Summary

Irataba (Mohave: eecheeyara tav [eːt͡ʃeːjara tav], also known as Yara tav, Yarate:va, Arateve; c. 1814 – 1874) was a leader of the Mohave Nation, known as a mediator between the Mohave and the United States. He was born near the Colorado River in present-day Arizona. Irataba was a renowned orator and one of the first Mohave to speak English, a skill he used to develop relations with the United States.

Irataba | |

|---|---|

Yara tav | |

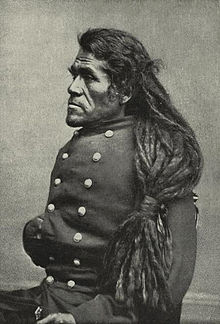

Irataba, c. 1864 | |

| Mohave leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1814 Arizona |

| Died | May 3 or 4, 1874 (aged 59–60) Colorado River Indian Reservation, Arizona Territory, United States |

| Mother tongue | Mohave |

Irataba first encountered European Americans in 1851, when he assisted the Sitgreaves Expedition. In 1854, he met Amiel Whipple, then leading an expedition crossing the Colorado. Several Mohave aided the group, and Irataba agreed to escort them through the territory of the Paiute to the Old Spanish Trail, which would take them to southern California. Noted for his large physical size and gentle demeanor, he later helped and protected other expeditions, earning him a reputation among whites as the most important native leader in the region.

Against Irataba's advice, in 1858 Mohave warriors attacked the first emigrant wagon train to use Beale's Wagon Road through Mohave country. As a result, the U.S. War Department sent a detachment under Colonel William Hoffman to pacify the tribe. Following a series of confrontations known as the Mohave War, Hoffman succeeded in dominating the natives, and demanded that they allow the passage of settlers through their territory. To ensure compliance, Fort Mohave was constructed near the site of the battle in April 1859. Hoffman also imprisoned several Mohave leaders. Having been an advocate for friendly relations with the whites, Irataba became the nation's Aha macave yaltanack, an elected, as opposed to hereditary, leader.

As a result of his many interactions with U.S. officials and settlers, Irataba was invited to Washington, D.C., in 1864, for an official meeting with members of the U.S. military and its government, including President Abraham Lincoln. In doing so, he became the first Native American from the Southwest to meet an American president. He received considerable attention during his tours of the U.S. capital, and of New York City and Philadelphia, where he was given gifts, including a silver-headed cane from Lincoln. Upon his return he negotiated the creation of the Colorado River Indian Reservation, which caused a split in the Mohave Nation when he led several hundred of his supporters to the Colorado River valley. The majority of the Mohave preferred to remain in their ancestral homelands near Fort Mohave and under the leadership of their hereditary leader, Homoseh quahote, who was less enthusiastic about direct collaboration with whites. As leader of the Colorado River band of Mohave, Irataba encouraged peaceful relations with whites, served as a mediator between the warring tribes in the area, and during his later years continued to lead the Mohave in their ongoing conflicts with the Paiute and Chemehuevi.

As noted by ethnographer Lorraine Sherer, "to some he is an heroic figure, to others he was a white collaborator who did not stand up for Mojave rights."[1] The Irataba Society, a non-profit charity run by the Colorado River Indian Tribes, was established in 1970 in Parker, Arizona, where a sports venue, Irataba Hall, is also named after him. In 2002, the US Bureau of Land Management designated 32,745 acres (132.51 km2) in the Eldorado Mountains as Ireteba Peaks Wilderness. In March 2015, Mohave Tribal chairman Dennis Patch credited Irataba with ensuring that "the Mohaves stayed on land they had lived on since time immemorial."[2]

Background edit

Irataba's name, also rendered as Ireteba, Yara tav, Arateve, Yarate:va, and Yiratewa, derives from the Mohave language phrase eecheeyara tav, which means "beautiful bird".[4] He was born into the Neolge, or Sun Fire clan of the Mohave Nation c. 1814.[5][a] He lived near a rock formation that gave its name to Needles, south of where the Grand Canyon empties into the Mohave Canyon in present-day Arizona, near the Nevada and California border.[6] The Mohave lived in houses along the riverbank in the Mohave Valley, during winter in half-buried dwellings built with cottonwood logs and arrowweed covered in earth, and in the summer in open-air flat-roofed houses called ramadas.[7]

In the mid-19th century, the Mohave were composed of three geographical groups; Irataba was the hereditary leader of the Huttoh Pah group, who lived near the east bank of the Colorado River and occupied the central portion of the Mohave Valley.[8] Mohave government consisted of a loose system of hereditary clan leaders with a head of the entire nation.[9] They were often involved in conflicts with the Chemehuevi, Paiute, and Maricopa peoples.[10] Irataba was a member of the Mohave warrior society called kwanami, who led groups of warriors in battle and were dedicated to defending their lands and people.[11][12]

Little is known of Irataba's family relations, except for the name of his son Tekse thume, and his nephews Qolho qorau (Irataba's sister's son who succeeded him as leader) and Aspamekelyeho.[13] Olive Oatman, who lived with the Mohave for five years, later stated that Irataba was the brother of the former chief, presumably Cairook, with whom Irataba clearly had a close relation.[14] One anecdotal description states that Irataba had several wives, among them a Hualapai woman who had been taken as a captive and who is also described as having a young son.[15] He also had at least one daughter, the mother of his granddaughter Tcatc who was interviewed in the 1950s. She stated that Irataba had wanted to leave his land deeds and medals to his brother's sons, but that they were eventually lost.[16]

In contemporary accounts Irataba was described as an eloquent speaker, and linguist Leanne Hinton suggests that he was among the first Mohave people to become fluent in English, which he learned through his many interactions with Anglo-Americans.[17] Like many Mohave men, Irataba was very tall, particularly by 19th-century standards; the United States Army estimated his height at 6 feet 4 inches (193 cm) in 1861.[18] American author Albert S. Evans, writing in The Overland Monthly, referred to him as "the old desert giant".[19] Edward Carlson, a soldier based at Fort Mohave who knew Irataba well in the 1860s, described him as having a powerful frame, but also a "very gentle" and "kind ... demeanor".[20]

Irataba lived through a tumultuous period of Mohave history where the people went from being a politically independent nation to coming under the political control of the United States, and the events surrounding his role in these encounters are well documented. Most historical sources for the life of Irataba come from descriptions by white explorers or government agents with whom he interacted, or from contemporary newspapers that reported on his visits to the East Coast and California, and on the conflicts in Arizona territory. Some Mohave versions of the events also exist: in the early 20th century anthropologist A. L. Kroeber interviewed Jo Nelson (Mohave: Chooksa homar), a Mohave man who participated in many of the events and knew Irataba personally;[21] another version was told to ethnographer George Devereux by Irataba's granddaughter Tcatc,[16] and versions recounted by members of the Fort Mohave band of Mohave, the descendants of Homoseh quahote, were recorded by ethnographer Lorraine Sherer during the 1950s and 1960s.[22]

Contact with emigrants and explorers edit

Irataba assisted Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves during his 1851 exploration of the Colorado.[5] On March 19, 1851, a family of Brewsterite settlers, the Oatmans, who were traveling by wagon train in what is now Arizona, were attacked by a band of Western Yavapai, probably the Tolkepaya.[23] They captured two survivors of the attack: the 14-year-old Olive Oatman and her 7-year-old sister, Mary Ann. After a year with the Yavapai, the girls were sold to the Mohave, and adopted into the Oach clan where they lived with the family of a Mohave man called Tokwatha (Musk Melon) a friend of Irataba. Olive remained with the Mohave until February 22, 1856, when Tokwatha, having been warned that having a white girl among them might be seen as an offense by whites, brought her to Fort Yuma carpenter Henry Grinnell, releasing her in return for two horses and some blankets and beads.[24] Irataba may have learned about Anglo-Americans and their society from Oatman, and knowing her may have contributed to his generally favourable disposition towards Whites.

Whipple Expedition edit

On February 23, 1854, Irataba, Cairook, and other Mohave people encountered an expedition led by military officers Amiel Whipple and J.C. Ives, as the group approached the Colorado en route to California.[25][b] Whipple and his men counted six hundred Mohave gathered near their camp, trading corn, beans, squash (plant), and wheat for beads and calico.[29] By the end of their commerce, the party had purchased six bushels of corn and two hundred pounds of flour.[30] The Mohave played a traditional game played with a hoop and pole, and the two groups entertained themselves with target practice, the Mohave using bows and arrows and the whites firing pistols and rifles.[30] When the expedition had difficulty crossing the Colorado on February 27, several Mohave jumped into the water and helped salvage the supplies.[31]

Irataba and Cairook agreed to escort the group across the territory of the Paiute to the Old Spanish Trail that would take them to southern California.[32] German artist Balduin Möllhausen accompanied the Whipple expedition, and made drawings of several Mohave, including Irataba. Möllhausen's drawings were featured in Ives' 1861 congressional report, making Irataba "among the first named likenesses of California Indians ever published".[33]

Ives Expedition edit

In February 1858, Ives returned to the area in a paddle steamer named Explorer. He was leading an expedition up the Colorado from the south, and he wanted Irataba to guide them.[34] The Mohave gave permission to navigate the river, and Cairook, Irataba, and a 16-year-old Mohave boy named Nahvahroopa joined them.[35] Möllhausen again accompanied the expedition, and was impressed with the Mohave guides, later noting Irataba's enthusiastic handshake and lamenting that their only form of communication was sign language. He also noted that Irataba and the Mohave readily began wearing European clothes given to them by members of the expedition, and showed great interest in smoking tobacco.[36] Aside from the friendship shown to him by Irataba and Cairook, Ives noted that the Mohave appeared less friendly than on earlier occasions, a change that he attributed to their contact with Mormons, who were in conflict with the US and had succeeded in converting some Mohave.[37][38][c]

Irataba guided the party into the Mohave Canyon, indicating the location of rapids and advising the Explorer's pilot of convenient places to anchor while camping for the night.[40] When they reached the entrance to the Black Canyon of the Colorado, the ship crashed against a submerged rock, throwing several men overboard, dislodging the boiler, and damaging the wheelhouse. Using their skiff, the crew towed the Explorer to the shore, where they camped for three days while repairing the vessel.[41] The expedition had relied on beans and corn provided by the Mohave during the previous weeks; as their supplies dwindled they grew increasingly anxious about the arrival of a resupply pack train from Fort Yuma. Irataba volunteered to hike towards the Mohave Valley to try to locate the supplies that had been requested several days earlier. He also warned that the expedition was being watched by Paiutes.[42]

When Irataba returned he informed Ives that he would not venture any deeper into the territory of the Hualapais, but agreed to help them locate friendly guides in the region before parting company.[43] Irataba was reluctant to venture into the canyon because he feared the party would be ambushed by Paiutes aligned with Mormons.[44] After enlisting three Hualapai guides, Irataba prepared to take his leave from the expedition and return to the Mohave community.[45] On April 4, the Mohave received payment for their services; Möllhausen described the exchange: "Lieutenant Ives informed Irataba that he had been authorized by the 'Great Grandfather in Washington' to give him two mules ... for his loyalty and his trustworthiness so that he could take his possessions and those of his companions more conveniently to his home valley."[46] The next morning, as they were preparing to leave: "Irataba was visibly moved ... and in his sincere eyes expressed so much honesty and loyalty as can only be found in an unspoiled nature ... I maintain that there was not one in our expedition who did not feel a certain sadness to see this huge man with ... a harmless soul leave."[46]

Mohave War and aftermath edit

Following their experiences with the Sitgreaves and Whipple expeditions, and encounters with Mormons and the soldiers at Fort Yuma, the Mohave were aware that whites were immigrating to the region in increasing numbers. It was difficult for the Mohave to predict the behavior of the arriving whites, some of whom, like Whipple, were amiably disposed towards them, whereas others such as the Mormons were hostile. The kwanami were divided on how the situation should be approached; some advocated an aggressive posture, denying whites all passage through their territory, but others, including Irataba, preferred a peaceful approach, or even an alliance with them that could put the Mohave in a stronger position relative to their traditional enemies the Paiute, Chemehuevi, and Walapai.[11]

On September 1, 1857, a joint force of Mohave and Quechan warriors launched a major attack with hundreds of warriors on a Maricopa village close to Maricopa Wells, Arizona, on the Gila river. The Battle of Pima Butte was described by a group of white mail carriers who witnessed it. They stated that the battle was fought mostly with clubs, as well as bows and arrows, and that probably more than 100 warriors died, most of them from the attacking party. It is unknown whether Irataba participated in the attack, but given his status as kwanami, it is likely that he did. The battle has been described as the last major battle involving only Native American nations.[47] This defeat put the Mohave on the defensive, wary of the possibility that whites would take this moment of weakness as an opportunity to begin settling on tribal lands.[48][38]

Rose–Baley Party attack edit

In October 1857, an expedition led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale was tasked with establishing a trade route along the 35th parallel from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Los Angeles, California.[49][50] From Fort Smith, his journey continued through Fort Defiance, Arizona, before crossing the Colorado near Needles, California.[5] This route became known as Beale's Wagon Road, and the location where Beale crossed the river as Beale's Crossing.[51] Beale's journal and subsequent report to the United States Secretary of War did not mention any problems with Irataba and the Mohave, but an assistant named Humphrey Stacy recorded that the Mohave had prevented Beale from traveling downriver.[52]

In 1858, the Rose–Baley Party comprising at least a hundred settlers with wagons and a large herd of cattle, was the first emigrant train to venture onto Beale's Wagon Road.[53][d] Upon entering Mohave territory the settlers started cutting down cottonwood trees, which were an important resource for the Mohave. The most warlike of the kwanamis organized an attack on the party, and drove away and slaughtered many of the party's cattle.[55] On August 30, three hundred Mohave warriors attacked the emigrants but were repelled, with one member of the party killed in battle and eleven wounded. Another family who were not with the main party during the attack were killed in an event that has often been blamed on the Mohave, but which in Colonel William Hoffman's opinion was more likely carried out by a band of Walapai, along with seven renegade Mohave.[56] The emigrants killed seventeen Mohave warriors.[50][57] The incident was widely publicized in the media and labeled "a massacre",[58] scaring many white Californians who feared being cut off from the eastern US by hostile natives, and it motivated the War Department to quickly subjugate the tribe.[59][48]

Irataba was away at Fort Yuma during the attack on the settlers, and upon hearing of it he scolded the Mohave. Chooksa homar participated in the events and reported that Irataba told the warriors, "I hear you fought, though I told you not to. And you will have war again: I know it. You used to fight the Maricopa. I want to go [to Phoenix] to see the Maricopa and tell them: 'The Mohave will not come any more to attack you'."[60] Irataba, weary of the constant fighting and worried that further conflicts with neighboring tribes would draw more attention from the US soldiers, organized a peace expedition to the Maricopa, settling the ancient disputes between the two peoples.[61]

Conflict with the US army edit

When news of the attack reached California, the US War Department decided to establish a military fort at Beale's Crossing to keep the Mohave under control and secure white travelers safe passage through Mohave lands. On December 26, 1858, Hoffman and fifty dragoons from Fort Tejon were dispatched to cross the desert and confront the Mohave.[62] Irataba attempted to arrange a peaceful meeting, but Hoffman ordered his troops to fire on the warriors, who counterattacked and repelled the force.[63] He returned in April 1859, by way of Fort Yuma, with four companies of the 6th Infantry Regiment.[62] When they arrived at Beale's Crossing, the Mohave decided against attacking the army of five hundred soldiers.[62] On April 23, at Hoffman's request, he and his officers met with several hundred Mohave warriors and their leaders. The indigenous leaders included Cairook, Irataba, Homoseh quahote (also called Seck-a-hoot and Asika hota), and Pascual, leader of the Quechan.[64] During the meeting the Mohave were surrounded by armed soldiers who prevented them from leaving.[65]

Hoffman gave the Mohave a choice between war and peace, and he demanded that they agree to never again harm white settlers along the wagon trail. He also declared that, as punishment, the Mohave were required to surrender as hostages a member of each clan and three warriors who had taken part in the attack.[65] Hoffman demanded that the chief who had ordered the attack on the settlers offer himself up as a hostage. According to Chooksa homar, the chief who had ordered the attack was Homoseh quahote, who was reluctant to give himself up. Cairook offered himself in his place, along with eight others, including Tokwatha, Irataba's son Tekse thume, and Irataba's nephews Qolho qorau, and Aspamekelyeho. Other hostages were named Itsere-'itse, Ilyhanapau, and Tinyam-isalye.[66] They were transported in the river steamer General Jessup to Fort Yuma.[67] Many soldiers remained to begin construction on the Beale's Crossing fort, which was named Fort Mohave.[68] Although Irataba visited the garrison several times and argued for their release, the hostages were held for more than a year.[69] On June 21, 1859, Cairook and one other captive were killed by soldiers while attempting to escape their incarceration.[70] Most of the other Mohave captives escaped.[70][71]

In July 1861, the commander of Fort Mohave, Major Lewis Armistead, ordered soldiers to fire into a group of Mohave who he suspected of having attacked a mail carrier and slaughtered his mule. The Mohave did not respond violently to the attack, but Armistead decided to punish them for harassing the mail party. He arrived at Irataba's ranch where a group of Mohave boys were planting beans, and from a hidden position he shot one of the planters, killing him. This attack prompted an assault on Armistead's detachment, who from an advantageous position on the high ground were able to repel the Mohave, killing many of them in a battle that lasted most of the day. Armistead's report of the assault of Irataba's ranch reported 23 dead Mohave warriors, but the Mohave remember a much higher number of casualties, including women and children killed by the soldiers. Sherer speculated that, given that 50 soldiers fired around 10 shots each, the casualty count could have been much higher than reported. The attack on Irataba's ranch is remembered by the Mohave as "the first and last battle with the Federal Troops."[72]

As Aha macave yaltanack edit

After Cairook's death, whites living near the Colorado River began to view Irataba as the main leader of the Mohave.[73] He had become Aha macave yaltanack (leader of the Mohave Nation) or hochoch (leader elected by the people); "yaltanack" is Mohave for "leader", and "hochach" means "head of a group".[74] Homoseh quahote was a hereditary leader of the Malika clan ("the understanding people"), and the position of head of the Mohave was traditionally inherited only by someone from that clan. Because Irataba was of the Huttoh pah, in order for him to become the leader of the Mohave Nation, Homoseh quahote had to step down so Irataba, as an elected leader, could take his place.[75]

Despite the accepted English translations, the words yaltanack and huchach do not mean a "ruler" or "boss".[76] Devereux describes Mohave government as "one of the least understood segments of Mohave culture", and notes that while white officials "tended to act on the assumption that Indian chiefs exercised absolute authority", as an elected leader Irataba was "primarily a servant of the tribe".[77]

By the mid-1860s a deep rift had developed between Irataba, who was proactive in cooperating with white settlers, and Homoseh quahote, who passively tolerated but did not approve of white encroachment on Mohave lands.[78] Irataba was Aha macave yaltanack of the Mohave from 1861 to 1866, but from 1867 to 1869 opinions differ, and by 1870 US government correspondence suggests that Homoseh quahote had succeeded him as leader of the Fort Mohave group.[79]

Mining ventures edit

Probably first to bring national attention to the potential gold in the region was F. X. Aubry, who in 1853 reported finding gold at a crossing of the Colorado and that he traded for legendary gold bullets further east with Tonto Apache. Newspapers across the country copied the gold strike story.[80] Over the next decade mining discoveries up and down the lower Colorado River valley brought miners into newly formed mining districts.[81] In the spring of 1861, Mohave, possibly including Irataba, aided a group of prospectors discover gold in Eldorado Canyon north east of Ft. Mohave, site of first mining rush to the immediate area.[82] This was followed by the discovery of the San Francisco district (now Oatman district), where Irataba led John Moss to the rich Moss lode.[83] Earlier, concern for protecting incoming miners brought together tribal leaders to Ft. Yuma in April 1863, including Irataba, where they pledged to allow prospectors into their country. On his return home, the Mohave joined a prospecting party led by mountain man Joseph R. Walker who had prospected among them on the river in 1860.[84] In 1863, Irataba acted as a guide for the Walker Party, gold prospectors led by Walker and including Jack Swilling, who later founded Phoenix, Arizona. Irataba brought them to a river that he called Hasyamp, later named the Hassayampa River, where they found plentiful gold. Central Arizona's first mining district was established there the following year, which led to the founding of Prescott, Arizona soon afterward.[85] Relations between settlers and the Mohave were positive during this period, but as emigration increased, gold seekers founded towns, largest on the river being named La Paz, stirring fear among settlers of a native uprising against further encroachment on Mohave land.[86] The following year a group of soldiers from Fort Mohave discovered an area between Needles, Fort Mohave, and the Colorado River that was abundant in copper ore. The parcel was named Irataba Mining District, and within the year a mining company had been formed to work it. A small mining town named Irataba City was established on a bluff two miles below Fort Mohave.[87][88] High copper market prices during the Civil War brought into operation the Bill Williams Fork copper mines as well, which shipped copper ore from the new Colorado River landing of Aubry. Though there would be down turns, mining in the Mohave lands was now well established.

Travels edit

As related above, during the early 1860s, Irataba befriended prospectors as a guide. One of them was John Moss, whom Irataba had shown the location of a gold mine in the Mojave desert, which Moss later sold.[89][15] Moss suggested Irataba be invited to Washington so that he could see firsthand the United States' military might.[90][e] In November 1863, Irataba traveled with Moss to San Pedro, Los Angeles, where they boarded the steamship Senator, bound for San Francisco. In San Francisco, he stayed at the Occidental Hotel and created a storm as he walked down Jackson Street, dressed in clothing typical of European Americans, which Irataba soon preferred to traditional Mohave clothing.[92] The press documented his every movement and wrote extensively about his physical size and strong features.[20] On December 2, 1863, the Daily Evening Bulletin described Irataba as a large man, "granitic in appearance as one of the Lower Coast mountains, with ... a lower jaw massive enough to crush nuts or crush quartz."[92]

In January 1864 they sailed for the Isthmus of Panama on board the Orizaba, then traveled onwards to New York City.[93] Upon Irataba's arrival in New York, Harper's Weekly described him as "the finest specimen of unadulterated aboriginal on this continent".[94] Here Irataba exchanged his suit and sombrero for the uniform and regalia of a major general, including a bright yellow sash, a gold badge encrusted with precious stones, and a medal with the inscription, "Irataba, Chief of the Mohaves, Arizona Territory".[95] In February, when The New York Times asked him to explain the nature of his visit, he replied: "to see where so many pale faces come from".[96] In New York he met with the former Mohave resident Olive Oatman, and the two conversed in Mohave. Irataba told Oatman that her Mohave adoptive sister Topeka, to whom she had grown very close, still missed her and hoped she would return.[97] Oatman described the encounter as a meeting between friends.[97]

Irataba moved on to Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., where he earned great acclaim; government officials and military officers lavished him with gifts of medals, swords, and photographs.[98] In Washington he met with President Abraham Lincoln, who gave him a silver-headed cane.[99] He was the first Native American from the Southwest to meet an American president.[100] The tour ended in April, when he and Moss sailed to California, again by way of Panama, and made their way back to Beale's Crossing from Los Angeles by wagon.[95]

Upon Irataba's return from Washington D.C., he met with the Mohave while dressed in his major general's uniform, with medals. He wore a European-style hat and carried a long Japanese sword, and he told the Mohave about all the things he had seen.[101] He tried to convince them that peace with the United States was in their best interests, and that war against them was futile, stressing their dominant military capabilities.[102] Many Mohave were skeptical of his reports, and reacted with disbelief.[103]

Colorado River Indian Reservation edit

The completion of Fort Mohave began the process of military subjugation of the Mohave, and the next step was the establishment of reservations. In 1863, Charles Debrille Poston, the first Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Arizona Territory, called a conference between the Chemehuevi and Irataba's faction of the Mohave, in which he convinced them to form an alliance with the US against the Apache. The treaty was never ratified by the US Congress but formed an important step in establishing friendly relations between the Mohave and the US government following the military campaigns and the establishment of Fort Mohave.[104]

Poston promoted the idea of establishing a reservation in the southern portion of Mohave country. Many Mohave opposed the proposed location and instead argued for a smaller parcel further north in the Mohave Valley, which had more fertile land.[105] With Irataba and an engineer, Poston traveled down the Colorado River to survey a location.[106] In August 1864 the post commander at Fort Mohave, Captain Charles Atchisson, stated that Irataba was against the proposed location. In September 1864, Poston gave the impression that Irataba was in favor of it.[107] In a letter to General Richard C. Drum, Atchisson reported that Irataba and four Mohave leaders were unhappy with how Poston was handling the situation:

Mr. Poston had marked out a reservation for the Mojave Indians in the upper part of the La Paz valley on the East side of the Colorado River ... Iratabu says this reservation is covered with sand and unfit for cultivation and the Indians are opposed to giving up their good lands in the Mojave Valley and moving to it ... Iratabu says if he can have the valley below the Fort Mojave reserved for the home of the Indians, he is willing to give up all claims to lands on other parts of the river, and bring his Indians from La Paz and other points to this valley ... I have full confidence in the friendship of Iratabu towards white men, but not in his tribe, if troubles with any other Indians should occur, while he has more influence over them than any other chief, his control over them is not complete, and they are as likely to lead him (as he is them).[107]

Faced with Irataba's disagreement, Poston promised that the US government would assist the Mohave with installing an irrigation system at the Colorado that would make most of the reservation arable.[108] This apparently convinced Irataba, who traveled to the Colorado River Valley with about 800 people, almost a fifth of the entire Mohave Nation.[109] General James Henry Carleton thought a reservation was unnecessary, and engineer Herman Ehrenberg disagreed with Poston's proposed location on the basis that the soil was too alkaline for farming, the need for irrigation too great, and the task of raising the river too insurmountable. Nonetheless, on March 3, 1865,[110] Congress established the Colorado River Indian Reservation at Poston's proposed location.[111] Ehrenberg's concerns proved valid, and neither Poston nor any subsequent US authority was willing to dedicate the considerable resources required to make the location suitable for farming.[108] The reservation was established without a treaty having been established between the Mohave and the US government.[112] The boundaries were expanded and clarified by executive orders issued by President Grant in 1873, 1874 and 1867.[112][110]

Most of the Mohave refused to leave their ancestral homelands for the reservation, but Irataba's conviction that the reservation was their best option marked the beginning of a rift between his group and those who stayed behind to follow Homoseh quahote, the nation's hereditary leader.[113] According to an eyewitness account by Chooksa homar, Irataba explained his decision to move:

"You get angry sometimes; I know you are brave men and think you can beat anybody. You thought you could beat the whites: you said so. I told you you could not; the whites have beaten all tribes; all are friends to them now. You did not listen to what I said when I told you that. You did what you thought, and many have got killed. If the soldiers come, you cannot resist them. You did not know that, but now you know it. The country down river from here, which we took away from another tribe [the Halchidhoma], I will live there. Those of you who want to go on fighting can stay here. I do not want to and will leave you."[114]

As the promised irrigation assistance was not immediately forthcoming, the first year at the reservation brought a drought that made it necessary for the Mohave to request food assistance. In 1867, Irataba and the Mohave began to build an irrigation canal, digging by hand a ditch that ran for 9 miles (14 km).[108][f] A report by a US official visiting the reservation in 1870 recorded that attempts by the Mohave at agricultural cultivation on the site were restricted to an area of not more than 40 acres (16 ha).[115]

Later years edit

Irataba continued to lead the Colorado River band of Mohave during the 1860s. He pursued peaceful relations with the surrounding tribes and cooperated actively with US authorities. He also helped the Yavapai and Walapai in ongoing conflicts with Paiutes and Chemehuevi.[117]

In March 1865, Irataba and the Mohave defeated the Chemehuevi after their allies, the Paiutes, killed two Mohave women.[118] The Mohave pushed the Chemehuevi off their traditional territory and into the California desert, but they soon returned.[119] To avoid fighting a two-front war, Irataba attacked the Chemehuevi first, then turned his attention to the Paiutes, who were planning an attack on the Mohave farm and granary on the Colorado's Cottonwood Island.[120] During a subsequent battle with the Chemehuevi in October 1865, Irataba was taken prisoner while wearing his major general's uniform.[121] According to a contemporary news report based on second hand accounts from white travelers, the captors feared that killing him would invite repercussions from the soldiers stationed at Fort Mohave, so they instead stripped him naked and sent him home badly beaten.[120] In the Mohave account of the events as told by Chooksa homar, Irataba surrendered in an effort to make peace with the Chemehuevi, and offered his uniform to their chief as a gesture of peace.[122] In 1867, a treaty signed by Irataba and the Chemehuevi leader Pan Coyer restored peaceful relations between the two nations.[123]

The old man is here now with his tribe, but he looks feeble, wan, and grief stricken. Age has come to Irataba, but it has brought to him no bright and peaceful twilight. Dark and cheerless appear the skies of his declining years.[124][g]

—The Arizona Weekly Miner, February 5, 1870

Irataba also welcomed bands of Yavapai onto the reservation after they had been subject to massacres by US troops, or suffered starvation due to having been driven from their lands. The meager resources of the reservation proved unable to sustain the additional population and eventually the Yavapai had to leave. Irataba frequently served as a mediator between Yavapai and Walapai who had become embroiled in conflicts with the US army, and participated in peace parlays. In 1871–72, General George Crook came to the Mohave reservation looking for a group of Yavapai thought to be responsible for the Wickenburg Massacre, and Irataba had no choice but to turn the war party over to the army.[123] He traveled to the trial proceedings at Fort Date Creek, where he was instructed to hand tobacco to the Yavapai he believed to be responsible, as a way for him to testify against them without their realizing it. As soldiers attempted to arrest the men that Irataba identified, fighting broke out and one of the Yavapai leaders, Ohatchecama, and his brother were shot.[126] Despite having been shot twice and stabbed with a bayonet, Ohatchecama survived and escaped to organize the Tolkepaya Yavapai in resistance against the US army.[127] The Yavapai felt betrayed by Irataba, and plotted to kill him in revenge, but were eventually persuaded that he was not the one who had turned them over to Crook.[128][129]

The Colorado River band of Mohave never replaced Irataba; he was their leader when he died at their reservation on May 3 or 4, 1874.[124] His cause of death is unknown, but smallpox and natural causes are both cited.[102] The Mohave grieved deeply; Irataba's cremation and the rituals of mourning were reported in newspapers as far away as Omaha, Nebraska.[130][h] Irataba was succeeded as leader on the Colorado Reservation by his nephew, Qolho qorau of the Vemacka clan, who upheld his uncle's policies.[133]

Legacy and influence edit

In 1966, Sherer commented regarding Irataba's legacy amongst the Mohave: "Estimation of his position in Mojave history from the Mojave viewpoint differs. To some he is an heroic figure, to others he was a white collaborator who did not stand up for Mojave rights. From the standpoint of white men who were conquering a wilderness, he was indeed the Mojave who worked unswervingly for peace."[1]

Irataba's influence as a leader may even have left its mark on the Mohave language. A list of Mohave words that he dictated to an anthropologist during his visit in Washington shows that he was among the first Mohave speakers to shift the sounds [s] and [ʂ] (similar to sh as in "shack") to [θ] (th as in "thick") and [s], respectively. By the late 19th century all Mohave speakers had adopted this change. Linguist Leanne Hinton has suggested that this may be due in part to Irataba's influence, both because he was a prestigious leader whose ways of speaking may have been emulated by other Mohave, and also because when he led the Mohave onto the reservation the old distinctions between dialect groups were erased through dialect leveling, making new changes spread quickly through the community.[134]

The Irataba Society, a non-profit charity run by the Colorado River Indian Tribes, was established in Parker, Arizona, in 1970.[135] The charity holds an annual pow wow or National Indian Days celebration.[136] Irataba Hall, a sports venue in Parker, is also named after him.[137] In 2002, the US Bureau of Land Management designated 32,745 acres (13,251 ha) of the Eldorado Mountains, contained largely within the Lake Mead National Recreation Area, as Ireteba Peaks Wilderness.[138]

In March 2015, the Colorado River Indian Tribes celebrated the sesquicentennial history of their reservation with a weekend-long event that included cultural activities and a parade. Speakers at the event stressed the important role that Irataba's strong leadership played in establishing and preserving the reservation, and the continuing need for Native leaders to protect native language and culture. Tribal chairman Dennis Patch commented: "Some people would think we're lucky, as we have this river and 220,000 acre feet of water ... But we have had great leaders, like Chief Irataba. He made sure the Mohaves stayed on land they had lived on since time immemorial."[2] Former CRIT Museum Director Dr. Michael Tsosie stated, "Irataba understood the Mohave people would need to keep fighting to keep what they had." He noted that the Colorado River Indian Reservation "is unique in American history in that they have not lost any land".[2]

References edit

Notes edit

- ^ Both the spelling "Mohave" and "Mojave" are correct variants of the English word corresponding to the Mohave word pipa aha macave "People who live by the side of the water". According to some sources (e.g. "The Colorado River Indian Tribes (C.R.I.T.) Reservation and Extension Programs" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2015.) the spelling "Mohave" is preferred by the Colorado River tribe of Mohave which Irataba founded.

- ^ Woodward and Ricky state that this encounter was several years earlier in 1849,[26][5] but this appears to be a result of confusion over the date of the expedition along the Colorado River led by Whipple and Ives. Whipple himself gives the date of the encounter as February 23, 1854, and there is no question that the Whipple Expedition was in 1853 to 1854,[27][28] not 1849.

- ^ Tensions between Mormons and American emigrants reached their peak during 1857–58, with several hostile encounters collectively known as the Mormon War.[39]

- ^ Hunter estimates there were two hundred settlers and four hundred head of cattle, while Baley puts the number at about 100 settlers and 500 head of cattle, as reported by party member John Udell.[54]

- ^ Prior to his trip to Washington in 1863, Irataba had visited Los Angeles, first in 1860, and again in 1861.[91]

- ^ The canal was completed a few months after Irataba's death in 1874.[108]

- ^ An 1867 description indicates that Irataba's hair had remained dark, but due to an old injury he walked with a cane.[125]

- ^ Several contemporary newspapers including The Omaha Daily Bee and The Prescott Miner claim that the Mohave were so committed to Irataba's cremation ritual that they burned their entire village, slaughtered the horses, and fasted for a prolonged period.[131][130][132]

Citations edit

- ^ a b Sherer 1966, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c Gutekunst 2015.

- ^ Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image), (1857)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. x: Yarate:va, Sherer 1966, p. 6: origin and variations of Irataba's name.

- ^ a b c d Ricky 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Kroeber 1925, pp. 725–727.

- ^ Moratto 2014, p. 347.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 6, 29–30.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Stewart 1971, pp. 431–434.

- ^ a b Kroeber 1965, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Johansen & Pritzker 2007, p. 1019: the kwanami were a Mohave warrior society; Sherer 1966, p. 30: Irataba was a kwanami, which means brave or fearless; Fathauer 1954: the role of kwanami in Mohave warfare.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 25.

- ^ McGinty 2005, p. 176.

- ^ a b The Daily Democrat 1891.

- ^ a b Devereux 1951.

- ^ Hinton 1984, p. 281.

- ^ Ives 1861, p. 69.

- ^ Evans 1869, p. 143.

- ^ a b Mifflin 2009, p. 178.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973.

- ^ Sherer 1966.

- ^ Braatz 2003, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Mifflin 2009, pp. 104–107: Olive was released to Henry Grinnell; Putzi 2004, p. 177: Olive and Mary Ann taken captive.

- ^ Whipple & Ives 1856, p. 112.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 54.

- ^ Conrad 1969, p. 147.

- ^ Whipple & Ives 1856, pp. 112–128.

- ^ Whipple & Ives 1856, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b Whipple & Ives 1856, p. 114.

- ^ Whipple & Ives 1856, p. 116.

- ^ Whipple & Ives 1856, pp. 119–128.

- ^ Elsasser 1977, p. 62.

- ^ Mifflin 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Ives 1861, pp. 69–71, 76.

- ^ Miller 1972, pp. 178–179, 182.

- ^ Mifflin 2009, p. 175.

- ^ a b Stewart 1969, p. 230.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 4, 14, 28, 131–132.

- ^ Ives 1861, pp. 77, 85, 92.

- ^ Ives 1861, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Ives 1861, pp. 79–83.

- ^ Ives 1861, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Zappia 2014, pp. 121, 138.

- ^ Ives 1861, pp. 94–97, 102.

- ^ a b Miller 1972, p. 188.

- ^ Kroeber & Fontana 1986.

- ^ a b Kroeber 1965, p. 175.

- ^ Thrapp 1991, p. 76.

- ^ a b Hunter 1979, p. 139.

- ^ Utley 1981, p. 164.

- ^ Sherer 1994, p. 69.

- ^ Hunter 1979, p. 138.

- ^ Hunter 1979; Baley 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Kroeber 1965, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Sherer 1994, pp. 82–86, 95.

- ^ Baley 2002, pp. 2–3, 5, 15, 24, 28–40, 61–62, 67–72: emigrant train and attack; Zappia 2014, p. 129: seventeen Mohave warriors.

- ^ Sherer 1994, p. 82.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 14.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, pp. 54–54.

- ^ a b c Woodward 1953, p. 58.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 63: Irataba attempted to arrange a peaceful meeting; Woodward 1953, p. 58: the Mohave attacked and repelled the force.

- ^ Sherer 1966, p. 3: Homoseh quahote attended the meeting; Woodward 1953, p. 59: Irataba and Cairook.

- ^ a b Hunter 1979, p. 150.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, pp. 25, 66.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 59.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 24: soldiers remained to build a fort; Sherer 1965, p. 73: the fort was initially called Fort Colorado.

- ^ Mifflin 2009, p. 177.

- ^ a b Woodward 1953, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 27.

- ^ Sherer 1994, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 60.

- ^ Scrivner 1970, p. 134: becoming leader; Sherer 1966, pp. 2, 5–6: attaining Aha macave yaltanack.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Sherer 1966, p. 2.

- ^ Devereux 1951, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 9, 30.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 1–14.

- ^ "Santa Fe Weekly Gazette". September 17, 1853.

- ^ Paher, Stanley (1979). Colorado River Ghost Towns. Las Vegas, Nevada: Nevada Publications.

- ^ Casebier, Dennis (1970). Camp El Dorado, Arizona Territory. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Historical Foundation. p. 19.

- ^ Webb, George (1974). "The Mines in Northwestern Arizona in 1864, a Report by Benjamin Silliman, Jr". Arizona and the West. 16 (3): 249 fn 4.

- ^ Spude, Robert (2009). "Who were the First Hassayampers". Territorial Times. II (2): 3.

- ^ Hanchett 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Woodward 1953, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Shumway, Vredenburgh & Hartill 1980, p. 76.

- ^ Webb & Silliman 1974, p. 270.

- ^ Webb, George (1974). ""The Mines in Northwestern Arizona 1864, the Report by Benjamin Silliman, Jr". Arizona and the West. 16 (3): 248–250.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 63.

- ^ Scrivner 1970, p. 134.

- ^ a b Woodward 1953, pp. 61–62.

- ^ O'Brien 2006, p. 249.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 53.

- ^ a b Woodward 1953, pp. 62–63.

- ^ The New York Times 1864.

- ^ a b Mifflin 2009, p. 180.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 62.

- ^ Ricky 1999, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Carlson 1886, p. 492.

- ^ Woodward 1953, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Ricky 1999, p. 102.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 66.

- ^ Knack 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Caylor 2000, p. 196.

- ^ a b Sherer 1966, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c d Caylor 2000.

- ^ Griffin-Pierce 2000, p. 246: relocating to the Colorado River Valley; Caylor 2000, p. 196: a fifth of the entire Mohave Nation; Sherer 1966, pp. 6–8: 800 Mohave.

- ^ a b Kappler 1904.

- ^ Caylor 2000, p. 197: soil was too alkaline

- ^ a b Swanton 1952, p. 357.

- ^ Sherer 1966, pp. 4–5, 8–9.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 31.

- ^ Andrews 1870, p. 647.

- ^ Gentile 1870.

- ^ Kroeber 1965, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Woodward 1953, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Knack 2004, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Daily Alta California 1865, p. 1.

- ^ McNichols 1944, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Kroeber & Kroeber 1973, p. 40.

- ^ a b Kroeber 1965, p. 179.

- ^ a b Woodward 1953, p. 67.

- ^ Evans 1870, p. 41.

- ^ Farish 1918.

- ^ Braatz 2003, pp. 112, 135.

- ^ Wilson 2007, p. 130.

- ^ Braatz 2003, p. 135.

- ^ a b The Omaha Daily Bee 1874, p. 2.

- ^ Arizona Weekly Miner 1874, p. 1.

- ^ Woodward 1953, p. 68.

- ^ Sherer 1966, p. 13.

- ^ Hinton 1979.

- ^ Kulp 1974, p. 3.

- ^ Cook 1985, p. B-2.

- ^ The Yuma Daily Sun 1975, p. 3.

- ^ Bureau of Land Management.

Bibliography edit

- "Irataba". Arizona Weekly Miner. Vol. XI, no. 23. June 5, 1874. p. 1 – via Chronicling America.

- Andrews, George L. (1870). "Accompanying Papers, No. 38". In United States Department of the Interior (ed.). Executive Documents Printed by Order of the House of Representatives During the Second Session of the Forty-First Congress, 1869–'70. Vol. 3. Government Printing Office. pp. 646–648. OCLC 30751534.

- Baley, Charles W. (2002). Disaster at the Colorado: Beale's Wagon Road and the First Emigrant Party. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-87421-437-6.

Free Download Full Text

- Braatz, Timothy (2003). Surviving Conquest. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2242-7.

- Bureau of Land Management. "Ireteba Peaks Wilderness". United States Government. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Carlson, Edward (1886). "The Martial Experiences of the California Volunteers". The Overland Monthly. Second series. 7 (41): 480–496.

- Caylor, Ann (2000). "A Promise Long Deferred: Federal Reclamation on the Colorado River Indian Reservation". Pacific Historical Review. 69 (2): 193–215. doi:10.2307/3641438. JSTOR 3641438.

- Conrad, David E. (1969). "The Whipple Expedition in Arizona 1853–1854". Arizona and the West. 11 (2): 147–178.

- Cook, Fred (September 25, 1985). "Celebration planned by Indian tribes for re-opening of museum". The San Bernardino County Sun. p. B-2 – via Newspapers.com.(subscription required)

- "Latest from Irataba's Land". Daily Alta California. Vol. 17, no. 5707. October 22, 1865. p. 1.

- Devereux, George (1951). "Mohave Chieftainship in Action: A Narrative of the First Contacts of the Mohave Indians with the United States". Plateau. 23 (3): 33–43.

- Elsasser, Albert B. (1977). "Mohave Indian Images and the Artist Maynard Dixon". The Journal of California Anthropology. 4 (1): 60–79.

- Evans, Albert S. (1869). "A Cloud-Burst on the Desert". The Overland Monthly. 3 (2): 138–143.

- Evans, Albert S. (July 1870). "Lo-land Adventure". The Galaxy. 10.

- Fathauer, George H. (1954). "The Structure and Causation of Mohave Warfare". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 10 (1): 97–118. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.10.1.3629078. S2CID 155976554.

- Farish, T. E. (1918). "XVI". History of Arizona (Vol. VIII). Filmer brothers electrotype Company.

- Gentile, Carlo (1870). "Ah-oochy Kah-mah & his friend Irateba Two Tonto Apache girls, civilized & christians, good girls; Coyotero Apache woman, sold by her lord & master for 40 yards Manta at Camp Grant; Joséa, Pimo [i.e., Pima] Fat Boy, front view". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy (2000). Native Peoples of the Southwest. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-1908-1.

- Gutekunst, John (March 3, 2015). "CRIT celebrates 150th anniversary of reservation". Parker Pioneer. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- Hanchett, Leland J. (1998). Catch the Stage to Phoenix. Pine Rim Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9637785-6-7.

- Hinton, Leanne (1979). "Irataba's gift: a closer look at the ṣ > s > θ sound shift in Mohave and Northern Pai". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Papers in Linguistics. 1 (1): 3–39.

- Hinton, Leanne (1984). Spirit Mountain: An Anthology of Yuman Story and Song. Sun Tracks and University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-0843-3.

- Hunter, L. G. (1979). "The Mojave Expedition of 1858–59". Arizona and the West. 21 (2): 137–156.

- "Indian Marriages". The Daily Democrat. June 3, 1891. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ives, Joseph C. (1861). "Part I: General Report". In United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers (ed.). Report upon the Colorado River of the West : Explored in 1857 and 1858 by Joseph C. Ives. Government Printing Office. OCLC 3095199. 36th Congress, 1st Session Senate executive document, unnumbered.

- Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M., eds. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Indian History (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7.

- Knack, Martha C. (2004). Boundaries Between: The Southern Paiutes, 1775–1995. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7818-9.

- Kappler, Charles J. (1904). "PART III.—Executive Orders Relating to Indian Reserves". Washington: Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on December 9, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California. Courier. ISBN 978-0-486-23368-0.

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis; Kroeber, Clifton B. (1973). A Mohave War Reminiscence, 1854–1880. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-28163-6.

- Kroeber, Clifton B. (June 15, 1965). "The Mohave as Nationalist, 1859–1874". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 109 (3): 173–180.

- Kroeber, C. B.; Fontana, B. L. (1986). Massacre on the Gila. An account of the last major battle between American Indians, with reflections on the origin of war. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-0969-0.

- Kulp, Neil (April 3, 1974). "Parker's Irataba receives $5000 plus bonus of meeting Franco Harris". The Yuma Daily Sun. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.(subscription required)

- McGinty, B. (2005). The Oatman Massacre: A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8024-3.

- McNichols, Charles Longstreth (1944). Crazy Weather. Macmillan. OCLC 1267884.

- Mifflin, Margot (2009). The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1148-3.

- Miller, David H. (1972). "The Ives Expedition Revisited: Overland into Grand Canyon". The Journal of Arizona History. 13 (3): 177–196.

- Moratto, Michael J. (2014). California Archaeology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-7735-6.

- "Arrival of the Indian Warrior, Irataba". The New York Times. February 7, 1864. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- O'Brien, Anne Hughes (2006). Traveling Indian Arizona. Big Earth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56579-518-1.

- "Aboriginalities" (PDF). The Omaha Daily Bee. Vol. 4, no. 12. July 2, 1874. p. 2 – via Chronicling America.

- Putzi, Jennifer (2004). "Capturing Identity in Ink: The Captivities of Olive Oatman". Western American Literature. 39 (2): 176–199. doi:10.1353/wal.2004.0002. S2CID 165937685.

- Ricky, Donald B. (1999). Indians of Arizona: Past and Present. Native American Books Distributor. ISBN 978-0-403-09863-7.

- Scrivner, Fulsom Charles (1970). Mohave People. The Naylor Company. ISBN 978-0-8111-0335-0.

- Sherer, Lorraine M. (1965). The Clan System of the Fort Mojave Indians. Historical Society of Southern California. OCLC 3512671.

- Sherer, Lorraine M. (March 1966). "Great Chieftains of the Mojave Indians". Southern California Quarterly. 48 (1): 1–35. doi:10.2307/41169985. JSTOR 41169985.

- Sherer, Lorraine M. (1994). Vane, Sylvia Brakke; Bean, Lowell John (eds.). Bitterness Road: The Mojave: 1604 to 1860. Ballena Press. ISBN 978-0-87919-128-3.

- Shumway, G. L.; Vredenburgh, L. M.; Hartill, R. D. (1980). Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining in the California Desert Conservation Area (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2015.

- Stewart, Kenneth M. (1971). "Mohave Warfare". In Heizer, Robert Fleming; Whipple, Mary Anne (eds.). The California Indians: A Source Book. University of California Press. pp. 431–444. ISBN 978-0-520-02031-3.

- Stewart, Kenneth M. (1969). "A Brief History of the Mohave Indians since 1850". Kiva. 34 (4): 219–236. doi:10.1080/00231940.1969.11760552.

- Swanton, John Reed (1952). The Indian Tribes of North America. Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4.

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: A-F. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9418-9.

- Utley, Robert Marshall (1981). Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848–1865. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9550-6.

- Webb, G. E.; Silliman, B. (1974). "The Mines in Northwestern Arizona in 1864: A Report by Benjamin Silliman, Jr". Arizona and the West. 16 (3): 247–270.

- Whipple, Amiel Weeks; Ives, Joseph C. (1856). "Part I: Itinerary". In United States Department of War (ed.). Reports of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Vol. 3. A.O.P. Nicholson. 33rd Congress, 2nd Session House executive document number 91.

- Wilson, R. Michael (2007). Massacre at Wickenburg: Arizona's Greatest Mystery. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-4453-4.

- Woodward, Arthur (January 1953). "Irataba: Chief of the Mohave". Plateau. 25 (3): 53–68.

- "Parker Troth". The Yuma Daily Sun. January 21, 1975. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.(subscription required)

- Zappia, Natale A. (2014). Traders and Raiders: The Indigenous World of the Colorado Basin, 1540–1859. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-1585-1.

Further reading edit

- Curry, John Penn (1865). "An Indian Chief's Opinion of Americans". Gazlay's Pacific Monthly. 1 (1): 360.

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1902). "Preliminary Sketch of the Mohave Indians". American Anthropologist. New Series. 4 (2): 276–285. doi:10.1525/aa.1902.4.2.02a00060. JSTOR 659222.

- Wilson, James (2000). The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3680-0.

External links edit

- Pipa Aha Macav – "The People by the River": The Official Website of the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe

- InterTribal Council of Arizona – Colorado River Indian Tribes

- Tribal website – Colorado River Indian Tribes