Summary

Hempstead is a city in and the county seat of Waller County, Texas, United States,[4] part of the Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land metropolitan area.

City of Hempstead, Texas | |

|---|---|

Hempstead City Hall | |

| Nickname: Watermelon Capital of Texas | |

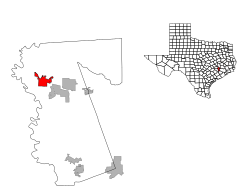

Location in the state of Texas | |

| Coordinates: 30°5′29″N 96°4′53″W / 30.09139°N 96.08139°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Waller |

| Incorporated | Originally incorporated November 10, 1858, re-incorporated June 10, 1935 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Erica Gillum |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.56 sq mi (16.99 km2) |

| • Land | 6.55 sq mi (16.97 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 227 ft (69.1 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 5,430 |

| • Density | 1,275.38/sq mi (492.42/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 77445 |

| Area code | 979 |

| FIPS code | 48-33200[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1337592[3] |

| Website | hempsteadcitytx |

History edit

On December 29, 1856, Dr. Richard Rodgers Peebles and James W. McDade organized the Hempstead Town Company to sell lots in the newly established community of Hempstead, which was located at the projected terminus of Houston and Texas Central Railway. Peebles named Hempstead after Dr. G. S. B. Hempstead, Peebles's brother-in-law. Peebles and Mary Ann Groce Peebles, his wife, contributed 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of the estate of Jared E. Groce, Jr., for the community. On June 29, 1858, the Houston and Texas Central Railway was extended to Hempstead, causing the community to become a distribution center between the Gulf Coast and the interior of Texas. On November 10 of that year, Hempstead incorporated. The Washington County Railroad, which ran from Hempstead to Brenham, enhanced the city upon its completion.[5]

The Civil War and aftermath edit

1861–1862 edit

The Confederate Military Post of Hempstead was established in the spring of 1861. Numerous camps of instruction were established east of town along Clear Creek. Camp Hebert was established on the eastern bank of Clear Creek and south of Washington Road. Camp Hebert was the earliest camp in the area, and served as the headquarters of the Post of Hempstead early in the war.

Camp Groce CSA was established in the spring of 1862 on Liendo Plantation on the eastern bank of Clear Creek as a camp of instruction for Confederate infantry recruits. Originally named Camp Liendo, the name was changed to Camp Groce in honor of Leonard Waller Groce, the owner of Liendo Plantation,[6] and the owner of over 100 slaves. A contract to construct the barracks at Camps Groce and Hebert was let in February 1862. Numerous Confederate infantry regiments were organized, trained, and equipped at Camps Groce and Hebert. In the spring of 1862, the camps were abandoned due to their sickness-inducing locations. Camp Groce was reused as a military camp until spring 1863, but was again abandoned. From 1861 to 1863, nearly 200 Confederate soldiers fell sick at Camps Groce and Hebert and died. Many were taken to the Post Hospital in the Planter's Exchange Hotel located at the southwest corner of 12th and Wilkins Streets in downtown Hempstead. Many died in the hospital and almost all of them are buried on McDade Plantation west of town, which became the hospital cemetery.

1863 edit

In June 1863, Camp Groce was reopened as a prison camp for Union prisoners captured in the Battles of Galveston (January 1, 1863) and Sabine Pass I (January 21, 1863). The Union prisoners of war taken at the Battle of Sabine Pass II (September 8, 1863) were also sent to Camp Groce; 427 Union prisoners were held at Camp Groce in 1863 and 21 died. Most of the dead were buried northeast of camp where most of them still rest today.[7]

1864 edit

Camp Groce was reopened in May 1864 for 148 Union prisoners captured at the battle of Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana. The prisoners included the crew of the USS Granite City and USS Wave, Tinclad #45, and 37 soldiers. About 40 soldiers from the 1st Texas US Cavalry were sent to Camp Groce in June 1864, and 506 more Union prisoners were transferred to Camp Groce from Camp Ford in August 1864. Yellow fever and other diseases affected the prisoners. They were moved to Camp Gillespie near Bellville in late September 1864 and then to Camp Felder, 6.5 miles north-northwest of Chappell Hill, Texas; 221 prisoners died or were missing from Camps Groce, Gillespie, and Felder in 1864, and 444 were paroled in December 1864.

1863: 427 POWs, 21 died, 2 escaped

1864: 683 POWs, 147 died, 28 missing, 18 escaped, 13 deserted to the enemy, 14 status unknown, and 1 political prisoner held by CS authorities until released in May 1865.

Totals: 1,110 POWs held, 168 died, 28 missing, 20 escaped, 13 deserted to the enemy, 14 status unknown

At least 277 Confederate soldiers died or went missing in and around Hempstead during the Civil War.

Most of the US and CS soldiers who died in and around Hempstead during the Civil War are still buried in the area. They are buried in three primary locations in and around Camp Groce and west of town on the old McDade Plantation Cemetery on Austin Branch Road near Sorsby Road. A Texas State Historical Marker there is entitled "Union Army POW Cemetery" but numerous US Navy POWs are also buried there, along with numerous Confederate soldiers who died in the hospitals in downtown Hempstead.

Recently, a Waller County Historical Marker was placed within the boundaries of Camp Groce. It is located on the east side of FM 359 just south of Clear Creek. Entitled "Camp Groce Cemetery", the marker commemorates the deaths and burial location of US prisoners of war and Confederate soldiers who died and were buried within the boundaries of Camp Groce. Also, the Washington County Historical Commission has placed a Texas State Historical Marker entitled, "Camp Felder" on the west side of FM 1155 north of Chappell Hill, Texas, to commemorate Camp Felder CSA.

1865 edit

About 8,000 Confederate soldiers from Walker's Division (commanded by Maj. Gen. John H. Forney) were ordered to Hempstead from Louisiana in March 1865. Upon the arrival of the division on March 24–30, 1865, the soldiers began waiting for Confederate President Jefferson Davis to arrive to make the Last Stand of the Confederacy at Hempstead. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, Johnston surrendered on April 26, 1865, and Davis was captured in Georgia on May 10, 1865, all of which compelled Confederate Maj. Gen. Kirby Smith to surrender the Department of the Trans-Mississippi on June 2, 1865. All Confederate forces in Hempstead and all other CS posts in Texas mostly went home. Immediately after the surrender of CS forces in Texas, about a month was needed before US troops entered the state. The first US force to arrive in Hempstead after the war was the 29th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The 29th was relieved by the 37th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment that garrisoned the US Post of Hempstead well into 1866.

In August 1865, Maj. Gen. George A. Custer arrived in Hempstead with a division of volunteer US cavalry. The division camped in and around Liendo Plantation for about two months before moving to Austin or were mustered out of the service at Hempstead in 1865–66. The cavalry regiments under the command of Custer at Hempstead were the 1st Iowa, 2nd Wisconsin, 7th Indiana, and the 5th and 12th Illinois Cavalries. Company K of the 37th Illinois Volunteer Infantry occupied the town and guarded the railroad line until the regiment was mustered out in May 1866. The headquarters of the US Post of Hempstead was located in town and not at Liendo Plantation.

US Forces fanned out and set up camps in numerous towns. Their mission was to parole former Confederate troops, collect CS property, and to establish law and order. Many former CS troops did not report for their paroles, however, and many went to Mexico. The volunteer US regiments stationed in Texas were nearly gone from the state by the end of 1865.

1866–1869 edit

In 1866, the 1st Battalion, Companies A and B of the 17th US Infantry, was stationed at Hempstead. The battalion arrived for duty in Hempstead in the fall of 1866. They set up camp north of the US Post Office in downtown Hempstead. Their mission was primarily in support of the Freedmen's Bureau. In the fall of 1867, a yellow-fever epidemic devastated the civilian population of Hempstead, and nearly 40 soldiers of the 17th US Infantry died, as well.

1873 edit

German-American sculptor Elisabet Ney and her husband, Scottish physician and philosopher Edmund Montgomery, purchased the Liendo plantation where their family and they split time between there and their home in Austin for the next 20 years. Ney died and was buried at Liendo.[8]

20th century to present edit

Hempstead is famous for its watermelon crop, and until the 1940s, the town was the top shipper of watermelons in the United States. Billy DiIorio was known as the Watermelon King and Angelina DiIorio was known as the Watermelon Queen. Both resided in Hempstead. The town holds an annual Watermelon Festival in July.[9]

Hempstead is also known for its early 20th-century rough-and-tumble character. The town was informally called Six Shooter Junction.[10]

The town has grown in recent years because of its relative closeness to Houston along U.S. Highway 290. The current economy is based on county government, shipping, and a small but growing industrial base. The town has rebounded in its population since 2010.

One of the town's residents was Lillie E. Drennan, who in 1929 became the first woman to hold a commercial driver's license in Texas. She ran a regional hauling company called the Drennan Truck Line while maintaining an excellent driving record. Drennan received periodic attention in national newspapers and radio broadcasts.[11]

Geography edit

Hempstead is located at 30°5′29″N 96°4′53″W / 30.09139°N 96.08139°W (30.091427, –96.081252).[12] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.0 square miles (12.9 km2), of which 0.04 square mile (0.1 km2) (0.40%) is covered by water.

Location edit

The community, located at the junctions of U.S. Highway 290, Texas State Highway 6, and Texas State Highway 159, is about 50 miles northwest of downtown Houston.[5] The population was 5,770 at the 2010 census.[13]

Highways edit

Demographics edit

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,612 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,671 | 3.7% | |

| 1940 | 1,674 | — | |

| 1950 | 1,395 | −16.7% | |

| 1960 | 1,505 | 7.9% | |

| 1970 | 1,891 | 25.6% | |

| 1980 | 3,456 | 82.8% | |

| 1990 | 3,551 | 2.7% | |

| 2000 | 4,691 | 32.1% | |

| 2010 | 5,770 | 23.0% | |

| 2020 | 5,430 | −5.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 1,150 | 21.18% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1,760 | 32.41% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 10 | 0.18% |

| Asian (NH) | 31 | 0.57% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 3 | 0.06% |

| Some other race (NH) | 10 | 0.18% |

| Mixed/multiracial (NH) | 91 | 1.68% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2,375 | 43.74% |

| Total | 5,430 |

As of the 2020 United States census, 5,430 people, 2,777 households, and 1,734 families resided in the city.

As of the census[18][19] of 2010, 5,770 people, 2,010 households, and 1,360 families resided in the city. The population density was 1,040.8 inhabitants per square mile (401.9/km2). The 2,220 housing units averaged 400.7 per square mile (154.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 36.8% White (including 22.5% non-Hispanic/Latino), 38.9% African American, 1.4% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 20.2% from other races, and 2.2% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 37.4% of the population.

Of the 2,010 households, 36.4% had children under 18 living with them, 37.7% were married couples living together, 22.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.3% were not families. About 25.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.81, and the average family size was 3.42.

In the city, the population was distributed as 30.6% under 18, 14.7% from 18 to 24, 25.3% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 9.3% who were 65 or older. The median age was 27.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 95 males. For every 100 females 18 and over, there were 90.4 males.[20]

The median income for a household in the city was $35,859. In 2008–2012, the per capita income for the city was $15,888. About 25.4% of the population was below the poverty line.

Economy edit

Until February 2009, the Lawrence Marshall car dealership was Hempstead's largest employer. The sudden closure of the dealership led the city to reconsider capital projects such as sewer upgrades and city park upgrades.[21]

Government and infrastructure edit

Hempstead is the county seat of Waller County. The United States Postal Service Hempstead Post Office is located at 901 12th Street.[22]

The Hempstead Police Department was established in 1981, replacing the town marshal. It has 19 full-time and five reserve officers.[23] In early 2007, the Department's head, R. Glenn Smith, was given a two-week, unpaid suspension and six months probation because of allegations that four officers and he, all White, had exhibited racism and police brutality during the arrest of a 35-year-old Black man. In March 2008, he was fired by the town council. He then ran for and was elected sheriff of Waller County.[24]

In February 2009, the mayor pro tem and an alderman resigned as a result of an investigation into bribery and kickbacks in awarding contracts.[25]

Education edit

The City of Hempstead is served by the Hempstead Independent School District.

The one private Christian school in Hempstead is the Community Christian Academy. The grades of study offered are kindergarten through fifth grade.

Climate edit

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen climate classification, Hempstead has a humid subtropical climate, Cfa on climate maps.[26]

References edit

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Hempstead, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ^ Clampitt, Brad. "Camp Groce". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Clampitt, Brad. "Camp Groce". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Ney, Elisabet (1833–1907).

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Hempstead, TX: Chamber of Commerce. Watermelon Festival". Archived from the original on April 5, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ "Hempstead, TX". www.tshaonline.org.

- ^ Lucko, Paul. "Drennan, Lillie Elizabeth McGee". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Counts, 2010 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). Texas: 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/ [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Hempstead (City) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Archived from the original on August 7, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Bureau, U. S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Turner, Allan. "Hempstead comes to grips without big employer." Houston Chronicle. February 5, 2009. Retrieved on February 7, 2009.

- ^ "Post Office Location - HEMPSTEAD." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on December 6, 2008.

- ^ "Hempstead Police Department". Hempstead Police Department. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Foxhall, Emily. "Waller County sheriff seeks 3rd term after difficult year". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Federal probe exposes corruption in Texas county". Palestine Herald. Associated Press. May 24, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ "Hempstead, Texas Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

External links edit

- City of Hempstead

- Hempstead, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online