Summary

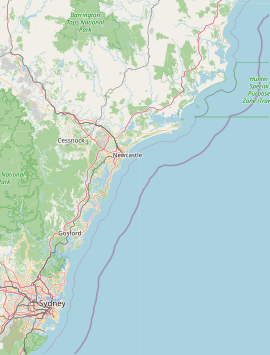

Hexham /ˈhɛks.əm/ is a suburb of the city of Newcastle, about 15 km (9 mi) inland from the Newcastle CBD in New South Wales, Australia on the bank of the Hunter River.[2][7]

| Hexham Newcastle, New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Ozzie the Mozzie" at Hexham Bowling Club | |||||||||||||||

Hexham | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°49′54″S 151°41′4″E / 32.83167°S 151.68444°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 130 (2016 census)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 8.1/km2 (21/sq mi) Note1 | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1820s | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2322 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft)Note2 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 18.7 km2 (7.2 sq mi)Note3 | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11) | ||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | City of Newcastle[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Hunter[2] | ||||||||||||||

| County | Northumberland[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Parish | Hexham[3] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Newcastle[6] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

History edit

Settlement occurred at Hexham in the 1820s when the land was granted to Edward Sparke.[citation needed] Hexham was named after the market town of Hexham, England with both towns being near to a Newcastle and sharing a history with one another; many of the coal miners from Newcastle upon Tyne and elsewhere in Northumberland moved to New South Wales at the time of settlement.

The history of Hexham is closely associated with that of the nearby suburbs of Tarro (originally Upper Hexham), Ash Island, Tomago and Minmi.

Geography edit

Hexham measures approximately 6.7 km (4.2 mi) from north to south and 6 km (3.7 mi) from east to west, covering an area of 18.7 square kilometres (7.2 sq mi). The suburb is bordered to the east by the Hunter River - Coquun and by Ironbark Creek - Toohrnbing[8] to the south, while to the west the suburb consists mainly of unproductive swampland and floodplains. Almost all settlement exists within a narrow corridor stretching along the Pacific Highway between the Main Northern railway line and the Hunter River - Coquun. This corridor, which is occupied mainly by highways and industrial areas, covers an area of only 1.1 square kilometres (0.4 sq mi). Within the zone residential development is confined to 3 small areas measuring only 0.137 square kilometres (0.053 sq mi) in total.[7] On Maitland Road there is Hexham Park which has a number of facilities including a cricket pitch, rugby union field, lights, amenities and a grandstand.[9]

Transport edit

Roads edit

Hexham is located at the junction of the Pacific Highway to Brisbane via the coastal route, the New England Highway and is close to the northern end of the Pacific Motorway. The Hunter Valley Dairy Co-operative took advantage of this key location to establish its first milkbar under the Co-operative's signature dairy brand Oak to serve locals and longer distance travellers outside its Hexham manufacturing facility. Many years after the closure of the co-operative and the sale of the Oak milk brand Lion to Parmalat, the Hexham manufacturing site now operated and owned by Brancourts is often referred to as the "old Oak site".

Hexham is located just upstream of the Hunter River delta and its various islands, and as such it was a relatively convenient place for crossing to the north bank of the river. A punt was established in the 1800s, followed by a steam punt, which eventually carried motor traffic. As traffic levels grew after World War I, Hexham became a bottleneck for road traffic. A decision was made in the late 1930s to construct a bridge, however construction was delayed by World War II. Eventually the first two-lane bridge was opened in December 1952.[10][11] The first bridge is a steel truss bridge with a central lifting span, designed to allow shipping to travel upstream. By the 1970s, this bridge was becoming a bottleneck and the decision was made to increase capacity by building a second bridge for all northbound traffic. This concrete high-level fixed bridge was built just upstream of the original bridge (converted to carry southbound traffic only) and was opened in August 1987.[12][13]

Railways edit

Hexham has its own railway station on the Main Northern railway line, served by an hourly NSW TrainLink service between Newcastle and Maitland/Telarah for a majority of the day.[14] It was the riverine terminus of the privately owned Richmond Vale Railway line, an early coal hauling railway from Minmi and Stockrington which crossed the Main Northern railway line at right angles. Coal loading at the wharf ended in 1967 and the railway line to the adjoining workshops was closed in October 1973. The remaining section of the Richmond Vale Railway was closed in September 1987.[15]

Shipping edit

Hexham was once a riverport of some importance in the lower Hunter and was known as Port Hunter, dual named Yohaaba.[16] In the colonial days travellers from Newcastle to Maitland could travel to Hexham by boat and then disembark to travel by road to Maitland via Upper Hexham (Tarro), Four Mile Creek and Green Hills, the road being more direct than the river which had many bends after Raymond Terrace. Coal loading at Hexham began about 1850.

One timber wharf was located on the south bank, downstream of the first Hexham bridge. This was originally used by J & A Brown from the mid-1800s to load coal brought by train from Minimi across Hexham Swamp - Burraghihnbihng.[17] As J & A Brown's operations expanded coal was loaded at this wharf from their other coal mines. Coal arrived via the Richmond Vale Railway and a right-angle crossing (across the Main North government line) from 1856 until November 1967.[18] Around 1890, this facility was loading cargoes of up to 610 t (600 long tons) at a rate of 1,016 t (1,000 long tons) per day. Coal for ships with larger cargos was sent from Hexham to other ports using the government rail line.[19] There was a large rail yard called the Hexham Exchange Sidings to allow J & A Brown coal trains to be taken over the government line to Carrington. The Hexham Coal Washery, opened in 1953, remained operating after the coal loader closed.[18] Ship loading at the J & A Brown shiploader ended on 1 November 1967.[15] The last ship loaded was the MV Stephen Brown.

A shiploader served by road adjacent the road bridge over the Hunter River - Coquun[20] was constructed by J & A Brown Abermain Seaham Collieries Ltd at their Hexham Engineering Workshops in 1959 for RW Miller.[21] After the merger of RW Miller with Coal & Allied in the mid-1980s, it was used by Coal & Allied to load coal washed at the Hexham Coal Washery destined for Sydney. This loader was closed in 1988 after the closure of the Hexham Coal Washery.,[18] The last ship to load there – and after 138 years, the last to load coal at Hexham – was the MV Camira in May 1988.[22] and the loader was dismantled soon afterwards..

Another timber wharf was located on the south bank about 600 m (1,969 ft) upstream from the current bridges across the Hunter River - Coquun.[23] This was near the Wheatsheaf Hotel, once operated by John Hannell, whose tomb is nearby. The loader was built in 1935 for the Hetton Bellbird Collieries and was sold to the Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company in 1956. It was supplied via the South Maitland Railway up to the East Greta Exchange Sidings (near Maitland) and from there via the Main Northern railway line to the Hetton Bellbird Sidings at the loader. It had 10 'full' and 5 'empty' sidings. The coal was dumped at a dump station and was transferred via conveyor across the main line and highway to a ship-loader.[18](The company has a depot to the west, across the Pacific Highway and Great North Railway, at the end of what is now Woodlands Road.) After it was constructed, the first Hexham bridge was built in 1952 with a centre lifting span so small ships could travel to this wharf. (Similarly, the Stockton Bridge further downstream was built with a high arch so ships could travel upstream to Hexham by the north channel of the Hunter River - Coquun to load coal at Hexham.) This loader was later taken over by Peko-Wallsend in the 1960s, which also built six 610 t (600 long tons) coal silos (painted green) on the river bank and conveyors across the railway and highway to expedite loading. The loader was closed in 1972 and demolished during 1976.[18] The MV Hexham Bank was the last ship to be loaded at the Peko-Wallsend loader in November 1971,[22] The wharf was demolished by the 1990s.

The ships serving Hexham were small and known as 60 milers, based on the distance they travelled to Sydney carrying coal for gas-making or to the coal depot at Blackwattle Bay. In Hexham's later days as a port, ships sometimes ran aground travelling from Hexham.[24]

Milk was also transported by small boats to the Hunter Valley Dairy Co-operative factory after it was opened at Hexham in 1927.

Industries edit

Hexham's central location, with ready access to river, road and rail transport, has made it a key crossroads in the lower Hunter and influenced its industries. Originally it was a site of farming by the Sparke family. As a crossroads, hotels soon followed, with three in operation in the 1800s: the Wheatsheaf, Hexham and Travellers Rest.

Later it was a key locality for coal loading by J & A Brown and the Bellbird-Hetton Colliery. With coal loading came coal washeries and engineering workshops.

Its central location was again important to the establishment in 1927 of a dairy processing factory by the Hunter Valley Dairy Co-operative, which established the Oak milk brand. The site is now owned and operated by Brancourts Dairy; one of the oldest Australian owned and operated dairy companies in Australia.[25][26]

Hexham's central location has seen the establishment of petrol stations, fast food outlets, warehouses and saleyards for heavy vehicles and caravans.

The Hexham Bowling Club provides a range of entertainment services for locals and travellers.

It is also the home of the Free Church of Tonga which is situated on Old Maitland Road.

People edit

In the 2016 census, Hexham recorded a population of 130 people.[1] The median age of residents was 50 years, compared to the national median of 38 years. People aged 65 years and over made up 26% of the population, compared to the national average of 16%. The majority (85%) were born in Australia, compared to the national average of 67%; the next most common countries of birth were Pakistan 3.1% and England 2.3%.

Mosquitoes edit

The mosquito species Ochlerotatus alternans is common in the area and adults, famed for their size and ferocity, are referred to as "Hexham Greys".[27] The most famous Hexham Grey is "Ossie the Mossie", (sometimes spelled as "Ozzie the Mozzie") a large model of a mosquito that sits atop the Hexham Bowling Club sign at the corner of the Pacific Highway and Old Maitland Road in Hexham. The Hexham Bowling Club's "retired" bowlers are affectionately known as the "Hexham Greys".[28] The previous "Ossie" was replaced with a new "Ossie" (pictured) in 2005.[29] Ozzie disappeared from the sign in early February 2010 and was replaced in April 2010.

Notes edit

- ^ The density presented is that of the whole suburb. However, almost all of the population resides in only about 0.13 square kilometres (0.05 sq mi), or about 0.7%, of the suburb. Most of the suburb consists of unpopulated swampland with some industrial areas between the Pacific Highway and the Hunter River.[7] The population density of the residential portion of the suburb is much higher at 1,126/km2 (2,920/sq mi).

- ^ Average elevation of the suburb as shown on 1:100000 map 9232 NEWCASTLE.

- ^ Area calculation is based on 1:100000 map 9232 NEWCASTLE.

References edit

- ^ a b Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Hexham (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ a b c "Suburb Search – Local Council Boundaries – Hunter (HT) – Newcastle City Council". New South Wales Division of Local Government. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ a b "Hexham". Geographical Names Register (GNR) of NSW. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "Wallsend". New South Wales Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ "Cessnock". New South Wales Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ "Newcastle". Australian Electoral Commission. 19 October 2007. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ a b c "Hexham". Land and Property Management Authority - Spatial Information eXchange. New South Wales Land and Property Information. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "Media Release, Indigenous Naming Comes To Newcastle" (PDF). Geographical Names Board NSW Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Hexham". City of Newcastle. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Vital Bridge Link Opened Newcastle Sun 17 December 1952 page 1

- ^ Bridge Opened at Hexham Sydney Morning Herald 18 December 1952 page 5

- ^ The Hexham Bridge Duplication Project Main Roads March 1984 pages 11-14

- ^ Annual report year ended 30 June 1988 Department of Main Roads page 19

- ^ "Hunter line timetable". Transport for NSW.

- ^ a b Andrews, Brian Robert (2007). Coal, Railways and Mines – The Story of the Railways and Collieries of J & A Brown. Iron Horse Press. ISBN 978-0-909650-63-6.

- ^ "Media Release, Indigenous Naming Comes To Newcastle" (PDF). Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Media Release, Indigenous Naming Comes To Newcastle" (PDF). Geographical Names Board NSW Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Help with defunct NSW branch at Hexham". Railpage. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Kingswell, George H. (1890). The Coal Mines of Newcastle, NSW – Their Rise and Progress (PDF). p. 28.

- ^ "Media Release, Indigenous Naming Comes To Newcastle" (PDF). Geographical Names Board NSW Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Andrews, Brian Robert (2009). Coal, Railways and Mines – The Colliery Railways of the Newcastle District and the Early Coal Shipping Facilities – Volume 2. Iron Horse Press. ISBN 978-0-9805106-7-6.

- ^ a b RAY, GREG (2 August 2013). "GREG RAY: Pictures of the past". Newcastle Herald. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "Media Release, Indigenous Naming Comes To Newcastle" (PDF). Geographical Names Board NSW Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Old sea tales of the 'sixty-milers'". Newcastle Herald. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "Brancourts | Business World Australia".

- ^ "Brancourts | About us". www.brancourts.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Mosquito Photos Ochlerotatus alternans". NSW Health. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ "The Big Mozzie at Hexham Newcastle N.S.W". webshots travel. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ^ "Ozzie the Mozzie buzzes back in to town". Shortland Pipeline (newspaper). 24 April 2007. p. 2. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "Newcastle Nobbys Signal Station AWS". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 18 June 2008.