Summary

Evelyn Beatrice Longman (November 21, 1874 – March 10, 1954) was an American sculptor whose allegorical figure works were commissioned as monuments and memorials, adornment for public buildings, and attractions at art expositions in the early 20th-century. She became the first woman sculptor to be elected a full member of the National Academy of Design in 1919.[1]

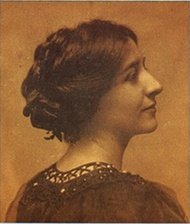

Evelyn Beatrice Longman | |

|---|---|

Longman circa 1904 | |

| Born | November 21, 1874 |

| Died | March 10, 1954 (aged 79) |

| Education | Olivet College School of the Art Institute of Chicago |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Spouse | Nathaniel Horton Batchelder (m. 1920) |

| Elected | Member of the National Academy of Design (1919) |

Early life and education edit

The daughter of Edwin Henry and Clara Delitia (Adnam) Longman, she was born on a farm near Winchester, Ohio. At the age of 14, she earned a living working in a Chicago dry-goods store.[2] At the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, which she visited when she was almost 19 years old, Longman was inspired to become a sculptor.[3] She attended Olivet College in Michigan for one year but returned to Chicago to study anatomy, drawing, and sculpture. Working under Lorado Taft at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she earned her diploma for the four-year course of study in only two years.

In 1901, Longman moved to New York, where she studied with Hermon Atkins MacNeil and Daniel Chester French. Her debut in large-scale public sculpture came at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, where her male figure, Victory, was deemed so excellent in invention and technique that it was given a place of honor on the top of the fair's centerpiece building, Festival Hall.[4] A smaller bronze version, a statuette dated 1903, was later located, and in 2007 was sold at auction for $7,800—a small price for a piece representing the hallmark of a celebrated sculptor.[5]

Career edit

Longman's 1915 Genius of Electricity, a gilded male nude, was commissioned by AT&T Corporation for the top of their corporate headquarters in downtown Manhattan. The figure was reproduced on Bell Telephone directories across the country from 1938 until the 1960s. Around 1920, Longman assisted Daniel Chester French and Henry Bacon by creating the sculptural decorations for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. In 1923, she won the Watrous Gold Medal for best sculpture.[6]

Longman is also often noted for sculpting the hands on the Lincoln Memorial, although this is not confirmed to be true. She assisted with many aspects of the Lincoln Memorial, but French himself modeled the hands.

In 1918, Longman was hired by Nathaniel Horton Batchelder, the headmaster of the Loomis Chaffee School, to sculpt a memorial to his late wife. Two years later, she married Batchelder, moving to Connecticut at the height of her career. During the next 30 years, Longman completed dozens of commissions, both architectural and independent works, throughout the United States. She was an active member of the Loomis Chaffee School, donating countless items that are currently held still at the school, as well as in the surrounding town.[7] Her work was also part of the sculpture event in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics.[8]

After her husband's retirement, Longman moved her studio to Cape Cod, where she died in 1954.

After Longman's death, her husband is rumored to have scattered her ashes at Chesterwood, the home and studio of her former employer and mentor, Daniel Chester French.

Major works edit

- Victory (1904), commissioned for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis.

- Great Bronze Memorial (1909) chapel doors at the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis.

- Allegorical sculpture for the Foster Mausoleum and bronze bas-relief for Timothy Murphy memorial, Upper Middleburgh Cemetery, Middleburgh, New York

- Horsford doors (1910), the front entrance of Clapp Library at Wellesley College.

- Wreaths, eagles and inscriptions (1914) on the inner walls of the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC.

- Aenigma, bust of German actress Kate Parsenow.[9]

- Genius of Electricity (1915), later known as Electricity and The Spirit of Communication or simply Spirit of Communication, commissioned for the top of the AT&T skyscraper in New York City, later relocated to Bedminster, NJ. It stood in the lobby AT&T's downtown Dallas, TX headquarters until 2019 when it was removed for a reimagining of the lobby to reflect the changing nature of AT&T to a media company after the acquisition of Warner Brothers, now Warner Media, a subsidiary of AT&T. It will be re-installed in the completed AT&T Discovery District in April 2020.

- Fountain of Ceres (1915) in the Court of the Four Seasons at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco.

- L'Amour (1915) in the Palace of Fine Arts at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition San Francisco.

- Senator Allison Monument (1916) Des Moines, Iowa.

- Illinois Centennial Monument (1918), Chicago, IL.

- Spirit of Victory (1926), Spanish–American War Memorial in Bushnell Park, Hartford, Connecticut.

Spirit of Victory (1926), Hartford, Connecticut. Spirit of Victory (1926), Hartford, Connecticut. This photo from 2012 shows the old patina before the monument was refinished. - Victory of Mercy (1947), Loomis Chaffee School, Windsor, CT.

Victory of Mercy (1947), Loomis Chaffee School, Windsor, Connecticut. - Edison (1952), 12.5 foot bronze portrait bust of Thomas Alva Edison in Washington D.C. at the Naval Research Laboratory.

Other works edit

Two of Longman's bas relief sculptures serve as memorials in Lowell Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts. Her 1905 sculpture of a cloaked woman holding a finger to her lips adorns the grave of John Ansley Storey.[10] Longman's Mill Girl sculpture, dedicated in 1906, memorializes Lowell mill worker Louisa Maria Wells.[11]

In 1920, Longman carved the marble fountain in the lobby of the Heckscher Museum of Art. The young grandchildren of August Heckscher posed for the three small figures that serve as its focal point. An inscription around the rim reads, "Forever wilt thou love and they be fair."

A notable sculpture on the Windsor, Connecticut town green on Broad Street is the monument dedicated "To the Patriots of Windsor." Longman sculpted the large bronze eagle with partly spread wings bearing a wreath, atop a tall fieldstone pedestal, in 1928; it was dedicated in 1929.[12] Her war shrine, Madonna and Child, is found in Windsor's Grace Episcopal Church, and was opened for community use in 1943. By the end of 1944, over 2,000 people had recorded their names on the shrine's register.[13]

Another example of her work, The Craftsman, also known as Industry can be seen outside the main entrance of A. I. Prince Technical High School in Hartford, Connecticut (formerly known as Hartford Trade School). The statue, completed in 1931, was placed there in 1960 in honor of the industrial pioneers of Hartford. Sitting on a 16,000 pound granite foundation, the approximately 1,950 pound bronze sculpture remains an inspiration to students today.[14]

Minneapolis Institute of Art collection includes Putto on a Seahorse, 1933 in bronze.[15]

Honors and awards edit

Evelyn Longman Batchelder was inducted into the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame in 1994.[1]

Noted relative edit

Longman's niece was the noted Canadian portrait and landscaper painter Mildred Valley Thornton as related on her maternal line.

Gallery edit

-

Storey Memorial (1905), Lowell Cemetery, Lowell, Massachusetts.

-

Mill Girl Monument to Louisa Maria Wells (1906), Lowell Cemetery, Lowell, Massachusetts.

-

Windsor War Memorial (1928), Windsor, Connecticut.

References edit

Notes edit

- ^ a b "Evelyn Longman Batchelder". Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. The Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ^ Proske, Beatrice Gilman, Brookgreen Gardens Sculpture, Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina, 1943 p. 137

- ^ "Evelyn Longman Batchelder". Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. The Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ^ Faude, Wilson H. (2010). Hidden History of Connecticut. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781596293199. Retrieved April 24, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Evelyn Beatrice Longman". Fine Art May 2007. Rago Arts and Auction Center. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011.

- ^ Faude, Wilson H. (2010). Hidden History of Connecticut. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9781596293199. Retrieved April 24, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Faude, Wilson H. (2010). Hidden History of Connecticut. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781596293199. Retrieved April 24, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Evelyn Batchelder". Olympedia. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Biographical Sketches of American Artists (Third ed.). Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State Library. 1915. pp. 149. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

evelyn b. longman Aenigma.

- ^ Rawson, Jr., Jonathan A. (1912). The International Studio, Volume 45. New York Offices of the International Studio. p. XCIX. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ Mihalko, Jason (June 2, 2013). "The Mill Girl (June 2, 2013)". The Irreverent Psychologist. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ Pelland, Dave. "War Memorial, Windsor". CT Monuments.net (Connecticut History in Granite and Bronze). Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- ^ Hallas, Herbert. "Windsor's War Shrine at Grace Episcopal Church". Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ Thornton, Steve. "Evelyn Beatrice Longman Commemorates the Working Class". ConnecticutHistory.org. Connecticut Humanities. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art. "Putto on Seahorse". Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

Sources edit

- Cooper, Thaddeus O. (January 13, 2004). Tour of DC. Retrieved February 9, 2005.

- Ancestry.com's Biographical Cyclopedia of U.S. Women – database online (1997). Retrieved February 9, 2005.

- Samu, Margaret. "Evelyn Beatrice Longman: Establishing a Career in Public Sculpture.” Woman’s Art Journal 25.2 (Fall 2004/Winter 2005). 8–15.

- Sandstead, Lee (2004). EvelynBeatriceLongman.org. Retrieved February 9, 2005.

- The Mercy Gallery. Retrieved February 10, 2005.

- Smithsonian American Art Museum, Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture SIRIS-Smithsonian Institution Research Information System Retrieved February 20, 2007.