεια). Sometimes the gods who appeared were prominent deities, but more often, they were minor figures, whose shrines were linked to the location of a particular event or battle.[1] The gods did not always reveal themselves to mortals, but could indicate their presence through physical signs or unusual phenomena.[2] They could also appear to individuals, particularly in dreams, such as the reported visit by the ‘Mother of the Gods’ to Themistokles who warned of an attempt on his life and, in return for this information, demanded that his daughter be sworn into her service.[3]

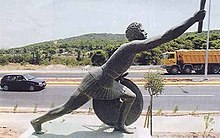

Epiphanies tend to have been reported more frequently at times of extreme danger, such as the Persian Wars. For example, at the Battle of Marathon in 490 it was said that Pan, Theseus, and another hero, fought against the Persians.[4] It was also widely believed that the runner, Pheidippides, on the eve of the battle of Marathon, met with Pan on Mount Parthenion, where the god promised to support the Athenians. After their unexpected victory, the grateful Athenians introduced Pan’s cult into their city.[5]

At the Battle of Salamis, visions of the sons of Aias were reported. Themistokles said that the Greek victory over the Persian fleet at Salamis was aided by gods and heroes.[6] It was also reported at Salamis that a supernatural cloud appeared from which could be heard the chants of initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries and it was said that a serpent representing a local hero swam in the waters assisting the Greek fleet.[7]

Accounts of attacks on Delphi, the most sacred Panhellenic sanctuary, also attracted reports of battlefield epiphanies. Herodotos says that when Xerxes’ forces attacked the sanctuary in 480, two giant heroes were seen repelling the Persians. Two hundred years later, an inscription at Delphi claimed that Apollo himself had defended his sanctuary against an attack by the Gauls.[8]

At the Battle of Aigospotamoi in 405, the Dioskouroi, were said to have taken the form of stars floating on either side of the ship of the Spartan general, Lysandros.[9] At Argos in 272 an unidentified woman was said to have thrown the tile that struck and killed King Pyrrhos. The Argives later said that this was an epiphany of Demeter.[10]

Not all epiphanies were believed. Dionysios of Halikarnassos said that many accounts of epiphanies were ridiculed.[11] There were also cases of fraudulent stories being exposed. Herodotos complained of a ruse by Peisistratos, who dressed up a tall woman, Phye, to impersonate the goddess Athena and then had her drive him in a chariot into the city so that he could win the support of the Athenians.[12] Although not all Greeks believed these stories, many did seem to accept the notion that the gods could appear in the mortal world and assist them in times of crisis.

References edit

- ^ J. McDonald, ‘Epiphanies, Military’ in I. Spence, D. Kelly and P. Londey (edd.) Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: the Definitive Political, Social and Military Encyclopedia, vol. 1 Santa Barbara, 2016, pp. 262–3.

- ^ M. P. Nilsson, A History of Greek Religion (translated by F. J. Fielden), Oxford, M. P. 1925, pp. 160–1; R. Parker, On Greek Religion, Ithaca, 2011, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Plutarch, Themistokles, 30.1–3.

- ^ Herodotos, 8.109.3; Pausanias, 1.15.4, 1.28.4, 1.32.4. See R. Parker, Athenian Religion: a History, Oxford, 1996, pp. 163–4.

- ^ Herodotos, 6.105.1–106.1; Pausanias, 1.28.4,. See R. Garland, Introducing New Gods: the Politics of Athenian Religion, Ithaca, 1992 47–63.

- ^ Herodotos, 8.64.1–2; Pausanias, 1.36.1. See R. Parker, Athenian Religion: a History, Oxford, 1996, pp. 153–5.

- ^ Herodotos, 8.65, 9.65; Plutarch, Themistokles, 15.1. See W. Burkett, Greek Religion (translated by John Raffan), Oxford, 1985. p. 207.

- ^ Herodotos 8.37–38. See V. Penazos and M. Sarla, Delphi, Athens, 1996, pp. 23–5.

- ^ D. H. Kelly, Xenophon’s Hellenika: a Commentary (ed. J. McDonald), Amsterdam, 2019, pp. 250–1, concerning Plutarch, Lysandros, 12.1.

- ^ J. McDonald, ‘Epiphanies, Military’ in I. Spence, D. Kelly and P. Londey (edd.), Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: the Definitive Political, Social and Military Encyclopedia, vol. 1 Santa Barbara, 2016, pp. 262–3.

- ^ Dionysius of Halikarnassos, 2.68.2.

- ^ Herodotos, 1.60. See J. McDonald, ‘Epiphanies, Military’ in I. Spence, D. Kelly and P. Londey (edd.) Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: the Definitive Political, Social and Military Encyclopedia, vol. 1 Santa Barbara, 2016, pp. 262–3.