Summary

Honora Edgeworth (née Sneyd;[b] 1751 – 1 May 1780) was an eighteenth-century English writer, mainly known for her associations with literary figures of the day particularly Anna Seward and the Lunar Society, and for her work on children's education. Sneyd was born in Bath in 1751, and following the death of her mother in 1756 was raised by Canon Thomas Seward and his wife Elizabeth in Lichfield, Staffordshire until she returned to her father's house in 1771. There, she formed a close friendship with their daughter, Anna Seward. Having had a romantic engagement to John André and having declined the hand of Thomas Day, she married Richard Edgeworth as his second wife in 1773, living on the family estate in Ireland till 1776. There she helped raise his children from his first marriage, including Maria Edgeworth, and two children of her own. Returning to England she fell ill with tuberculosis, which was incurable, dying at Weston in Staffordshire in 1780. She is the subject of a number of Anna Seward's poems, and with her husband developed concepts of childhood education, resulting in a series of books, such as Practical Education, based on her observations of the Edgeworth children. She is known for her stand on women's rights through her vigorous rejection of the proposal by Day, in which she outlined her views on equality in marriage.

Honora Sneyd | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1751 Bath, Somerset, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Died | 1 May 1780 (aged 28–29) Weston-under-Lizard, Staffordshire, Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Resting place | Weston-under-Lizard, Staffordshire, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Life edit

Early life 1751–1773 edit

Honora Sneyd was born the third daughter to Edward Sneyd who lived in Bishton, Staffordshire[11] and Susanna Cook of Sible Hedingham, Essex, in Bath in 1751.[c] Her father was a Major in the Royal Horse Guards,[12] with an appointment at Court as a Gentleman Usher.[13] her parents married in 1742[14] and she was one of eight children and the second surviving daughter of six, and only six years old when her mother died in 1757.[15][16] Her father found himself unable to take care of all of his children and various friends and relations then offered to take them in.[13][17]

Adoption by the Seward family 1756–1771 edit

Honora Sneyd, who was seven years younger than the thirteen-year-old Anna Seward,[17] moved into the home of family friends, Canon Thomas Seward and his wife Elizabeth and their family at Lichfield, Staffordshire, where they lived in the Bishop's Palace in the Cathedral Close.[18] The Sewards had lost five children after their first two daughters, and such fostering was not uncommon at the time.[19] There she was brought up by the Sewards as one of their own, being variously described as an adopted or foster sister.[13][20][21] Anna Seward describes how she and her younger sister Sarah first met Honora, on returning from a walk, in her poem The Anniversary (1769).[d][22] Initially Honora was more attached to Sarah,[23] to whom she was closer in age, but Sarah died of typhus at the age of nineteen (1764), when Honora Sneyd was thirteen. Following Sarah's death Honora became the responsibility of Anna, the older sister.[24] Anna consoled herself with her affection for Honora Sneyd, as she describes in Visions, written a few days after her sister's death. In the poem she expresses the hope that Honora ('this transplanted flower') will replace her sister (whom she refers to as 'Alinda') in her and her parents' affections.[25] Throughout her life Honora Sneyd's health was fragile, experiencing the first bout of the tuberculosis that would later claim her life in 1766, at the age of fifteen.[26] However, Anna Seward believed she detected the first signs in 1764, at thirteen, writing presciently

This dear child will not live; I am perpetually fearing it, notwithstanding the clear health which crimsons her cheek and glitters in her eyes. Such early expansion of intelligence and sensibility partakes too much of the angelic, too little of the mortal nature, to tarry long in these low abodes of frailty and of pain, where the harshness of authority, and the impenetrability of selfishness, with the worse mischiefs of pride and envy, so frequently agitate by their storms, and chill by their damps, the more ingenious and purer spirits, scattered, not profusely, over the earth.[27]

Education edit

At Lichfield Honora Sneyd came under the influence of Canon Seward, who raised her, and his progressive views on female education, which he expressed in his poem The Female Right to Literature (1748).[28] She was described as clever and interested in science,[29] From Anna she developed a great love of literature.[24]

Honora Sneyd was an accomplished scholar, attending day school in Lichfield where she became fluent in French, translating Rousseau's Julie for her older foster sister.[17] Though Canon Seward's (but not his wife's) attitudes towards the education of girls was progressive relative to the times, they were "by no means excessively liberal". Amongst the subjects he taught them were theology and numeracy, and how to read, appreciate, write and recite poetry. Although this deviated from what were considered "conventional drawing room accomplishments", he encouraged them away from traditional female roles. However, the omissions were also notable, including languages and science, although they were left free to pursue their own inclinations in this regard.[17] To that end they were exposed to the circle of learned men who frequented the Bishop's Palace at Lichfield where they lived, and which became the centre of a literary circle including, David Garrick, Erasmus Darwin, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell.[30] The children were encouraged to participate in the conversations, as Anna later relates.[e][20][30][32]

Relationships edit

Honora Sneyd and Anna Seward lived under the same roof for thirteen years and formed a close friendship which has given rise to much speculation as to its exact nature,[33] located as it was within the tradition of "female friendship", and forming the basis of a body of Anna Seward's poetical works.[34] Various authors differ in their interpretation of the relationship between the two women, with Lillian Faderman who first suggested that it was lesbian,[35] supported by Barrett[36] although the term relates more to twentieth- rather than eighteenth-century concepts of identity. On the other hand, Teresa Barnard argues against this based more on examination of the correspondence rather than poetry, which is generally based within the lesbian poetic canon, the relationship between these two women being frequently cited.[32]

Sneyd had a reputation for both intelligence and beauty,[13] as commented on by many, including Anna Seward[37] and Richard Edgeworth[38] (see below).[39][40] In 1764 Seward described Sneyd as "fresh and beautiful as the young day-star, when he bathes his fair beams in the dews of spring".[27] At seventeen[25] Honora Sneyd was briefly engaged to a Swiss born Derbyshire merchant, John André,[41] a relationship that Seward had fostered, and wrote about in her Monody on Major André (1781)[42][43] when André became a British officer in 1771 and was hanged as a spy by the Americans.[f] The respective parents did not support this attachment for reasons of his financial status.[45]

Around Christmas 1770, Thomas Day and Richard Edgeworth, who like Thomas Seward were members of the Lunar Society that met in Lichfield amongst other places,[46] were spending increasing amounts of time at the Seward household and both had fallen for Sneyd, although Edgeworth was already married.[38] In 1771 she declined an offer of marriage from Thomas Day.[47] Edgeworth gives an account of her letter of rejection stating that it "contained an excellent answer to his [Day's] arguments in favour of the rights of men, and a clear dispassionate view of the rights of women". Edgeworth continues that Sneyd had very determined views on the role of women and their rights within marriage.[48]

Miss Honora Sneyd would not admit the unqualified control of a husband over all her actions; she did not feel, that seclusion from society was indispensably necessary to preserve female virtue, or to secure domestic happiness. Upon terms of reasonable equality, she supposed, that mutual confidence might best subsist; she said, that, as Mr Day had decidedly declared his determination to live in perfect seclusion from what is usually called the world, it was fit she should decidedly declare, that she would not change her present mode of life, with which she had no reason to be dissatisfied, for any dark and untried system, that could be proposed to her.[49]

However, Honora Sneyd's father moved to Lichfield from London in 1771, and reassembled his family of five daughters there. By now Honora was nineteen and Anna viewed her friend's departure with considerable dismay.[50] Although Day was much distressed by his rejection by Honora Sneyd, he transferred his affections to the fifth daughter, Elizabeth Sneyd, who had been in the care of Mr Henry Powys and his wife, Susannah Sneyd,[51] of the Abbey,[52] Shrewsbury, Mrs. Powys being Mr Sneyd's niece.[53][29][54][55][g] However, Elizabeth Sneyd was not inclined to accept Day.[58]

Richard Edgeworth comments on how Honora Sneyd had affected him;

During this intercourse I perceived the superiority of Miss Honora Sneyd's capacity ... her sentiments were on all subjects so just and were delivered with such blushing modesty though not without an air of conscious worth as to command attention from every one capable of appreciating female excellence. Her person was graceful her features beautiful and their expression such as to heighten the eloquence of every thing she said. I was six and twenty and now for the first time in my life I saw a woman that equalled the picture of perfection which existed in my imagination.[38]

He continued, describing the unhappiness of his marriage, and how that made him vulnerable to her attributes, which were shared by all the learned gentlemen of his circle. He also believed that Anna Seward had noticed the effect her friend was having on him, and would regularly place her actions in the best light for his benefit.[43] The elimination of Day as a suitor for Honora Sneyd's hand placed Edgeworth in a difficult situation and he resolved to end it by moving to Lyons France, to work, in the autumn of 1771.[59]

Marriage to Richard Edgeworth 1773–1780 edit

Marriage and move to Ireland 1773–1776 edit

On 17 March 1773, Edgeworth's first wife Anna Maria Elers gave birth to their fifth child, Anna Maria Edgeworth, at the age of 29. Ten days later she died from puerperal fever.[60][61][62][h] Edgeworth was still in Lyon to avoid temptation[59] leaving his expectant wife in the care of Day. On learning of the death of his wife, Edgeworth travelled to London, where he consulted Day as to Honora Sneyd's situation. On learning that she remained in good health and unattached, he promptly headed to Lichfield to see Honora at the Sneyds, with the intention of proposing. His offer was accepted immediately, and there was no mention of the conventional waiting period before remarrying after widowhood.[66][67] Although Mr. Sneyd was opposed to his daughter's marriage,[68] the couple were married at Lichfield Cathedral on 17 July 1773, officiated by Canon Thomas Seward, Anna Seward being a bridesmaid.[69][70] After marrying, problems with the Edgeworth family estates in Ireland required the couple to immediately move to Edgeworthstown, County Longford in Ireland.[66][70][16]

Through this marriage Sneyd became step-mother to Edgeworth's four surviving children by his first wife, Anna Maria, ranging from seven months to nine years in age; Richard, Maria, who became a writer in her own right, Emmeline and Anna Maria.[71][72] On encountering her new family she observed that Maria, then aged five, was exhibiting behavioural problems, and expressed her views that speedy and consistent punishment were the keys to ensuring good behaviour in children, a view she proceeded to practice. However, she believed that such discipline needed to be imposed "before the age of 5 or 6", and was therefore rather late in the case of the older children;[66] however, she imposed a strict discipline.[73] Following a period of ill health on Sneyd's part,[74] Maria Edgeworth was sent away to boarding school in Derby (1775–1781), and later London upon the death of Honora Sneyd (1781–1782).[75][76][77] Similarly, her older brother Richard was sent to Charterhouse (1776–1778) and then went to sea, and she never saw him again.[78] Later Richard Edgeworth would comment on how difficult the first two years were for Sneyd in her new role as stepmother to undisciplined children, a role her relatives had advised her against.[79][80][81]

Honora Sneyd was soon pregnant, giving birth to her daughter Honora on 30 May 1774, who died at the age of sixteen.[62] Her second child, Lovell, who inherited the property, was born the following year on 30 June 1775.[i] The Edgeworth children were raised according to the system of Rousseau, as refined and modified by the Edgeworths.[82] Richard Edgeworth considered his early educational efforts a failure, the older children from his first marriage growing up unruly and then being sent away to school, and readily concurred with his new wife's stricter rules.[73] However, he had seen very little of them in their early years.[81]

Return to England 1776–1780 edit

After three years in Ireland, in 1776[j] they moved to England again, taking up residence in Northchurch,[k]Hertfordshire[88] Despite Anna Seward's despair at the loss of her friend, she and Honora had maintained regular correspondence and visits. However, these suddenly ceased, an event that Anna blamed Honora Sneyd's father for.[89] During a temporary absence of Edgeworth on business in Ireland in the spring of 1779, Honora Sneyd fell ill with a fever,[90] just as he was summoning her to let the house and join him there.[91] On his return they consulted Erasmus Darwin at Lichfield, who was of the opinion the illness was more severe than at first thought, being a recurrence of consumption (T.B.) from which she had had a brief bout at the age of fifteen.[92] He advised against returning to Ireland but rather, moving closer to Lichfield. For a while they stayed at the Sneyd house that was temporarily vacant while consulting a wide range of physicians including William Heberden (Samuel Johnson's physician), and even staying with Day near London to be close to medical care. but only received news of incurability.[90] Eventually they rented Bighterton,[l] near Shifnal, Shropshire, closer to the Sneyds, Darwin and others of their circle,[94] where Honora Sneyd drew up her will in April.[95]

Death edit

Four years after returning to England Honora Sneyd died of consumption at six in the morning[95] on 1 May 1780[m] at Bighterton, surrounded by her husband, her youngest sister, Charlotte and a servant.[96] Honora Sneyd was buried in the nearby Weston church where a plaque on the wall (see box) bears witness to her life.[n][98] Honora Sneyd died within eight years of her marriage to Richard Edgeworth, at almost the same age as her predecessor. The same disease which had taken the life of her mother and five maternal aunts[90] would soon claim the life of her young daughter, Honora Edgeworth (1790),[99] as well as her younger sister, Elizabeth, seven years later (1797), as well as at least two of Elizabeth's children, Charlotte (1807) and Henry (1813). Honora's brother, Lovell was also affected by the consumption.[100] At the time it was thought this was a hereditary weakness carried by the family.[74]

On Honora Sneyd's death, Edgeworth married her younger sister, Elizabeth Sneyd, stating that this had been the dying wish of Honora.[96] Uglow speculates that this was a marriage of convenience, for the sake of the children.[101] Although it was technically legal to marry one's wife's sister, the marriage was considered scandalous, and was opposed by the Sneyds, Sewards and Edgeworths as well as the Bishop.[102] The couple fled to London where they were married on Christmas Day with Thomas Day as witness, before proceeding to live at Northchurch.[63][102] The scandal may have given rise to less charitable interpretations of Edgeworth's actions, although there is no direct evidence to support or refute these.[103][104][105] Honora Sneyd's will, drawn up during the last month of her life refers only to "that Woman whom he shall think worthy to call his, for her to wear, so long as they both shall LOVE", referring to a cameo she owned of Richard Edgeworth.[95]

Work edit

Practical education edit

The Edgeworths jointly developed the concept of "Practical Education", a principle that would become a new paradigm by the 1820s.[106] Having determined that after eight years, Richard Edgeworth's attempt to raise his eldest son Richard according to the principles of Rousseau was a failure,[107] he and Honora were determined to find better methods. After the birth of Honora's first child (1774),[o] the Edgeworths embarked on a plan, partly inspired by Anna Barbauld, to write a series of books for children.[110][111] After trying many other methods, Barbauld's Lessons for Children from two to three years old was published in 1778, and the Edgeworths used it on Anna (5) and Honora (4), and were delighted to find that the girls learned to read in six weeks.[112] Now back in England, at Northchurch the Edgeworths were in closer contact with the intellectuals of the Lunar society.[113] Richard Edgeworth and Honora were determined to design a plan for the education of their children. They started by reviewing the existing literature on childhood education (including Locke, Hartley, Priestley in addition to Rousseau), and then proceeded to document their observations of the behaviour of children and then developed their own "practical" system. To this end Erasmus Darwin suggested they start by reading the work of Dugald Stewart. Honora Sneyd then started recording extensive notes on her observations of the Edgeworth children. These then became the dialogues in the final book.[111]

Richard and Maria Edgeworth state that "She [Honora] was of opinion that the art of education should be considered as an experimental science",[114] and that the failures of the past were due to "following theory rather than practice". Richard Edgeworth and Honora then set about applying the emerging principles of educational psychology to the actual practice of education. From their reading of theory they determined that the reason Barbauld was successful was that the child's reading was rewarded (thus departing radically from Rousseau),[106] because it was associated with pleasure.[115] Honora Sneyd conceived of the title of their work therefore as Practical Education.[116][107] With her husband, Honora wrote the first version of Practical Education as a children's book Practical education: or, the history of Harry and Lucy for Honora her daughter, which was begun in 1778 and privately published in February 1780 in Lichfield as Practical Education, vol 2.[117][63] The book tells a simple story of two parents and their two model children, Harry and Lucy, who carry out domestic chores and ask their parents many questions, the answers to which may be deemed educational. The children explain their discoveries and how they learn, the whole presented as nine forms of learning. As originally conceived it was intended to be the second part of a series of three books, but the remaining parts remained unwritten. The original plan had been for a collaborative work, contributed to by various members of the Lunar Society.[118] it was an ambitious project designed to fill what they perceived of as major deficiencies in the field of both technical and scientific education and to introduce early ideas on morality, science and other academic disciplines into the developing mind of the young child.[119] After Honora Sneyd's premature death, her sister Elizabeth continued the work,[120] in her role as the third wife of Richard Edgeworth.[121] The final version of the book was authored by Richard and Maria Edgeworth and published after both Honora and her sister Elizabeth's deaths, in 1798, and further revised under Maria's name as Early lessons (1801–1825).[122] In reality this was a family project contributed to by a number of their members that would extend over 50 years, beyond Richard Edgeworth's death in 1817 (c. 1774–1825).[p][111][124][125]

Richard Edgeworth observed on his wife's death that being familiar with the experimental method in science, she was surprised to find that educational theory was based on very little empirical evidence, and set out to apply experimental science to child education and devised, executed and recorded experiments with children.[120][16][111] She conceived and executed a register (2 volumes 1778–1779)[126][83] of the reaction of children to new knowledge and experience,[119] given her interest in applying experimental science to the field of child education. She observed the questions that children asked, what they did, and how they solved problems. An extensive example of her recorded dialogue is given by Richard and Maria Edgeworth in "Practical Education".[127] This formed the basis of Richard Edgeworth's Essays on professional education (1809). In the Bodleian Library there is a short story in manuscript dated 1787 and other fragments attributed to Honora Sneyd.[q][16][83] Her parents' principles of childhood education were to be a profound influence on Maria Edgeworth's own career as a writer for children.[118]

Other edit

Honora Sneyd, through her early contact with members of the Lunar Society, had always taken a keen interest in science, an attribute that drew the intention of Richard Edgeworth who considered himself an inventor.[128] Following their marriage, she worked on his projects with him and in his words, "became an excellent theoretic mechanick"[129] herself.[130]

Legacy edit

Since little of Honora Sneyd's own words have survived, our image of her is largely through the eyes of others, in particular Anna Seward and Richard Edgeworth. Honora Sneyd is often listed amongst the members or associates of the Bluestockings, educated upper class literary women who disdained traditional female accomplishments and often formed close female friendships.[131] The depiction of the effect of consumption on her has been used as a symbol of the pervasiveness of the disease in eighteenth-century culture.[132][133] The work she started on educational psychology would prove to be immensely influential throughout the nineteenth century.[134] Her name is also inextricably entwined with that of Anna Seward in the literature of lesbian relationships and female friendship.[36][135][136]

From growing up in the Seward household with Canon Seward and the members of the Lunar Society, Honora Sneyd and her childhood friend Anna Seward developed relatively progressive views for the times on the status of women and equality in marriage, a key to which was female education. Sneyd entered into marriage with Richard Edgeworth on the understanding that they were equal partners in his work.[129] Anna,[137] and later Honora's stepdaughter, Maria Edgeworth,[138] were to take those values and promote them in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Britain, the ancestors of modern feminists.[139] Today Honora's position on women's rights is best remembered for her rebuke of Thomas Day and his theory of the "perfect wife".[49][140]

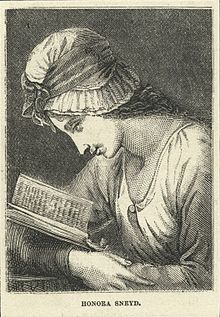

Anna Seward's will mentions two likenesses of Honora Sneyd in her possession that she wished to bequeath. The first of these was a mezzotinto engraving after George Romney,[1][2][3] which she had modeled for as "Serena"[4] (see Figure, above) to Honora's brother Edward. The other was a drawn miniature portrait by John André (1776) which she left to her cousin and confidante[141] Mary Powys.[142][57] A jasper medallion, after an image by John Flaxman,[143] was issued by the Wedgwood factory in 1780 (right).[144][145] Honora Sneyd was the subject of many of Seward's poems,[34] When Sneyd married Edgeworth, she became the subject of Seward's anger, yet the latter continued to write about Sneyd and her affection for her long after her death.[146] In addition to being immortalised in Anna Seward's poetry, Sneyd appears semi-fictionalised as a character in a play about Major André and herself, André; a Tragedy in Five Acts by William Dunlap, first produced in New York in 1798.[147]

The plaque in St. Andrew's Church, Weston, where she is buried, on the north wall of the tower, reads;[98]

MDCCLXXX

Near this place was buried

HONORA EDGEWORTH,

aged 28 years.

Her Manners, Wisdom, and Virtue,

gained Admiration and Esteem,

without exciting

Envy.

Appendix: Persons mentioned edit

- Parents

- Edward Sneyd (1711–1795) m. 1742 Susanna Cook d. 1757, by whom;

- Elizabeth Sneyd (1753–1797)

- Charlotte Sneyd d. 1822

- Edward Sneyd (1711–1795) m. 1742 Susanna Cook d. 1757, by whom;

- Foster family

- Thomas Seward (1708–1790) m. 1741 Elizabeth Hunter d. 1780, by whom;

- Anna Seward (1742–1809)

- Sarah Seward (1744–1764)

- Thomas Seward (1708–1790) m. 1741 Elizabeth Hunter d. 1780, by whom;

- Extended family

- Henry Powys d. 1774 m. Susannah Sneyd (1729–1791), by whom

- Mary Powys d. 1829

- Henry Powys d. 1774 m. Susannah Sneyd (1729–1791), by whom

- Literary acquaintances

- David Garrick (1717–1779)

- Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802)

- Samuel Johnson (1709–1784)

- James Boswell (1740–1795)

- Suitors

- John André (1751–1780)

- Thomas Day (1748–1789)

- Husband and children

- Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744–1817)

- m. 1763 (1) Anna Maria Elers (1743–1773), by whom;

- Richard Edgeworth (1765–1796)

- Lovell Edgeworth (1766–1766)

- Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849)

- Emmeline Edgeworth (1770–1817)

- Anna Maria Edgeworth (1773–1824)

- m. 1773 (2) Honora Sneyd (1751–1780), by whom

- Honora Edgeworth (1774–1790)

- Lovell Edgeworth (1775–1842)

- Influences

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)

- Anna Barbauld (1743–1825)

- John Locke (1632–1704)

- David Hartley (1705–1757)

- Joseph Priestley (1733–1804)

- Dugald Stewart (1753–1828)

- Artists

- John Flaxman (1755–1826)

- James Hopwood (c. 1740–1819)

- George Romney (1734–1802)

- Other

- William Dunlap (1766–1839)

- William Heberden (1710–1801)

Notes edit

- ^ Adam Buck (Irish, 1759–1833) Portrait of Miss Charlotte Sneyd; Portrait of Miss Mary Sneyd Watercolour, a pair, 21.5 x 16.5 cm, (8.5 x 6.5 in) each Bears inscriptions "Charlotte Sneyd 1790 by Mr Buck" and "Mary Sneyd 1790 by Mr Buck" on reverse

- ^ Some sources spell her name 'Honoria';[10] however, she styled herself Honora Sneyd Edgeworth in her publications

- ^ Intermarriage between families was relatively common at the time. Daughters of the Rev Moses Cook, Susanna's elder sister Mary had married Edward Sneyd's older brother Ralph in 1724

- ^ Ah, dear HONORA! that remember'd day, First on these eyes when shone thy early ray (p. 69)

- ^ "and being canon of this cathedral, his daughter necessarily converses on terms of equality with the proudest inhabitants of our little city"[31]

- ^ The Edgeworths pointed out an error in the poem that suggested that André enlisted in reaction to news of Honora's marriage. In fact he enlisted two years earlier in 1771.[44]

- ^ Ralph Sneyd (d. 1729) of Bishton, Staffordshire m. Elizabeth Bowyer, and by her had six sons and five daughters. Of those, his eldest son and heir William Sneyd, m. 1724 Susanna Edmonds, and by her had two sons and four daughters. The youngest daughter, Susanna Sneyd m. Henry Powys of Shropshire, and they fostered Elizabeth Sneyd from 1756 to 1771, Honora Sneyd's younger sister. The fifth son of William Sneyd was Major Edward Sneyd of Lichfield, Honora Sneyd's father. Thus Susanna Sneyd (Mrs. Henry Powys) was the niece of Major Edward Sneyd.[56] The Powyses had a daughter, Mary, who was a close confidante of Anna Seward, cousin to Honora Sneyd, and godmother to Honora Sneyd's daughter, Honora Edgeworth.[57]

- ^ Anna Maria Edgeworth's birthdate is placed here as March 1773, the same month as her mother's death[63][64] not 1772 as other sources state[65]

- ^ Some sources state 1776, but he was born in Ireland and the family moved back to England before the end of that year

- ^ Some sources state 1777, but there appears to be evidence of occupation of the Northchurch home at least by the end of 1776 [83][84][85]

- ^ The house at 20 High Street was originally named The Limes but was renamed Edgeworth House in 1911.[86] Maria Edgeworth would spend her school holidays there while her father remained in England (1776–1781)[87][85]

- ^ A 19th-century history of Staffordshire locates this as a farm house in Weston-under-Lizard, just across the county border in Staffordshire, also spelt Beighterton[93]

- ^ Many sources give the date of death as 30 April, but the Edgeworths state she died the following morning

- ^ The Edgeworths give the place of burial as King's Weston, near Bristol. This appears to be an error, given the evidence from the parish of Weston (Shropshire) itself. Furthermore Anna Seward gives an account of a visit to the grave in the following year in Lichfield, an Elegy (May 1781), to which Scott adds a note that this is the 'Weston, on the edge of Shropshire'.[97] Richard Edgeworth had not completed his memoirs at the time of his death in 1817, thirty seven years later, and they were completed by Maria Edgeworth in 1821. Maria was only 12 when her step mother died.

- ^ Once source attributes to Maria the statement that the date of the start of this project was 1778, but this seems rather late. The oldest step child (Richard) would have been fourteen by then and her own daughter Honora four, but also this was only two years before her death,[108] Butler dates this to 1777.[109]

- ^ Honora Edgeworth's contributions are discussed in the Preface to Volume I[123] and the Appendix to Volume II[44]

- ^ The authorship of these publications is complex, as outlined by Myers.[111] Honora Sneyd wrote two short stories entitled Practical Education that were published after her premature death, in 1780. Maria Edgeworth then revised and republished these Harry and Lucy stories as part of Early Lessons (1801)[122]

References edit

- ^ a b Hopwood 1811a.

- ^ a b Hopwood 1811b.

- ^ a b Romney 2015.

- ^ a b Chamberlain 1910, Appendix II. Honora Sneyd and the 'Serena' pictures pp.386–389.

- ^ Adam's 2015, Portraits of Charlotte and Mary Sneyd, 1790.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821b, p. 372.

- ^ a b MacDonald 1977, p. 273.

- ^ Burke 1871, ii: p. 1288.

- ^ King-Hele 2007, p. 527.

- ^ Fraser's 1832.

- ^ Lundy 2015, Edward Sneyd.

- ^ Gentleman's Magazine 1795, Obituaries p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Butler 1972, p. 41.

- ^ Bensusan Butt 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Bowerbank 2015.

- ^ a b c d Loeber et al. 2015.

- ^ a b c d Barnard 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Martin 1909.

- ^ Backscheider 2005, p. 297.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 232.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 5.

- ^ Scott 1810, The Anniversary, vol. I p. 68.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 29.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 234.

- ^ a b Scott 1810, The Visions, vol. I p. 1.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 37.

- ^ a b Scott 1810, p .cxvii.

- ^ Dodsley 1765, Seward, T. The Female Right to Literature Volume 2, pp. 309–315.

- ^ a b Uglow 2002a, pp. 322–324.

- ^ a b Barnard 2013, p. 33.

- ^ Scott 1810, Letter February 1763. vol. I p. lxxiii.

- ^ a b Barnard 2004.

- ^ Kairoff 2012, p. x.

- ^ a b deLucia 2013.

- ^ Faderman 1981.

- ^ a b Barrett 2012.

- ^ Seward 1804, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 235.

- ^ Barnard 2013, pp. 36, 77.

- ^ Lawless 1904.

- ^ Cawley 2015.

- ^ Scott 1810, Monody on Major André, vol. II p. 68.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 236.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1801, Appendix p. 301.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 237.

- ^ Blackman 1862, p. 62.

- ^ Fraser's 1832, p. 556.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 244.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 245.

- ^ North 2007.

- ^ Powys-Lybbe 2011, Susannah Sneyd.

- ^ Owen 1825, p. 136.

- ^ Oliver 1882, p. 48.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 244–245.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 246.

- ^ Burke & Burke 1847, Sneyd of Ashcombe p .1261.

- ^ a b Colvin 1971, p. 640.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 330.

- ^ a b Butler 1972, p. 42.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 45.

- ^ Lundy 2015, Anna Maria Elers.

- ^ a b Barbé 2010, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Colvin 2015.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 318.

- ^ Lundy 2015, Richard Lovell Edgeworth.

- ^ a b c Butler 1972, p. 46.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 316.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Uglow 2002a, p. 329.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 321.

- ^ MacDonald 1977.

- ^ Uglow 2002a, pp. 386.

- ^ a b Butler 1972, p. 50.

- ^ a b Zimmern 1884.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 71.

- ^ Gonzalez 2006, Claire Denelle Cowart: Maria Edgeworth. p. 109 .

- ^ Cone & Gilder 1887, Maria Edgeworth p. 161.

- ^ Butler 1972, p .51.

- ^ Butler 1972, pp. 48, 51.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 348.

- ^ a b Manley 2012.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Bodleian 1993.

- ^ Barbé 2010, p. 4.

- ^ a b ADS 2015, Extensive Urban Survey. Berkhamsted 2005.

- ^ British Listed Buildings 2015, Edgeworth House, Berkhamsted.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 55.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 329.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Butler 1972, p. 67.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 356.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 358.

- ^ Collections for a history of Staffordshire 1899, p. 278.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 361.

- ^ a b c Butler 1972, p. 68.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 364.

- ^ Scott 1810, Lichfield, an Elegy May 1781, vol. I p. 89.

- ^ a b Collections for a history of Staffordshire 1899, p. 325.

- ^ Maria Edgeworth 2013, p. 5713.

- ^ Weber 2007, Brian Hollingworth: Richard Edgeworth as parent and educator. p. 29.

- ^ Uglow 2002a, pp. 547.

- ^ a b Butler 1972, p. 70.

- ^ Genet 1991, Maria Edgeworth: Castle Rackrent. p. 67.

- ^ Russell 1875, p. 194.

- ^ McCormack 2015.

- ^ a b Oelkers 2015, The Concept of Child before Progressive Education.

- ^ a b O'Connor 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Hall 1849.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 58.

- ^ Uglow 2002a, p. 543.

- ^ a b c d e Myers 1999.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 61.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 60.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1801, Appendix. p. 301.

- ^ Butler 1972, p. 62.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1801, Appendix pp. 301–302.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1780.

- ^ a b Butler 1972, p. 63.

- ^ a b Butler 1972, p. 64.

- ^ a b Butler 1972, p. 65.

- ^ Narain 2006, p. 59.

- ^ a b Edgeworth 1801.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1811, Preface p. x.

- ^ Fraser's 1832, pp. 557–8.

- ^ Edgeworth 1820, p. 1216.

- ^ Edgeworth-Butler 1972.

- ^ Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1811, p. 75.

- ^ Uglow 2002a, p. 323.

- ^ a b Edgeworth & Edgeworth 1821a, p. 347.

- ^ Uglow 2002a, p. 386.

- ^ Bluestocking 2013.

- ^ Lawlor & Suzuki 2000.

- ^ Lawlor 2007.

- ^ O'Donnell 2009.

- ^ Kauth 2012.

- ^ Backscheider 2005.

- ^ Kairoff 2012.

- ^ Narain 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Stafford 2002.

- ^ Moore 2013.

- ^ Barnard 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Lady's Monthly 1812, Miss Seward's Will Wednesday 1 April 1812 pp. 190–195.

- ^ Flaxman 1780.

- ^ Meteyard 1875, Portrait Medallions. Modern. p. 189.

- ^ Wedgwood 1780.

- ^ Faderman 1981, pp. 132–136.

- ^ Dunlap 1798.

Bibliography edit

Books and articles edit

- Backscheider, Paula R., ed. (2002). Revising women: eighteenth-century "women's fiction" and social engagement. Baltimore, MD, USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801870958. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Backscheider, Paula R. (2005). Eighteenth-century women poets and their poetry inventing agency, inventing genre (PDF). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801895906. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Bensusan Butt, John (2009). D'Cruze, Shani (ed.). Essex in the age of enlightenment : essays in historical biography (2nd ed.). U.K.: Lulu.com. ISBN 9781445210544.

- Chamberlain, Arthur Bensley (1910). George Romney. London: Methuen. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Faderman, Lillian (1981). Surpassing the love of men: romantic friendship and love between women from the Renaissance to the present. London: Women's Press. ISBN 9780704339774.

- Genet, Jacqueline, ed. (1991). The big house in Ireland : reality and representation. Dingle, Co. Kerry: Brandon. ISBN 9780389209683. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Gonzalez, Alexander G., ed. (2006). Irish women writers : an A-to-Z guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313328831.

- Gottlieb, Evan; Shields, Juliet, eds. (2013). Representing place in British literature and culture, 1660–1830 : from local to global. Farnham. ISBN 9781409419303.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)- DeLucia, JoEllen. Mundy's Needwood Forest and Anna Seward's Lichfield Poems. pp. 155–172. In Gottlieb & Shields (2013)

- Kauth, Michael R (2012). True nature : a theory of sexual attraction. Perspectives in Sexuality. New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4301-5. ISBN 978-1-4613-6930-1.

- Lawlor, Clark; Suzuki, Akihito (2000). "The disease of the self: representing consumption, 1700-1830". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 74 (3): 458–494. doi:10.1353/bhm.2000.0130. PMID 11016095. S2CID 44657588. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Lawlor, Clark (2007). Consumption and literature : the making of the romantic disease. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230020030.

- Meteyard, Eliza (1875). The Wedgwood Handbook: A Manual for Collectors. Treating of the Marks, Monograms, and Other Tests of the Old Period of Manufacture. Also Including the Catalogues, with Prices Obtained at Various Sales, Together with a Glossary of Terms. London: George Bell and Sons. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Money, John (1977). Experience and Identity: Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1760–1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780773593428.

- Moore, Wendy (2013). How to create the perfect wife: Britain's most ineligible bachelor and his enlightened quest to train the ideal mate. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465065738.

- O'Donnell, Katherine (2009). "Castle Stopgap : historical reality, literary realism, and oral culture" (PDF). Eighteenth Century Fiction. 22 (1): 115–130. doi:10.3138/ecf.22.1.115. hdl:10197/2040. S2CID 162629638.

- Stafford, William (2002). English feminists and their opponents in the 1790s : unsex'd and proper females. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719060823.

- Uglow, Jenny (2002a). The lunar men: five friends whose curiosity changed the world. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 9780374194406.

- —— (5 October 2002). "Educating Sabrina". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

Web sites edit

- Adam's (2015). "Home". Adam's Auctioneers of Dublin. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Edgeworthstown House, Co. Longford". Ask About Ireland. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- British Listed Buildings. "British Listed Buildings Online". Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "Archaeology Data Service". University of York. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "Reinventing the feminine: Bluestocking women writers in 18th century London". 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "National Portrait Gallery". 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Victoria and Albert Museum". 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Dunlap, William (1798). "André; a Tragedy in Five Acts". New York: T & J Swords. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

Educational theory and practice edit

- Curtis, Stanley James; Boultwood, Myrtle E. A. (1977). A short history of educational ideas (5th ed.). University Tutorial Press. ISBN 9780723107675.

- Friedman, Jean E. (2001). Ways of wisdom : moral education in the early national period. Athens, Ga.: Univ. of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820322520. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- O'Connor, Maura (2010). The Development of Infant Education in Ireland, 1838–1948: Epochs and Eras. Bern: Lang. ISBN 9783034301428. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Oelkers, Jürgen. "English lectures". Institut für Erziehungswissenschaft: University of Zurich. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Weber, Carolyn A., ed. (2007). Romanticism and parenting image, instruction and ideology. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Pub. ISBN 9781443809177. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

Anna Seward edit

- Barnard, Teresa (2004). "Anna Seward and the Battle for Authorship". Corvey Women Writers on the Web 1796–1834 (1 Summer). Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- —— (2013). Anna Seward: A Constructed Life: A Critical Biography. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 9781409475330. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Barrett, Redfern Jon (2012). ""My Stand": Queer Identities in the Poetry of Anna Seward and Thomas Gray". Gender Forum (39). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Kairoff, Claudia Thomas (2012). Anna Seward and the end of the eighteenth century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421403281. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Martin, Stapleton (1909). Anna Seward and Classic Lichfield. Deighton and Co. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- North, Alix (2007). "Anna Seward 1747–1809". Isle of Lesbos. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Scott, Walter, ed. (1810). The Poetical Works of Anna Seward with Extracts from her Literary Correspondence (3 vols.). Edinburgh: James Ballantyne.

- Volume 1

- Volume 2

The Edgeworths edit

- Barbé, Lluís (2010), Francis Ysidro Edgeworth: A Portrait With Family and Friends, Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 9781849803229

- Clarke, Desmond (1965). The ingenious Mr. Edgeworth. Oldbourne. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Manly, Susan (14 March 2014). "Highlights from the Reading Room: Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth". Echoes from the Vault. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

Honora edit

- Loeber, Rolf; Loeber, Magda; Burnham, Anne Mullin. "Honora Edgeworth". A Guide to Irish Fiction 1650 – 1900. National University of Ireland. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Hopwood, James (1811). "Miss Sneyd. Engraved by Hopwood from a painting by Romney" (Image). British portrait prints. National Library of Ireland. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Hopwood, James (1811). "Serena Reading (called Honora Edgeworth (née Sneyd))" (Stipple engraving after George Romney). Retrieved 19 March 2015. In NPG (2015)

- Flaxman, John (1780). "Honora Sneyd Edgeworth" (Jasperware). Retrieved 19 March 2015. In VAM (2015)

- Wedgwood (1780). "Honora Sneyd Edgeworth" (Jasper medallion). Retrieved 19 March 2015. In VAM (2015)

Maria edit

- Cornhill Magazine (11 November 1882). "Miss Edgeworth". The Living Age. 155 (2003): 323–337. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Cornhill Magazine (9 December 1882). "Miss Edgeworth". The Living Age. 155 (2007): 595–608. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Butler, Marilyn (1972). Maria Edgeworth: A Literary Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198120179. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Colvin, Christina, ed. (1971). Maria Edgeworth: Letters from England, 1813-1844. Clarendon Press.

- Lawless, Emily (1904). Maria Edgeworth. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- MacDonald, Edgar E. (1977). The Education of the Heart: The Correspondence of Rachel Mordecai Lazarus and Maria Edgeworth. UNC Press. ISBN 9781469606095.

- Manley, Susan (2012). "Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849)" (PDF). Biographies of Women Writers. Chawton House Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Myers, Mitzi (Winter 1999). "'Anecdotes from the Nursery" in Maria Edgeworth's Practical Education (1798): Learning from Children 'Abroad and at Home'" (PDF). Princeton University Library Chronicle. 60 (2): 220–250. doi:10.25290/prinunivlibrchro.60.2.0220. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Nash, Julie, ed. (2006). New essays on Maria Edgeworth. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754651758.

- Narain, Mona (2006). Not the Angel in the House. pp. 57–72., In Nash (2006)

- "George Romney" (Serena Reading, by George Romney. Model: Honora Sneyd). The Romney Society. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Cawley, Bill (14 February 2015). "Honora Sneyd and Major Andre'- A story for Valentines Day". Moorlands Old Times. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Oliver, Grace Atkinson (1882). A Study of Maria Edgeworth: With Notices of Her Father and Friends (2nd. ed.). Boston: A. Williams and Company. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Zimmern, Helen (1884). Maria Edgeworth. Boston: Roberts. ISBN 9781465520937. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

Works by the Edgeworths edit

- Edgeworth, Honora Sneyd; Edgeworth, Richard Lovell (1780). Practical Education; or, The History of Harry and Lucy, vol. 2. Lichfield: J. Jackson.

- Edgeworth, Richard Lovell; Edgeworth, Maria (1821a). The Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: Hunter, Cradock & Joy.

- ——; —— (1821b). The Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). London: Hunter, Cradock & Joy. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Review: Lady's Monthly Museum 1820 p. 326

- Edgeworth, Maria (2013). Complete Novels of Maria Edgeworth (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Edgeworth, Maria (1801). Early Lessons (1st ed.). London: Johnson. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Edgeworth, Maria (1820). "RL Edgeworth Esq". The Annual Register. Part II: 1215–1223.

- ——; Edgeworth, Richard (1811) [1798]. Essays on Practical Education. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). London: Johnson.

- ——; —— (1801) [1798]. Essays on Practical Education. Vol. 2 (American ed.). Washington's Head: Hopkins.

Historical sources edit

- Russell, W Clark (August 1875). Bidwell, W H (ed.). "Follies of the Wise". The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art. New Series. 22 (2): 186–196. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Blackman, John (1862). A Memoir of the Life and Writings of Thomas Day, author of "Sandford and Merton.". London: Leno.

- Cone, Helen Gray; Gilder, Jeanette L, eds. (1887). Pen-portraits of Literary Women. New York: Cassell. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Dodsley, Robert, ed. (1765) [1748]. A collection of Poems in six volumes by Several Hands. London: Dodsley. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- Froude, James Anthony; Tulloch, John (1832). "Miss Edgeworlh's Tales and Novels". Fraser's Magazine. 6 (November): 541–558. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Hall, S. C. (1849). "Edgeworthstown: Memories of Maria Edgeworth". Living Age. 22: 320–329. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- King-Hele, Desmond, ed. (2007). The collected letters of Erasmus Darwin. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 9780521821568. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Lovett, Richard (1888). Irish pictures drawn with pen and pencil. London: The Religious Tract Society. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Edgeworthstown

- Owen, Hugh (1825). A history of Shrewsbury. London: Harding, Lepard, and Co. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Seward, Anna (1804). Memoirs of the Life of Dr. Darwin: Chiefly During His Residence in Lichfield: With Anecdotes of His Friends, and Criticisms on His Writing. Philadelphia: W.M. Poyntell. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- The William Salt Archaeological Society, ed. (1899). Collections for a history of Staffordshire Volume XX New Series Volume II History of the Manor and Parish of Weston-under-Lizard, in the County of Stafford. London: Harrison and Sons. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 65 Part I, 1795

- A Society of Ladies, ed. (1812). "Polite Repository of Amusement and Instruction". The Lady's Monthly Museum. New Series. 12. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

Reference materials edit

- Bowerbank, S. "Seward, Anna (1742–1809)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25135. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Colvin, Christina Edgeworth. "Edgeworth, Richard Lovell (1744–1817)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8478. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McCormack, W. J. "Edgeworth, Maria (1768–1849), novelist and educationist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8476. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Encyclopædia Britannica vol. VII (Ninth (American) ed.). Philadelphia: Maxwell Summerville. 1891.

- Priestman, Judith; Clapinson, Mary; Rogers, Tim (1993). "Catalogue of the papers of Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849), and the Edgeworth family, 17th–19th century". University of Oxford, Bodleian Library. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Edgeworth Papers. Collection List 40" (PDF). National Library of Ireland. p. 112. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Edgeworth Collection (Longford County Library)". Ask About Ireland. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- (Edgeworth) Butler Papers (Private collection), see Butler (1972) Bibliography p. 501

Genealogy edit

- Burke, John; Burke, John Bernard (1847). Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry 2 vols. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Burke, Bernard (1871). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland 2 vols. London: Harrison. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Lundy, Darryl (2015). "Home". The Peerage: A genealogical survey of the peerage of Britain as well as the royal families of Europe.

- Powys-Lybbe, Tim (2011). "Powys-Lybbe forbears". Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "The Four Wives of Richard Lovell Edgeworth & The Children of Richard Lovell Edgeworth" (Images). English-Irish Edgeworths. House of Edgeworth, South Carolina. Retrieved 24 March 2015.