Summary

Galileo Galilei was one of four Archimede-class submarines built for the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy) during the early 1930s. She was named after Galileo Galilei, an Italian astronomer and engineer.

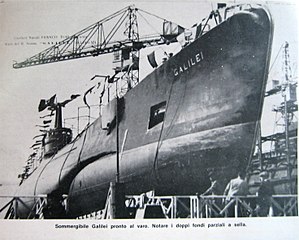

Launch of Galileo Galilei in Taranto, 1934

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Galileo Galilei |

| Namesake | Galileo Galilei |

| Builder | Tosi, Taranto |

| Laid down | 15 October 1931 |

| Launched | 19 March 1934 |

| Commissioned | 16 October 1934 |

| Captured | by the Royal Navy, 19 June 1940 |

| Name | X-2, later P771 |

| Acquired | June 1940 |

| Commissioned | June 1942 |

| Fate | Scrapped, January 1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Archimede-class submarine |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 70.5 m (231 ft 4 in) |

| Beam | 6.87 m (22 ft 6 in) |

| Draft | 4.12 m (13 ft 6 in) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Range |

|

| Armament |

|

Design and description edit

The ships were designed by the firm Cavallini and were an enlarged version of the preceding Settembrini-class submarine. Among the changes were the introduction of a partially double hulled design, rearrangement of the ballast tanks, increases in fuel capacity and range, and a strengthening of the armament. The number of torpedoes was increased from 12 on the Settembrini class to 16.[1][2]

They displaced 980 metric tons (960 long tons) surfaced and 1,260 metric tons (1,240 long tons) submerged. The submarines were 70.51 meters (231 ft 4 in) long, had a beam of 6.87 meters (22 ft 6 in) and a draft of 4.12 meters (13 ft 6 in).[2]

For surface running, the boats were powered by two 1,500-brake-horsepower (1,119 kW) diesel engines, each driving one propeller shaft. When submerged each propeller was driven by a 700-horsepower (522 kW) electric motor. They could reach 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) on the surface and 7.7 knots (14.3 km/h; 8.9 mph) underwater. On the surface, the Archimede class had a range of 10,300 nautical miles (19,100 km; 11,900 mi) at 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), submerged, they had a range of 105 nmi (194 km; 121 mi) at 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph).[2]

The boats were armed with eight internal 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes, four in the bow and four in the stern. They were also armed with two 100 mm (4 in) deck gun for combat on the surface. The light anti-aircraft armament consisted of two single 13.2 mm (0.52 in) machine guns.[2]

Construction and career edit

In Regia Marina edit

Galileo Galilei was built at Tosi shipyard at Taranto. She was launched on 19 March 1934 and commissioned on 16 October that year.[3] After delivery, Galileo Galilei together with other submarines of Archimede-class was assigned to 12th Squadron of the III Flotilla, later to become 41st and then 44th Submarine Squadron of the VII Submarine Group, based at Taranto. After a period of intensive training and short cruises, the Squadron was sent for training to Tobruk.

In 1937, along with many other submarines of the Royal Italian Navy (Regia Marina), Galileo Galilei secretly participated in the Spanish Civil War, conducting several missions without achieving any success. Following the Iride-HMS Havock incident, in September 1937 the Nyon Conference was called by France and Great Britain to address the "underwater piracy" conducted against merchant traffic in the Mediterranean. On 14 September, an agreement was signed establishing British and French patrol zones around Spain (with a total of 60 destroyers and airforce employed) to counteract aggressive behavior by submarines. Italy was not directly accused, but had to comply with the agreement and suspend the underwater operations.

Under pressure from Franco's regime, Italy decided to transfer 4 more submarines (in addition to Archimede and Evangelista Torricelli already being operated by the Falangists) to the Spanish Legion (Legión Española or Tercio de Extranjeros). Galileo Galilei was one of the four boats chosen for the transfer. On 26 September 1937 Galileo Galilei arrived at Soller on Mallorca. She was placed under the direct command of Spanish admiral Francisco Moreno, was renamed General Mola II and assigned pennant number L1. However, Galileo Galilei retained her commander (captain Mario Ricci), senior officers and Italian crew, but they had to wear Spanish uniforms and insignia.

The other three Italian submarines transferred to Tercio were Onice (Aguilar Tablada), Iride (Gonzalez Lopez) and Galileo Ferraris (General Sanjurjo II). All four were based at Soller. Galileo Galilei conducted several patrols without any success. In February 1938 she returned home, as Italy withdrew their submarines from Spanish service due to international pressure. Upon her return, Galileo Galilei was temporarily assigned to the 44th Squadron of the VII Submarine Group based at Taranto, together with Galileo Ferraris, and the more modern Archimede, Brin, Guglielmotti, Torricelli and Galvani. During 1939 Galileo Galilei and Galileo Ferraris were moved to a different location and the 44th Squadron was renamed to 41st Squadron.

In March 1940, Galileo Galilei together with Galileo Ferraris were transferred to Massawa in Eritrea where she formed 81st Squadron of VIII Submarine Group.

At the time of Italy's entrance into World War II Galileo Galilei was stationed at the Italian base of Massawa on the Red Sea being part of the Italian Red Sea Flotilla. On 10 June 1940 the submarine, under the command of captain Corrado Nardi, was ordered to proceed to her area of operation near Aden where she arrived on 12 June.[4] In the early morning of 16 June, while submerged, she intercepted Norwegian tanker James Stove, about 12 miles south of Aden. After surfacing and ordering the crew to leave the ship, Galileo Galilei fired three torpedoes that set the ship on fire and sank the tanker.[4] It is likely, the explosions were heard in Aden and the smoke column rising from the burning tanker was also observed, but no British ships or planes appeared and the submarine continued her mission unmolested until the afternoon of 18 June when a Yugoslavian steamer Drava was spotted. Galileo Galilei fired a shot across the bow ordering the ship to stop, but after seeing the ship was under a neutral flag, the steamer was allowed to leave. However, the gunfire was heard by the anti-submarine warfare trawler HMS Moonstone who fired a warning signal. At around 16:30, while the submarine was still on the surface, she was attacked by an enemy plane. Galileo Galilei was forced to submerge but remained on station considering a rather weak response to her sighting. When the darkness fell, the boat resurfaced to recharge the batteries, but it was discovered by the British ship forcing the submarine to crash dive and go through a brief but intense depth-charge attack which did not cause any damage. In the morning of 19 June, while Galileo Galilei was laying immobile on seabed, the first mild symptoms of methylchloride poisoning appeared in some crew members.[4] Meanwhile, the submarine had been detected by HMS Moonstone who launched another depth-charge attack. Captain Nardi ordered the submarine to the periscope depth, examined his adversary and noted their single 4-inch gun and a pair of machine guns. Considering possible effects of methylchloride poisoning if the submarine continued staying submerged, and the modesty of the trawler's armament, he decided to face HMS Moonstone on the surface with his two 100 mm guns and two machine guns. As the fight began, the bow gun's sighting mechanism on the Galileo Galilei failed, greatly affecting the accuracy of shooting.

Moonstone also moved too fast for the submarine's crew to aim their guns effectively. After about ten minutes Galileo Galilei was hit for the first time, wounding commander Nardi and killing several people around him.[5] Shortly thereafter, the bow gun was hit killing the gun crew including the second in command. The gun continued shooting, however, under command of Ensign Mazzucchi. The aft gun soon jammed, and then another salvo from Moonstone killed all those on the conning tower including Nardi. The bow gun continued shooting until HMS Kandahar arrived at the scene and Mazucchi, as the most senior on board the submarine, ordered Galileo Galilei to stop shooting and surrender.[5] The submarine had lost 16 men: commander Nardi, four other officers, seven NCOs and four sailors.[6] The submarine was then towed into Aden by Kandahar.

Though the British side claimed that the submarine's codebooks and operational documents were captured intact by the Royal Navy, and revealed the exact position of other Italian naval units, Italian survivors (including Ensign Mazzucchi) reported that every document was destroyed before surrender, and that no written operational orders were issued to Italian units, only an oral briefing between captains and the submarine command in Massawa before every mission.[7] The claim was reported only to cover the British intelligence activities in Italian East Africa.[7]

edit

After her capture, Galileo Galilei was berthed at Port Said and served as a generating station to charge the batteries of British submarines.[8] She was commissioned into the Royal Navy in June 1942 as HMS X2 (later changed to P 711), and was operated as a training boat in the East. She was scrapped on 1 January 1946.

| Date | Ship | Flag | Tonnage | Ship Type | Cargo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 June 1940 | James Stove | 8,215 GRT | Tanker | Aviation Fuel | |

| Total: | 8,215 GRT | ||||

See also edit

- HMS Graph – another captured submarine (formerly the U-570) commissioned into the Royal Navy

- HMS Seal – Royal Navy submarine, captured and taken into service by the Germans as UB.

- Perla – captured Regia Marina submarine commissioned into the Royal Navy (P-712), and then into Hellenic Navy

Notes edit

Bibliography edit

- Bagnasco, Erminio (1977). Submarines of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-962-6.

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-544-8.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Frank, Willard C. Jr. (1989). "Question 12/88". Warship International. XXVI (1): 95–97. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Miller, David (2002). Illustrated Directory of Submarines. Zenith. ISBN 978-0-7603-1345-9.

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn, Captain F.C. (R.N.) & Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2009) [1st. pub. HMSO:1954]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume I: The Early Successes Against Italy, to May 1941. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-065-8.

External links edit

- Galileo Galilei (1934) Marina Militare website