Summary

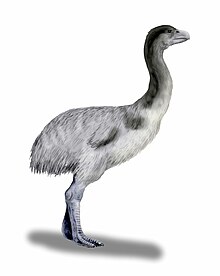

Genyornis newtoni, also known as the Newton's mihirung, Newton's thunder bird or mihirung paringmal (meaning "giant bird" in Tjapwuring), is an extinct species of large, flightless bird that lived in Australia during the Pleistocene Epoch until around 50,000 years ago. Over two metres in height, they were likely herbivorous.[2] Many other species of Australian megafauna became extinct in Australia around that time, coinciding with the arrival of humans. It is the last known member of the extinct flightless bird family Dromornithidae which had been part of the fauna of the Australian continent for over 30 million years. They are not closely related to ratites such as emus, and their closest living relatives are thought to be fowl.

| Genyornis Temporal range: Late Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | incertae sedis |

| Order: | †Gastornithiformes |

| Family: | †Dromornithidae |

| Genus: | †Genyornis |

| Species: | †G. newtoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Genyornis newtoni | |

Taxonomy edit

The species was first described in 1896 by Edward Charles Stirling and A. H. C. Zeitz, the authors giving the epithet newtoni for the Cambridge professor Alfred Newton. The name of the genus is derived from the ancient Greek γένυς (génus) 'jaw; chin' and ὄρνις (órnis) 'bird', because of the relatively large size of the lower mandible.[1] The type specimen is a left femur.[1][3] The type locality is Lake Callabonna in South Australia. The excavation was undertaken and described by Zietz. A description of the excavation was reported in Nature[4][5] which had also unearthed material recognised as marsupials. Numerous fragments of avian fossils were noticed in the clay surrounding the removal of diprotodont fossils, then largely complete specimens including crucial evidence of the crania emerged from the site. The paper reviewed previously described fossil remains of "struthious [ostrich-like] birds in Australia", which had either been assigned to the ancient emus of Dromaius or the only described species of Dromornis, D. australis Owen.[1]

A letter from George Hurst concerning the discovery of a partial skeleton of the species alerted Stirling to its existence in 1893.[3]

The placement of this dromornithid species may be summarised as:

Dromornithidae (8 species in 4 genera)[2]

- Dromornis

- Barawertornis

- Ilbandornis P. Rich, 1979

- Genyornis

- Genyornis newtoni Stirling & A. H. C. Zietz, 1896

Description edit

Genyornis newtoni was a medium-sized dromornithid with a robust body. While larger than Ilbandornis, it did not attain the height and weight of Dromornis stirtoni or Dromornis planei. The fossils of the species have been found remaining in articulation; no other dromornithid species has been discovered in this state. The remains of eggs have also been attributed to this species. Gastroliths belonging to these animals have been found alongside their remains, a feature that has revealed the sometimes shallow site of fossils.[3]

Distribution edit

This mihirung has been found at sites in South Australia, New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia, dating to the Pleistocene Epoch. Genyornis newtoni is the only species of dromornithid known to have existed during the Pleistocene.[3]

Extinction edit

Two main theories propose a cause for megafauna extinction - human impact and changing climate. A study has been performed in which more than 700 Genyornis eggshell fragments were dated.[6] Through this, it was determined that Genyornis declined and became extinct over a short period—too short for it to be plausibly explained by climate variability. The authors considered this to be a very good indication that the entire mass extinction event in Australia was due to human activity, rather than climate change.

A 2015 study collected egg shell fragments of Genyornis from around 200 sites that show burn marks.[7] Analysis of amino acids in the egg shells showed a thermal gradient consistent with the egg being placed on an ember fire. The egg shells were dated to between 53.9 and 43.4 thousand years BP, suggesting that humans were collecting and cooking Genyornis eggs in the thousands of years before their extinction. A later study, however, suggested that the eggs actually belonged to the giant malleefowl, a species of extinct megapode.[8][9] A 2022 study examined the protein sequences of these unidentified eggshells and, through phylogenetic analysis, concluded that the lineage that produced these eggs diverged prior to the emergence of megapodes, supporting the previous implication that the eggs in question were produced by Genyornis.[10] The authors also noted that the exploitation of Genyornis eggs appears to mirror that of earlier human usage of ostrich eggs throughout the Pleistocene in Northern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Southwestern and Northern Asia, and present-day India and China, though they were unable to determine to what extent humans interacted with Genyornis.[11] A 2021 study found that, if Genyornis eggs were being consumed at similar rates to the eggs of the emu and the Australian brushturkey, then Genyornis would have become extinct at far lower rates of total consumption than these still-extant birds.[12]

In May 2010, archaeologists announced the rediscovery of an Aboriginal rock art painting, possibly 40,000 years old, at the Nawarla Gabarnmung rock art site in the Northern Territory, that they suggested depicts two Genyornis individuals.[13] Late survival of Genyornis in temperate south west Victoria has also recently been suggested, based on Aboriginal traditions.[14] However, a later study suggested that the painting could not be more than 14,000 years old, long after the bird is thought to have gone extinct,[15][16] and it could not be morphologically distinguished from depictions of other birds.[17]

Fossil evidence suggests that the population of Genyornis at Lake Callabonna died around 50,000 years ago as the lake dried up as the climate changed and became drier. The birds recovered from the site also seemed to have been particularly prone to osteomyelitis as a result of getting stuck in the mud of the drying lake bed as the water receded. Eventually, when the lake dried, the population was left without their main source of water and subsequently died out.[18]

References edit

- ^ a b c d Stirling, E. C.; Zeitz, A. H. C. (1896). "Preliminary Notes on Genyornis newtoni; A New Genus and Species of Fossil Struthious Bird found at Lake Callabonna South Australia". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 20. The Society: 171–175. Read August 4, 1896.

- ^ a b Handley, Warren D.; Worthy, Trevor H. (15 March 2021). "Endocranial Anatomy of the Giant Extinct Australian Mihirung Birds (Aves, Dromornithidae)". Diversity. 13 (3): 124. doi:10.3390/d13030124.

- ^ a b c d Murray, Peter; Vickers-Rich, Patricia (2004). Magnificent mihirungs : the colossal flightless birds of the Australian dreamtime. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-253-34282-9.

- ^ Stirling, E. C. (1894). "The recent discovery of fossil remains at Lake Calabonna, South Australia. [part b]". Nature. 50. Macmillan Journals Ltd., etc.: 206–211.

- ^ Stirling, E. C. (1894). "The recent discovery of fossil remains at Lake Calabonna, South Australia. [part a]". Nature. 50. Macmillan Journals Ltd., etc.: 184–188.

- ^ Miller, G. H.; Magee, J. W.; Johnson, B. J.; Fogel, M. L.; Spooner, N. A.; McCulloch, M. T.; Ayliffe, L. K. (8 January 1999). "Pleistocene Extinction of Genyornis newtoni: Human Impact on Australian Megafauna". Science. 283 (5399): 205–208. doi:10.1126/science.283.5399.205. PMID 9880249.

- ^ Miller, Gifford; Magee, John; Smith, Mike; Spooner, Nigel; Baynes, Alexander; Lehman, Scott; Fogel, Marilyn; Johnston, Harvey; Williams, Doug; Clark, Peter; Florian, Christopher; Holst, Richard; DeVogel, Stephen (2016). "Human predation contributed to the extinction of the Australian megafaunal bird Genyornis newtoni ~47 ka". Nature Communications. 7: 10496. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710496M. doi:10.1038/ncomms10496. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4740177. PMID 26823193.

- ^ Worthy, Trevor H. A case of mistaken identity for Australia's Extinct Big Bird The Conversation, 14 January 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Grellet-Tinner, Gerald; Spooner, Nigel A.; Worthy, Trevor H. (February 2016). "Is the Genyornis egg of a mihirung or another extinct bird from the Australian dreamtime?". Quaternary Science Reviews. 133: 147–164. Bibcode:2016QSRv..133..147G. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.12.011. hdl:2328/35952.

- ^ "First Australians ate giant eggs of huge flightless birds". University of Cambridge. 25 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Demarchi, Beatrice; Stiller, Josefin; Grealy, Alicia; Mackie, Meaghan; Deng, Yuan; Gilbert, Tom; Clarke, Julia; Legendre, Lucas J.; Boano, Rosa; Sicheritz-Pontén, Thomas; Magee, John (24 May 2022). "Ancient proteins resolve controversy over the identity of Genyornis eggshell". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (43): e2109326119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11909326D. doi:10.1073/pnas.2109326119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 9995833. PMID 35609205. S2CID 249045755.

- ^ Bradshow, Corey J.A.; et al. (30 March 2021). "Relative demographic susceptibility does not explain the extinction chronology of Sahul's megafauna". eLife. 10. doi:10.7554/eLife.63870. PMC 8043753. PMID 33783356.

- ^ "Megafauna cave painting could be 40,000 years old". www.abc.net.au. 31 May 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2010.; Gunn, R. C.; et al. (2011). "What bird is that?". Australian Archaeology. 73: 1–12.

- ^ Rupert Gerritsen (2011) Beyond the Frontier: Explorations in Ethnohistory, Canberra: Batavia Online Publishing. pp.52-69 ISBN 978-0-9872141-4-0

- ^ Barker, Bryce; Lamb, Lara; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques; David, Bruno; Gunn, Robert; Chalmin, Emilie; Castets, Géraldine; Aplin, Ken; Sadier, Benjamin (30 November 2017), David, Bruno; Taçon, Paul; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques; Geneste, Jean-Michel (eds.), "Archaeology of JSARN–124 site 3, central-western Arnhem Land: Determining the age of the so-called 'Genyornis' painting" (PDF), The Archaeology of Rock Art in Western Arnhem Land, Australia (1st ed.), ANU Press, doi:10.22459/ta47.11.2017.15, ISBN 978-1-76046-161-4, retrieved 9 May 2023

- ^ Chalmin, Émilie; Castets, Géraldine; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques; David, Bruno; Barker, Bryce; Lamb, Lara; Soufi, Fayçal; Pairis, Sébastien; Cersoy, Sophie; Martinetto, Pauline; Geneste, Jean-Michel; Hoerlé, Stéphane; Richards, Thomas; Gunn, Robert (February 2017). "Geochemical analysis of the painted panels at the "Genyornis" rock art site, Arnhem Land, Australia". Quaternary International. 430: 60–80. Bibcode:2017QuInt.430...60C. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.04.003.

- ^ Cobden, Rommy; Clarkson, Chris; Price, Gilbert J.; David, Bruno; Geneste, Jean-Michel; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques; Barker, Bryce; Lamb, Lara; Gunn, Robert G. (November 2017). "The identification of extinct megafauna in rock art using geometric morphometrics: A Genyornis newtoni painting in Arnhem Land, northern Australia?". Journal of Archaeological Science. 87: 95–107. Bibcode:2017JArSc..87...95C. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2017.09.013.

- ^ McInerney, P.L.; Arnold, L.J.; Burke, C.; Camens, A.B.; Worthy, T.H. (2022). "Multiple occurrences of pathologies suggesting a common and severe bone infection in a population of the Australian Pleistocene giant, Genyornis newtoni (Aves, Dromornithidae)". Papers in Palaeontology. 8. doi:10.1002/spp2.1415. S2CID 245257837.

- Stirling, E. C.; Zietz, A. H. C. (1913). "Description of some further remains of Genyornis newtoni" (PDF). Memoirs of the Royal Society of South Australia. Fossil remains of Lake Callabonna. 1 (4): 111–126.