Summary

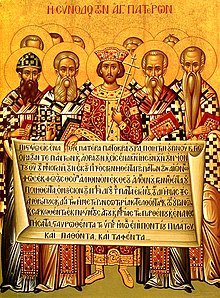

In the history of Christianity, the first seven ecumenical councils include the following: the First Council of Nicaea in 325, the First Council of Constantinople in 381, the Council of Ephesus in 431, the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, the Third Council of Constantinople from 680–681 and finally, the Second Council of Nicaea in 787. All of the seven councils were convened in what is now the country of Turkey.

These seven events represented an attempt by Church leaders to reach an orthodox consensus, restore peace[1] and develop a unified Christendom.[2] Among Eastern Christians the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Church of the East (Assyrian) churches and among Western Christians the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Utrecht and Polish National Old Catholic, and some Scandinavian Lutheran churches all trace the legitimacy of their clergy by apostolic succession back to this period and beyond, to the earlier period referred to as the Early Church.

This era begins with the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325, convened by the emperor Constantine I following his victory over Licinius and consolidation of his reign over the Roman Empire. Nicaea I enunciated the Nicene Creed that in its original form and as modified by the First Council of Constantinople of 381 was seen by all later councils as the touchstone of orthodoxy on the doctrine of the Trinity.

The Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches accept all seven of these councils as legitimate ecumenical councils. The Non-Chalcedonian Oriental Orthodox Churches accept only the first three, while the Non-Ephesian Church of the East accepts only the first two. There is also one additional council, the so-called Quinisext Council of Trullo held in AD 692 between the sixth and seventh ecumenical councils, which issued organizational, liturgical and canonical rules but did not discuss theology. Only within Eastern Orthodoxy is its authority commonly considered ecumenical; however, the Orthodox do not number it among the seven general councils, but rather count it as a continuation of the fifth and sixth. The Roman Catholic Church does not accept the Quinisext Council,[3][4] but both the Roman magisterium as well as a minority of Eastern Orthodox hierarchs and theological writers consider there to have been further ecumenical councils after the first seven. (see the Fourth Council of Constantinople, Fifth Council of Constantinople, and fourteen additional post-schism ecumenical councils canonical for Catholics).

The councils edit

These seven ecumenical councils are:

| Council | Date | Convoked by | President | Attendance (approx.) | Topics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Council of Nicaea | 20 May-19 June 325 | Emperor Constantine I | Hosius of Corduba (and Emperor Constantine) | 318 | Arianism, the nature of Christ, celebration of Passover (Easter), ordination of eunuchs, prohibition of kneeling on Sundays and from Easter to Pentecost, validity of baptism by heretics, lapsed Christians, sundry other matters. |

| First Council of Constantinople | May–July 381 | Emperor Theodosius I | Timothy of Alexandria, Meletius of Antioch, Gregory Nazianzus, and Nectarius of Constantinople | 150 | Arianism, Apollinarism, Sabellianism, Holy Spirit, successor to Meletius |

| Council of Ephesus | 22 June-31 July 431 | Emperor Theodosius II | Cyril of Alexandria | 200–250 | Nestorianism, Theotokos, Pelagianism |

| Council of Chalcedon | 8 October-1 November 451 | Emperor Marcian | Papal Legates of Pope Leo I: Paschasinus of Lilybaeum, Lucentius of Asculanum, Julian of Cos, and the presbyter Boniface. (Formal presidency)[5] | 520 | The judgments issued at the Second Council of Ephesus in 449, the alleged offences of Bishop Dioscorus of Alexandria, the relationship between the divinity and humanity of Christ, many disputes involving particular bishops and sees. |

| Second Council of Constantinople | 5 May-2 June 553 | Emperor Justinian I | Eutychius of Constantinople | 152 | Nestorianism, Monophysitism, Origenism |

| Third Council of Constantinople | 7 November 680-16 September 681 | Emperor Constantine IV | Patriarch George I of Constantinople | 300 | Monothelitism, the human and divine wills of Jesus |

| Second Council of Nicaea | 24 September-23 October 787 | Constantine VI and Empress Irene (as regent) | Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople, legates of Pope Adrian I | 350 | Iconoclasm |

First Council of Nicaea (325) edit

Emperor Constantine convened this council to settle a controversial issue, the relation between Jesus Christ and God the Father. The Emperor wanted to establish universal agreement on it. Representatives came from across the Empire, subsidized by the Emperor. Previous to this council, the bishops would hold local councils, such as the Council of Jerusalem, but there had been no universal, or ecumenical, council.

The council drew up a creed, the original Nicene Creed, which received nearly unanimous support. The council's description of "God's only-begotten Son", Jesus Christ, as of the same substance with God the Father became a touchstone of Christian Trinitarianism. The council also addressed the issue of dating Easter (see Quartodecimanism and Easter controversy), recognised the right of the See of Alexandria to jurisdiction outside of its own province (by analogy with the jurisdiction exercised by Rome) and the prerogatives of the churches in Antioch and the other provinces[6] and approved the custom by which Jerusalem was honoured, but without the metropolitan dignity.[7]

The Council was opposed by the Arians, and Constantine tried to reconcile Arius, after whom Arianism is named, with the Church. Even when Arius died in 336, one year before the death of Constantine, the controversy continued, with various separate groups espousing Arian sympathies in one way or another.[8] In 359, a double council of Eastern and Western bishops affirmed a formula stating that the Father and the Son were similar in accord with the scriptures, the crowning victory for Arianism.[8] The opponents of Arianism rallied, and the First Council of Constantinople in 381 marked the final victory of Nicene orthodoxy within the Empire, though Arianism had by then spread to the Germanic tribes, among whom it gradually disappeared after the conversion of the Franks to Christianity in 496.[8]

Constantine commissions Bibles edit

In 331, Constantine I commissioned Eusebius to deliver fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius (Apol. Const. 4) recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists, and that Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus are examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta and Codex Alexandrinus, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.[9]

First Council of Constantinople (381) edit

The council approved the current form of the Nicene Creed used in most Oriental Orthodox churches. The Eastern Orthodox Church uses the council's text but with the verbs expressing belief in the singular: Πιστεύω (I believe) instead of Πιστεύομεν (We believe). The Catholic Church's Latin Church and its liturgies also use the singular and, except in Greek,[10] adds two phrases, Deum de Deo (God from God) and Filioque (and the Son). The form used by the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, has many more additions.[11] This fuller creed may have existed before the Council and probably originated from the baptismal creed of Constantinople.[12]

The council also condemned Apollinarism,[13] the teaching that there was no human mind or soul in Christ.[14] It also granted Constantinople honorary precedence over all churches save Rome.[13]

The council did not include Western bishops or Roman legates, but it was later accepted as ecumenical in the West.[13]

First Council of Ephesus (431) edit

Theodosius II called the council to settle the christological controversy surrounding Nestorianism. Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, opposed use of the term Theotokos (Greek: Ἡ Θεοτόκος, "God-Bearer").[15] This term had long been used by orthodox writers, and it was gaining popularity along with devotion to Mary as Mother of God.[15] He reportedly taught that there were two separate persons in the incarnate Christ, though whether he actually taught this is disputed.[15]

The council deposed Nestorius, repudiated Nestorianism, and proclaimed the Virgin Mary as the Theotokos.

After quoting the Nicene Creed in its original form, as at the First Council of Nicaea, without the alterations and additions made at the First Council of Constantinople, it declared it "unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν) Faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicæa."[16]

Council of Chalcedon (451) edit

The council repudiated the Eutychian doctrine of monophysitism, described and delineated the "Hypostatic Union" and two natures of Christ, human and divine; adopted the Chalcedonian Definition. For those who accept it (Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholics, and most Protestants), it is the Fourth Ecumenical Council (calling the Second Council of Ephesus, which was rejected by this council, the "Robber Synod" or "Robber Council").

Before the council edit

In November 448, a synod at Constantinople condemned Eutyches for unorthodoxy.[17] Eutyches, archimandrite (abbot) of a large Constantinopolitan monastery,[18] taught that Christ was not consubstantial with humanity.[19]

In 449, Theodosius II summoned a council at Ephesus, where Eutyches was exonerated and returned to his monastery.[17] This council was later overturned by the Council of Chalcedon and labeled "Latrocinium" (i.e., "Robber Council").[17]

Second Council of Constantinople (553) edit

This council condemned certain writings and authors which defended the christology of Nestorius. This move was instigated by Emperor Justinian in an effort to conciliate the monophysite Christians, it was opposed in the West, and the Popes' acceptance of the council caused a major schism.[20]

Three Chapters edit

Prior to the Second Council of Constantinople was a prolonged controversy over the treatment of three subjects, all considered sympathetic to Nestorianism, the heresy that there are two separate persons in the Incarnation of Christ.[21] Emperor Justinian condemned the Three Chapters, hoping to appeal to miaphysite Christians with his anti-Nestorian zeal.[22] Monophysites believe that in the Incarnate Christ there is only one nature (i.e. the divine) not two[19] while miaphysites believe that the two natures of Christ are united as one and are distinct in thought only.

Eastern Patriarchs supported the Emperor, but in the West his interference was resented, and Pope Vigilius resisted his edict on the grounds that it opposed the Chalcedonian decrees. [22] Justinian's policy was in fact an attack on Antiochene theology and the decisions of Chalcedon.[22] The pope assented and condemned the Three Chapters, but protests in the West caused him to retract his condemnation.[22] The emperor called the Second Council of Constantinople to resolve the controversy.[22]

Council proceedings edit

The council, attended mostly by Eastern bishops, condemned the Three Chapters and, indirectly, the Pope Vigilius.[22] It also affirmed Constantinople's intention to remain in communion with Rome.[22]

After the council edit

Vigilius declared his submission to the council, as did his successor, Pope Pelagius I.[22] The council was not immediately recognized as ecumenical in the West, and Milan and Aquileia even broke off communion with Rome over this issue.[20] The schism was not repaired until the late 6th century for Milan and the late 7th century for Aquileia.[20]

Emperor Justinian's policy failed to reconcile the Monophysites.[22]

Third Council of Constantinople (680–681) edit

Third Council of Constantinople (680–681): repudiated monothelitism, a doctrine that won widespread support when formulated in 638; the Council affirmed that Christ had both human and divine wills.

Quinisext Council edit

Quinisext Council (= Fifth-Sixth Council) or Council in Trullo (692) has not been accepted by the Roman Catholic Church. Since it was mostly an administrative council for raising some local canons to ecumenical status, establishing principles of clerical discipline, addressing the Biblical canon, without determining matters of doctrine, the Eastern Orthodox Church does not consider it to be a full-fledged council in its own right, viewing it instead as an extension of the fifth and sixth councils. It gave ecclesiastical sanction to the Pentarchy as the government of the state church of the Roman Empire.[23]

Second Council of Nicaea (787) edit

Second Council of Nicaea (787). In 753, Emperor Constantine V convened the Synod of Hieria, which declared that images of Jesus misrepresented him and that images of Mary and the saints were idols.[24] The Second Council of Nicaea restored the veneration of icons and ended the first iconoclasm.

Subsequent events edit

In the 9th century, Emperor Michael III deposed Patriarch Ignatius of Constantinople and Photius was appointed in his place. Pope Nicholas I declared the deposition of Ignatius invalid. After Michael was murdered, Ignatius was reinstated as patriarch without challenge and in 869–870 a council in Constantinople, considered ecumenical in the West, anathematized Photius. With Ignatius' death in 877, Photius became patriarch, and in 879–880 another council in Constantinople, which many Easterners consider ecumenical, annulled the decision of the previous council.[25]

See also edit

- Ancient church councils (pre-ecumenical) – church councils before the First Council of Nicaea

- Byzantine Empire

- Late ancient history of Christianity

- Outline of the Catholic ecumenical councils

- Synod of Ancyra

- Synodicon Orientale

- Timeline of Christianity

References edit

- ^ "They renounced their false opinions and died in peace with the Church." (Russian: "отказались от своих ложных мнений и скончались в мире с Церковью.") Slobodskoy, Serafim Alexivich (1992). "Short Summaries of the Ecumenical Councils". The Law of God. Translated by Price, Susan. Holy Trinity Monastery (Jordanville, New York). ISBN 978-0-88465-044-7. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) Original: Слободской, Серафим Алексеевич (1957). "Краткие сведения о вселенских соборах" [Short Summaries of the Ecumenical Councils]. Закон Божий [The Law of God] (in Russian) (published 1966). Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2019.{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^

Diehl, Charles (1923). "1: Leo III and the Isaurian Dynasty (717-802)". In Tanner, J. R.; Previté-Orton, C. W.; Brooke, Z. N. (eds.). The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. IV: The Eastern Roman Empire (717-1453). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9785872870395. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

... Tarasius ... skilfully put forward the project of an Ecumenical Council which should restore peace and unity to the Christian world. The Empress [...] summoned the prelates of Christendom to Constantinople for the spring of 786. ... Finally the Council was convoked at Nicaea in Bithynia; it was opened in the presence of the papal legates on 24 September 787. This was the seventh Ecumenical Council.

- ^ Schaff's Seven Ecumenical Councils: Introductory Note to Council of Trullo: "From the fact that the canons of the Council in Trullo are included in this volume of the Decrees and Canons of the Seven Ecumenical Councils it must not for an instant be supposed that it is intended thereby to affirm that these canons have any ecumenical authority, or that the council by which they were adopted can lay any claim to being ecumenical either in view of its constitution or of the subsequent treatment by the Church of its enactments."

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica "Quinisext Council". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 14, 2010. "The Western Church and the Pope were not represented at the council. Justinian, however, wanted the Pope as well as the Eastern bishops to sign the canons. Pope Sergius I (687–701) refused to sign, and the canons were never fully accepted by the Western Church".

- ^ Price, Richard; Gaddis, Michael (2007). The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon. Vol. 45. Liverpool University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-84631-100-0. Archived from the original on 2023-12-25.

- ^ canon 6 Archived September 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ canon 7 Archived September 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Arianism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ The Canon Debate, McDonald and Sanders editors, 2002, pages 414-415, for the entire paragraph

- ^ See official Greek translation of the Roman Missal and the document The Greek and Latin Traditions about the Procession of the Holy Spirit by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, which states: "The Catholic Church has refused the addition καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ to the formula τὸ ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς ἐκπορευόμενον in the Greek text of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Symbol, even in its liturgical use by Latins"

- ^ Armenian Church Library: Nicene Creed

- ^ "Nicene Creed." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b c "Constantinople, First Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Apollinarius." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b c "Nestorius." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Council of Ephesus (A.D. 431)".

- ^ a b c "Latrocinium." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Eutyches" and "Archimandrite." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b "Monophysitism." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b c "Constantinople, Second Council of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Nestorianism" and "Three Chapters." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Three Chapters." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Pentarchy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 14, 2010. "Pentarchy. The proposed government of universal Christendom by five patriarchal sees under the auspices of a single universal empire. Formulated in the legislation of the emperor Justinian I (527–65), especially in his Novella 131, the theory received formal ecclesiastical sanction at the Council in Trullo (692), which ranked the five sees as Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem".

- ^ "Iconoclastic Controversy." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Photius", in Cross, F. L., ed., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (New York: Oxford University Press. 2005)

External links edit

- Schaff's The Seven Ecumenical Councils

- Fourth-Century Christianity