Summary

Frieda is a 1947 British drama film directed by Basil Dearden and starring David Farrar, Glynis Johns and Mai Zetterling.[2] Made by Michael Balcon at Ealing Studios, it is based on the 1946 play of the same title by Ronald Millar who co-wrote the screenplay with Angus MacPhail. The film's sets were designed by the art directors Jim Morahan and Michael Relph.

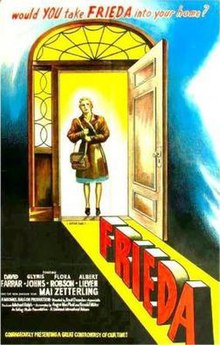

| Frieda | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Basil Dearden |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Frieda by Ronald Millar |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gordon Dines |

| Edited by | Leslie Norman |

| Music by | John Greenwood |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | General Film Distributors |

Release date | 19 June 1947 |

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £168,435[1] |

| Box office | £227,017[1] |

During World War II, a German woman rescues an English prisoner-of-war. He decides to marry her, though he does not actually love her. Following the war, the couple settle in Oxfordshire. Frieda has to deal with both anti-German sentiment in post-war Britain, and with her unrepentant Nazi brother.

Plot edit

Frieda is a German woman who helps English airman Robert to escape from a German prisoner-of-war camp as the Second World War nears its end. She loves him; he is only grateful to her. In a church between the Russian-German lines, however, Robert marries her, so that she can obtain a British passport. Together they eventually arrive in his Oxfordshire home. Frieda meets his family: his mother, his small stepbrother Tony, Judy, the attractive widow of Robert's brother, and Aunt Eleanor, a figure in local politics and vehemently anti-German.

At first, the townspeople are bitterly hostile to Frieda, and Robert is forced to give up his job as a schoolteacher. Gradually, however, the ill will subsides, and she is accepted, except by Eleanor. Frieda is befriended by Judy, who, unknown to Robert, is now also in love with him. As Robert settles into a new life, working with Frieda on a farm, he begins to lose his prisoner-of-war heaviness. He sees Frieda in a new light. But then they see a film dealing with the horror of Bergen-Belsen and Frieda fears their marriage will not survive its revelation of her countrymen's cruelty. But Robert clings on to what they have established between them.

Suddenly, an ex-German soldier appears—Frieda's brother Richard. Thinking he had been killed, Frieda is initially overjoyed. He had been captured and allowed to volunteer for the Polish Army. However, she soon realises that he has remained a Nazi at heart, his wedding present to Frieda being a swastika on a chain. In a pub, he is denounced as one of the guards at a concentration camp. To Robert, in private, he admits the truth of this accusation, and claims that Frieda had known and approved of his actions. They fight, and Robert now revolts against everything German as vile and polluted.

Frieda, fearing that she has lost Robert, attempts suicide, but, just in time, Robert reaches her and the shock brings him to a realisation of what he risked losing. He perceives that his faith in her was justified. Even Aunt Eleanor comes to believe that her sweeping anti-German prejudice was wrong: "You cannot treat human beings as though they were less than human—without becoming less than human yourself."[3]

Cast edit

- David Farrar as Robert

- Glynis Johns as Judy

- Mai Zetterling as Frieda

- Flora Robson as Nell

- Albert Lieven as Richard

- Barbara Everest as Mrs Dawson

- Gladys Henson as Edith

- Ray Jackson as Tony

- Patrick Holt as Alan

- Milton Rosmer as Merrick

- Barry Letts as Jim Merrick

- Gilbert Davis as Lawrence

- Renee Gadd as Mrs. Freeman

- Douglas Jefferies as Hobson

- Barry Jones as Holliday

- Eliot Makeham as Bailey

- Norman Pierce as Crawley

- John Ruddock as Granger

- D. A. Clarke-Smith as Herriot

- Garry Marsh as Beckwith

- Aubrey Mallalieu as Irvine

- John Molecey as Latham

- Stanley Escane as Post-boy

- Gerard Heinz as Polish Priest

- Arthur Howard as First Official

Reception edit

Box office edit

The film was the ninth most popular film at the British box office in 1947.[4][5] According to Kinematograph Weekly the 'biggest winner' at the box office in 1947 Britain was The Courtneys of Curzon Street, with "runners up" being The Jolson Story, Great Expectations, Odd Man Out, Frieda, Holiday Camp and Duel in the Sun.[6] The film earned distributor's gross receipts of £227,017 in the UK of which £184,055 went to the producer.[1]

The film was released in 1948 in the United States to excellent box office results.[7]

References edit

- ^ a b c Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 355. Gross is distributor's gross receipts.

- ^ "Frieda (1947)". Archived from the original on 13 January 2009.

- ^ Daily Mail Film Award Annual 1948

- ^ James Mason 1947 Film Favourite The Irish Times 2 January 1948: 7.

- ^ Thumim, Janet. "The popular cash and culture in the postwar British cinema industry". Screen. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 258.

- ^ Lant, Antonia (1991). Blackout : reinventing women for wartime British cinema. Princeton University Press. p. 232.

- ^ "Variety (May 1948)". Variety. New York, NY: Variety Publishing Company. May 1948.

External links edit

- Frieda at IMDb

- Frieda at AllMovie

- Frieda at BFI Screenonline

- Review of film at Variety