Summary

The French occupation zone in Germany (German: Französische Besatzungszone, French: Zone d'occupation française en Allemagne) was one of the Allied-occupied areas in Germany after World War II.

| French occupation zone in Germany Französische Besatzungszone Deutschlands | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Military occupation zone of the French part of Allied-occupied Germany | |||||||||||||

| 1945–1949 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

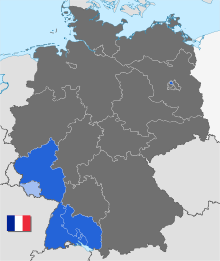

French occupation zone, in blue | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Baden-Baden | ||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||

| • Type | Military Occupation (member of Western Bloc) | ||||||||||||

| Military governors | |||||||||||||

• 1945 | Jean de Lattre de Tassigny | ||||||||||||

• 1945–1949 | Marie-Pierre Kœnig | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-World War II Cold War | ||||||||||||

| 8 May 1945 | |||||||||||||

• Federal Republic of Germany established | 23 May 1949 | ||||||||||||

| 5 May 1955 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||||||||

Background edit

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin met at the Yalta Conference to discuss Germany's post-war occupation, which included among other things coming to a final determination of the inter-zonal borders.

Originally, there were to be only three zones, with the French excluded. French General Charles de Gaulle, who by this point was the leader of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, was not invited to Yalta. Deeply offended by this snub, the French leader nevertheless worked tirelessly to restore his nation's honour in the aftermath of the German occupation. Key to this was ensuring a French occupation of substantial German territories – in de Gaulle's view, only a French occupation of Germany could restore the honour of France. He therefore vehemently demanded that a zone be allocated for French occupation.[1]

Despite the personal disdain each of the "Big Three" held for de Gaulle, they were not overly inclined to resist this particular demand. With relatively minor exceptions such as the Channel Islands, the Western Allies' own territories had not been invaded or occupied and thus they did not have the sort of considerations the French deeply felt with respect to matters such as national honour or pride. More importantly perhaps, as a civil and military matter a French occupation zone would relieve the other Allies of some of the burden of administering German territory – this was no small consideration especially in light of the fact the British and Americans still had the Japanese Empire to subdue after Germany's defeat. Stalin, who was still neutral in the Far Eastern conflict at this point, also agreed. However, the Soviet leader insisted on the condition that the French zone was to be formed out of the previously-agreed American and British zones.

French zone edit

For obvious practical and logistical reasons, it was soon agreed that the French would occupy those regions of Germany bordering their own country, i.e. southwestern Germany. To create the occupation zone, the British ceded the Saarland, the Palatinate, and territories on the left bank of the Rhine to Remagen (including Trier, Koblenz, and Montabaur). The Americans ceded land south of Baden-Baden, land south of the Free People's State of Württemberg (which became Württemberg-Hohenzollern), the Lindau region on Lake Constance, and four regions in Hesse east of the Rhine.[1] French Forces in Germany took possession of the area on 26 July 1945.[1]

Also included in the French zone was the town of Büsingen am Hochrhein, a German exclave separated from the rest of the country by a narrow strip of neutral Swiss territory. The Swiss government refused to consider annexing the town on the grounds that any transfer of territory could only be negotiated with a sovereign German government - something which had ceased to exist following the German surrender. However, the Swiss shared French concerns that the exclave might become a haven for Nazi war criminals, thus an agreement was quickly reached to allow limited numbers of French soldiers to cross Switzerland for the purpose of maintaining law and order in Büsingen.

In April and May, the French 1st Army had captured Karlsruhe and Stuttgart and conquered territory extending to Hitler's Eagle's Nest and western Austria. In July, the French ceded Stuttgart to the Americans in exchange for control of cities west of the Rhine (including Mainz and Koblenz).[2] This resulted in two barely-contiguous areas of Germany along the French border, which met at a point along the Rhine. After further negotiations, France was also granted an occupation zone in Austria. The French zone in west of that country bordered the French zone in Germany, thus creating a contiguous area of French-occupied territories (besides the aforementioned exclave of Büsingen am Hochrhein) that bordered each other and/or France itself.

Within French-occupied Germany, three German states were established: Rheinland Pfalz in the northwest, Württemberg-Hohenzollern in the southeast, and South Baden in the southwest. Württemberg-Hohenzollern and South Baden later formed Baden-Württemberg when they joined with Württemberg-Baden in the American Zone. The French occupation zone initially included the Saar Protectorate, but this was separated on 16 February 1946. By 18 December that year, customs controls were established between the Saar area and Allied-occupied Germany.

On 9 February 1945 the Berlin districts of Reinickendorf and Wedding were assigned to the French.[3][failed verification] By the end of October 1946, the French zone had a population of approximately five million:

- Rheinland Pfalz: 2.7 million

- Baden (South Baden): 1.2 million

- Württemberg-Hohenzollern: 1.05 million

The Saar Protectorate had an additional 0.8 million people.[4] The French Education Directorate in Germany was created to educate the children of military and civilian families.

On 18 May 1947 the first Landtag elections were held in the French zone. In Rhineland-Palatinate, Peter Altmeier (CDU) formed an all-parties government with CDU, SPD, FDP and KPD; in Baden, CDU won a majority, but Leo Wohleb (CDU) at first formed at first a grand coalition with SPD, but in 1948 decided to govern alone without a coalition and in Württemberg-Hohenzollern, Lorenz Bock (CDU) formed a "Germany coalition" with CDU, SPD and FDP.

Zone commanders edit

After representing the French during the signing of the German Instrument of Surrender, which officially ended the conflict in the European theater, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny briefly served as commander-in-chief of the French Forces in Germany[5] before the role was assumed by Marie-Pierre Kœnig.[6] André François-Poncet, ambassador to Germany during the 1930s, was named French high commissioner to West Germany after the war. François-Poncet's position was later elevated to ambassador, and he served in that capacity until 1955.[7][8] Claude Hettier de Boislambert, Guillaume Widmer and Pierre Pène were governors of the Rhineland-Palatinate, Württemberg-Hohenzollern and Baden, respectively.[9]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c H. Pennein-Engels (1994). "The military presence in Germany from 1945 to 1993" (PDF). University of Metz – Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ de Gaulle, Charles (1959). Mémoires de Guerre: Le Salut 1944–1946. Plon. pp. 170, 207.

- ^ "French Military Government of Berlin" (PDF). Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "I. Gebiet und Bevölkerung". Statistisches Bundesamt. Wiesbaden.

- ^ H. Pennein-Engels (1994). "The military presence in Germany from 1945 to 1993" (PDF). University of Metz – Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences. p. 29. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Reinisch, J. (2013). "Chapter 8: The Forgotten Zone: Public Health Work in the French Occupation Zone". The Perils of Peace: The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany. Oxford (UK): OUP Oxford.

- ^ Richard Gilmore (1973). France's Postwar Cultural Policies and Activities in Germany. Balmar Reprographics. p. 41.

- ^ Creswell, Michael; Trachtenberg, Marc. "France and the German Question, 1945–1955" (PDF). p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2004. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Karin Graf (2003). Die Bodenreform in Württemberg-Hohenzollern nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Tectum Verlag DE. p. 19.

Further reading edit

- Corine Defrance, La Politique culturelle de la France sur la rive gauche du Rhin, 1945–1955, Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 1994.

- Compte rendu du deuxième Congrès de l'Organisation des fonctionnaires résistants en Allemagne, Höllhof, 1949

- Hillel, Marc, L'occupation française en Allemagne 1945–1949, Balland, 1983.