Summary

Hydroxyzine, sold under the brand names Atarax and Vistaril among others, is an antihistamine medication.[8] It is used in the treatment of itchiness, insomnia, anxiety, and nausea, including that due to motion sickness.[8] It is used either by mouth or injection into a muscle.[8]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /haɪˈdrɒksɪziːn/ |

| Trade names | Atarax,[1] Vistaril,[2] others |

| Other names | UCB-4492 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682866 |

| License data |

|

| Dependence liability | None [3] |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Drug class | First generation antihistamine[4] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High |

| Protein binding | 93% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Metabolites | Cetirizine, others |

| Elimination half-life | Adults: 20.0 hours[5][6] Elderly: 29.3 hours[7] Children: 7.1 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Urine, feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID |

|

| IUPHAR/BPS |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.630 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H27ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 374.91 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

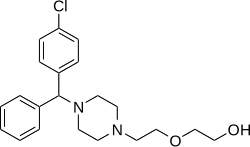

Common side effects include sleepiness, headache, and a dry mouth.[8][9] Serious side effects may include QT prolongation.[9] It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[8] Hydroxyzine works by blocking the effects of histamine.[9] It is a first-generation antihistamine in the piperazine family of chemicals.[8][4]

It was first made by Union Chimique Belge in 1956 and was approved for sale by Pfizer in the United States later that year.[8][10] In 2021, it was the 58th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 11 million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical uses edit

Hydroxyzine is used in the treatment of itchiness, anxiety, and nausea due to motion sickness.[8]

A systematic review concluded that hydroxyzine outperforms placebo in treating generalized anxiety disorder. Insufficient data were available to compare the drug with benzodiazepines and buspirone.[13]

Hydroxyzine can also be used for the treatment of allergic conditions, such as chronic urticaria, atopic or contact dermatoses, and histamine-mediated pruritus.[medical citation needed] These have also been confirmed in both recent and past studies to have no adverse effects on the liver, blood, nervous system, or urinary tract.[14][better source needed]

Use of hydroxyzine for premedication as a sedative has no effects on tropane alkaloids, such as atropine, but may, following general anesthesia, potentiate meperidine and barbiturates, and use in pre-anesthetic adjunctive therapy should be modified depending upon the state of the individual.[14]

Doses of hydroxyzine hydrochloride used for sleep range from 25 to 100 mg.[15][16][17] As with other antihistamine sleep aids, hydroxyzine is usually only prescribed for short term or "as-needed" use since tolerance to the CNS (central nervous system) effects of hydroxyzine can develop in as little as a few days.[18][non-primary source needed] A major systematic review and network meta-analysis of medications for the treatment of insomnia published in 2022 found little evidence to inform the use of hydroxyzine for insomnia.[19] A 2023 meta-review concludes that hydroxyzine is effective for inducing sleep onset but less effective for maintaining sleep for eight hours.[20]

Gabasync edit

Gabasync, a treatment consisting of a combination of hydroxyzine and two other medications (gabapentin and flumazenil) as well as therapy, is an ineffective treatment promoted for methamphetamine addiction, though it had also been claimed to be effective for dependence on alcohol or cocaine.[21] It was marketed as PROMETA. While the individual drugs had been approved by the FDA, their off-label use for addiction treatment has not.[22] Gabasync was marketed by Hythiam, Inc. which is owned by Terren Peizer, a former bond salesman who has since been indicted for securities fraud relative to another company.[23][24] Hythiam charges up to $15,000 per patient to license its use (of which half goes to the prescribing physician, and half to Hythiam).[25]

In November 2011, the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (financed by Hythiam and carried out at UCLA) were published in the peer-reviewed journal Addiction. It concluded that Gabasync is ineffective: "The PROMETA protocol, consisting of flumazenil, gabapentin and hydroxyzine, appears to be no more effective than placebo in reducing methamphetamine use, retaining patients in treatment or reducing methamphetamine craving."[26]

Contraindications edit

Hydroxyzine is contraindicated for subcutaneous or intra-articular administration.[27][28]

The administration of hydroxyzine in large amounts by ingestion or intramuscular administration during the onset of pregnancy can cause fetal abnormalities. When administered to pregnant rats, mice and rabbits, hydroxyzine caused abnormalities such as hypogonadism with doses significantly above that of the human therapeutic range.[29][better source needed]

In humans, a significant dose has not yet been established in studies and, by default, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has introduced contraindication guidelines in regard to hydroxyzine.[29] Use by those at risk for or showing previous signs of hypersensitivity is also contraindicated.[29]

Other contraindications include the administration of hydroxyzine alongside depressants and other compounds which affect the central nervous system;[29] if absolutely necessary, it should only be administered concomitantly in small doses.[29] If administered in small doses with other substances, as mentioned, then patients should refrain from using dangerous machinery, motor vehicles or any other practice requiring absolute concentration, in accordance with safety laws.[29]

Studies have also been conducted which show that long-term prescription of hydroxyzine can lead to tardive dyskinesia after years of use, but effects related to dyskinesia have also anecdotally been reported after periods of 7.5 months,[30] such as continual head rolling, lip licking and other forms of athetoid movement. In certain cases, elderly patients' previous interactions with phenothiazine derivatives or pre-existing neuroleptic treatment may have contributed to dyskinesia at the administration of hydroxyzine due to hypersensitivity caused by prolonged treatment,[30] and therefore some contraindication is given for short-term administration of hydroxyzine to those with previous phenothiazine use.[30]

Side effects edit

Several reactions have been noted in manufacturer guidelines—deep sleep, incoordination, sedation, calmness, and dizziness have been reported in children and adults, as well as others such as hypotension, tinnitus, and headaches.[31] Gastrointestinal effects have also been observed, as well as less serious effects such as dryness of the mouth and constipation caused by the mild antimuscarinic properties of hydroxyzine.[31]

Central nervous system effects such as hallucinations or confusion have been observed in rare cases, attributed mostly to overdosage.[32][31] Such properties have been attributed to hydroxyzine in several cases, particularly in patients treated for neuropsychological disorders, as well as in cases where overdoses have been observed. While there are reports of the "hallucinogenic" or "hypnotic" properties of hydroxyzine, several clinical data trials have not reported such side effects from the sole consumption of hydroxyzine, but rather, have described its overall calming effect described through the stimulation of areas within the reticular formation. The hallucinogenic or hypnotic properties have been described as being an additional effect from overall central nervous system suppression by other CNS agents, such as lithium or ethanol.[33]

Hydroxyzine exhibits anxiolytic and sedative properties in many psychiatric patients. One study showed that patients reported very high levels of subjective sedation when first taking the drug, but that levels of reported sedation decreased markedly over 5–7 days, likely due to CNS receptor desensitization. Other studies have suggested that hydroxyzine acts as an acute hypnotic, reducing sleep onset latency and increasing sleep duration — also showing that some drowsiness did occur. This was observed more in female patients, who also had greater hypnotic response.[34] The use of sedating drugs alongside hydroxyzine can cause oversedation and confusion if administered at high doses—any form of hydroxyzine treatment alongside sedatives should be done under supervision of a doctor.[35][32]

Because of the potential for more severe side effects, this drug is on the list to avoid in the elderly.[36]

Pharmacology edit

Pharmacodynamics edit

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT2A | 170 (IC50) | Rat | [38] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | ND | ND |

| α1 | 460 (IC50) | Rat | [38] |

| D1 | >10,000 | Mouse | [39] |

| D2 | 378 560 (IC50) |

Mouse Rat |

[39] [38] |

| H1 | 2.0–19 6.4 100 (IC50) |

Human Bovine Rat |

[40][41][42] [43] [38] |

| H2 | ND | ND | ND |

| H3 | ND | ND | ND |

| H4 | >10,000 | Human | [41] |

| mACh | 4,600 10,000 10,000 (IC50) 6,310 (pA2) 3,800 |

Human Mouse Rat Guinea pig Bovine |

[44] [39] [38] [45] [43] |

| VDCC | ≥3,400 (IC50) | Rat | [38] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Hydroxyzine's predominant mechanism of action is as a potent and selective histamine H1 receptor inverse agonist.[46][47] This action is responsible for its antihistamine and sedative effects.[46][47] Unlike many other first-generation antihistamines, hydroxyzine has a lower affinity for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, and in accordance, has a lower risk of anticholinergic side effects.[43][47][48][49] In addition to its antihistamine activity, hydroxyzine has also been shown to act more weakly as an antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, the dopamine D2 receptor, and the α1-adrenergic receptor.[38][46] Similarly to the atypical antipsychotics, the comparably weak antiserotonergic effects of hydroxyzine likely underlie its usefulness as an anxiolytic.[50] Other antihistamines without such properties have not been found to be effective in the treatment of anxiety.[51]

Hydroxyzine crosses the blood–brain barrier easily and exerts effects in the central nervous system.[46] A positron emission tomography (PET) study found that brain occupancy of the H1 receptor was 67.6% for a single 30 mg dose of hydroxyzine.[52] In addition, subjective sleepiness correlated well with the brain H1 receptor occupancy.[52] PET studies with antihistamines have found that brain H1 receptor occupancy of more than 50% is associated with a high prevalence of somnolence and cognitive decline, whereas brain H1 receptor occupancy of less than 20% is considered to be non-sedative.[53]

Hydroxyzine also acts as a functional inhibitor of Acid sphingomyelinase.[54]

Pharmacokinetics edit

Hydroxyzine can be administered orally or via intramuscular injection. When given orally, hydroxyzine is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Hydroxyzine is rapidly absorbed and distributed with oral and intramuscular administration, and is metabolized in the liver; the main metabolite (45%), cetirizine, is formed through oxidation of the alcohol moiety to a carboxylic acid by alcohol dehydrogenase, and overall effects are observed within one hour of administration. Higher concentrations are found in the skin than in the plasma. Cetirizine, although less sedating, is non-dialyzable and possesses similar antihistamine properties. The other metabolites identified include a N-dealkylated metabolite, and an O-dealkylated 1/16 metabolite with a plasma half-life of 59 hours. These pathways are mediated principally by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5.[55][56] The N-dealykylated metabolite, norchlorcyclizine, bears some structural similarities to trazodone, but it has not been established whether it is pharmacologically active.[57][58] In animals, hydroxyzine and its metabolites are excreted in feces primarily through biliary elimination.[59][60] In rats, less than 2% of the drug is excreted unchanged.[60]

The time to reach maximum concentration (Tmax) of hydroxyzine is about 2.0 hours in both adults and children and its elimination half-life is around 20.0 hours in adults (mean age 29.3 years) and 7.1 hours in children.[5][6] Its elimination half-life is shorter in children compared to adults.[5] In another study, the elimination half-life of hydroxyzine in elderly adults was 29.3 hours.[7] One study found that the elimination half-life of hydroxyzine in adults was as short as 3 hours, but this may have just been due to methodological limitations.[61] Although hydroxyzine has a long elimination half-life and acts, in-vivo, as an antihistamine for as long as 24 hours, the predominant CNS effects of hydroxyzine and other antihistamines with long half-lives seem to diminish after 8 hours.[62]

Administration in geriatrics differs from the administration of hydroxyzine in younger patients; according to the FDA, there have not been significant studies made (2004), which include population groups over 65, which provide a distinction between elderly aged patients and other younger groups. Hydroxyzine should be administered carefully in the elderly with consideration given to possible reduced elimination.[32][better source needed]

Chemistry edit

Hydroxyzine is a member of the diphenylmethylpiperazine class of antihistamines.[medical citation needed]

Hydroxyzine is supplied mainly as a dihydrochloride salt (hydroxyzine hydrochloride) but also to a lesser extent as an embonate salt (hydroxyzine pamoate).[63][64][65] The molecular weights of hydroxyzine, hydroxyzine dihydrochloride, and hydroxyzine pamoate are 374.9 g/mol, 447.8 g/mol, and 763.3 g/mol, respectively.[4] Due to their differences in molecular weight, 1 mg hydroxyzine dihydrochloride is equivalent to about 1.7 mg hydroxyzine pamoate.[66]

Analogues edit

Analogues of hydroxyzine include buclizine, cetirizine, cinnarizine, cyclizine, etodroxizine, meclizine, and pipoxizine among others.

Society and culture edit

Brand names edit

Hydroxyzine preparations require a doctor's prescription. The drug is available in two formulations, the pamoate and the dihydrochloride or hydrochloride salts. Vistaril, Equipose, Masmoran, and Paxistil are preparations of the pamoate salt, while Atarax, Alamon, Aterax, Durrax, Tran-Q, Orgatrax, Quiess, and Tranquizine are of the hydrochloride salt.

References edit

- ^ "Atarax: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Vistaril: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Hubbard JR, Martin PR (2001). Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780824744977.

- ^ a b c "Hydroxyzine". United States National Library of Medicine (NLM). Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Paton DM, Webster DR (1985). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of H1-receptor antagonists (the antihistamines)". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 10 (6): 477–497. doi:10.2165/00003088-198510060-00002. PMID 2866055. S2CID 33541001.

- ^ a b Simons FE, Simons KJ, Frith EM (January 1984). "The pharmacokinetics and antihistaminic of the H1 receptor antagonist hydroxyzine". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 73 (1 Pt 1): 69–75. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(84)90486-x. PMID 6141198.

- ^ a b Simons KJ, Watson WT, Chen XY, Simons FE (January 1989). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies of the H1-receptor antagonist hydroxyzine in the elderly". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 45 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1038/clpt.1989.2. PMID 2562944. S2CID 24571876.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Hydroxyzine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ a b c British national formulary : BNF 74 (74 ed.). British Medical Association. 2017. p. X. ISBN 978-0857112989.

- ^ Shorter E (2009). Before Prozac: the troubled history of mood disorders in psychiatry. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195368741.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Hydroxyzine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Guaiana G, Barbui C, Cipriani A (December 2010). "Hydroxyzine for generalised anxiety disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006815. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006815.pub2. PMID 21154375.

- ^ a b United States Food & Drug Administration, (2004), p1

- ^ Smith E, Narang P, Enja M, Lippmann S (2016). "Pharmacotherapy for Insomnia in Primary Care". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 18 (2). doi:10.4088/PCC.16br01930. PMC 4956432. PMID 27486547.

- ^ Matheson E, Hainer BL (July 2017). "Insomnia: Pharmacologic Therapy". American Family Physician. 96 (1): 29–35. PMID 28671376.

- ^ Lippmann S, Yusufzie K, Nawbary MW, Voronovitch L, Matsenko O (2003). "Problems with sleep: what should the doctor do?". Comprehensive Therapy. 29 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1007/s12019-003-0003-x. PMID 12701339. S2CID 1508856.

- ^ Levander S, Ståhle-Bäckdahl M, Hägermark O (1 September 1991). "Peripheral antihistamine and central sedative effects of single and continuous oral doses of cetirizine and hydroxyzine". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 41 (5): 435–439. doi:10.1007/BF00626365. PMID 1684750. S2CID 25249362.

- ^ De Crescenzo F, D'Alò GL, Ostinelli EG, Ciabattini M, Di Franco V, Watanabe N, et al. (July 2022). "Comparative effects of pharmacological interventions for the acute and long-term management of insomnia disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 400 (10347): 170–184. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00878-9. hdl:11380/1288245. PMID 35843245. S2CID 250536370.

- ^ Burgazli CR, Rana KB, Brown JN, Tillman F (March 2023). "Efficacy and safety of hydroxyzine for sleep in adults: Systematic review". Human Psychopharmacology. 38 (2): e2864. doi:10.1002/hup.2864. PMID 36843057.

- ^ "Prescription For Addiction". 60 Minutes. CBS News. 9 December 2007. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ "Prometa Founder's Spotty Background Explored". Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. 3 November 2006. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ "UNITED STATES V. TERREN S. PEIZER". www.justice.gov. 1 March 2023.

- ^ Pelley S (7 December 2007). "Prescription For Addiction". 60 Minutes.

- ^ "Prometa under fire in Washington drug court program". Alcoholism & Drug Abuse Weekly. 20 (3). 21 January 2008. doi:10.1002/adaw.20121.

- ^ Ling W, Shoptaw S, Hillhouse M, Bholat MA, Charuvastra C, Heinzerling K, et al. (February 2012). "Double-blind placebo-controlled evaluation of the PROMETA™ protocol for methamphetamine dependence". Addiction. 107 (2): 361–369. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03619.x. PMC 4122522. PMID 22082089.

- ^ "Hydroxyzine - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com.

- ^ "Hydroxyzine".

- ^ a b c d e f United States Food & Drug Administration, (2004), p2

- ^ a b c Clark BG, Araki M, Brown HW (April 1982). "Hydroxyzine-associated tardive dyskinesia". Annals of Neurology. 11 (4): 435. doi:10.1002/ana.410110423. PMID 7103423. S2CID 41117995.

- ^ a b c UCB South-Africa, et al., (2004)

- ^ a b c United States Food & Drug Administration, (2004), p3

- ^ Marshik PL (2002). "Antihistamines". In Anderson PO, Knoben JE, Troutman WG (eds.). Handbook of Clinical Drug Data (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 794–796]. ISBN 978-0-07-136362-4.

- ^ Alford C, Rombaut N, Jones J, Foley S, Idzikowski C, Hindmarch I (1992). "Acute effects of hydroxyzine on nocturnal sleep and sleep tendency the following day: A C-EEG study". Human Psychopharmacology. 7 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1002/hup.470070104. S2CID 143580519.

- ^ Dolan CM (June 1958). "Management of emotional disturbances; use of hydroxyzine (atarax) in general practice". California Medicine. 88 (6): 443–444. PMC 1512309. PMID 13536863.

- ^ "NCQA's HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly" (PDF). NCQA.org. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Snowman AM, Snyder SH (December 1990). "Cetirizine: actions on neurotransmitter receptors". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 86 (6 Pt 2): 1025–1028. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(05)80248-9. PMID 1979798.

- ^ a b c Haraguchi K, Ito K, Kotaki H, Sawada Y, Iga T (June 1997). "Prediction of drug-induced catalepsy based on dopamine D1, D2, and muscarinic acetylcholine receptor occupancies". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 25 (6): 675–684. PMID 9193868.

- ^ Gillard M, Van Der Perren C, Moguilevsky N, Massingham R, Chatelain P (February 2002). "Binding characteristics of cetirizine and levocetirizine to human H(1) histamine receptors: contribution of Lys(191) and Thr(194)" (PDF). Molecular Pharmacology. 61 (2): 391–399. doi:10.1124/mol.61.2.391. PMID 11809864. S2CID 13075815. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- ^ a b Lim HD, van Rijn RM, Ling P, Bakker RA, Thurmond RL, Leurs R (September 2005). "Evaluation of histamine H1-, H2-, and H3-receptor ligands at the human histamine H4 receptor: identification of 4-methylhistamine as the first potent and selective H4 receptor agonist". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 314 (3): 1310–1321. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.087965. PMID 15947036. S2CID 24248896.

- ^ Anthes JC, Gilchrest H, Richard C, Eckel S, Hesk D, West RE, et al. (August 2002). "Biochemical characterization of desloratadine, a potent antagonist of the human histamine H(1) receptor". European Journal of Pharmacology. 449 (3): 229–237. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02049-6. PMID 12167464.

- ^ a b c Kubo N, Shirakawa O, Kuno T, Tanaka C (March 1987). "Antimuscarinic effects of antihistamines: quantitative evaluation by receptor-binding assay". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 43 (3): 277–282. doi:10.1254/jjp.43.277. PMID 2884340.

- ^ Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (May 1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–565. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217. S2CID 21236268.

- ^ Orzechowski RF, Currie DS, Valancius CA (January 2005). "Comparative anticholinergic activities of 10 histamine H1 receptor antagonists in two functional models". European Journal of Pharmacology. 506 (3): 257–264. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.11.006. PMID 15627436.

- ^ a b c d Szepietowski J, Weisshaar E (2016). Itin P, Jemec GB (eds.). Itch - Management in Clinical Practice. Current Problems in Dermatology. Vol. 50. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. pp. 1–80. ISBN 9783318058895.

- ^ a b c Hosák L, Hrdlička M (2017). Psychiatry and Pedopsychiatry. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. p. 364. ISBN 9788024633787.

- ^ Berger FM (May 1957). "The chemistry and mode of action of tranquilizing drugs". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 67 (10): 685–700. Bibcode:1957NYASA..67..685B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb46006.x. PMID 13459139. S2CID 12702714.

- ^ Tripathi KD (2013). Essentials of Medical Pharmacology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 165. ISBN 9789350259375.

- ^ Stein DJ, Hollander E, Rothbaum BO, eds. (2009). Textbook of Anxiety Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. p. 196. ISBN 9781585622542.

- ^ Lamberty Y, Gower AJ (September 2004). "Hydroxyzine prevents isolation-induced vocalization in guinea pig pups: comparison with chlorpheniramine and immepip". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 79 (1): 119–124. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.015. PMID 15388291. S2CID 23593514.

- ^ a b Tashiro M, Kato M, Miyake M, Watanuki S, Funaki Y, Ishikawa Y, et al. (October 2009). "Dose dependency of brain histamine H(1) receptor occupancy following oral administration of cetirizine hydrochloride measured using PET with [11C]doxepin". Human Psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 540–548. doi:10.1002/hup.1051. PMID 19697300. S2CID 5596000.

- ^ Yanai K, Tashiro M (January 2007). "The physiological and pathophysiological roles of neuronal histamine: an insight from human positron emission tomography studies". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 113 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.06.008. PMID 16890992.

- ^ Sánchez-Rico M, Limosin F, Vernet R, Beeker N, Neuraz A, Blanco C, et al. (December 2021). "Hydroxyzine Use and Mortality in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: A Multicenter Observational Study". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (24): 5891. doi:10.3390/jcm10245891. PMC 8707307. PMID 34945186.

- ^ "Ucerax (hydroxyzine hydrochloride) 25 mg film-coated tablets. Summary of product characteristics" (PDF). Irish Medicines Board. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Foye WO, Lemke TL, Williams DA (2013). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. OCLC 748675182.

- ^ Thavundayil JX, Hambalek R, Kin NM, Krishnan B, Lal S (1994). "Prolonged penile erections induced by hydroxyzine: possible mechanism of action". Neuropsychobiology. 30 (1): 4–6. doi:10.1159/000119126. PMID 7969858.

- ^ Malcolm MJ, Cody TE (January 1994). "Hydroxyzine and Possible Metabolites". Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal. 27 (2): 87–92. doi:10.1080/00085030.1994.10757029.

- ^ "Vistaril (hydroxyzine pamoate) Capsules and Oral Suspension" (PDF). pfizer.com. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

This paper says "The extent of renal excretion of Vistaril has not been determined"

- ^ a b Pong SF, Huang CL (October 1974). "Comparative studies on distribution, excretion, and metabolism of hydroxyzine-3H and its methiodide-14C in rats". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 63 (10): 1527–1532. doi:10.1002/jps.2600631008. PMID 4436782.

- ^ Kacew S (1989). Drug Toxicity & Metabolism In Pediatrics. CRC Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780849345647.

- ^ Simons FE (May 1994). "H1-receptor antagonists. Comparative tolerability and safety". Drug Safety. 10 (5): 350–380. doi:10.2165/00002018-199410050-00002. PMID 7913608. S2CID 12749971.

- ^ Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 671–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- ^ "Hydroxyzine Pamoate 5 mg/ML Oral Suspension". Archived from the original on 17 October 2020.