Summary

Euromycter is an extinct genus of caseid synapsids that lived in what is now southern France during the Early Permian (late Artinskian) about 285 million years ago. The holotype and only known specimen of Euromycter (MNHN.F.MCL-2) includes the complete skull with lower jaws and hyoid apparatus, six cervical vertebrae with proatlas, anterior part of interclavicle, partial right clavicle, right posterior coracoid, distal head of right humerus, left and right radius, left and right ulna, and complete left manus. It was collected by D. Sigogneau-Russell and D. Russell in 1970 at the top of the M1 Member, Grès Rouge Group, near the village of Valady (département of Aveyron), Rodez Basin. It was first assigned to the species "Casea" rutena by Sigogneau-Russell and Russell in 1974. More recently, it was reassigned to its own genus, Euromycter, by Robert R. Reisz, Hillary C. Maddin, Jörg Fröbisch and Jocelyn Falconnet in 2011.[1] The preserved part of the skeleton suggests a size between 1,70 m (5,5 ft) and 1,80 m (5,9 ft) in length for this individual.[2]

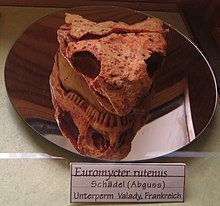

| Euromycter Temporal range: Cisuralian (late Artinskian, ~

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull cast | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | †Caseasauria |

| Family: | †Caseidae |

| Genus: | †Euromycter Reisz et al., 2011 |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Etymology edit

The generic name refers to the location of the taxon in Europe, and “mycter” = nose, refers to the enlarged external naris that characterizes the caseids.[1] The species epithet refers to ruteni (Les Rutènes in French) the Latin name of the Gallic tribe that lived in the Rodez area.[3]

Description edit

The skull is well-preserved but has suffered of a slight flattening as a result of a tectonic thrust exerted toward the right side and the front. As in other caseid, the skull is small compared to the skeleton (here mainly the forelimbs), and shows very large external nares, a short facial region, and a dorsal surface of the skull dotted of numerous small depressions. In addition, they are many palatal teeth, and the teeth of the upper jaws are numerous (four premaxillary and eleven maxillary teeth) and spatulated with crowns having 5 to 8 cusps.[3] The front teeth, fairly long and slightly recurved, were probably suited to aid in gathering vegetation into the mouth, whereas it is presumed that palatal teeth had to work in conjunction with a tough and massive muscular tongue as indicated by the presence of a very well-developed hyoid apparatus.[4][5]

Characteristically, Euromycter shows an unusually broad skull, large temporal fenestra, and lack of expansion of the axial neural spine. It can be distinguished from other caseids by the presence of a supernumerary blade-like intranarial bone located posteromedially to the septomaxilla, proportional differences in forelimb and manus, presence of an accessory proximal articulation between metacarpals 3 and 4, medial recurvature of metacarpal, and its manual phalangeal formula of 2-3-4-4-3.[3][1]

Stratigraphic range edit

The holotype of Euromycter comes from the top of the red pelitic beds of the M1 Member, in the basal part of the Grès Rouge (“Red Sandstone”) Group, a sedimentary sequence subdivided into five hectometric members (M1 to M5) localized in the western Rodez basin. The deposits are interpreted as a playa-lake environment (or Sabkha) under a semi-arid, hot climate.[1] The age of the Grès Rouge Group is uncertain but it is regarded as contemporaneous to the Saxonian Group of the neighbouring Lodève basin, where radiometric and magnetostratigraphic data suggested previously an age between the late Sakmarian (middle of the Early Permian) and the early Lopingian (early Late Permian).[6][1] However, new chronostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic data for the Saxonian Group indicate an age between the Artinskian (for the Rabejac Formation and the Octon Member of the Salagou Formation) and the late Roadian-Wordian and possibly early Capitanian (for La Lieude Formation).[7][8] A more precise stratigraphic correlation of the Permian Rodez basin with that of Lodève was proposed in 2022 by Werneburg and colleagues. In the Rodez basin, the FII Formation of the Salabru Group, underlying the Grès Rouge Group, yielded palynomorphs, conchostracans, and a tetrapod footprints assemblage equivalent to that of the Viala Formation of the Lodève basin.[9] The lower part of the Viala Formation yielded a radiometric age of 290.96 ± 0.19 Ma corresponding to the late Sakmarian.[8] It has also been determined that the M1 and M2 megasequences of the Rodez basin are equivalent to the Rabéjac Formation of the Lodève basin (and also of the Combret Member of the Saint-Pierre Formation of the Saint-Affrique basin in southern Aveyron).[9] Above the Rabéjac Formation, the lower two-thirds of the Octon Member of the Salagou Formation yielded four tuff horizons radiometrically dated. The oldest tuff horizon provided an age of 284.40 ± 0.07 Ma corresponding to the latest Artinskian.[8] Based on this dating, the Rabéjac Formation and the correlative M1 and M2 megasequences of the Grès Rouge Group can be dated to the late Artinskian.[9] A conclusion consistent with the magnetostratigraphy which suggests that the entire Grès Rouge Group (members M1 to M5) would have an age between the late Artinskian and the early Wordian.[9]

Discovery edit

During a prospecting survey carried out in the Permian red sandstones outcropping in badlands on the western flank of the Cayla Hill (commune of Valady, northwest of Rodez), the paleontologists Denise Sigogneau-Russell and Donald Eugene Russell discovered in the summer of 1970 the skeletons of two herbivorous reptiles. An eroded vertebra picked up on the western slope of the hill led the scientists to explore the surrounding canyons where they discovered a large articulated skeleton still in place in the sediments but damaged by erosion. The skull, neck, most of the limbs, and the tail had been washed away and destroyed. On the southeastern flank of the same hill, the same team discovered a bone fragment from a different animal. The systematic exploration of surrounding slopes permits the discovery of bones still in place in the rock belonging to a smaller animal than the first. The whole back of the skeleton had already destroyed by erosion. The right forearm was exposed at the surface of the rock, then was found the skull, several articulated cervical vertebrae, the left forearm articulated with the complete left manus, a piece of the right humerus and parts of the right shoulder. Both specimens were identified as caseids pelycosaurs. The smaller specimen found at about two kilometers horizontally from the first skeleton, but 120 meters lower stratigraphically, was described in 1974 and assigned to a new species of the genus Casea, Casea rutena. This animal was celebrated as the first caseid found in Western Europe, making of this species a geographical link with other specimens of the family that were previously known only in the south central United States (Texas and Oklahoma) and in the northern European Russia.[3]

In 2008, a phylogenetic analysis of Caseidae demonstrates the paraphyly of the genus Casea, the French species representing a distinct unnamed genus.[10] Three years later, the species Casea rutena was removed of the genus Casea and assigned to a new genus, Euromycter, in the new combination Euromycter rutenus. In the same article the authors described the larger and stratigraphycally younger skeleton from the Cayla Hill, and assigned it to a new genus named Ruthenosaurus.[1]

Classification edit

In the first phylogenetic analysis of the caseids published in 2008, Euromycter, then still designated as “Casea” rutena, was recovered as the sister taxon to a derive clade containing Ennatosaurus tecton, Cotylorhynchus romeri and Angelosaurus dolani.

Below the first phylogenetic analysis of Caseidae published by Maddin et al. in 2008.[10]

A phylogenetic analysis made by Benson shows a similar position for Euromycter (again regarded as “Casea” rutena).

Below the phylogenetic analysis of Caseasauria published by Benson in 2012.[11]

In 2015, Romano & Nicosia found a similar position for Euromycter in their most parsimonious analysis including nearly all caseids (to the exclusion of the very fragmentary Alierasaurus ronchi from Sardinia).

Below the most parsimonious phylogenetic analysis published by Romano & Nicosia in 2015.[12]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f Reisz, R.R.; Maddin, H.C.; Fröbisch, J.; Falconnet, J. (2011). "A new large caseid (Synapsida, Caseasauria) from the Permian of Rodez (France), including a reappraisal of "Casea" rutena Sigogneau-Russell & Russell, 1974". Geodiversitas. 33 (2): 227–246. doi:10.5252/g2011n2a2. S2CID 129458820.

- ^ Spindler F., Falconnet J. and Fröbisch J. (2016). Callibrachion and Datheosaurus, two historical and previously mistaken basal caseasaurian synapsids from Europe. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61. doi:10.4202/app.00221.2015.

- ^ a b c d e Sigoneau-Russell, D.; Russel, D.E. (1974). "Étude du premier caséidé (Reptilia, Pelycosauria) d'Europe occidentale". Bulletin du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. Série 3. 38 (230): 145–215.

- ^ Olson, E.C. (1968). "The family Caseidae". Fieldiana Geology. 17: 225–349.

- ^ Kemp, T.S. (2005). The Origin & Evolution of Mammals. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0198507611.

- ^ Lopez, M.; Gand, G.; Garric, J.; Körner, F.; Schneider, J. (2008). "The playa environments of the Lodève Permian Basin (Languedoc-France)". Journal of Iberian Geology. 34 (1): 29–56.

- ^ Evans, M.E.; Pavlov, V.; Veselovsky, R.; Fetisova, A. (2014). "Late Permian paleomagnetic results from the Lodève, Le Luc, and Bas-Argens Basins (southern France): magnetostratigraphy and geomagnetic field morphology". Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 237: 18–24. Bibcode:2014PEPI..237...18E. doi:10.1016/j.pepi.2014.09.002.

- ^ a b c Michel, L.A.; Tabor, N.J.; Montañez, I.P.; Schmitz,M.; Davydov, V.I. (2015). "Chronostratigraphy and paleoclimatology of the Lodève Basin, France: evidence for a pan-tropical aridification event across the Carboniferous-Permian boundary". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 430: 118–131. Bibcode:2015PPP...430..118M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.03.020.

- ^ a b c d Werneburg, R.; Spindler, F.; Falconnet, J.; Steyer, J.-S.; Vianey-Liaud, M.; Schneider, J.W. (2022). "A new caseid synapsid from the Permian (Guadalupian) of the Lodève basin (Occitanie, France)" (PDF). Palaeovertebrata. 45 (45(2)-e2): e2. doi:10.18563/pv.45.2.e2. S2CID 253542331.

- ^ a b Maddin, H.C.; Sidor, C.A.; Reisz, R.R. (2008). "Cranial anatomy of Ennatosaurus tecton (Synapsida: Caseidae) from the Middle Permian of Russia and the evolutionary relationships of Caseidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (1): 160–180. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[160:CAOETS]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 44064927.

- ^ Benson, R.B.J. (2012). "Interrelationships of basal synapsids: cranial and postcranial morphological partitions suggest different topologies". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (4): 601–624. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.631042. S2CID 84706899.

- ^ Romano, M.; Nicosia, U. (2015). "Cladistic analysis of Caseidae (Caseasauria, Synapsida): using the gap-weighting method to include taxa based on incomplete specimens". Palaeontology. 58 (6): 1109–1130. doi:10.1111/pala.12197. S2CID 86489484.